October 2016

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to Flight of the Khyung, your journey to the mysteries of ancient Tibet! This month’s newsletter boasts an article about recent archaeological discoveries in Ladakh, written by Dr. Quentin Devers et al. This work breaks new ground by tackling thorny historical problems that have long plagued the study of Ladakh. It paves the way to a clearer understanding of the political, cultural and historical complexion of Western Ladakh in the 11th century CE. In doing so, this article presents valuable sources of evidence (rock art, inscriptions, fortresses) for the first time, prying open a vista on the past with crucial implications for subsequent research.

The second and final article in this month’s newsletter details the discovery of mask-like objects carved on boulders in Spiti. These carvings may help push back cultural links between Spiti, Upper Tibet and Ladakh to the Bronze Age.

The Petroglyphs of Kharool: The New Alchi of Ladakh

Written by Quentin DEVERS, Nils MARTIN, KACHO Mumtaz KHAN, Tashi LDAWA

Introduction

![Fig. 1. Location of Kharool and other sites in Ladakh. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig01-e1478639919717.jpg)

Fig. 1. Location of Kharool and other sites in Ladakh. [Q. Devers]

The petroglyphs of Kharool were partially surveyed by Tashi Ldawa in 2007. After this initial documentation, no other scholars took an interest in the site. The search for Kharool was set in motion again by Nils Martin in the Spring of 2016. He noticed that in the temple inscription of the Nyima Lhakhang, in Mulbek, the ruler of Phokhar is reported to have received many villages from the ruler of Kashmir, “and even the fortress of Kharyul”. Looking for this location on a map, Martin noticed a village called Kharool near Kargil, at the confluence of the Dras and Suru rivers. Given the particulars of the name, Quentin Devers went there searching for a fortification in the summer of 2016, during a survey conducted in collaboration with Kacho Mumtaz Khan and funded by INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage). A fort was indeed located at the very confluence of the two rivers. Opposite the fortress are the fields and handful of houses of Kharool, among which are carved boulders. The following description is based on several subsequent visits to the site by the authors, with the invaluable help of Kacho Sikundar Khan and Hassan Khan.

Archaeological environment of the site

![Fig. 2. Plan of Kharool with the main zones of engravings. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig02-e1478640083772.jpg)

Fig. 2. Plan of Kharool with the main zones of engravings. [Q. Devers]

In former times, the regular route to Skardu from Kargil crossed the Dras river at Kharool and continued downstream along the left bank of the Suru (Fig. 2). A few kilometers from the confluence that path crossed a small plateau known as Serthang, or ‘Gold Plain‘, where a gold mine is believed to have existed. Many dark boulders are located along this route, including some that are most probably carved. This area, however, is very close to the line of control and is believed to be scattered with unexploded ordinance. Extra precautions are needed to access Serthang, which the authors will implement during a planned survey in 2017.

![Fig. 3. General view of Kharool from the North. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig03-e1478640129810.jpg)

Fig. 3. General view of Kharool from the North. [Q. Devers]

Overview of the carvings

![Fig. 4. Examples of zoomorphs at Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig04-1024x385.jpg)

Fig. 4. Examples of zoomorphs at Kharool. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 5. Examples of anthropomorphs at Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig05-1024x385.jpg)

Fig. 5. Examples of anthropomorphs at Kharool. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 6. Examples of flowers at Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig06-e1478640363706.jpg)

Fig. 6. Examples of flowers at Kharool. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 7. Group consisting of a lion, horse and tiger at Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig07-e1478640386314.jpg)

Fig. 7. Group consisting of a lion, horse and tiger at Kharool. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 8: Detail of the lion, horse and tiger in Fig. 7. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig08-1024x385.jpg)

Fig. 8: Detail of the lion, horse and tiger in Fig. 7. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 9: The two other lions of Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig09-1024x385.jpg)

Fig. 9: The two other lions of Kharool. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 10. Patches of circles at Kharool. [T. Ldawa]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig10-1024x384.jpg)

Fig. 10. Patches of circles at Kharool. [T. Ldawa]

![Fig. 11. Example of compartmented shapes at Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig11-e1478640506334.jpg)

Fig. 11. Example of compartmented shapes at Kharool. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 12. The two handprints of Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig12-1024x586.jpg)

Fig. 12. The two handprints of Kharool. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 13. Examples of chortens at Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig13-837x1024.jpg)

Fig. 13. Examples of chortens at Kharool. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 14. Trio of a different type of chortens, Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig14-e1478640603889.jpg)

Fig. 14. Trio of a different type of chortens, Kharool. [Q. Devers]

Fig. 15. Example of chortens in Northern Pakistan. Source: Pamirtimes.net (http://pamirtimes.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Archeological-Carvings-at-Chilas-Diamer-3.jpg)

Of critical inscriptions, or how to open a new page of history

![Fig. 16: Tibetan inscriptions at Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig16-e1478640653822.jpg)

Fig. 16: Tibetan inscriptions at Kharool. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 17: Other inscriptions at Kharool: in Kharoshti (?) on the left, in Sarada (?) on the right. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig17-1024x385.jpg)

Fig. 17: Other inscriptions at Kharool: in Kharoshti (?) on the left, in Sarada (?) on the right. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 18: Boulder with the main inscription, Kharool, with Kacho Sikundar Khan (right) and Hassan Khan (left). [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig18-e1478640715120.jpg)

Fig. 18: Boulder with the main inscription, Kharool, with Kacho Sikundar Khan (right) and Hassan Khan (left). [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 19: Closer view of the two parts of the main inscription, Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig19-e1478640735470.jpg)

Fig. 19: Closer view of the two parts of the main inscription, Kharool. [Q. Devers]

The first lines of both parts of the inscription give us the most crucial information of all dedicatory inscriptions at this western group of sites. The first line of part A commemorates an event that took place in a dragon year, while the first line of part B mentions the king of Purang Od De (’Od lde, 1024–1037). There is only one dragon year under this ruler: 1028, which thus seems a likely date for the inscription or the events to which it gives account.

Some of the soldiers stationed in Kharool seem to have also been in Alchi and Khaltse. These three sites form a coherent ensemble with similar types of locations, similar archaeological environments, similar types of chorten engravings, and similar individual and clan names in the inscriptions. They differ on several of these points from other chorten carvings and Tibetan inscriptions found in Northern Pakistan and in Nubra. The sites in these three areas form three distinct groups that cannot be directly linked, and which are probably the result of different historical events.

Focusing now on Western Ladakh only, the main inscription at Kharool clears doubts about the origin of the carvings at Alchi, Khaltse and Kharool: they pertain to some type of a Western Tibetan military force that campaigned in the early 11th century in Western Ladakh; they do not appear to relate to the Tibetan empire. Some individual carvings may not belong exactly to this precise conquest but to later events, the Bro and the Smer clans being still attested respectively in Alchi and Mangyu a century later or so (Martin 2016). But no elements in these sites demonstrate an intelligible link with the Tibetan Empire: the earliest tangible element at our disposal is an early 11th-century military campaign by Od De.

Bruzha and border areas

Part B of the inscription further mentions Bruzha, the first attested reference to this region in an inscription in Ladakh. It should be pointed out here that Kharool, by its very geographical location, is a natural candidate to play a border role between Ladakh, Northern Pakistan (Baltistan, Gilgit) and even Kashmir. The hamlet is located at the confluence of the Suru and Dras rivers. In former times, the regular route from Kargil to Skardu crossed the Dras brook at Kharool and then followed the Suru on the left bank towards the Indus. The area around Kharool has for a long time represented a frontier between Purig and Baltistan, and still does. The line of control used to be on the mountain above the village, and is now only a few kilometers away.

As noted, Kharool (under the name Kharyul) is mentioned in a temple inscription inside the 14th to 15th century Nyima Lhakhang in Mulbek. The ruler of Phokhar is said to have received many villages from the ruler of Kashmir, “and even the fortress of Kharyul”, suggesting that it previously belonged to the latter. A Kashmiri domination of the valley of Dras during some parts of Ladakh history is not strange, especially considering the material evidence seen in Dras. Fortifications there follow layouts that are atypical for Ladakh, and inside there are potsherds of wheeled ceramics (a technique absent from Ladakh). Furthermore, the famous Buddhist carvings of the village are the only ones in Ladakh to be inscribed in Sarada instead of Tibetan. Thus, it is increasingly evident that Kharool may have been under Kashmiri influence at times. As such, in addition to being a border village between Purig and Baltistan, Kharool might also have been a border village between Purig and Kashmir. That it is in Kharool where we find one of the longest military rock inscriptions in Ladakh referring to Bruzha is sound from a military point of view: Kharool was a strategic place right at the doorstep of Bruzha.

Historical and geographical wider context

The types of chorten engravings and dedicatory inscriptions at Kharool are not only found at Alchi, Khaltse, Balukhar and Kharool. Other sites with similar petroglyphs and inscriptions are situated primarily along the Indus valley (near Narmo, Domkhar and Lehdo) and in Purig (near Paskyum, Yarchok and Namsuru). Undoubtedly, more are yet to be found. All sites of this type have the same geographical context: they were crossing points over important rivers and located away from villages. However, surveys conducted by Quentin Devers and Kacho Mumtaz Khan in Purig revealed a second type of location: in Namsuru and in Yarchok (Kartse Khar valley), the carvings are found high up on mountainsides. These two sites offer great vantage points, ideal observation posts for watching armies coming from afar. As such, the shared characteristics between these two types of locations are as strategic places (river crossings, lookout posts) situated away from populated centers. No such inscriptions are found near ancient military installations located inside villages, only at those situated in uninhabited spaces.

An important consideration is that no such sites are found in Upper Ladakh. All the inscriptions are located downstream of the confluence of the Indus and Zanskar rivers. This geographical layout is very interesting for us. As Devers explained elsewhere (Devers 2016), there is ever more evidence for significant material differentiation between Upper/Eastern and Lower/Western Ladakh. The former region displays links with Western Tibet, whereas the latter shows influence from Northern Pakistan (Baltistan and Gilgit areas). The border between the two regions appears to have resided at the confluence of the Indus and Zanskar rivers, which was also found to be a linguistic divide by Zeisler (Zeisler 2013).

It is commonly thought that Nyimagon (Nyi ma mgon) received Maryul from the hands of the Gyapa Jo (Rgya pa jo) or, alternatively, that he conquered it. There have been long debates as to what the name Maryul designated before the rise of the Western Tibetan dynasty. In the context of the annexation of the region by Nyimagon and considering the material remains found in Eastern and Western Ladakh, it appears that Nyimagon-controlled Maryul meant Eastern Ladakh only, i.e. the area extending from the Indus/Zanskar confluence eastwards/upwards, in the direction of Tibet. Western Ladakh does not appear to contain archaeological remains connected to the incorporation of Maryul into the possessions of the Western Tibetan kingdom by Nyimagon in the 10th century, nor do any of its villages seem to appear in historical texts belonging to that period.

The most characteristic and earliest material remains pertaining to the Nyimagon dynasty in Ladakh are rock inscriptions at various sites, which can now be dated to around the reign of king Od De in the 11th century. He was known for being a fighter at heart and to have campaigned in the land of Bruzha and other regions (Vitali 1996: 115). The military inscriptions left by his armies are situated all the way from Alchi, the first strategic crossing point found after the Indus/Zanskar confluence, to Baltistan and Kashmir, along the Indus river and in Purig. The areas where the inscriptions have been discovered all exhibit antecedent material influence from Northern Pakistan, suggesting they were not part of the same Maryul as Eastern Ladakh. At that time, they may very well have represented a foreign land that either belonged to or was in the sphere of influence of Skardu and Gilgit.

What we have here seems to be evidence for a large-scale assault on Western Ladakh by the armies of Od De. We do not find inscriptions in Eastern Ladakh, a region that already belonged to Western Tibet. The first inscriptions are found only soon after the Indus/Zanskar confluence, in Alchi. We have the same names of soldiers in several locations: the same army was marching west towards Bruzha. And right at Kharool, a strategic location at the doorstep of the latter, we find an inscription referring to this land, the only such mention known in Ladakh.

It is probably at that time when Western Ladakh became part of the dominions of the Western Tibetan kingdom. It is unclear whether this conquest was long-lasting or if these new parts were quickly lost. This will be the object of another paper by Nils Martin concerning the temple inscriptions at Alchi and Mangyu, where he will present new information that enable us to build upon this reconstruction of the early phases of historical Maryul.

On the limitations of patina and style- or motif-based dating

![Fig. 20: The animal trio (left) and a Tibetan inscription with a chorten (right) carved on the same boulder. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig20-e1478640767861.jpg)

Fig. 20: The animal trio (left) and a Tibetan inscription with a chorten (right) carved on the same boulder. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 21: Chorten with varying patina, Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig21-e1478640792532.jpg)

Fig. 21: Chorten with varying patina, Kharool. [Q. Devers]

![Fig. 22: Detail of the varying patina on the lower part of the chorten, Kharool. [Q. Devers]](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Fig22-e1478640818618.jpg)

Fig. 22: Detail of the varying patina on the lower part of the chorten, Kharool. [Q. Devers]

Finally, concerning motif-based analysis, we saw earlier the case of the two handprints associated with chorten engravings (Fig. 12). Although handprints are usually considered to be from prehistory, nothing in the site of Kharool reveals a prehistoric context – the only tangible elements are historic. These are further reminders that motif-based dating also has serious limitations and cannot be applied all the time.

These are only a few examples, but many more cases can be seen across Ladakh. A chronological analysis should not rely too heavily on patina, style and motif interpretation. Though these are useful tools that probably work in many instances, they cannot be applied on individual carvings without taking in account other factors such as the historical, archaeological and land use contexts of each petroglyph site. Ladakh is a region with much cultural, religious and ethnic complexity, where only careful contextualization can help differentiate between what could be simple cultural or regional variations instead of strict chronological differences. A necessary step towards better rock art analysis will require a better understanding of the various contexts, in order to more accurately assess the environment in which they were created and, in turn, to better understand the carvings themselves and their dating.

Conclusion

Kharool represents one of the most important petroglyph sites in Ladakh. It is situated at a strategic confluence and crossing, only minutes away from Kargil, at the verge of Ladakh, Baltistan and Kashmir. It belongs to a group of similar sites found at strategic military locations (river crossings and observation posts), away from villages, where soldiers engraved chortens on boulders, some with dedicatory inscriptions. Similar types of chortens and names are found near the military sites of Alchi, Khaltse and Balukhar. They form a coherent ensemble that differs from the types of locations, archaeological environments, names and chortens found in neighboring areas such as Northern Pakistan and Nubra. The main inscription at Kharool, one of the longest for this period in Ladakh, settles an old debate about the dating of this group of inscriptions in Western Ladakh. They are not related to the Tibetan empire, but to the Western Tibetan kingdom. We have at Kharool an inscription written in the reign of Od De in 1028, a ruler known for his military activities. All sites with similar inscriptions are located downstream of the Indus-Zanskar confluence. This military presence concerns Western Ladakh only, showing a clear differentiation of the region from Eastern Ladakh, which allegedly already belonged to Western Tibet.

The main inscription at KharooI opens a new chapter in the history of the early phase of Maryul as part of the Western Tibetan kingdom. A detailed reading and translation of inscriptions found in Western Ladakh will be provided in an article under preparation by Nils Martin and Quentin Devers. The aftermath of the conquest by Od De will further be covered in another article by Nils Martin, based on a new reading of the temple inscriptions of Mangyu and Alchi. Finally, a series of forthcoming short papers in Flight of the Khyung will introduce other new rock art sites, which, like Kharool, contribute to an improved understanding of the early history of Ladakh.

References

Devers, Quentin, 2016, Archaeological Ladakh, a contribution of recent discoveries to redefining the history of a key region between the Pamirs and the Himalayas, 14th colloquium of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, 20th of June.

Kaul, S. and Kaul, H. N. 1992: Ladakh Through the Ages, Towards a New Identity, Delhi: Indus Publishing Company.

Martin, Nils, 2016: The lDe, the ’Bro, and the sMer, inscriptional evidence from the temple of Avalokiteshvara at Mangyu, 14th colloquium of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, 20th of June.

Vitali, Roberto, 1996: The kingdoms of Gu-ge Pu-hrang: according to Mgnaʾ-ris rgyal rabs by Gu-ge Mkhan-chen Ngag-dbang-grags pa, Dharamsala, Tho ling gtsug lag khang lo gcig stong ’khor ba’i rjes dran mdzad sgo’i go sgrig tshogs chung

Zeisler, Bettina, 2013: The dialect groups of Upper and Lower Ladakh. Apparent and less apparent differences, 16th colloquium of the International Association for Ladakh Studies, 17-20 April.

About the authors

Quentin DEVERS is a researcher at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (Paris). He works on the archaeological remains of Ladakh, with a focus on fortifications, temple ruins and pre-Buddhist funerary sites.

Nils MARTIN is a PhD candidate at the École Pratique des Hautes Études (Paris), where he is preparing a dissertation about the murals of Ladakh from the 14th and 15th century, co-supervised by Charles RAMBLE (Directeur d’études, EPHE, Paris) and Christian LUCZANITS (Professor, SOAS, London). He also takes a close interest in the early Tibetan inscriptions of the region.

KACHO Mumtaz KHAN works on the inventory and protection of the heritage of Ladakh. He is most active in the district of Kargil, where he has conducted projects on important sites such as the large Chamba of Apati. He is co-convenor of the Ladakh chapter of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH).

Tashi LDAWA is professor of zoology at the Leh Degree College. He has surveyed the rock art of Ladakh since 1997. He has dedicated himself to raising awareness and conserving this rich heritage through the organization of exhibitions, workshops and the creation of pedagogic material.

Discovery of Three Mascoid Carvings on a Boulder in Spiti

In the Spring and Summer of 2016, six more rock art sites were documented in Spiti, bringing the total number in this region of Himachal Pradesh to at least thirty-three. These discoveries were made by the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society, a local organization committed to protecting the rapidly dwindling ancient cultural heritage of Spiti. As of 2016, over 1900 boulders with rock art have been registered in Spiti and Sumra (a locale in Kinnaur on the Spiti river opposite Lower Spiti).

Spiti, a region making up half the district of Lahaul-Spiti, shares a long border with Tibet and Ladakh. Indeed, the rock art of Spiti has much in common thematically and stylistically with western Tibet and Ladakh (for a survey of Spitian rock art, see the July to November 2015 issues of Flight of the Khyung).

Among the most important rock art finds in 2016 were made near the settlement of Hurling (Lower Spiti, more than 95% of all rock art in Spiti is in this area). Here three mascoids (anthropomorphic visages in emblematic form) were discovered on a single border. In diverse forms, mascoids are also seen in the rock art of southern Siberia, the Altai, Ningxia, northern Pakistan, northwestern Tibet, and Ladakh.* The identity and function of mascoid rock art is still very much in question. Its use and symbolism may have varied considerably from region to region and culture to culture. We simply do not know. Certainly, they were of sufficient importance to be adopted by a variety of ancient peoples in Inner Asia, transcending sundry cultural, ethnic and linguistic barriers. Mascoids are often dated by rock art specialists using non-direct means to the Bronze Age (ca. 2000–1000 BCE). Estimates of age assigned to them have not yet been scientifically corroborated.

* For comparative studies of mascoids focusing upon specimens from Upper Tibet and Ladakh, see the following works:

December 2011 Flight of the Khyung.

Bellezza, J. V. 2014: The Dawn of Tibet: The Ancient Civilization on the Roof of the World. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bruneau, L. 2010: “Le Ladakh (état de Jammu et Cachemire, Inde) de l’Âge du Bronze à l’introduction du Bouddhisme : une étude de l’art rupestre, vols. 1, 2, 3. Répertoire des pétroglyphes du Ladakh”. Ph.D. dissertation, Université Paris I-Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Bruneau, L. and Bellezza, J. V. 2013: “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’” in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28, pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS (http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf).

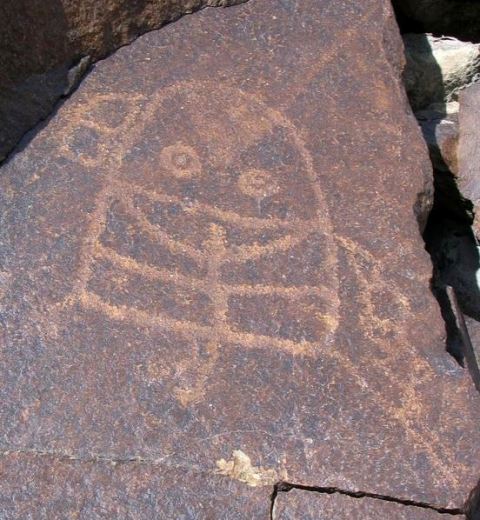

Fig. 1. Three mascoids on a boulder near Hurling, Spiti. The upper two specimens are partially cut in the photograph. Cross-cultural indications suggest that these mascoids may date to the Bronze Age. Also on the boulder is a handprint and several curvilinear and rectilinear subjects of unknown identity. All these carvings appear to be of significant antiquity. Photograph courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

Fig. 2. Two of the mascoids and handprint in fig. 1 (lower half of image). Above the mascoids is a spiral and other carvings. Photograph courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

The mascoids of Spiti include two rectangular specimens with slightly pinched sides subdivided into two sections. The interior of both parts of these mascoids contain minor carved areas. The third mascoid discovered in Spiti has a semicircular outline and is also divided into two parts. A carved blotch cutting across the top of the mascoid does not appear to be an original artistic feature. Each of the two sections of this bell-shaped mascoid contains two circles with a dot in the middle (the lower right circle and dot form a spiral).

Of equivalent age to the mascoids is a carving of a handprint with five fingers plus an opposable thumb. It is situated next to the semicircular mascoid. The matching carving technique used to produce the handprint and mascoid and the uniform wear of the carvings suggest that they may possibly form an integral composition, the handiwork of a single artist, but this cannot be confirmed from a visual appraisal alone. Handprints attributed to the Bronze Age have been documented in the rock art of Ladakh and north Inner Asia. There are also handprints in these regions belonging to more recent periods. Handprint rock art is very rare in Upper Tibet.

The discovery of mascoids in Spiti augments the range of rock art subjects aligning Spiti with Upper Tibet and Ladakh. Other cognate subjects of the Western Tibetan Plateau (WTP) include felines in the Eurasian animal style, horned eagles, tiered shrines, wild yak hunting on horseback, and cosmological symbols. These kinds of subjects reflect the existence of cultural and artistic interconnections between Spiti, Upper Tibet and Ladakh in the Iron Age (ca. 600–100 BCE), Protohistoric period (ca. 100 BCE to 600 CE) and Early Historic period (ca. 600–1000 CE). Nevertheless, the mascoids of Spiti may possibly be the oldest examples of rock art also common to Upper Tibet and Ladakh. Although a Bronze Age attribution for the earliest mascoids of the Western Tibetan Plateau is provisional, it is supported by the extreme erosion and re-patination exhibited by them.

Also of potential Bronze Age antiquity on the Western Tibetan Plateau (WTP) is bronze metallurgy, chariot carvings, mortuary pillars and agricultural remains. In tandem with mascoid carvings, this physical evidence seems to root communications between the constituent parts of the WTP in a highly remote period, serving as a precedent for later cultural and demographic interactions in the region. More crucially, the widespread distribution of mascoids in Inner Asia suggests that the WTP was privy to broad interregional exchanges occurring as early as the Bronze Age. These appear to have impacted Spiti, Upper Tibet and Ladakh in fundamental but still not well understood, ways.

The mascoids of Spiti are most comparable to those in Upper Tibet and Ladakh. As with horned eagles, wild yak hunting on horseback and other cardinal subjects and themes, it is Spiti’s larger eastern and northern neighbors that probably served as inspiration for the creation of the mascoids. Around fifty mascoids in several major styles have been documented in northwestern Tibet and around 100 in Ladakh (most come from the Murgi Tokpo site in the Nubra valley), hinting that their cultural center of gravity lay in those directions. However, the mascoids of Spiti are not identical to Upper Tibetan and Ladakh variants, rather they are unique expressions of an emblem or symbol with much wider currency. The Spitian examples are decidedly simpler in form than their Upper Tibetan and Ladakh counterparts, which also suggests that they are derivative or imitative in nature.

Fig. 3. Bell-shaped mascoid, Murgi Tokpo, Ladakh. This mascoid has a symmetrical array of internal elements, a characteristic trait of mascoid rock art on the WTP and other regions of Inner Asia. In addition to two ‘eyes’, the upper half of the carving has a triangular head adornment or hairline. The bottom half of the mascoid is partitioned into two parts, each with an inward pointing triangle. Photograph courtesy of Laurianne Bruneau.

Fig. 4. Bell-shaped mascoid with eyes, other internal elements, feet and wielding what appears to be a bow, Murgi Tokpo, Ladakh. Photograph courtesy of Laurianne Bruneau.

Fig. 5. Mascoid with sub-rectangular outline divided into two halves, each adorned with two spirals, Ruthok, Upper Tibet.

Fig. 6. Rectangular mascoid with slightly pinched sides divided by a line into two halves, Ruthok, Upper Tibet. This example, while very close in form to Spitian mascoids, probably dates to a later period. I refer to such types as pseudo-mascoids. Some of them bear complex internal elements. Pseudo-mascoids appear to have been produced in the Iron Age and Protohistoric period.

The bell shape of Spiti’s most complex mascoid is also seen in Ladakh, where it is one of the main indigenous forms. However, Ladakh variants often have feet and legs and wield a bow. There are no such appendages or accoutrements in the Spitian example. Although the outline is differently shaped, the quadpartite arrangement of the four circular motifs of the Spiti mascoid also occur in Upper Tibet (where they appear as spirals). The two rectangular mascoids with pinched sides in Spiti recall a common style in Upper Tibet.

Next Month: Ancient Artistic Horizons Further Expanded!