September 2015

John Vincent Bellezza

Flight of the Khyung surveys the ancient rock art of Spiti situated on the western rim of the Tibetan plateau! The last four newsletters have been devoted to the early cultural history and archaeology of Spiti and this one follows suit with more information and wonderful images. Readers are encouraged to consult those earlier issues for background information. Spiti will remain the focus of the next issues of Flight of the Khyung as well.

The extensive treatment of the rock carvings (petroglyphs) and rock paintings (pictographs) of Spiti that follows is the first of a three-part article. The other two parts of this work will appear in the October and November newsletters.

As explained in the July newsletter, no less than 6000 individual rock art compositions were recently documented in Spiti. In the July and August newsletters around 100 images of this rock art were published. In this month’s newsletter there are an additional 186 images to be followed by around 200 more images in the October and November newsletters. In total, approximately 450 different photographs of Spitian rock art are to be published in the July to November issues of Flight of the Khyung.

A Survey of the Rock Art of Spiti – Part 1

Introduction

This comprehensive survey of rock art in Spiti is the first of its kind. The petroglyphs and pictographs selected for publication in this article belong to what might be called the standard or indigenous art of the region, compositions, subjects and motifs that recur in most places and phases of Spitian rock art. This body of rock art is remarkable for its thematic coherence, the production of a people sharing a common cultural idiom of great persistence. For information on the cultural and historical dimensions of the Spiti rock art tradition, see the July and August 2015 Flight of the Khyung.

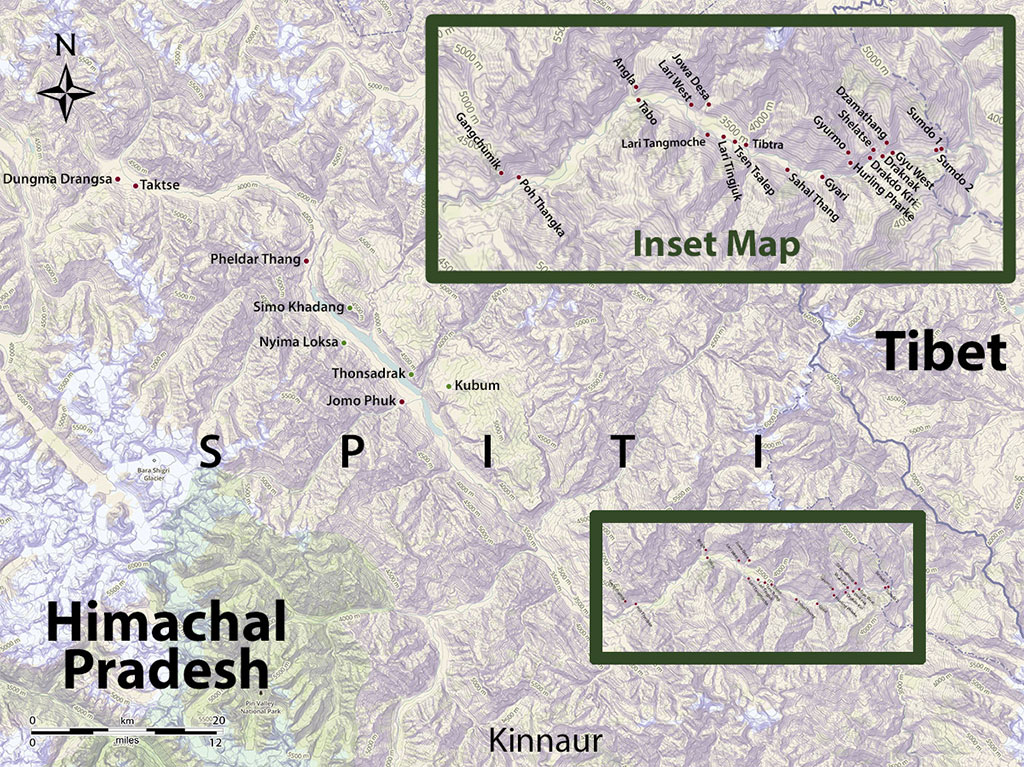

This article is organized on a site-by-site basis, beginning in lower (southeast) Spiti and continuing up towards the northern extension of the region. In this first part of the article the following sites are treated (for a complete list of rock art sites in Spiti, see the July 2015 Flight of the Khyung):

- Sumdo 1 (Sum-mdo; el. 3070 m)

- Sumdo 2 (el. 3060 m)

- Dzamathang (rDza-ma-thang; el. 3160–3190 m)

- Shelatse (Shel-la-rtse; el. 3260–3280m)

- Hurling Pharke (Hur-gling phar-ke; el. 3210 m)

- Gyurmo (Gyur-mo; el. 3350–3390 m)

- Gyu West (rGyu; el. 3090–3130 m)

- Draknak (Brag-nag; el. 3155 m)

- Drakdo Kiri (Brag-rdo ki-ri; el. 3180 m)

- Gyari (rGya-ri; el. 3225–3250 m)

- Sahal Thang (Sa-skal thang; 3190–3215 m)

- Tibtra (3200 m)

- Tsen Tsalep (rTsan-rtsa-leb; el. 3210–3230 m)

- Lari Tingjuk (La-ri Ting-mjug; 3240–3260 m)

The rock art of each site is organized according to general themes in the following order:

- Zoomorphic portraits (individual or collective depiction of animals and supermundane entities in human form).

- Anthropomorphic portraits (individual or collective depiction of human beings and supermundane entities in animal form).

- Hunting scenes and other interactions between anthropomorphs and zoomorphs (depiction of humans and animals in concert).

- Geometric subjects (rectilinear and curvilinear designs of varying complexity), with and without anthropomorphs and zoomorphs.

- Apparent shrines and other types of ritual structures (an enigmatic class of rock art).

- Symbolic subjects (signs, emblems and icons that appear to have been invested with prescribed forms of abstract meaning).

In its three parts, this article presents approximately 6% of the 6000 pictures of rock art taken on this year’s Spiti Antiquities Expedition. The objective of publishing these images is to furnish a comprehensive pictorial survey of Spitian rock art. To accomplish this goal, a diverse selection of rock art on a site-by-site basis is showcased in an attempt to reflect the full range of contents. The contents of rock art can be delineated as follows:

- Theme (analogous scenes, topics and ideas articulated in a body of compositions)

- Composition (one or more petroglyph or pictograph created as an integral work)

- Subject (individual figures or symbols making up a composition)

- Motif (prominent element used in the depiction of a subject)

- Style (mode of artistic expression)

- Technique (physical execution and tools used in production)

This survey does not necessarily reflect the frequency of specific aspects of the contents of Spitian rock art. For example, the number of swastikas and blue sheep shown is not proportional to their numerical representation. That is because furnishing numerous iterations of rock art with limited stylistic variation would not add much to the comprehensiveness of this survey nor greatly enhance an appreciation of the rock art tableau.

Although a substantial array of rock art is featured here, it represents a small fraction of the complete corpus. Thus this survey cannot capture the full richness of artistic endeavor in stone, a tradition practiced in Spiti by untold people for no less than 1500 years. The skill and inventiveness of many individual creators of rock art characterized by numerous permutations in the standard contents as well as by idiosyncratic representations have per force been omitted from this survey.

The compilation of an exhaustive catalog of rock art in Spiti would have its own special scientific value, such as facilitating statistical forms of analysis and comparative exercises not possible in an article of this scope. This is a task however for a future effort.

Chronological terminology used in this article (for an explanation, see July 2015 Flight of the Khyung) and salient features of each phase of rock art are as follows:

I. Prehistoric epoch

- Early Iron Age (circa 900–500 BCE): Anthropomorphs with angular appendages and prominent displays of male genitalia, with and without wild ungulates. Deeply carved; very heavily re-patinated petroglyphs restricted in technique and style.*

- Iron Age (circa 500–100 BCE): Tigers and horned eagles exhibiting Upper Tibetan and Ladakhi influences; anthropomorphs with angular appendages and male genitalia, with and without wild ungulates; spirals and other geometrics. Deeply carved or finely engraved; heavily to moderately re-patinated petroglyphs somewhat restricted in technique and style.

- Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 630 CE): Anthropomorphs with angular and rounded appendages; archers on foot and horseback hunting wild ungulates; complex curvilinear and rectilinear designs; elementary tiered shrines. Less deeply carved; moderately re-patinated petroglyphs of diverse styles and techniques. Pictographs of analogous styles and themes.

II. Historic epoch

- Early Historic period (630–1000 CE): Portraits of horse riders and standing anthropomorphs in less iconical forms; complex tiered shrines (stupas); conjoined sun and moon; geometrics based on earlier phases of rock art. Most carvings shallow; modeling of figures stiff. Pictographs of analogous styles and themes.

- Vestigial period (1000–1300 CE): Buddhist artistic influences and themes as well as art imitative of earlier phases.

- Later Historic period (post-1300 CE): Copycat art contrived in style and presentation.

The label “Early Iron Age” and the chronology assigned to it in this work reflect broader Eurasian archaeological usage. At this juncture, it has not been determined what kind of economy and technological development Spiti had in the first half of the first millennium BCE.

In this survey of Spiti rock art there are certain subjects, motifs and styles that recall the rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh. These affinities may not be as compelling as those studied in last month’s newsletter but they are still noteworthy. Similarities between the rock art of Spiti and Ladakh and Spiti and Upper Tibet potentially have three major causes:

- The transfer of artistic forms to Spiti (mimesis effected through ideology, religious values, less formalized social responses, economic exigencies, political pressure and other agents).

- Pre-existing cultural and/or ethnic ties between Spiti and its plateau neighbors giving rise to the development of parallel art forms.

- Purely coincidental artistic resemblances without inter-regional and inter-cultural factors involved.

Note: The primary objective in the presentation of images is clarity of form. This sometimes required digitally enhancing images in such away that exaggerates the color of the background surface.

The rock art sites of Spiti: red dot denotes petroglyphs, green dot denotes pictographs. Map by Brian Sebastian and John Vincent Bellezza. Click to enlarge.

Sumdo 1

Fig. 1.1. A blue sheep portrayed as if running (head facing right). Protohistoric period.

This is one of three wild caprids carved on a southwest-facing rock face suspended above the main road that runs through Spiti. As explained in the July 2015 Flight of the Khyung, the blue sheep is the most common zoomorphic depiction in the rock art of Spiti. This rendering of the animal with its rather linear form, hooked tail, and short curving horns extending on both sides of its head captures salient features of much blue sheep rock art in Spiti. Individual or collective portraits of wild ungulates were potentially created for a variety of purposes and with manifold meanings (for a review of these factors, see Bellezza 2008: 171–175).

Sumdo 2

Fig. 2.1 Ibex being attacked from the rear by a carnivore. Protohistoric period.

This composition features a carnivore (wolf or feline) springing up at an ibex (identified by the long horns curving over the body in the same direction). Predator attack scenes are fairly common in the rock art of Spiti. Nevertheless, the location of the great boulder at Sumdo 2 on the road to Guge in Upper Tibet, the fine engraving technique used to create the composition, and the contents of rock art at the site more generally suggest that Upper Tibetan influences were behind the creation of this predator attack scene. This composition was possibly inspired by martial tradition, which appears to be represented at the site by a group of tiger petroglyphs (see last month’s newsletter). There are several other ibex carvings at Sumdo 2, the second most common animal portrayed in the rock art of Spiti.*

On the geographic range of blue sheep and ibex in Tibet, see Schaller 1998, pp. 102, 103; on the distribution of wild yaks, see ibid., pp. 128–136.

Dzamathang

Fig. 3.1. An ibex and what appears to be a blue sheep. Protohistoric period. This composition is located on the side of a boulder, the top of which has four tiered shrines and other carvings (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 67).

Fig. 3.2. Wild caprid (17 cm long). Protohistoric period. On this same boulder are three horsemen (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung, figs. 26–28).

Fig. 3.3. A composition consisting of a number of archers hunting wild ungulates. Early Historic period.

Fig. 3.4. An emblematic anthropomorph (10 cm high). Protohistoric period.

This figure has characteristic traits of anthropomorphic art belonging to the Protohistoric period: round head, arms pointing downward, long, straight body and legs spread apart. On the same boulder is another anthropomorph in an analogous style and a few other figures.

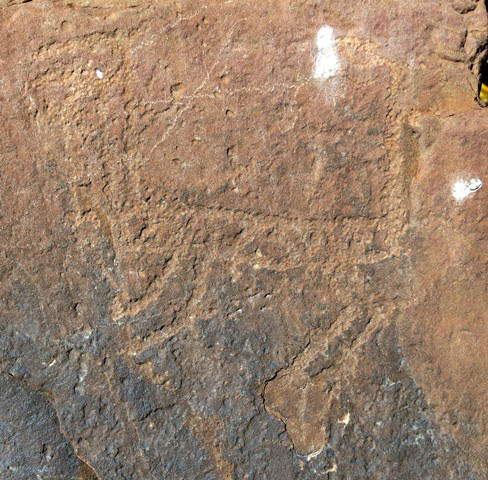

Fig. 3.5. A square subdivided into perhaps eight quarters. Protohistoric period.

On this large boulder are various animal and other petroglyphs.

Shelatse

Fig. 4.1. A portrait of a single blue sheep (67 cm long) occupying nearly the entire side of a boulder. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

This is an unusually large zoomorphic figure, but the style belongs to the standard repertoire of Spiti rock art.

Fig. 4.2. A horizontal face of a boulder with a number of blue sheep and other animals. Protohistoric period.

This is a typical scene of wild caprids in the rock art of Spiti. Due to extreme wear, it could not be confirmed whether anthropomorphs or other figures are present among the animals.

Fig. 4.3. An anthropomorph with arms joined in front, legs spread and relatively large round head. Early Historic period. This figure was partially carved over the petroglyph of a wild caprid.

Several other wild caprids are found on the same boulder. The superimposition of later rock art on older compositions is not as common in Spiti as it is in Upper Tibet. Lower Spiti had an ample supply of boulders for carving, lessening competition for stone canvasses. The smaller number of palimpsests may also be due to the apparent cultural homogeneity and socioeconomic stability of Spiti and to its rapid absorption of Buddhism.

Hurling Pharke

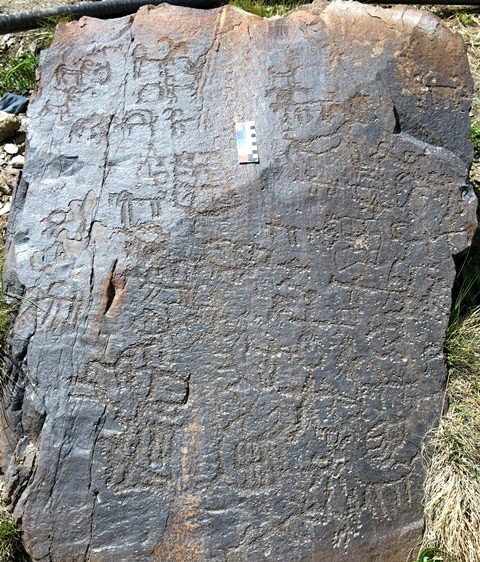

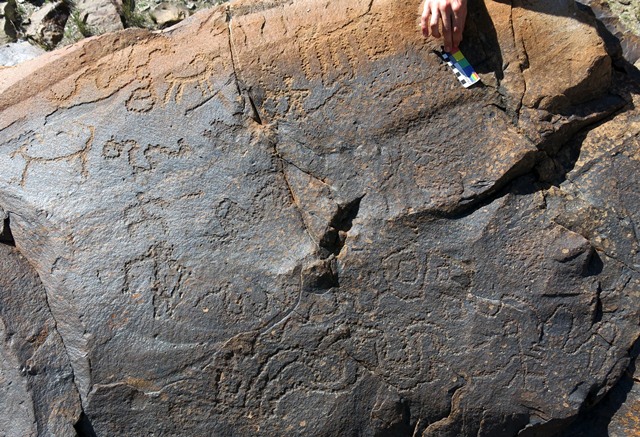

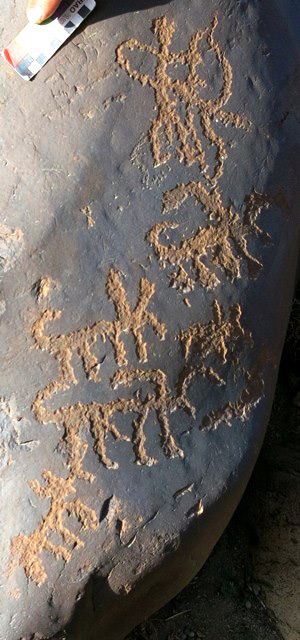

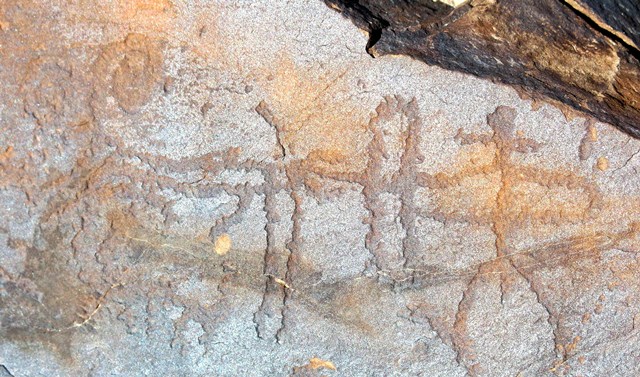

Fig. 5.1. A large southeast-facing panel pullulating with around 50 anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures and a few rectilinear geometrics. The petroglyphs are dominated by wild caprids and they may be the only species of animals depicted on the boulder. There are at least five anthropomorphs on the panel, two of which clearly have bows. In conventional Spitian style, the sundry figures are in very close proximity or actually touching one another. Iron Age.

This is another example of a symphony of figures, interrelated chronologically as well as functionally. Although the hunting of wild caprids appears to be represented, this is not necessarily the dominant theme of this complex of petroglyphs. Cult functions with mythological, ritual or narrative elements can be easily imagined. One wonders if the two geometric subjects on the top half of the boulder might possibly portray pens or traps used to corral wild caprids during the hunt. Of course a number of alternative explanations for these types of petroglyphs can also be considered.

Fig. 5.2. The lower right portion of the boulder in fig. 5.1. Note the three bowmen in the upper middle part of the photograph. They appear to be firing on wild caprids located to the right. Below these hunters there seem to be two other anthropomorphs. Also in this image are opposing caprids creating two square configurations.

Fig. 5.3. A close-up of the uppermost archer in fig. 5.1. This anthropomorph exhibits characteristic features of Spitian rock art including a small, round head, long, straight body and male genitalia.

Gyurmo

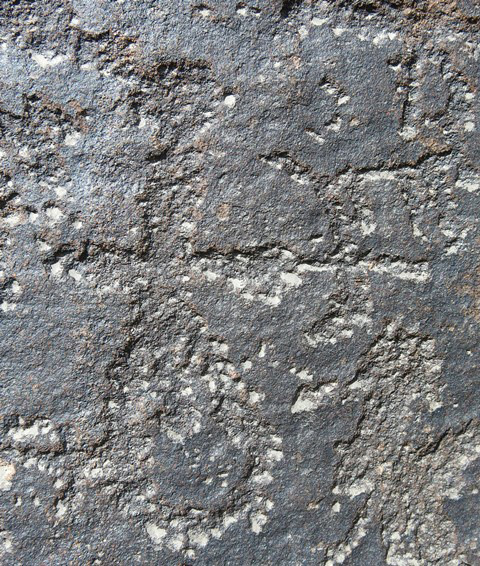

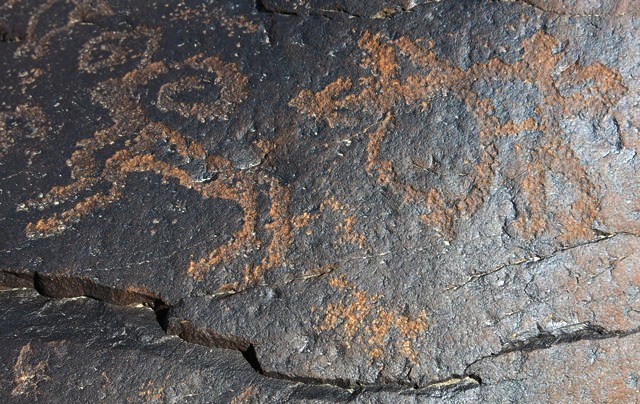

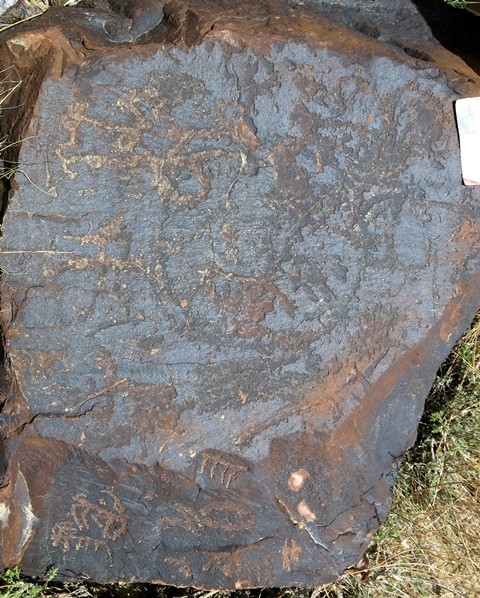

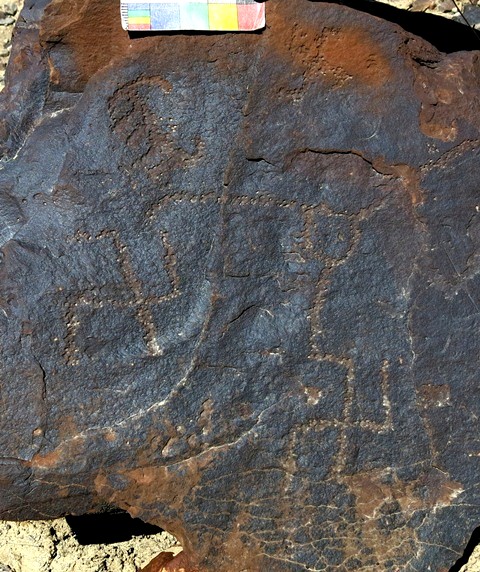

Fig. 6.1. A large west-facing panel (1.1 m x 1 m) of a boulder with more than 90 figures, including anthropomorphs, animals in a variety of aspects, geometrics and swastikas. Iron Age and Protohistoric period.

There are at least one dozen emblematic male figures on this boulder, some of which are brandishing bows and other objects. The majority of wild animals represented are wild caprids, but one wild yak can be recognized (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 33). The heavily re-patinated figures on this stone surface appear to be among the earliest examples of rock art in Spiti and could possibly date to the Early Iron Age. The less re-patinated figures, including animals in a more linear style and anthropomorphs characterized by greater stylistic variability, appear to date to the Protohistoric period.

Fig. 6.2. The upper right portion of the panel in fig. 6.1. The differences in style and physical condition between the Iron Age and Protohistoric period rock art can be clearly be seen in this image. At the bottom center of the photo is a large anthropomorphic figure that was superimposed on earlier carvings.

Some of the differences in coloration and texture of the carvings are due to the geochemical scouring away of the varnish that once covered the upper portion of the stone panel. This has the effect of amplifying the contrast between various figures. Despite different phases of rock art being represented, there is much coherence in subject matter and stylistic modes.

Fig. 6.3. Left side of the same rock face shown in fig. 6.1. Here we see a variety of carvings, all of which put male figures in close proximity to wild ungulates.

Some of these associations are likely to involve hunting or perhaps more accurately, the mytho-ritual basis of the ancient venatic traditions of Spiti.

Fig. 6.4. A close-up of an ibex carving on the same rock face as fig. 6.1. Note the way some of the patina has been stripped from the carving due to geochemical weathering processes. Iron Age.

Fig. 6.5. Male anthropomorph on the same large rock panel as above. This probable human figure may be grasping something with its right hand. Iron Age.

This anthropomorph is part of a network of proximate figures, signaling that the underlying meaning of this rock art was derived from viewing it in aggregate.

The exaggerated size of the male sexual organ in many of Spiti’s anthropomorphic depictions serves to emphasize gender identity and the vocational and ceremonial roles that went along with it. Virility, strength and bravery are implicit in these types of depictions, but the complex cultural and social symbolism these qualities carry is beyond our ken.

Fig. 6.6. Anthropomorph armed with bow and arrow on same rock panel as above. Iron Age.

This carving portrays a male hunter. He is wielding a recurve bow, identifiable by the curling tips of the weapon. As in much anthropomorphic rock art in Spiti, the man’s arms point downward.

Fig. 6.7. What appear to be anthropomorphs and animals forming an interconnected melody of figures on the same big rock panel as above. Iron Age and Protohistoric period.

The later petroglyphs are less re-patinated than the Iron Age art. It is difficult to disambiguate what may be humans from animals in these compositions. They run together creating what seems to be a single mass of figures. This demonstrates graphically and probably symbolically too the profound sense of interconnectedness that prevailed between wild caprids and humans in the ancient society of Spiti.

Fig. 6.8. Triangular subject on same large rock panel as above. Iron Age.

The identity of this petroglyph is unknown. It could possibly have been conceived as representing a shrine or some other type of ritual structure, a holy mountain, or any other manner of things.

Fig. 6.9. A curvilinear design or possibly highly stylized wild caprids carved on the same large rock face as above. Iron Age.

Fig. 6.10. Standing archer (lower right side) and three wild ungulates including what appears to be a wild yak (24 cm long) at the top of the composition. Protohistoric period.

Wild yaks are uncommon in Spitian rock art and tend to be concentrated in lower sites such as Gyurmo (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung). This is a typical hunting scene showing a hunter in close pursuit of his prey. This art was lightly engraved in the rock surface, a technique of production not met with in the earliest phase of rock art in Spiti.

Fig. 6.11. A geometric (18 cm high) carving on a small boulder, consisting of a square subdivided into quarters. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

This type of design and squares with an X inside are among the most common rectilinear subjects in the rock art of Spiti. Their meaning and function is a matter of speculation.

Gyu West

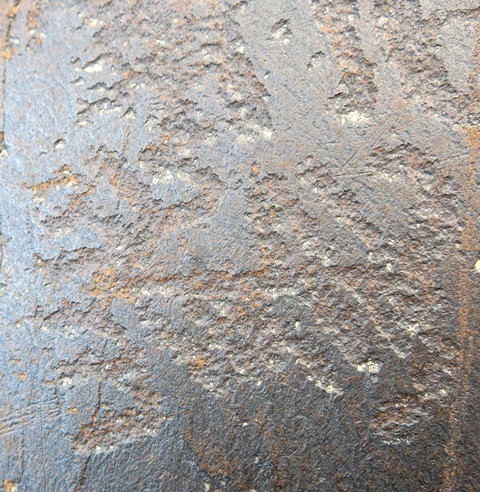

Fig. 7.1. A curvilinear design (12 cm long). Protohistoric period.

There is a great variety of curvilinear subjects in the rock art of Spiti, from simple curls and spirals to labyrinthine patterns. This class of rock art is more common in Spiti than it is in Upper Tibet and Ladakh. It is not known whether this rock art embodies literal representation or abstract forms of meaning or both (pictograms versus ideograms). The sheer diversity of forms extending across all phases of Spitian rock art suggests that curvilinear subjects (they commonly occur as components of complex compositions) had manifold meanings and significance. Some designs may represent highly stylized wild caprids. For more on the possible identities and purposes of geometrics in the rock art of Spiti, see the July 2015 Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 7.2. A six-pointed star (10 cm long). Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Stars are not common in the rock art of Spiti, Ladakh or Upper Tibet. An astronomical or astrological theme may possibly be indicated. This rock art is located on a bench east or down valley of fig. 7.1.

Draknak

Fig. 8.1. A blue sheep (13 cm long) with bow and arrow and hunter (only partially intact) suspended above as if waiting in ambush. The hunter’s head is to the right. Protohistoric period.

This is a fairly standard Spitian hunting scene in subject matter and style. In it a solo hunter on foot aims his bow and arrow at a wild caprid. The hunting of blue sheep or ibex was customarily carried out on foot in what was often difficult terrain. The hunting compositions selected for illustration in this article vary in age and style, but all portray the same set of techniques used in the slaughter of wild ungulates. In order to get near their quarry, hunters must have relied on stealth and/or the outflanking of animals by teams of men working together. In either case much stamina and skill was required. The hunting theme in Spitian rock art, as embodied in a large and diverse body of compositions, must have carried a significant degree of social prestige. As for the mytho-ritual aspects of this rock art, little of a definite nature can be said (for more on this topic, see the July 2015 Flight of the Khyung).

Hounds are not usually shown coursing game in Spiti’s rock art. In the crags and on the steep slopes where blue sheep and ibex spend much of their time, hunting dogs would be of little use. On the other hand, in the plains of Upper Tibet hunting dogs were an important asset and this is reflected in the rock art tableau of that region.

Fig. 8.2. A bowman firing at a wild caprid (blue sheep or ibex; 37 cm long). Protohistoric period.

This is clearly a hunting scene. The trajectory of the arrow used to slay the wild caprid is depicted as a straight line extending from the bow to the animal. The portrayal of arrow trajectories is uncommon in Upper Tibetan and Spitian rock art but more frequent in the rock art of Ladakh. The standing hunter is armed with a recurve bow. In this typical Spitian hunting scene another wild caprid is depicted directly behind the one being slain. Its horns extend beyond the rear quarters of the animal being fired upon. The placement of two wild caprids back to back in this manner is a characteristic depiction in Spitian rock art.

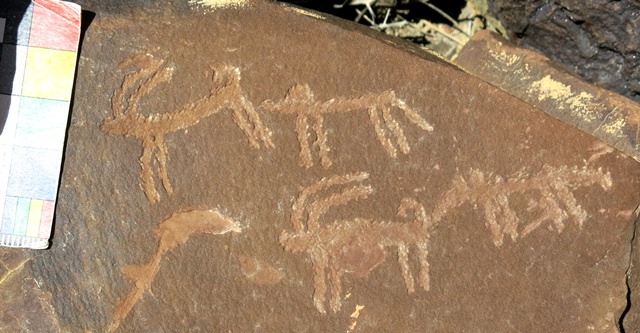

Fig. 8.3. A composite (multiple subjects) hunting scene with four standing archers and four ibexes (each figure up to 14 cm long). Protohistoric period.

These figures were not created by the same hand but in aggregate they convey one of the most common themes in Spitian rock art: the hunting of wild caprids by archers on foot. The hunters with their longish bodies, stick appendages and round heads are emblematic of anthropomorphic depiction in Spiti.

Drakdo Kiri

Fig. 9.1. Up to six congregating blue sheep. Protohistoric period.

In the foreground of this composition are two blue sheep presented in full. Behind each of them are the horns of two more additional blue sheep. This is the kind of perspective one might receive when spying wild caprids from a distance. As noted, this is a characteristic manner of depicting wild caprids in Spiti rock art.

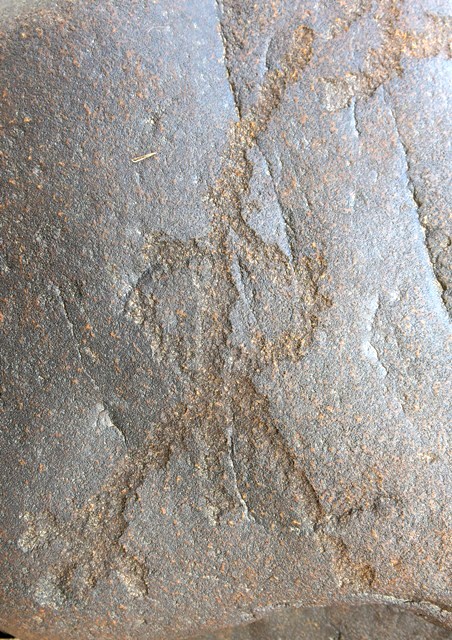

Fig. 9.2. An anthropomorph with what might be a bow. Protohistoric period. The blue paint applied to this boulder marks it out for imminent destruction.

This figure with its relatively wide body, pectoral treatment and short legs is quite unusual. It is situated on the same boulder as figs. 9.3 and 9.4. Like most specimens in Spiti, this anthropomorph appears to be shown without any kind of headgear. In contrast, in Upper Tibet many anthropomorphic figures sport tall coiffures or headgear.

Fig. 9.3. A hunting scene comprised of two or three archers and several wild caprids. Note the archer with the big bow on the middle right side of the boulder. The animals are rendered as stick figures, a common mode of portrayal in Spiti. Protohistoric period. This boulder has been split in two, as a prelude to its complete destruction. Evidently, many boulders have met a similar fate in recent years, eradicating thousands of petroglyphs in Spiti.

This composition showing the hunting of wild caprids is typical. Such scenes are reproduced hundreds of times in the rock art of Spiti. The carvings are not especially adeptly produced, like quite a lot of rock art in Spiti. However, erosion can create the effect of carvings seeming more crudely executed than they actually were.

Fig. 9.4. A standing male archer with what appears to be a wild yak above. This composition is located on the same boulder as fig. 9.2. Protohistoric period.

Wild yaks are uncommon in the rock carvings of Spiti. The bowman is firing at two wild ungulates (not pictured above). The style of this human figure is highly representative of Spitian rock art (stick body and appendages and round head). The display of the male sexual organ is also characteristic. This leaves no doubt as to the sex of most hunters. Such displays of manhood are less common in the rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh. Nevertheless, in Ladakh comparable anthropomorphs are found in both hunting and non-hunting scenes. The figures in Ladakh also have long, thin bodies and appendages, round heads and male genitalia.*

For these figures, see Bruneau 2010, figs, 45, 47, 223, pls. 6, 74; Thsangspa 2014, p. 15 (1.1).

Fig. 9.5. A complex scene of ibexes (including two fully silhouetted specimens, each around 20 cm long), other animals and at least two anthropomorphs. Protohistoric period.

The bulk of figures carved on this boulder appear to form an integrated composition. The group in the upper left portion of the image may constitute a separate composition. Although they are amid animals, the two clearly discernable anthropomorphs in this photo (center and top left) may not be directly involved in the slaughter of animals. Thus a mythological, ritualistic or social theme may possibly be indicated, whether in a hunting or non-hunting context. The bi-triangular anthropomorph in the center of the image is an unusual form in Spitian rock art. This shape is far more common in Upper Tibetan and Ladakhi anthropomorphic depictions. The swastika-like bird in the upper right portion of the photo is discussed in last month’s newsletter (see fig. 20).

Fig. 9.6. Close-up of anthropomorph and two flanking wild caprids on the upper left side of fig. 9.5.

The anthropomorph appears to be depicted with a male sexual organ. It holds a bowlike object in the left hand but it does not appear to be aiming at anything in particular. The raising of the arms as shown in this figure is much less common in Spitian rock art than arms pointing downward. Figures with outstretched arms mostly date to the Protohistoric period or after. Of course, to fire a bow and arrow at least one arm must be somewhat raised. Also, this figure has a bulbous body, another unusual trait.

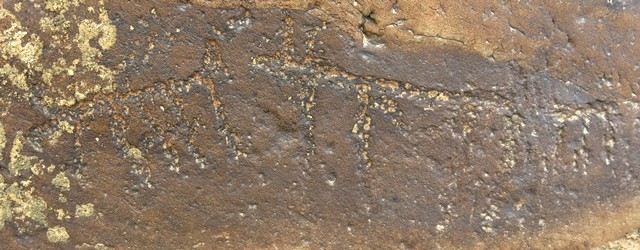

Fig. 9.7. Linear markings on a boulder. The markings on this boulder include a hand-like subject (lower portion of photo). Possibly Iron Age.

This petroglyph is quite heavily stylized, precluding positive identification of the carving as the impression of a hand. Handprints are well known in the rock art of Ladakh but rare in Upper Tibet.*

For handprint rock art in Ladakh, see Thsangspa n.d., sets 4, 5; 2014, p. 24 (fig. f), Bruneau 2010, figs. 52, 184, 198, 201–203, pls. 10, 17, 98. There is one handprint engraved in the round section (bum-pa) of a chorten documented in Upper Tibet, which dates to the Early Historic period.

Gyari

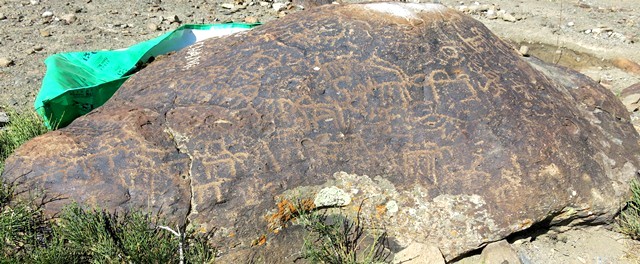

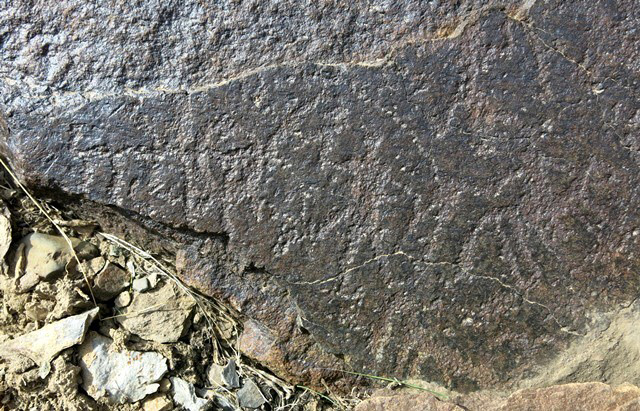

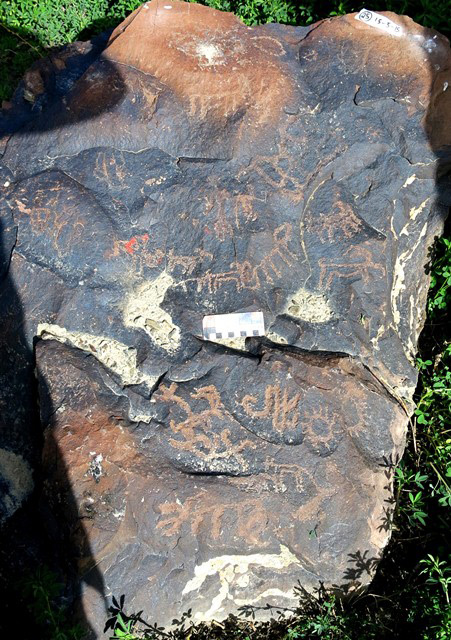

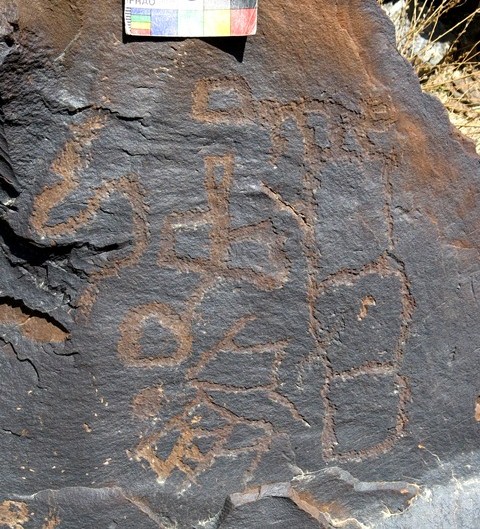

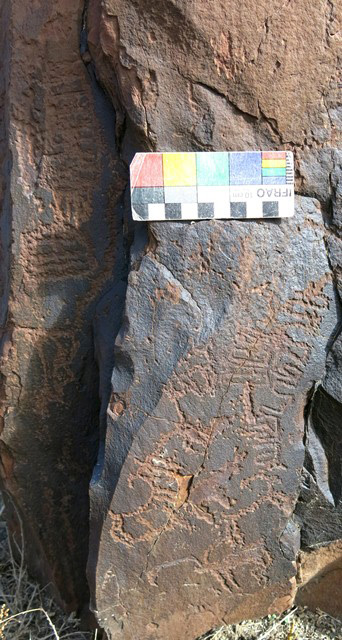

Fig. 10.1. Wild caprids (and other animals?) and at least two anthropomorphic figures. Protohistoric period. The color calibration scale in the photograph is 10 cm in length.

The anthropomorph near the middle right edge of the boulder is a patently male figure. The anthropomorph on the lower left side of the rock also appears to be male. These two figures do not seem to be hunting. Like a fair proportion of Spiti rock art, these petroglyphs were not executed to a very high esthetic standard. Nevertheless, it appears that a rich array of narrative, mythological or ritual materials is embodied in such complex compositions. It is not know how many people were responsible for the ornamentation of this boulder but by the style, technique of carving and physical condition, many of the petroglyphs appear to form an integrated assemblage.

Fig. 10.2. Anthropomorph (13 cm high). Iron Age.

This figure has angular appendages with arms pointing downward, which is emblematic of early anthropomorphic rock art in Spiti. There are anthropomorphic figures in Ladakh and Upper Tibet with arms oriented towards the ground but this gesture or aspect is much more common in Spiti.* This rock art may possibly predate the developed Iron Age (pre-500 BCE). Nonetheless, there are no clear indications that any of Spiti’s rock art is of Neolithic or Bronze Age antiquity.

Anthropomorphic figures in Ladakh and Upper Tibet usually have different forms than Spitian specimens. For a Ladakh anthropomorph with a long, straight body, small round head and rounded stick appendages with arms pointing downward, see Bruneau 2010, pl. 74.

Fig. 10.3. A bowman (9 cm high) aiming at a wild caprid. A non-descript carved line abuts the hunter’s right leg. An animal with a longer tail appears to be pursuing the same caprid. This might possibly be the hunter’s hound or a wild carnivore. The animal to the left appears be a wild caprid. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 10.4. Visible on this boulder are several wild caprids, a spiral (middle left side), archer (middle right side), and a geometric design consisting of an oval with branching interior (upper left side). Most figures date to the Protohistoric period.

Fig. 10.5. Close-up of the archer in fig. 10.4. There are linear projections extending from the waist of this figure.

In the rock art of Ladakh and north Inner Asia (and in Upper Tibet to a much lesser degree) some figures have long objects or embellishments at waist level, but there is no direct correspondence with the figure from Spiti. This is not a common form of anthropomorphic depiction in Spiti.

Fig. 10.6. Wild caprids, one or more anthropomorphs (left side), spiral (upper left side), clockwise swastika (upper middle) and geometric design (middle of lower portion). Protohistoric period.

Most or all figures on this boulder form an integrated composition. Spirals and other kinds of geometric subjects are particularly common at the Gyari site. Like this boulder, they are often interspersed among anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures and sometimes they form interconnected chains of carvings. The geometric at the bottom of the boulder, with its rectilinear and curvilinear elements, touches an ibex situated to the left. The male anthropomorph above and to the left of this ibex may have a bow but it does not appear to be firing at anything particular. A sinuous line above this human form links several figures together. This connecting of figures by lines is commonplace in composite rock art scenes in Spiti. These lines indicate an interrelationship between the various parts of the scenes, drawing wild caprids, humans and symbolic motifs into a singular conceptual or narrative structure.

Fig. 10.7. Close-up of the anthropomorph and surrounding figures on the lower left side of the boulder in fig. 10.6.

Fig. 10.8. Close-up of complex geometric subject merging with ibex on the left in fig. 10.6.

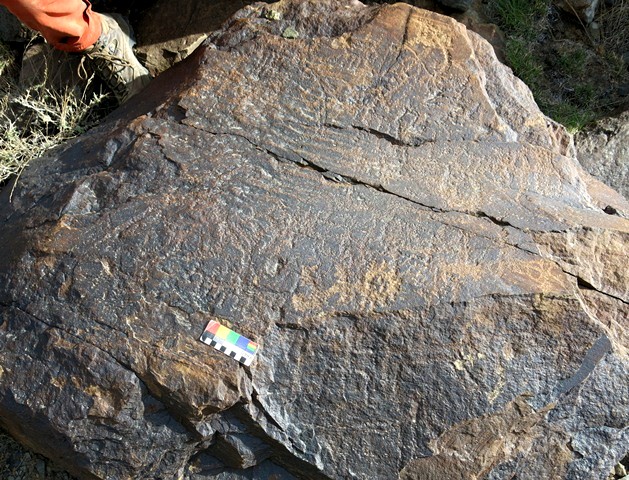

Fig. 10.9. A boulder completely covered with curvilinear designs, most of which form an integrated composition. There are wild caprids interspersed among these designs. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 10.10. The other side of the boulder in fig. 10.9.

Fig. 10.11. Another end of the boulder in figs. 10.9 and 10.10. Note the deeply carved forked line running across the full breadth of the boulder and the intricate curvilinear motif above. There are wavy lines below the forked line. Several animals grace the upper portion of the rock.

One can only speculate about the grand meaning of such rock art. It may possibly possess both narrative and cosmological dimensions. It could also possibly represent the ecosystem of the makers and the various natural structures and processes that gave rise to it. In addition to serving as maps or models, one might speculate that these carvings functioned as magical diagrams to attract game or to enhance the good fortune of the natural or social surroundings. I will not belabor this discussion here, as it can be taken up by others now that Spiti’s rock art is being better chronicled.

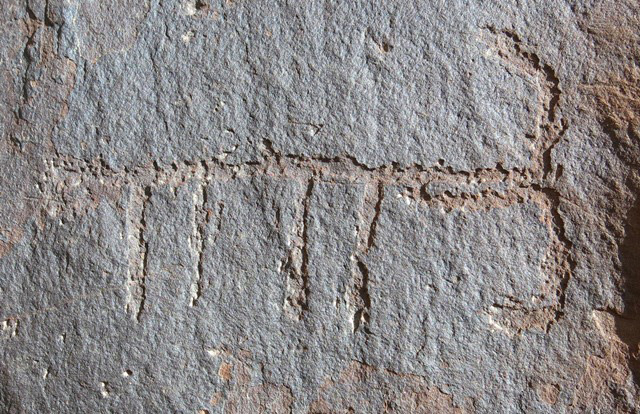

Fig. 10.12. The face of a boulder packed with interconnected geometric designs with several wild caprids distributed among them (bottom left and bottom right). Iron Age.

This complex ornamentation consists of long lines that form contours around the face of the boulder. Short perpendicular lines connect these various incised contours. On the lower part of the rock are six or seven spirals.

Fig. 10.13. Rectangle subdivided into four parts (16 cm long). The right side of this geometric is rounded. Probably Protohistoric period.

There are many such subjects in the rock art of Spiti. They appear with numerous variations. It is not known whether these simple geometrics were conveyors of abstract meaning or figurative representations.

Sahal Thang

Fig. 11.1. A stick figure animal (18 cm long).

This is among the most elementary of styles in Spiti’s repertoire of zoomorphic depiction.

Fig. 11.2. Six or more wild ungulates on smaller boulder. Protohistoric period.

Also on this boulder (right side of image, front and back) are four characters that may belong to a proto-Sarada alphabet (circa 900–1200 CE). They will be examined in the November newsletter. Like the figure 8 in the middle of the boulder, these characters were engraved at a later date than the animal petroglyphs.

Fig. 11.3. One ibex (upper figure) and two blue sheep (lower figures) in a single row (10–14 cm long). Protohistoric period. Most of the non-descript carvings on the same rock belong to a later period.

The uniform style and physical state of the three animal petroglyphs demonstrate that they constitute a single composition.

Fig. 11.4. Four or more wild caprids, semi-circle, oval (14 cm long) and non-descript carvings. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.5. Three or four animals clustered together. It is not clear which way the animal on the upper left side is facing, if indeed this is the depiction of a creature. The figure on the lower left appears to be comprised of two blue sheep oriented back to back. The animal on the right is rendered in a highly unusual style. In addition to the outline of the body, there are two rows of dots that may possibly represent the horns of an ibex. Protohistoric period.

In Ladakh and north Inner Asia the horns of ibex are sometimes rendered or ornamented with lines of dots, which are not unlike the artistic treatment of the Spiti petroglyph.

Fig. 11.6. A blue sheep and more minor figures. Protohistoric period.

As noted, the blue sheep and ibex, the most common animals in Spitian rock art, come in a large variety of interrelated styles.

Fig. 11.7. Three blue sheep and what appears to be a carnivore in pursuit carved on a small boulder. The carnivore could possibly be a wolf or snow leopard, both of which are still found in Spiti. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.8. Three elongated animals (the longest is 18 cm). As these petroglyphs are so stylized, it cannot be determined which species were intended. Lichen has colonized the carvings. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.9. A long-tailed carnivore (13 cm long) attacking a blue sheep. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

The hunting of wild caprids and other animals by wolves and snow leopards has been a fact of life in Spiti since time immemorial. The reproduction of this ecological reality does not only record an aspect of the local natural history but may well have had broader applications related to the personal beliefs of human hunters of wild caprids. Such compositions could have captured the mythological background, ritual praxis or symbolism of hunting activities involving humans.

Fig. 11.10 Two blue sheep and what might be a carnivore occupy the bottom half of the image. Above these carvings more heavily re-patinated figures (including at least two wild caprids) are visible. The hourglass-like figure (upper right) has not been identified. Protohistoric period.

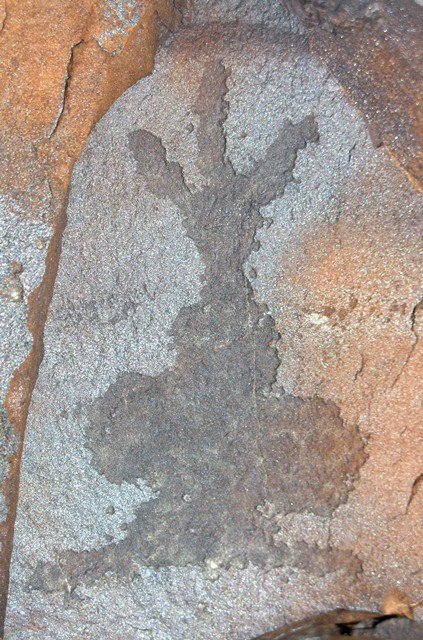

Fig. 11.11. Portrait of an emblematic anthropomorph (20 cm) with hands and fingers gesturing downward. Iron Age.

This is a standard figure in the anthropomorphic rock art of Spiti reproduced (with stylistic and technical variations) at most rock sites in the lower portion of the region (Spi-ti gsham). The angular style and heavy re-patination of this figure indicate that it belongs to the first phase of rock art in the region, which may date as far back as the Early Iron Age. This is one of only a few anthropomorphic figures documented in Spiti with clearly discernable hands. The depiction of hands recalls the rock art of Ladakh, where figures with hands are well represented. Most of these anthropomorphs in Ladakh are shown with hands outstretched or raised up, but specimens with hands oriented downward are also known.* However, these figures are different in form than Spitian examples.

See Thsangspa 2014, p. 22 (fig. h); Bruneau 2010, figs. 121, pls. 76, 77. A class of anthropomorphs with long, straight bodies, thin appendages, male genitalia and downward pointing arms are known from southern Siberia and adjoining regions (Hoppál 2013: 45 [fig. II.2.2]). As a group, however, these Siberian figures bear only limited resemblance to the emblematic anthropomorphs of Spiti. The Siberian petroglyphs are broadly interpreted in Hoppál’s work as shamanic. This may also be the true of cognate figures in Spitian rock art, but other interpretations are just as plausible. These range from portraits of hunters, chieftains and priests to representations of ancestral deities and mythic figures, among other possible identifications. The ancient cultures of Greater Western Tibet were sufficiently diverse and sophisticated that comparison with shamanism (as it is understood from historical and archaeological records) alone is inadequate. For a discussion on the labeling of Upper Tibetan anthropomorphs as shamans, see February 2014 Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 11.12. Male anthropomorph (approximately 30 cm high) with arms akimbo or with hands placed in front of the body at waist level. This figure has an unusually long neck and almost no head. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

This figure is located on the same boulder as fig. 11.4.

Fig. 11.13. Anthropomorph with arms raised and legs spread (14 cm high). The hands of this figure have been depicted. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

In aspect, but not in form, this figure resembles a common class of anthropomorphic art in Ladakh. As with fig. 11.11, these artistic affinities may possibly be attributable to prehistoric cultural interactions between Spiti and Ladakh.

Fig. 11.14. Emblematic anthropomorph (11 cm high) with cross-shaped figure beside it. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Perhaps the cruciform is an unfinished anthropomorph. On the same boulder are several blue sheep petroglyphs.

Fig. 11.15. What appears to be a pair of anthropomorphs. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

These two figures are very different in form. The one on the left displays male genitalia. The head of this figure is engulfed by a carving of unknown identity belonging to the same time period and possibly the same hand. The anthropomorph on the right, if that is what it is, has a large round head, arms that form circles and box-like legs. On the same boulder are another anthropomorph and a blue sheep.

Fig. 11.16. Two anthropomorphs, the larger of which is male. Protohistoric period. A faint line connects these two figures but this appears to have been added subsequently, as was the curvilinear motif above the larger figure.

Fig. 11.17. Male anthropomorph (13 cm high) between two caprids and with a spiral beneath partially buried in the earth. These figures appear to form an integrated composition. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

On this same domed boulder is a dense array of blue sheep most of which may date to the Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.18. The top of this large boulder (2 m x 3 m x 3m) exhibits a large variety of carvings, many dating to the Protohistoric period. At the bottom right is a male figure. Much of the rest of the lower part of the rock surface is covered in a wave pattern, which continues upward and around to the right edge of the rock face. Above and to the left of the wavy lines are two more anthropomorphs, each carved as separate compositions. Sinuous lines are found to the right of these two human figures. Near the top of the boulder is a blue sheep hunting scene, curvilinear motif and two other caprids.

Fig. 11.19. A horse rider (13 cm long). This figure appears to have tall headgear and something in its hands (a bow?). Probably Protohistoric period.

This horse rider is liable to reflect Upper Tibetan influences. Also on the same boulder are several blue sheep and a more recent Tibetan letter A and a vase-like subject.

Fig. 11.20. What appears to be a figure mounted on a horse, arms held out (11 cm long). Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

These stick figures contrast strongly in style with the equestrian art of fig. 11.19.

Fig. 11.21. Two anthropomorphs (top left), curvilinear subject (top right) and more minor carvings. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

These various subjects are closely related thematically and chronologically and seem to form a single composition.

Fig. 11.22. All sides of this domed boulder (3.8 m x 2.5 m) are covered in petroglyphs of wild caprids, anthropomorphs and geometrics. There are more than 100 individual carvings. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

The petroglyphs on this boulder have been damaged recently by orchardists and graffiti artists.*

For a large dense array of wild ungulates and geometrics at the Sabu site in Ladakh, see Bruneau 2010, fig. 103. This mass of figures recalls composite scenes in the rock art of Spiti, but most of the individual figures constituting it are different in style.

Fig. 11.23. Other side of the boulder in fig. 11.22.

Fig. 11.24. What appear to be two ibex shown back to back on the same boulder as fig. 11.22.

This is one of the standard themes in zoomorphic rock art of Spiti.

Fig. 11.25. Wild caprids (blue sheep and ibex) on same boulder as Fig. 11.22.

Fig. 11.26. On this south-facing boulder is a dense array of wild caprids and anthropomorphs. These figures are now highly eroded. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.27. Bowman (14 cm high) attacking wild ungulate. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

The manner of carving and modeling the two figures gives them a blotchy appearance.

Fig. 11.28. Standing archer stealthily hunting ibex (14 cm long) from behind. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.29. Three anthropomorphs, at least two which are armed with bows, hunting blue sheep, one of which is clearly represented. These petroglyphs have undergone much wear. Protohistoric period.

These carvings are closely related to one another and may possibly form an integrated composition.

Fig. 11.30. Male archer taking aim at an ibex. Above these two figures is another wild caprid. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.31. Male archer shooting at a blue sheep, one of three caprids making up the composition. Note the exaggeratedly large arrow of the hunter. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

The hyperbolic arrow of the hunter seems to convey its effectiveness at dispatching blue sheep. There are carvings on all sides of this boulder, including two or three yaks (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 36).

Fig. 11.32. One or two anthropomorphs and at least four animals. The animal on the far right seems to have the appearance of a carnivore. It is not clear if this is a hunting scene or some other type of activity. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.33. On this boulder can be seen a bowman (upper middle of photo) surrounded by his prey, wild caprids. In the center of the boulder is a linear motif that is almost letter-like. Animals and other figures occupy the lower part of the rock. Protohistoric period.

This is another variation on the standard hunting scene in Spiti rock art. They differ in style and production, reflecting many centuries of artistic endeavor.

Fig. 11.34. A standing archer in typical Spitian fashion, save for the raising up of his clearly depicted hand. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

The depiction of a hand gesturing upward is reminiscent of Ladakhi rock art, where it occurs in many different contexts. Such portrayals are not found in Upper Tibet. The presence of this motif may possibly be attributable to artistic influences originating from Ladakh.

Fig. 11.35. Archer and five wild caprids. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.36. Standing archer and what may be an argali sheep (gnyan; 23 cm long). The argali is well known for its large curling horns. Protohistoric period.

That argali were occasionally found in Spiti is confirmed by Egerton (1864: 88). On the flat top of this boulder there are also around a dozen blue sheep carvings.

Fig. 11.37. Geometric subject consisting of two joined squares subdivided into quarters. Early Historic period.

This petroglyph is located on the same boulder as fig. 11.23.

Fig. 11.38. Rectangle containing various curvilinear elements (12 cm high) on the north side of a boulder. Protohistoric period.

The identity of this geometric subject is unknown. Among its elements there may possibly be a sun, crescent moon and wild caprid.

Fig. 11.39. Curvilinear subject possibly with anthropomorphic traits (14 cm high) on same side of boulder as fig. 11.38. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.40. Interlinked squares resembling a Grecian border design (rGya-nag lcags-ri). Early Historic or Vestigial period.

This type of border is a very common form of ornamentation in Tibetan objects of the historic era.

Fig. 11.41. Ax-shaped subject with two circles in it (17 cm high). Protohistoric period.

The outline of this figure bears some resemblance to a mascoid carved in Ruthok (see December 2011 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 11). However, the mascoid has a more complex array of lines and circles in it.

Fig. 11.42. East side of boulder with various geometrics and wild caprids. Near the middle of the boulder is a square subdivided into six parts, four of which contain diagonal lines forming an X. Protohistoric period.

As noted, squares with an X are common in the rock art of Spiti. They are also known in Ladakh and Upper Tibet and in other parts of the world as well. This design occurs in thokcha (thog-lcags), a heterogeneous class of Tibetan copper alloy talismans. On the south side of the same boulder are various animal carvings.

Fig. 11.43. A mass of interconnected circles and curved lines spread across the top of a boulder. Much of the veneer that once encased the upper part of the rock has been worn away. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.44. A curvilinear subject (16 cm long). Protohistoric period.

This carving is located on the same boulder as fig. 11.41.

Fig. 11.45. Circles, other curvilinear designs, animals and miscellaneous figures of diver’s periods. Note the Tibetan letters n and d on the upper right side of the boulder. Above these letters is a bird-like creature and above it is a conjoined sun and moon.

Fig. 11.46. A concentric circle design (7 cm in diameter). Protohistoric period.

There are wild caprids and other figures on this boulder.

Fig. 11.47. A spoked wheel. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Spoked wheels of similar design are found in both Upper Tibet and Ladakh.* There are an anthropomorph and animals on this same boulder as well.

For a specimen from Ladakh, see Bruneau 2010, fig. 215. In Upper Tibet spoked wheels are solar symbols and chariot wheels. For example, see Bellezza 2008, p. 165 (fig. 277).

Fig. 11.48. Conjoined sun and moon (right side), horse with saddle-like object on its back, complex geometric design with eye-like top and other figures. Early Historic or Vestigial period.

Fig. 11.49. Three swastikas oriented in different ways. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

These swastikas are situated on the same boulder as illustrated in fig. 11.21. There are other petroglyphs on this boulder too.

Fig. 11.50. Geometric forms of unknown identity. The figure on the right (with triangular lower half and circular upper half; 14 cm high) appears to have a long line extending from the top that terminates in what looks like a conjoined sun and moon. If this discernment of the form is correct, it may identify the figure as a ritual object or ceremonial structure. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 11.51. An unusual subject (20 cm high) that was very carefully executed. It may possibly represent an actual ritual object or structure. This specimen is located above the petroglyphs in fig. 11.50, which may have been made in imitation of it. The upper portion of this carving consists of three circles, each with a smaller circle carved inside. The lower portion is rectilinear in form and tapers inwards towards the top. There are inner lines paralleling the ones forming the outline of the figure and inside those lines are other carved elements. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11.52. Another unusual subject of unknown identity (18 cm). Early Historic period.

Using Tibetan material culture as a reference point, possible identities of this enigmatic object include offering vase (bum-pa), ritual cake (gtor-ma, ’brang-rgyas), portable receptacle or permanent shrine of a deity (rten).

Fig. 11.53. A pair of highly unusual subjects (each around 10 cm in height). The specimen on the left is triangular with four circles arrayed along its outer sides and a dot in the middle. The specimen on the right is also triangular and has two outer circles and several central dots. Extending above the apex are three vertical lines. Protohistoric period.

These two petroglyphs may have been made at different times but their forms complement one another. They resemble offering sculptures albeit ancient variants. The finial of the example on the right is reminiscent of the ‘horns of the birds, sword of the bird’ (bya-ru bya-gri) of the Yungdrung Bon religion.

Fig. 11.54. This seems to be another subject of the same class as those pictured above. This example has the distinct appearance of a shrine or other ritual structure. Protohistoric period. The finial consists of seven lines, one of which forms a triangle. The upper portion of the carving is rounded with two subsidiary circles flanking it and a dot in the middle. The lower portion is pyramidal with a triangular inner element. Protohistoric period.

Both figs. 11.53 and 11.54 have some correspondence with ritual structures and shrines in the rock art of Upper Tibet. The closest correspondence pinpointed is with a petroglyph at the Sabu site in Ladakh, which has a similar finial but with five lines instead of seven lines (see Bruneau 2010, fig. 101). The body of the Sabu carving is like that of a shrine.

Fig. 11.55. Cup-marks carved into the surface of a boulder. These marks are heavily re-patinated and of significant age.

Cup-marks are found in rock art worldwide. They are however not very common in Spiti. These should not be confused with circular holes bored in limestone formations, which were used as mortars in Spiti. There is also a geometric subject on this boulder consisting of a rectangle bisected by a diagonal line.

Tibtra

12.1. Two animals and unidentified subject. Probably Early Historic period. Photo courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

Tsen Tsalep

Fig. 13.1. Four or five wild caprids on a boulder. Protohistoric period.

As was customary in Spiti rock art, these figures are joined together, or almost so, in what was presumably a demonstration of caprid social behavior.

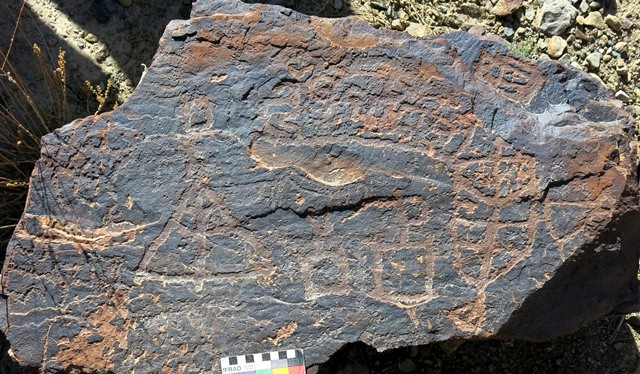

Fig. 13.2. A boulder with many anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures. Most of these petroglyphs can be attributed to the Protohistoric period. Note how the middle portion of the surface of the boulder is missing. This loss occurred long ago, as the missing section is heavily re-patinated and eroded and hosts several ancient petroglyphs.

The loss the middle part of this rock is puzzling. From adjacent petroglyphs both above and below the missing section, it can be seen that older rock art extended to it. Perhaps natural forces were responsible for this massive exfoliation of the rock surface, but anthropogenic factors cannot be ruled out. If humans were involved, it might mean that this rock art was deliberately destroyed. If the latter scenario has any validity, perhaps individual or clan rivalries can be implicated.

Fig. 13.3. A part of the upper portion of the boulder in fig. 13.2. Animals and perhaps other figures are portrayed here.

Fig. 13.4. A view of the lower portion of the boulder in fig. 13.2. To the right of several wild caprids stands an anthropomorph one arm raised and one down. It is not obvious that he is hunting. To the right of this anthropomorph is a figure that appears to be on horseback, an uncommon subject in Spitian rock art.

Fig. 13.5. Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic rock art of various phases. To the right of the color calibration scale is an emblematic anthropomorph. Due to heavy erosion and the mingling of figures, few petroglyphs are readily identifiable on this boulder.

Fig. 13.6. A number of wild caprids arrayed diagonally across a boulder. Note the spiral on the upper right side of the rock. Protohistoric period.

Many of these figures appear to constitute an integral composite scene.

Fig. 13.7. Ibex of the Protohistoric period (upper figure) and horse rider of the Early Historic or Vestigial period (lower figure).

These two petroglyphs were created using different techniques. The ibex was gouged from the stone one chip or flake at a time. The horse rider was engraved using a sharp ferrous implement for cutting the rock surface.

Lari Tingjuk

Fig. 14.1. An ibex carved in a fairly unusual style (7 cm long). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.2. Two wild caprids (each 9 cm long). Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 14.3. A wild ungulate (17 cm long). Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

It is unusual in Spiti rock art for the horns of wild ungulates to form a complete circle. However, this motif is well known in early rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh.

Fig. 14.4. This appears to be the unfinished wild ungulate (12 cm long). Only the body and rear quarters were carved. Protohistoric period.

The volute motif on the left portion of the carving and the fine engraving technique used are reminiscent of Eurasian animal style art in Upper Tibet and Ladakh, however, few examples of this genre of figuration have been discovered in Spiti and none of them include depictions of wild ungulates (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung). Thus this petroglyph appears to be an anomaly. On the vertical face of the same boulder are petroglyphs of animals and other figures.

Fig. 14.5. An unusually styled wild ungulate whose body appears to have contained a carved design resembling stripes or squares (18 cm long). The long vertical line on the right may represent the horns of another animal. Protohistoric period.

There are several other wild ungulate carvings on the same boulder.

Fig. 14.6. A depiction of one or perhaps two blue sheep in front of one another (13 cm long). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.7. An ibex rendered in a typical style (13 cm long). Protohistoric period.

There are various other caprids carved on this boulder. Unfortunately, this rock was recently split in two.

Fig. 14.8. Boulder with a variety of blue sheep in common styles. Protohistoric and Early Historic periods.

Fig. 14.9. Blue sheep (19 cm long). Protohistoric period.

There are other caprids and geometrics on this boulder.

Fig. 14.10. Deer (top left), wild yak (top right), horned eagle (lower left), emblematic anthropomorph (lower right). Iron Age and Protohistoric period.

For a discussion of these compositions, see last month’s newsletter, fig. 15.

Fig. 14.11. A stick figure blue sheep (13 cm long). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.12. Four highly eroded quadruped carvings. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.13. Two pairs of ibexes pursued by long-tailed carnivores. Early historic period.

As we saw last month, there are a number of rock art compositions in Spiti depicting this theme. They may possibly have served as an archetype or sacred model for hunters.

Fig. 14.14. Two pairs of blue sheep being attacked by carnivores. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.15. A deer with elaborate branched antlers in a linear style of depiction (10 cm long). Iron Age.

Deer tend to belong to earlier phases of rock art in Spiti. Perhaps this means that cervids became extinct in the region quite early on.

Fig. 14.16. A deer carving with prominent antlers (10 cm long). This petroglyph has undergone much wear. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

In close vicinity to this carving are those of a blue sheep and ibex.

Fig. 14.17. Portrait of two ibex (each approximately 10 cm high) with two nondescript carvings above belonging to the same composition. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.18. Typical carvings of wild caprids covering the upper surface of a boulder as well as two suns and swastika (bottom half). Protohistoric and Early Historic periods.

Fig. 14.19. Four wild ungulates (the top two are joined back to back in a typical form of depiction). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.20. A possible snake carving (20 cm long). Protohistoric period.

It is reported that small snakes live in the rocks of Spiti as far up the valley as Lari. In Tibetan tradition snakes are most closely identified with water spirits (klu and klu-mo).

Fig. 14.21. A possible snake. Protohistoric period.

On this same boulder are wild ungulate carvings.

Fig. 14.22. A solitary anthropomorph. Although this style (wide torso) is not common in early Spiti rock art, the figure holds its arms downward, a conventional mode of depiction. This figure appears to be wearing a wide-brimmed hat or it has a pair of horns. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.23. What appears to be a figure squatting on a horse with its arms raised (15 cm long). It may have male genitalia depicted. Protohistoric period.

It is possible that rather than a human, this could be the portrait of a divine or mythic figure. Many Tibetan deities are mounted on horses.

Fig. 14.24. Horse rider (20 cm long). Early Historic period.

There are geometrics on this same boulder belonging to a variety of periods.

Fig. 14.25. Emblematic anthropomorph with arms brought around to its sides (center; 17 cm high) and caprid (left) possibly belonging to the same composition. To the right are two or three other compositions consisting of geometric subjects and a wild caprid in the middle. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.26. Anthropomorph (13 cm high) and animal that may form a single composition. Protohistoric period.

There are a number of other animals on this boulder.

Fig. 14.27. Anthropomorph, arms at its sides with male genitalia (top right; 11 cm high), and three wild caprids in an integrated composition. Protohistoric period. A fourth wild caprid (bottom) is attributable to the Early Historic period.

Fig. 14.28. Anthropomorph with arms raised (center top) and at least four wild caprids and what might be a horse (large figure on right side) forming an integrated composition. Early Historic period. On the top left is a triangle and square.

Fig. 14.29. Two emblematic anthropomorphs (8 and 9 cm high) and caprid (partially visible to left) forming a unitary composition. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.30. Anthropomorph (11 cm high) surrounded by wild caprids. The anthropomorph and other less re-patinated figures appear to date to the Early Historic period. More highly worn and re-patinated figures at bottom left are attributable to the Protohistoric period.

With its wide body and an appendages conveying movement this anthropomorph is in a style characteristic of the Early Historic period.

Fig. 14.31. Anthropomorph with arms raised and widely spread legs (right). Early Historic period. On the left side of the boulder are two clockwise swastikas and star (bottom) that can also be dated to the Early Historic period. Above the star there is an older petroglyph resembling an anthropomorph.

The small head and the stick body, appendages and male genitalia epitomize early anthropomorphic art in Spiti. However, these motifs occur with raised arms and a bent torso (expressing movement), which are stylistic and symbolic innovations of the Early Historic period.

Fig. 14.32. An integrated composition comprised of anthropomorph (left), sun and crescent moon (middle) and blue sheep (right). Protohistoric period. Below these figures is a wild caprid that may belong to another composition.

This composition with the sun and moon between an ostensibly human figure and blue sheep appears to convey mythological and/or cosmological information. By virtue of being on both ends of the scene, the human and animal appear to be counterparts in a relationship modulated or generated by the sun and moon as principle cosmogonic symbols.

Fig. 14.33. An ordinary Spitian hunting scene portraying an archer (11 cm high) attacking a wild caprid. Above these figures are two more wild caprids. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.34. A wild caprid and archer made at different times. It appears that the archer (Early Historic period) was added later to create a hunting scene.

Perhaps by adding a hunter the maker was attempting to recapture some of the ancient hunting magic or good fortune incumbent in the wild caprid carving, but I hasten to add that this is pure speculation.

Fig. 14.35. A male archer (11 cm high) attacking what appears to be a male argali sheep. The hunter may be wearing a hat with a brim. Iron Age.

Wild caprids depicted with male sexual organs are uncommon in the rock art of Spiti. Such depictions are more common in Ladakh and Upper Tibet.

Fig. 14.36. On top of this boulder there appear to be several wild caprids carved amid curvilinear designs including a large central circle. Protohistoric period. On the side of the boulder are wild caprids and other carvings of the Early Historic period.

Fig. 14.37. Ibex (top) and a number of geometric forms. Protohistoric and Early Historic periods.

Fig. 14.38. Intricate rectilinear subjects composed of recurring patterns in parallel. Protohistoric period.

It appears that several different hands were responsible for creating these carvings.

Fig. 14.39. Complex square design (top) and blue sheep (bottom) that appear to form an integrated composition. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.40. Ibex (lower left), double spiral (lower right) and a host of other not easily recognizable carvings. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.41. Boulder with linear patterns (top half) and ibex and other wild caprids (bottom half). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.42. Curvilinear subjects covering the face of a boulder interspersed with wild caprids. In the middle of the image is a rectangular form that appears to consist of two wild caprids standing in opposite directions. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.43. Wild ungulates and linear markings of typical Spitian style. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.44. Rectilinear subjects forming complex patterns with few if any animals portrayed. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.45. Series of arched lines and square divided into quarters (middle of bottom). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.46. A complex geometric subject that possibly integrates wild ungulates into its design. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.47. A circle with curvilinear patterns inside and above. Protohistoric period. The animal (lower left) was added at a later date.

Fig. 14.48. A complex rectilinear subject comprised of square and circular cells. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.49. Bisected ovals. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.50. Two geometric subjects, one round with a spoked pattern and one oval with radiating lines, which appear to have been engraved in the rock together. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.51. Three circles with connecting line. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.52. Spiral. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.53. Curvilinear design of much intricacy and fluidity. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

There is a class of copper alloy talismans (thog-lcags) with complex geometric designs that includes a similar pattern.

Fig. 14.54. Sub-rectangular form divided into four parts. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.55. A square divided into four quarters (6 cm high). Protohistoric period.

This is a common subject in Spiti rock art. Also on the same large boulder are various animals and other figures.

Fig. 14.56. Square with X (13 cm long). Protohistoric period.

This is a common geometric subject in Spiti. It is also found in Ladakh, Upper Tibet and in many other parts of the world.

Fig. 14.57. Square with partial X (10 cm high). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.58. Combined squares (23 cm long). The upper right one is divided into four portions at least two of which have circles in the middle. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.59. Hourglass-shaped subject (top right), flaming jewel-like subject (bottom right), complex rectilinear design comprised of joined squares some of which have internal elements (middle) and letter-like designs (left side). Part of the figure that resembles the letter R was carved at a later date. Early Historic or Vestigial period. The letters PO were carved over the right side of the complex rectilinear subject.

Fig. 14.60. Square divided into nine parts (middle) and lesser geometric forms. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.61. Bisected triangle (left), two squares (middle of bottom), sub-rectangle subdivided into eight parts with triangular extension (right side) and complex geometric pattern (top). Probably Early Historic period.

Fig. 14.62. Design resembling the Tibetan letter cha (left), possible wild caprid (middle) and subject combining rectilinear and curvilinear forms. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.63. One or two wild caprids (lower left), rectangle divided into quarters (bottom right), geometric subject including triangle (extreme right), wild caprid (middle of top) and curvilinear subject (upper left). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.64. Complex geometric design covering the face of a boulder. It includes long vertical lines and shorter connecting horizontal lines. Some of these carvings have been obliterated. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.65. Hourglass-shaped subject (13 cm long). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.66. A tree-like subject with seven branches some of which are forked (23 cm wide). Protohistoric period.

This intriguing petroglyph may have both figurative and symbolic components.

Fig. 14.67. Tree-like form with swastika on top. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.68. A carving that seems to depict a ritual object or shrine with a tricuspidate finial, rounded middle section, wide overlapping lower section and broad foot (10 cm high). Protohistoric period.

Similar finials are found in the depiction of ceremonial monuments in Upper Tibet.

Fig. 14.69. Another possible ritual object or shrine. Part of the left side of this carving has been destroyed. This petroglyph has a wide triangular finial with a wedge-shaped top, thin neck, circular middle section with curvilinear designs, triangular lower section and rectangular base. Note that parallel lines were used in the creation of the outline of this figure. It is also possible that this is the representation of a raptor. Those resembling this subject are known in Spitian rock art (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung, figs. 17, 18). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.70. Two circles, triangle and two crescents. The larger circle has a diameter of 6 cm. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

This is another composition that may depict both symbols and figurative representations. In any case, a cosmological or cosmogonic theme seems indicated.

Fig. 14.71. Two suns with eight rays each (middle), tiered shrine (lower right) and unidentified subject (upper left). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 14.72. Symbol or figure resembling a Tibetan thunderbolt (rdo-rje; left side, 8 cm high) and cruciform symbol or figure (right). Probably Protohistoric period.

Fig. 17.73. Three swastikas, the largest of which is 12 cm high. Protohistoric period.

As noted in the July 2015 Flight of the Khyung, the swastika is a symbol laden with meaning in the Tibetan cultural world, but it is not clear how any of this specifically pertains to these petroglyphs.

Fig. 14.74. Two counterclockwise swastikas interconnected by long line with a loop in the middle. Protohistoric period.

Bibliography

Bellezza, John V. 2008. Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet. A Historical and Ethnoarchaeological Study of the Monuments, Rock Art, Texts and Oral Tradition of the Ancient Tibetan Upland. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse Denkschriften, vol. 368. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Bruneau, Laurianne. 2010. “Le Ladakh (état de Jammu et Cachemire, Inde) de l’Âge du Bronze à l’introduction du Bouddhisme : une étude de l’art rupestre, vol. 3. Répertoire des pétroglyphes du Ladakh”. Ph.D. dissertation, Université Paris I-Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Egerton, Philip Henry. 1864. Journal of a Tour Through Spiti to the Frontier of Chinese Thibet. Reprint, Bath: Pagoda Tree Press, 2011.

Hoppál, Mihály. 2013. Shamans and Symbols: Prehistory of Semiotics in Rock Art. Budapest: International Society for Shamanistic Research.

Schaller, George, B. 1998. Wildlife of the Tibetan Steppe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Thsangspa, Tashi Ldawa. 2014. “Ancient Petroglyphs of Ladakh: New Discoveries and Documentation” in Art and Architecture in Ladakh: Cross-cultural Transmissions in the Himalayas and Karakorum, pp. 15–34. Leiden: Brill.

____N.d. Petroglyphs of Ladakh: The Withering Monuments http://www.tibetheritagefund.org/media/download/petroglyphs.pdf

Vernier, Martin. N.d. Exploration et Documentation des pétroglyphes du Ladakh, 1996-2006. Fondation Sierre: Carlo Leone et Mariena Montandon.

Next Month: More awe-inspiring rock art of Spiti!