October 2017

John Vincent Bellezza

Join us for another Flight of the Khyung, your portal to the riddles of ancient Tibet! This month’s newsletter contains the second part of an article about fierce wild animals in the rock art of Upper Tibet. There are many pictures on view showing sleek carnivores chasing prey and acting as prime agents in compositions laden with magical meaning. The second feature in this newsletter reviews a recent article by Taylor et al. on the domestication of the horse in Mongolia and its role in burials of the Late Bronze Age. The third and final feature reviews an article on prehistoric textile discoveries made in Mustang, written by Gleba et al. This review contributes to our understanding of early exchange networks on the Tibetan Plateau. Please read on to uncover the prehistoric mysteries of innermost Asia.

For those interested in rock art depictions of cosmic birthing figures on the Western Tibetan Plateau, another example has been added to the August 2017 newsletter. See “Obscured for Centuries: The Lost Rock Art of Lo Mustang”, Part 2, fig. 9d.

The Prototypic Hunters of the High Plateau: Wild carnivores in the rock art of Upper Tibet – Part 2

See last month’s Flight of the Khyung for the first part of this article.

Gallery of Images

Group 4: Wild carnivores hunting wild ungulates

This largest group of wild carnivore rock art in Upper Tibet features one or more wild carnivores in close pursuit of prey. Wild carnivores are shown stalking and coursing their quarry in a variety of aspects. They mostly approach wild ungulates from the rear but also sometimes from the front. In a few compositions, wild carnivores are depicted devouring their kill.

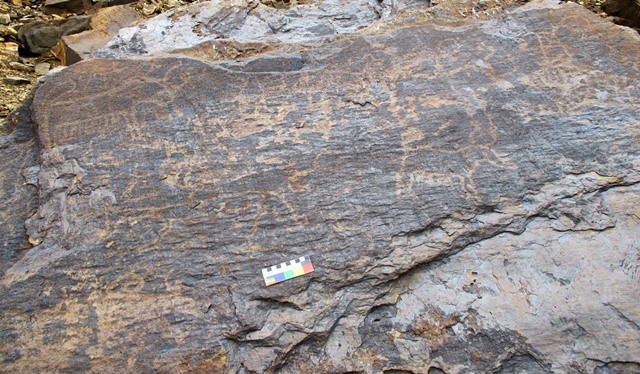

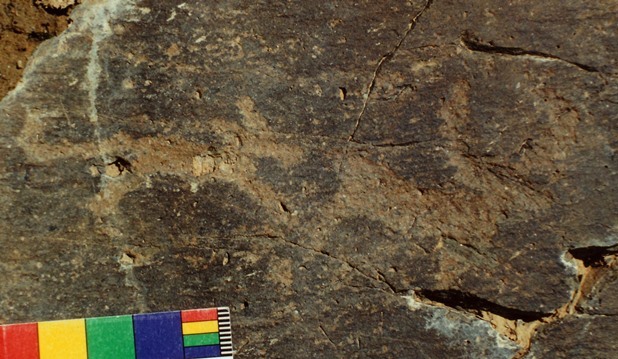

Fig. 28. Top of boulder carved with interrelated scenes of wild felines attacking wild yaks and caprids and other wild yaks

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Fig. 29. Wild carnivore attacking one or two wild yaks (pictured on upper right side of fig. 28)

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: flat back; tail overarching back, spiral at the end; pointed muzzle; two flexed legs with clawed feet

Body: lines forming a checker pattern, probably simulating spots or stripes

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Additional details: The counterclockwise swastika above the wild carnivore may not be an integral part of the composition. They do however appear to have been made in the same time frame.

Fig. 30. Wild carnivore attacking wild caprid (pictured on lower left side of fig. 28)

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: flat back; tail overarching back, spiral at end; four legs

Body: lined, probably simulating stripes

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Additional details: With its curling horns and stout body, the quarry most resembles the argali sheep (gnyan).

Fig. 31. Wild carnivore and wild yak

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: concave back; tail overarching back, spiral at end; two flexed legs with clawed feet

Body: lines forming a checker pattern, probably simulating stripes or spots

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Additional details: Situated among other wild felines and wild yaks and perhaps a standing anthropomorph, which form one or more integral compositions. This rock art is highly worn and not easily identifiable. It is located on a different part of the boulder than that illustrated in fig. 28.

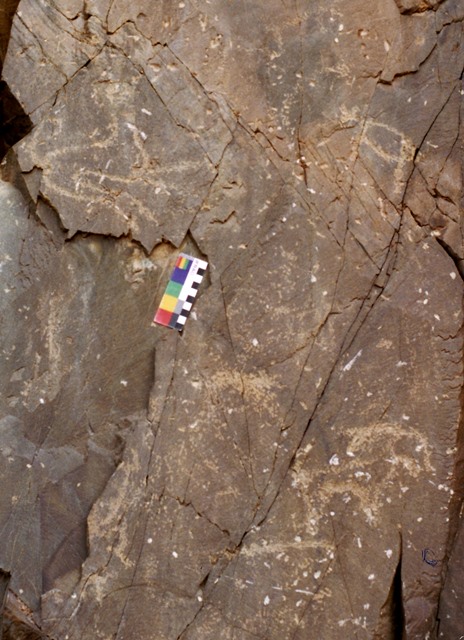

Fig. 32. Two wild carnivores attacking two wild yaks

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: flat back; tail overarching back, spiral at end; upright ears; gaping mouth; two flexed legs with clawed feet

Body: lined, probably simulating stripes/silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

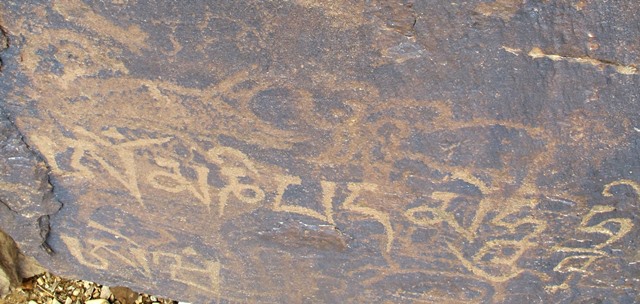

Fig. 33. Wild carnivore attacking wild yak (incomplete) with mani mantra and Sanskritic affirmation (Early Historic period) partially superimposed and other figures below

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: arched back; tail overarching back, spiral at end; upright ears; gaping mouth; two flexed legs with clawed feet

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Additional details: Found on same boulder as fig. 32. The three or more petroglyphs below the carnivore attack scene have not been positively identified. One of them appears to represent a wild yak.

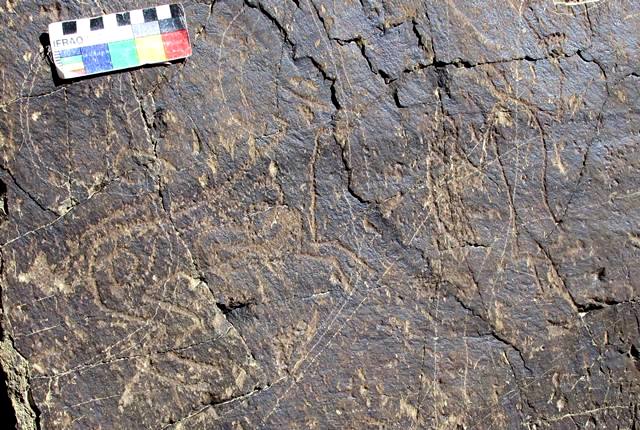

Fig. 34. A pair of wild carnivores devouring prey (upper left), lone carnivore (lower left), three wild carnivores devouring prey (lower right) and other wild ungulates

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; tail downward pointing tail, curled at end; upright ear; gaping mouth; two flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Additional details: Located on boulder with many other figures including chariots (see August 2010 and March 2012 (figs. 9, 10) Flight of the Khyung). All wild ungulates pictured appear to be argali or blue sheep.

Fig. 35. A pair of wild carnivores devouring prey (on same boulder pictured in fig. 34)

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; tail downward pointing tail, curled up end; upright ears; gaping mouth; two flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Fig. 36. Wild carnivores pursuing wild caprid with mani mantra (Early Historic period) partially superimposed (on same boulder pictured in fig. 34)

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; tail downward pointing tail; upright ears; squared muzzle; two flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

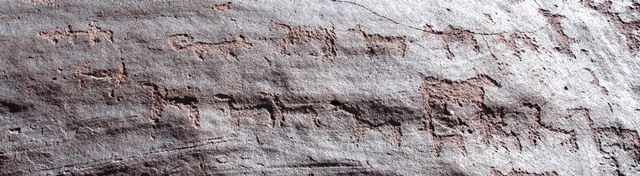

Fig. 37. Two rows of figures, each consisting of a wild carnivore confronting wild ungulates that appear to form an integral composition

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: concave/arched back; tail spiraling/upward pointed tail; upright ear; rounded muzzle; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Additional details: The lines of wild ungulates may be comprised of wild asses. One other quadruped is situated to left of wild carnivore in upper row. On the same boulder is a chariot (see August 2010 Flight of the Khyung).

Fig. 38. Two wild carnivores pursuing stag

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: flat back; straight tail; upright ears; rounded/pointed muzzle; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 39. Two carnivores pursuing stag and what may be two mounted hunters that appear to form an integral composition

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: flat back; straight/downward pointing tail; upright ears; pointed muzzle; two/four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: The hunters (bottom middle) possibly present in this scene suggest that the carnivores may be hunting dogs and not wild carnivores. Alternatively, this may be a prototypic hunting scene, modeling the human type on the wild animal type.

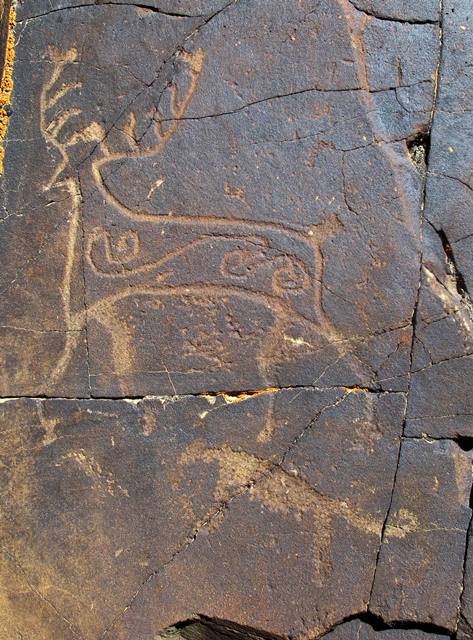

Fig. 40. Wild carnivore pursuing stag

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: flat back; tail overarching back, spiral at end; eye; gaping mouth; four flexed legs

Body: with complex volute motif

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: The stag also exhibits a complex body motif consisting of interconnected volutes. Both prey and predator stand on the tips of their feet. This composition belongs to the Upper Tibetan branch of the Eurasian animal style. Also, see October 2014 (fig. 26) and November 2014 (fig. 67) Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 41. Wild carnivore pursuing stag

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; straight tail, curled at end; pointed muzzle; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: The stag sports a triple volute body motif. For this image, also see October 2014 (fig. 17) Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 42. Wild carnivore pursuing one or more stags with mani mantra superimposed on top

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: straight back; tail overarching body, spiral at end; gaping mouth; two flexed legs

Body: lined, probably simulating stripes

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Additional details: One antler of a stag is partially cut in photograph. Other stags and a wild yak, also in the Eurasian animal style, are found in close proximity but appear to belong to other compositions. Also see October 2014 (figs. 29, 30) Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 43. Wild carnivore pursuing a wild yak and other wild ungulates with mani mantra partially superimposed

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: straight back; tail overarching back, curled at end; two flexed legs

Body: lined, probably simulating stripes

Technique: lightly carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Additional details: The wild feline was engraved somewhat differently than the wild yak immediately to the right, suggesting that they might not be part of the same composition. The technique used to carve the wild yak more closely matches deer and wild caprids located above and below it.

Fig. 44. Wild carnivore pursuing stag, with another wild deer above (partially visible) that may possibly be part of the same composition

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: arched back; tail overarching back with spiral at end; upright ears; gaping mouth; four flexed legs

Body: lined, probably simulating stripes

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: For a more encompassing view of these figures, see October 2014 (fig. 20) Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 45. Carnivore pursuing wild caprid (upper) and standing archer firing arrow at wild ungulate (possibly wild ass) with carnivore in pursuit (lower), which may possibly form an integral composition

Taxa: probably canine

Prominent motifs: flat back; downward pointing tail; upright ears/no ears; pointed muzzle; four unflexed/flexed legs

Body: silhouetted/outlined

Technique: deeply/moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: The lower portion of the archer and his bow have broken away. The arrow is shown in flight, an unusual depiction in Upper Tibetan rock art. The upper carnivore may be a wild variant, paralleling the lower hunting scene with the archer and what may be his hunting dog. Thus, this could possibly be an example of a prototypic hunting scene.

Fig. 46. Wild carnivore pursuing wild yak

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: flat back; straight tail, curled at end; upright ear; squared muzzle; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: It is not certain that these two figures constitute an integral composition. The carnivore exhibits a much lighter level of re-patination than the wild yak. The wild carnivore was retouched which seems to explain its current lighter coloration.

Fig. 47. Wild carnivore pursuing wild yak

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: flat back; straight tail, curled at end; upright ear; rounded muzzle; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 48. Wild carnivore (upper left), wild ungulate (upper right), wild caprid (lower right), and minor carvings

Taxa: probably feline

Prominent motifs: flat back; upward pointing tail, curled at end; upright ears; four flexed/unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Additional details: The wild carnivore and wild ungulate opposite it appear to form an integral composition. The wild carnivore does not seem to be in active pursuit of the wild ungulate. Other petroglyphs pictured probably belong to separate compositions.

Fig. 49. Wild caprid flanked by two other animals (upper) and wild carnivore pursuing wild ungulate (lower)

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; downward pointing tail, curled at end; upright ear; elongated muzzle; four flexed/unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Additional details: The wild ungulate (bottom right) appears to be a wild yak or deer. The identity of the two animals flanking the wild caprid (upper) is not clear. They may possibly be wild carnivores in the attack mode. All these figures appear to form an integral composition. Wild caprids and a wild yak made in the same time frame are found to the right of the figures illustrated.

Fig. 50. Wild carnivore pursuing wild ungulate with crescent moon and another wild ungulate above

Taxa: probably snow leopard

Prominent motifs: flat back; downward pointing tail, curled at end; upright ears; gaping mouth; two unflexed legs

Body: pecked, probably simulating spots

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: The two wild ungulates may possibly be depictions of wild yaks. The inclusion of the crescent moon may signify that this is a nocturnal hunting scene

Fig. 51. Carnivore pursuing wild yak with arrow embedded in its back

Taxa: probably feline

Prominent motifs: concave; tail overarching back, spiral at end; upright ears; gaping mouth; two unflexed legs with clawed feet

Body: pecked, probably simulating spots

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: The arrow in the back of the wild yak demonstrates that it is the prey of a human hunter, however, no archer is located on the same boulder (there is a group of other animal figures to the left carved in the same time frame). The spiraling tail, spots and clawed feet seem to identify the wild carnivore as a snow leopard or possibly a tiger. This may possibly be a prototypic hunting scene or one in which a wild carnivore serves as an ally of a human hunter.

Fig. 52. Wild carnivore (upper left), wild ungulate (upper right), wild caprid (lower right) superimposed on other carvings

Taxa: probably feline

Prominent motifs: flat back; upward pointing tail, curled in the middle; upright ears; four flexed/unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age Protohistoric period

Fig. 53. Wild carnivore attacking stag

Taxa: probably feline

Prominent motifs: double curved back; tail overarching back, curled at end; upright ears; rounded muzzle; four flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 54. Possible wild carnivore attacking wild yak

Taxa: possibly feline or canine

Prominent motifs: flat back; curling tail; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: It is not clear whether this is a predator attack scene.

Fig. 55. Wild carnivore attacking wild ungulate

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; downward pointing tail; upright ear; squared muzzle; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: lightly carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 56. Carnivore pursuing stag

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; straight tail; upright ears; gaping mouth; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: Found at bottom of stone panel which includes several other stags and wild yaks and hunter on horseback that appear to form an integral composition. If the carnivore is a wild variant, this may be an example of a prototypic hunting scene.

Fig. 57. Wild carnivore pursuing wild yak

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: flat back; upright ear; gaping mouth; two unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: lightly carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 58. Wild carnivore attacking wild yak from rear and bird above

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; downward pointing tail; upright ear; gaping mouth; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: lightly carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 59. Wild carnivore pursuing wild caprid

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; downward pointing tail; upright ear; pointed muzzle; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Additional details: For this image, also see the January 2014 (fig. 58) Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 60. Wild carnivore pursuing wild yak with wild caprid

Taxa: probably feline

Prominent motifs: flat back; S-shaped tail; gaping mouth; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Additional details: Several mounted archers hunting wild yaks and deer are situated above the figures on the same stone panel. These petroglyphs were made in the same time frame and appear to comprise an integral scene. The part of the composition pictured here may depict a prototypic hunting scene.

Fig. 61. Two wild carnivores pursuing wild caprid

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; downward pointing tail; upright ears; pointed muzzle; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Additional details: There is another wild carnivore to the right of the pictured figures that forms a separate composition. For a more encompassing image of this rock art, see the January 2014 (fig. 61) Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 62. Wild carnivore pursuing wild caprid (left), wild carnivore pursuing wild yak with another wild yak behind (center) and wild carnivore pursuing wild caprid (right)

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: concave/flat back; upward pointing tail, curled at end; upright ears; pointed muzzle; two unflexed/flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 63. Wild carnivore pursuing wild yak

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: flat back; upward pointing tail, curled at end; upright ears; pointed muzzle; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 64. Three carnivores and a horseman pursuing five or six wild yaks

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; downward pointing tail; upright ears; rounded muzzle/gaping mouth; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Additional details: The form of the carnivores matches others at the same rock art site without human figures (see figs. 19, 60, 62), suggesting that they are wild variants. If so, this may be a prototypic hunting scene. Also see the December 2013 (fig. 15) Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 65. Wild carnivore pursuing stag

Taxa: feline or canine

Prominent motifs: arched back; downward pointing tail; upright ears; squared muzzle; unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Early Historic period or Vestigial period

Group 5: Wild carnivores in ostensible ritual, mythic and symbolic scenes

Although the portraits and hunting scenes of wild carnivores illustrated above are, at least in some cases, are probably infused with mythic, ritualistic and symbolic significance, the outwardly mundane nature of the aspect and contents of these compositions veils their deeper significance. On the other hand, the compositions in this group more graphically capture remarkable cultural ideologies and activities. This is a highly diverse assortment of petroglyphs and pictographs, expanding the role of wild carnivores in the rock art of Upper Tibet.

Fig. 66. Wild carnivore and what appears to be an anthropomorph

Taxa: probably feline

Prominent motifs: concave back; tail overarching back, curled with ball at end; upright ears; pointed muzzle; four unflexed legs; male sexual organ

Body: outlined

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: To the right of the wild feline is what appears to be an anthropomorphic figure, arms and legs spread wide. Below this figure is another carving resembling a sunburst that is also an integral part of the composition.

Fig. 67. Wild carnivore and anthropomorph

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: arched back; tail overarching back, three curls; upright ears; gaping mouth; four flexed legs

Body: segmented vertically and horizontally, probably simulating stripes

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Additional details: The anthropomorph approaches the ostensible tiger with circular object in hand, in a demonstration of some form of relatedness with the animal. Also see the January 2014 (fig. 38) Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 68. Wild carnivore and two anthropomorphs that appear to form an integral composition

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: flat back; tail overarching back, spiral at end; upright ears; pointed muzzle; four flexed legs

Body: double volute motif

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: The tiger appears to be springing up in the direction of the two anthropomorphs but there is no indication of any defensive action on their part nor do the human figures appear to bear arms. The two anthropomorphs stand close together and are of different sizes, which may possibly indicate a male-female couple. The anthropomorph nearest the tiger appears to reach towards it with a triangular hand or object. The other anthropomorph extends its arm upwards terminating in the same type of triangular hand or object. For an image of the tiger, also see November 2014 (fig. 66) Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 69. Wild carnivore (below) and wild caprid (above)

Taxa: probably snow leopard

Prominent motifs: flat back; tail overarching back, spiral at end; upright ears; squared muzzle; four flexed legs with clawed feet

Body: pecked, probably simulating spots

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Additional details: Although the wild carnivore was carved in conjunction with the wild caprid, there is no intimation of danger in the composition. This suggests a more symbolic association between the two figures.

Fig. 70. Wild carnivore (below) and wild ungulate (middle) probably forming an integral composition, with another quadruped between them and another wild carnivore above forming separate compositions

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: double curved/flat back; tail overarching back, curled at end; upright ear; pointed muzzle; four unflexed legs

Body: lined, probably simulating stripes

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Additional details: The tiger and wild ungulate (probably deer or wild yak) are shown as independent portraits, perhaps symbolizing the prey-predator relationship in broader terms that may include ecological and/or cosmological associations. The upper tiger appears to have been made subsequently, using a sharper-edged cutting implement.

Fig. 71. Wild carnivore (middle), wild yak (lower) and deer (upper), with other anthropomorphs, zoomorphs and symbols that are part of the same composition (many are not pictured)

Taxa: probably tiger

Prominent motifs: concave back; S-shaped tail overarching back; upright ears; eye; gaping mouth; four flexed legs with clawed feet

Body: lined, probably simulating stripes

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Additional details: This integrated scene is extremely rich in cultural information. It was carved on a natural pillar of rock and the various figures are arrayed in conformance with a vertically aligned cosmological scheme (a well-known theme in the historical era). For more on this rock art, see August (figs. 13, 14) and November 2014 (fig. 51) Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 72. Wild carnivore and horned eagle

Taxa: canine or feline

Prominent motifs: concave back; upward pointing tail, spiral at end; upright ears; pointed muzzle; four flexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Additional details: The horned eagle, like the wild carnivore, is an extremely storied figure in Tibetan cultures. These two figures may possibly represent clan or tribal symbols or deities. Also see January 2012 (fig. 8) Flight of the Khyung; Bellezza 2008, p. 172 (fig. 303).

Fig. 73. Two confronted wild carnivores, female figure and another animal forming one or two integral compositions

Taxa: canine and/or feline

Prominent motifs: flat/double curved back; tail overarching back/downward pointing tail, curled at end; upright ear; gaping mouth/pointed muzzle; four/three flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Vestigial period

Additional details: The two wild carnivores seem to be prancing as if playing with one another. Perhaps the one on the left is a tiger and the one on the right is a lion. The animal below the pair, with its upright ears and pointed muzzle, may also possibly be a wild carnivore. The human figure wears a headdress not unlike those used traditionally by Tibetan women of high status. Also see Divine Dyads, pp. 199, 200 (bibliographic information in “Books” section of Tibetarchaeology.com). On traditional women’s headdresses of Upper Tibet, see October 2013 Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 74. Possible wild carnivore and counterclockwise swastika that may form an integral composition

Taxa: possibly canine and/or feline

Prominent motifs: concave back; downward pointing tail, forked at end; upright ears; squared muzzle; four flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Vestigial period

Additional details: The identity of the vertical extension below the head of the ostensible wild carnivore is unknown. There are numerous pictographs from the same time frame surrounding those pictured, complicating an assessment of compositional affinities. The swastika, a seminal Tibetan symbol, became a sectarian marker during the Early Historic period. The counterclockwise version is usually associated with non-Buddhist religious traditions. Also see Divine Dyads, p. 200.

The Origins of Horseback Riding in Mongolia: A review of a recent paper by Taylor et al.

This study reviews the following article: William Timothy Treal Taylor, Burentogtokh Jargalan, K. Bryce Lowry, Julia Clark, Tumurbaatar Tuvshinjargal, and Jamsranjav Bayarsaikhan. 2017. “A Bayesian chronology for early domestic horse use in the Eastern Steppe”, in Journal of Archaeological Science vol. 81, pp. 49–58. Elsevier.

The main aim of the Taylor et al. article is to pinpoint when horseback riding began on the Mongolian steppe. After reviewing the findings and conclusions of this work, its potential implications for the introduction of horseback riding in Tibet are considered.

Authors’ findings

The Taylor et al. article analyzes a large sample of radiocarbon dates obtained for horse remains unearthed by various archaeological expeditions in Mongolia. These horse bones belong to the Deer Stone-Khirigsuur (DSK) culture, consisting of sites with interrelated funerary mounds and stelae. Utilizing a Bayesian model of statistical inference, the authors provide a more reliable chronological range for series of radiocarbon dates. Their calculation of dating probabilities confirms that there was a rapid spread of horse ritualism in the eastern steppe associated with the DSK culture around 1200 BCE. However, it has not been determined if this cultural activity was associated with the introduction of the domestic horse in Mongolia or simply with the adoption of horseback riding.*

There has been very limited faunal analysis carried out for remains predating the DSK culture. Prior to the DSK culture in Mongolia, there may have been low frequency use of the domestic horse for traction (probably restricted to pulling chariots and/or carts). See William Timothy Treal Taylor. 2017. “The Origins of Horse Herding and Transport in the Eastern Steppe”, Ph.D. dissertation, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. The remains of a wooden cart have been found in a barrow labeled Khuurai-Gov’ No. 1, in Baian-Ölgii aimag (northwestern Mongolia), belonging to the Afanasievo cultural complex and dated to the end of the first half of the third millennium BCE. Only the bed of the vehicle was detected and it contained an array of burial goods. On this important discovery, see: Alexei A. Kovalev and Diimaazhav Erdenebaatar. 2009. “Discovery of New Cultures of the Bronze Age in Mongolia According to the Data Obtained by the International Central Asian Archaeological Expedition”, in Current Archaeological Research in Mongolia. Papers from the First International Conference on “Archaeological Research in Mongolia” held in Ulaanbaatar, August 19th–23rd, 2007” (ed. J. Bemmann et al.), pp. 149–170. Bonn Contributions to Asian Archaeology, vol. 4. Bonn: Vor- und Fruhgeschichtliche Archaologie Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat Bonn.

Also see: J. P. Mallory. 2010. “Bronze Age Languages of The Tarim Basin”, in Expedition, vol. 52 (no. 3), pp. 44–53. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. http://penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/52-3/mallory.pdf

This discovery of remnants of a wheeled vehicle indicates that animal traction first appeared in the region long before the rise of the pre-Scythic DSK culture. This is supported by an extensive body of petroglyphs depicting horse-drawn chariots in western and central Mongolia. Nonetheless, it is possible that some wheeled vehicles, like the one found in Khuurai-Gov’ No. 1 barrow, relied upon oxen for traction.

Although there is archaeological evidence suggesting that pastoralism in Mongolia may have originated as early as the third millennium BCE (after Eregzen 2016; Janz et al. 2017; Kovalev and Erdenebaatar 2010), Taylor et al. maintain that the introduction of horse riding facilitated herding by increasing the mobility and efficiency of herders. This coincided with the appearance of funerary stelae called deer stones in steppic regions of Mongolia, Tuva, northern Xinjiang and eastern Kazakhstan (after Bayarsaikhan 2016; Fitzhugh 2009; Volkov, 2002).* However, the authors note that this may possibly have occurred around one century after associated funerary mounds known as khirigsuurs were first constructed in Mongolia. They also observe that as the satellite features containing horse remains postdate the oldest khirigsuurs, horse ritualism appears to have been incorporated into a pre-existing cultural milieu, rather than spread through demic influx. The chronology of the khirigsuurs, however, is derived from radiocarbon analysis of human bones, and the authors rightfully caution that chronological biases resulting from significant freshwater dietary sources cannot be ruled out until a study of ancient and modern isotope signatures is conducted.

Calibrated radiocarbon dates for organic materials obtained from DSK sites in Kazakhstan, Tuva, Xinjiang, Kyrgyzstan, etc. are still lacking (W. Taylor, principal author of an article under review, in personal communication).

The builders of the DSK funerary monuments appear to have relied upon sheep, goats and cattle for their subsistence (after Clark, 2014; Houle, 2010), and dwelt exclusively in impermanent structures (after Allard et al. 2007; Houle, 2010). Charcoal and calcined bone fragments of sheep/goat and cattle and horse skeletal remains are regularly found on the periphery of DSK sites, attesting to sacrificial activities (Broderick et al. 2014). Regular patterns of horse skull deformation indicate that horses interred at DSK sites had been bridled and intensively used (after Taylor et al. 2015; Taylor 2016). Certain equine as well as human skeletal modifications are consistent with the adoption of horse riding (Taylor and Tuvshinjargal in press), although the use of the horse as a draft animal is also suggested by osteological analysis (Taylor 2017). The earliest metal horse tack, which was recovered from burials at Arzhan 1 and the Slab Grave culture, dates to the end of the DSK period, circa 800–700 BCE (after Fitzhugh 2009; Honeychurch et al. 2009).

The coming of draft horses to the central plains of China (after Kelekna 2009; Linduff 2003; Wu 2013) is concurrent with the appearance of horse sacrifices at DSK sites. Taylor et al. maintain that appearance of the domestic horse and chariots (two-wheeled vehicles) in China is linked to the expansion of horse ritualism and the erection of deer stones in Mongolia (cf. Honeychurch 2015; Shelach 2009). They state that improvements in horse transport leading to increased interaction with other groups probably prompted a geographically expanded ritual role for the horse. It is increasingly clear that augmented nomadic pastoralist networks dependent on horseback riding influenced patterns of trade and social interaction in Inner Asia (after Frachetti et al. 2017), and may well have facilitated the exchange of metals, ideas and artistic styles over a wide area of eastern Eurasia (after Honeychurch 2015). That major pan-cultural changes in the Late Bronze Age, not merely endogenous adaptation, are involved in the patterns of horse ritualism observed is supported by coeval dates for horse remains obtained from ‘shape burials’ in southern and eastern Mongolia, mortuary structures representing another archaeological culture (after Honeychurch 2015).

The findings of Taylor et al. suggest that Late Bronze Age cultural transformations associated with mobile pastoralism and horseback riding coincide with the aftermath of what may have been a prolonged drought in Mongolia and the diffusion of the horse more widely in East Asia. Citing studies that indicate an improving climate ca. 1500 BCE (after Feng et al., 2013; Propokenko et al., 2007; Wang et al. 2011), the authors believe that more productive grasslands may have provided ecological opportunities for herders to expand horse breeding and equestrian activities. This hypothesis contradicts an influential view that horse pastoralism in Mongolia was spurred on by deteriorating climatic conditions (after Khazanov 1984).

My comments

By more accurately plotting the age range of radiocarbon dates and drawing on key findings from other studies as well as their own evidence from the field and laboratory, the Taylor et al. article furnishes the best indication yet of when horse ritualism began in the eastern steppe. Their work highlights the need to better account for the absence of metal bridle components in Mongolia, prior to ca. 800 BCE. In part, this may be accomplished by more rigorous testing of a prevailing hypothesis, holding that only perishable bits and cheekpieces were used in the region prior to the ninth century BCE. To gain a clearer picture of the role of the horse in the mobile pastoralism of the eastern steppe, it is essential to determine if dated horse remains are related to the introduction of the domestic horse in Mongolia or just to the adoption of horseback riding. A significant conclusion of the Taylor et al. study is that favorable, not deleterious, climate change may have played a part in the development of horseback riding in Mongolia.

Of particular interest to Tibetan archaeology are the potential implications of the Taylor et al. study for understanding how the domestic horse, horseback riding and horse ritualism may have spread to the Tibetan Plateau. I have used collateral archaeological evidence from Upper Tibet to suggest that these various elements of horse use were introduced there in the early first millennium BCE, but any such assertion remains hypothetical.* Much of the archaeological evidence (monumental, rock art, artefactual) I have applied to an assessment of the origins of horse domestication, horseback riding and horse ritualism in Upper Tibet has not been securely dated. The uncertain chronology of the archaeological materials in question and the findings of the Taylor et al. study raise the prospect that horse use could possibly have reached the region somewhat earlier than the early first millennium BCE. Any such transfer to Upper Tibet of domestic horses, equestrian skills and technology, and the possible employment of horses in burial practices are predicated on rapid ideological and material exchanges of an intercultural and interregional nature.

This evidence is laid out in various works including the March 2016 and January 2017 Flight of the Khyung, as well as in my hard copy publications, including Antiquities of Upper Tibet (2002) and Zhang Zhung (2008). See the “Books” section of the website for bibliographic information.

The appearance of the domestic horse in the central plains of China in the 13th century BCE strongly suggests that pervasive exchanges of one kind or another permitted its rapid uptake in regions south and east of Mongolia. However, to postulate an equivalent network of equestrian transmission in regions to the south and west of Mongolia in the same period is more difficult to sustain with the archaeological data available. The earliest evidence for horse transport in southern Xinjiang includes copper alloy bits, but these do not appear to predate 1000 BCE.* Southern Xinjiang is of course geographically intermediate between the eastern steppe and Upper Tibet. Moreover, the possible transfer of chariot technology and vocabulary from the western steppe to Xinjiang and thence to China in the Late Bronze Age must be taken into consideration. The discovery of two wooden wheel hubs each with sockets for around sixteen wooden spokes at a site rich in cultural deposits known as Dalitaliha, on the Qinghai portion of the Tibetan Plateau, must also be weighed.† Unfortunately, artifacts recovered from this site have not been securely dated, and assignment on stylistic grounds to 1500 BCE or even earlier remains unverified. Any such west-east transmission of chariot technology fits well with the discovery of chariot petroglyphs in Upper Tibet, Ladakh and northern Pakistan.

See Mayke Wagner, Xinhua Wu, Pavel Tarasov, Ailijiang Aisha, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Michael Schultz, Tyede Schmidt-Schultzf, and Julia Greskya. 2011. “Radiocarbon-dated archaeological record of early first millennium B.C. mounted pastoralists in the Kunlun Mountains, China”, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, vol. 108 (no. 38), pp. 15733–15738. The authors of this study interpret copper alloy bits and bone cheekpieces recovered from the Liushiu cemetery as possibly belonging to highly valued riding horses. The location of these finds in summer pasturelands of the Kunlun mountains, around 2850 m in elevation, is more consistent with the use of mounted horses than with wheeled vehicles.

For a description of the Dalitaliha site, see Anthony J. Barbieri-Low. 2000. “Wheeled Vehicles in the Chinese Bronze Age (c. 2000–741 B.C.)”, in Sino-Platonic Papers (ed. V. H. Mair). Philadelphia: Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania.

http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp099_wheeled_vehicles_china.pdf

The presence of chariots pulled by equids in petroglyphs of Upper Tibet accords well with the concomitant transfer of this transport technology or knowledge thereof as part of the same vector of cultural and technological transference that brought them to Xinjiang and Qinghai. Thus, western avenues of transmission, not eastern steppe routes, may have first brought the domestic horse to Upper Tibet. Nonetheless, this is not incompatible with the introduction of horseback riding in Upper Tibet as possibly belonging to another sphere of ideological and technological influence, one in which Late Bronze Age Mongolia loomed large.

Systematic archeozoological research is required to determine when the introduction of the riding horse occurred in Upper Tibet. It is imperative that a firm chronology, comprehensive osteological profiling and molecular analyses of early horse remains and that of other animal domesticates is established for the region. This would greatly aid in more precisely gauging the position of Upper Tibet in the expanded flow of communications (with its cultural, economic, sociopolitical, and technological ramifications) permeating southern Xinjiang and the eastern steppes in the Late Bronze Age.

The Ancient Textiles of Upper Mustang: A review of a recent article on fabrics discovered in Samdzong

This work reviews the following article: Margarita Gleba, Ina Vanden Berghe and Mark Aldenderfer. 2016. “Textile technology in Nepal in the 5th-7th centuries CE: The case of Samdzong”, in STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research, vol. 2 (no. 1), pp. 25–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2015.1110421.

Authors’ findings

The landmark Gleba et al. article describes findings from an analysis of ancient textiles discovered in Samdzong, Upper Mustang. The scientific study of these fabrics and the dyes and pigment used to color them sheds light on technical, social and economic aspects of local textile production as well as on the long-distance exchange system to which Mustang belonged 1500 years ago.

Both scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission light microscopy (TLM) were employed to identify both wool and silk fibers in Samdzong burial textiles. The authors note that as no evidence of sericulture is known in the region, the silks must have come to Mustang from the northeast through long-distance trade. Organic dyes, including Indian lac, munjeet, turmeric, and knotweed/indigo, were identified through high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. Cinnabar exploited as a textile pigment was detected using micro-Raman spectrometry.

The textiles (all from animal sources) were discovered in shaft tombs dating to 400–650 CE (see June 2017 Flight of the Khyung). These textiles were relatively well preserved due to the arid climate and high elevation of the site and because of mineralization caused by contact with metal objects. Among objects found in tomb complex Samdzong 5 (constructed ca. 500 CE) was a bunch of woolen fabric with glass and knotted textile beads and copper tubules attached. The authors report that these fragments probably belonged to an elaborate headgear, which may have been attached to an anthropomorphic mask made of gold and silver found in the same tomb (see November 2013 Flight of the Khyung). The authors suggest that this textile object is made from sheep wool and horse hair, however, the fiber surfaces were too degraded for accurate species identification.

Gleba et al. describe the Samdzong burial, characterizing it as “elite” in nature, because of the wide range of grave goods it contained, including two large copper vessels and a ladle, iron daggers, wooden and bamboo cups and trays, copper and bronze bangles, and thousands of glass beads (as well as a wooden coffin and the burial mask). Chemical and technological analyses of the metals indicate that they were fabricated on the Tibetan Plateau or Indian Subcontinent (after Massa 2013), while the glass beads originated in Central Asia, Sassania and the Indian Subcontinent (after Dusseubieux 2015).

My comments

Although ancient Han China or areas to its northwest such as Gansu, Shaanxi or Xinjiang were the likely sources for silks discovered in Samdzong, intermediate regions and agents were required to transfer them to the southern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. This probably entailed passage across the Tibetan Plateau beginning in highland Gansu-Qinghai (A-mdo) or in Ruthok (Ru-thog). Archaeological evidence, particularly from the rock art record, indicates that these regions functioned as northeast and northwest gateways respectively for a host of artistic and material inputs to the Tibetan Plateau beginning in the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age. Little is known about the routes trans-plateau exchange might have taken in prehistory, but the penultimate geographic node of transmission must have been the Upper Tsangpo river valley, which lies immediately north of Upper Mustang.*

On trade and exchange networks in Upper Tibet, also see “A Review of a Recent Scientific Article: “Earliest tea as evidence for one branch of the Silk Road across the Tibetan Plateau”, in April 2016 Flight of the Khyung.

Generally, the border between Upper Tibet and Nepal is punctuated by difficult high-elevation glaciated passes. However, the Kali Gandaki valley effectively breaches the Great Himalayan range, creating relatively easy access between Upper Mustang and the Upper Tsangpo (Mar-tshang gtsang-po) valley. That area of Upper Tibet (Stod) was traditionally part of a district known as Drongpa Tshogu (’Brong-pa tsho-dgu).

Fig. 1. Silk tabby, now brownish and reddish in color, and a darker colored woolen fabric below. From a Gurgyam shaft tomb. Gurgyam monastery museum. Photographed in 2010.

Fig. 2. A mass of gauzy silk from the Gurgyam shaft tomb. Gurgyam monastery museum. Photographed in 2010.

The two open tabby silks fabrics analyzed and pictured in Gleba et al. (samples 50, S13), in weaving style and coloration (presently brown and reddish brown), can be compared to silks recovered from a shaft tomb at the Gurgyam site, situated 400 km to the northwest.* Nevertheless, scientific analysis is required to determine how closely related technical features of the silk fabrics found in Samdzong and Gurgyam actually are. The burial at Gurgyam has been radiocarbon dated to 220-350 CE, making it 150 to 300 years older than Samdzong 5. Even more ancient textiles woven from cotton and other plant fibers and animal fibers were discovered in burials of Mebrak (400 BCE to 50 CE), in Mustang.† Unfortunately, these fabrics were not as thoroughly analyzed as those in the Gleba et al. study, impeding comparative analysis.‡

A large variety of grave goods were obtained from this burial including a spectacular patterned silk. For a preliminary report of these finds, including radiocarbon analysis, see October 2010 Flight of the Khyung.

See Kurt W. Alt, Joachim Burger, Angela Simons, Werner Schön, Gisela Grupec, Susanne Hummeld, Birgit Grosskopf, Werner Vach, Carlos Buitrago Téllez, Christian-Herbert Fischer, Susan Möller-Wiering, Sukra S. Shrestha, Sandra L. Pichler, Angela von den Driesch. 2003. “Climbing into the past – first Himalayan mummies discovered in Nepal”, in Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 30, pp. 1529–1535.

http://www.uni-mainz.de/FB/Biologie/Anthropologie/Nepal_Mumien.pdf

What is described a woolen blanket fragment was excavated In Tsamda (Rtsa-mda’) county, Guge, by Chinese archaeologists. This flat weave is dyed red, yellow and light blue and has stripes and other designs including a row of hexagonal geometric forms with hourglass motifs in the middle of each one. This textile is said to have come to the region through trade (but no evidence supporting this opinion is given). Another woolen patterned flat weave fragment excavated by the Chinese in Tsamda county consists of intricately designed geometric patterns (rows of triangles, stripes joined by series of parallel lines and other geometric forms) in an undyed white wool set against what appears to be a natural chocolate brown and medium blue ground. There is also a row of wild ungulates woven into the ground. For color images and brief descriptions of these textiles, see pp. 219, (fig. 131), 220, 221 (fig. 132) of Zla-ba tshe-ring, Suo Wenqing, dBang-vdus, bSod-nams dbang-vdan. 2000. Precious Deposits: Historical Relics of Tibet China. Beijing: Morning Glory Publishers. The geometric and zoomorphic subjects on the latter woolen fragment positively identify it as Upper Tibet in origin. Even today (although the use of handspun wool has fallen out of favor), the same kinds of designs are woven by pastoralists on sashes, saddlebags and food sacks. Unfortunately, no chronological information on these two textiles is provided in Zla-ba tshe-ring et al. It appears that the red, yellow and light blue specimen is ancient and comparable to textiles originating in Xinjiang and northwestern China. It may possibly date to the early centuries of the Common Era. As the other woolen fragment belongs to a weaving tradition still practiced today, little can be said about its age from the photograph provided.

Drongpa Tshogu acting as a proximate node in a wider system of exchange extending to Upper Mustang is suggested by the discovery of silk fabrics in southwestern Tibet. Although information about the textiles found in Gurgyam is still scant,* it is possible to consider how these fabrics and those from Samdzong may have circulated widely. We now know that, from no later than the third or fourth century CE to at least the sixth century CE, similar types of silks were used in burial rites on the Western Tibetan Plateau (comprised of Upper Tibet and adjoining plateau areas to the south and west). The upper reaches of the Tsangpo river have long served as a conduit between Upper Mustang and southwestern Tibet, potentially linking both regions to the same trans-regional exchange network that stretched to silk-producing centers north and east of the Tibetan Plateau. The major historical route through the Upper Tsangpo valley was known as the Rgya-lam (much of it ran through collateral valleys, as it does today, crossing a string of smaller passes). This route facilitated exchanges of many kinds in the second millennium CE, but earlier usage is indicated by the occurrence of the same set of pre-Buddhist (pre-7th century CE) monuments along the upper course of the river (all-stone corbelled fortresses and temples and stelar necropolises, etc.; see www.thlib.org/bellezza).

A study of the various Gurgyam burials excavated by Chinese archaeologists in recent years is expected to be released soon in China by Tong Tao et al.

In addition to silks, potentially a variety of other tribute payments, diplomatic gifts, prestige goods and trade items may have been part of a system of exchange encompassing the Western Tibetan Plateau in the first half of the first millennium CE. For instance, salt, borax, gold potentially moved south to Upper Mustang (and the Indian Subcontinent), while various botanicals, musk and agricultural products could have traveled northward to Upper Tibet. Objects made from cane and bamboo found in tombs of Gurgyam and further north in Guge almost certainly came from cis-Himalayan regions.

Fig. 3. Fragmentary strings of glass beads found in the shaft tomb at Gurgyam, which also contained an array of silk and wool textiles (burial dated to ca. 220–350 CE). Many such strings of beads were recovered from this tomb. They are now housed in a local museum. Unfortunately, this image (taken in 2013) is out of focus.

Moreover, like the silks, the presence of comparable turquoise-colored, wheel-shaped glass beads in the burials of both Gurgyam and Samdzong, which were produced much farther afield, indicate a significant shared material dimension in the funerary rites of the two locations (fig. 3).* Glass beads, depending on their origins, may have entered the Tibetan Plateau from various directions. The spread of silk and glass beads and other exotic goods to the Western Tibetan Plateau represents a ramified exchange network based on larger spheres of geographic dissemination. Other objects indicative of this scaling up of exchange links include carnelian and patterned agate beads and cowrie shells (see May 2014 and January 2016 Flight of the Khyung). This system of exchange, in one form or another, appears to have operated for at least two or three centuries. The interchange of this period set the tone for or at least opened the way to interregional communications of the historical era.

For a photograph of similar glass beads and other types of beads collected from the Khardong (Mkhar-gdong) fortress site, located just 2 km from Gurgyam, see April 2012 (fig. 14) Flight of the Khyung.

Next month: The history of Upper Tibet according to its rock inscriptions!