October 2015

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung as we once again explore the ancient rock art of Spiti! This issue contains the second of a three-part article. The first part of this article is featured in last month’s newsletter. Before we view the art, let us revisit the elusive term Bon / bon.

A better definition of Bon in 508 words

Regular readers will remember that in the January 2015 newsletter there was a definition of the word bon / Bon. Here I shall improve upon that definition. In this regard, I want to thank Dan Martin for his suggestions. Bon / bon has proven a loaded term, one engendering quite a bit of scholarly controversy in the last half century. While mine is certainly not the final say on the matter, I hope this contribution will help highlight the complex semantics of the word.

The Bon religion arose circa 1000 CE with the rediscovery and recreation of texts supposedly hidden during a wave of persecution in the late 8th century CE. This religion, which shares much of its ethics, doctrines, philosophy and mysticism in common with Tibetan Buddhism, has come to be referred to by its adherents as Yungdrung Bon (practitioners are known as Bonpo). The term yungdrung (g.yung drung) literally means ‘swastika’, conveying the eternal or indestructible nature of the religion. In Yungdrung Bon conceptions, bon more or less carries the same set of connotations as the Sanskrit word dharma does in Tibetan Buddhism. There is a more strongly Buddhist influenced form of the religion that evolved in the 17th and 18th centuries CE named New Bon (Bon gsar-ma).

The teachings of Yungdrung Bon are divided into nine branches or vehicles (theg-pa), a system of classification also present in the Nyingma (rNying-ma) sect of Tibetan Buddhism. Indeed, the latter five vehicles of Yungdrung Bon, known as the ‘Bon of Fruition’ (’Bras-bu’i bon), contain versions of sutras, tantras and profound methods of mind training (rDzogs-chen) comparable to the Nyingma sect. The first four vehicles of Yungdrung Bon, the ‘Bon of Causes’ (Rgyu’i bon), are marked by rites of divination, healing, protection and death among others, which are suffused with non-Buddhist materials of an archaic character. Thus Yungdrung Bon has actively propagated a diverse range of religious traditions as its core theology.

The Bon of Fruition but particularly the Bon of Causes retains traces of customs, rituals, myths and historical lore that predate the 11th century CE. In their earlier forms these non-Buddhist traditions do not appear to have constituted a fully institutionalized or systematized religion. This amorphous body of traditions organized along regional, tribal and political lines is commonly called bon by Tibetans and this sense of the word has been widely adopted in Tibetan studies. Bon as a generic designation for ancient religion in Tibet includes three major historical phases: 1) prehistoric (pre-7th century CE; predating the main introduction of Buddhism in Tibet), 2) imperial period (circa 630–850 CE; marked by still not well understood interactions with Buddhism), and 3) post-imperial (circa 850–1000 CE; period of cross-fertilization with Buddhism). In this bon there are two major sources of religious traditions: autochthonous (originating within the Tibetan cultural world) and assimilated (foreign inputs adapted to the Tibetan cultural milieu). The usage of bon to denote ancient non-Buddhist religion in Tibet probably arose retroactively. In Tibetan texts dating to the imperial and post-imperial periods, bon is more narrowly defined as the corpus of rituals and myths and the priests who promoted it.

Sundry folk religious practices in the contemporary Tibetan world are also popularly labeled bon. Moreover, the term bon is sometimes applied to refer to localized religious traditions further afield in places such as the Hindu Kush, Pamirs, Siberia, Mongolia and China. These cult traditions may or may not be related to the ancient bon of Tibet. Finally, as a verb, bon-[pa] means ‘to recite spells’ or to ‘express mystic knowledge’.

A Survey of the Rock Art of Spiti – Part 2

Please see last month’s newsletter for the introduction to this article. For a comprehensive review of rock art in Spiti see the July 2015 Flight of the Khyung. In this second part of the article the following sites are treated:

- Lari Tangmoche (La-ri thang-mo che; 3250–3260 m)

- Jowa Desa (Jo-ba sdad-sa; 3430–3450 m)

- Lari West (3270 m)

- Tabo (Ta-po; 3280–3305 m)

- Angla (dBang-la?)

- Poh Thangka (sPo-thang-ka; el. 3405–3440 m)

- Gang Chumik (sGang-chu-mig; 3670–3690 m)

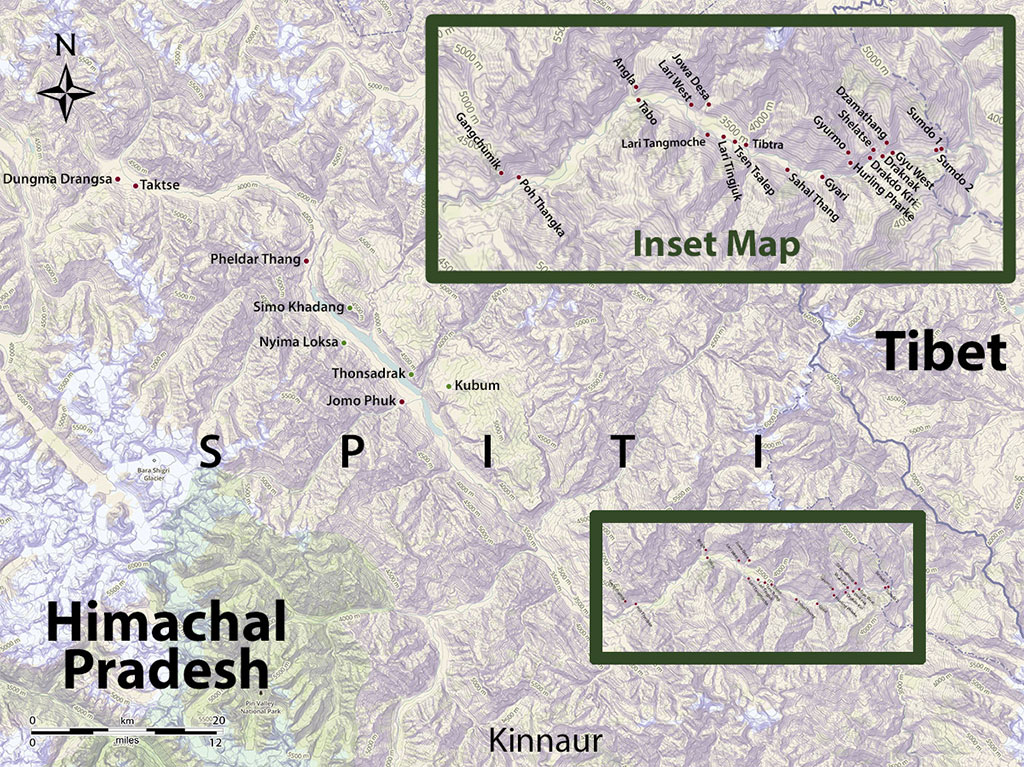

The rock art sites of Spiti: red dot denotes petroglyphs, green dot denotes pictographs. Map by Brian Sebastian and John Vincent Bellezza. Click to enlarge.

Lhari Thangmoche

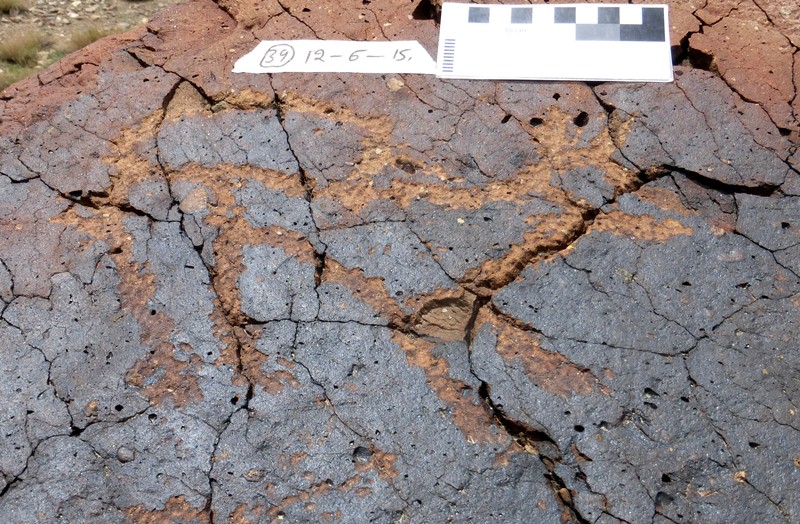

Fig. 15.1. Three wild ungulates (the top specimen has been partially obliterated) forming an integrated composition. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 15.2. Portrait of solitary quadruped (24 cm long). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 15.3. This appears to be a male argali sheep (12 cm long). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 15.4. A male ibex in an unique style (11 cm long). Early Historic period or later.

It is not common to depict the male sexual organ in the zoomorphic rock art of Spiti.

Fig. 15.5. Three hunters armed with bows (right side, center and left side of middle tier of boulder) and various wild caprids and possibly other animals. All figures Protohistoric period except archer on the left, who appears to be an Early Historic period addition to the hunting scene.

Fig. 15.6. What appears to be a typical Spitian hunting composition consisting of two wild caprids and an archer. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 15.7. A geometric form. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 15.8. Segmented sub-rectangular form with linear extensions to the right (12 cm high). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 15.9. Counterclockwise swastika (middle), emblematic anthropomorph to the right (round head, long narrow body, stick appendages and arms pointed downward) and what appear to be symbols and possibly animals. Early Historic period.

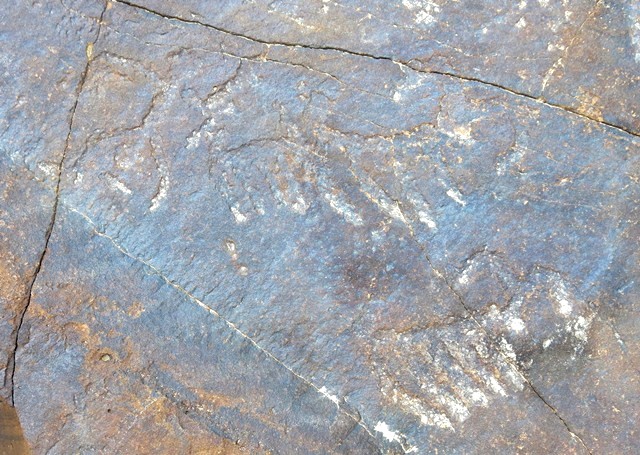

Fig. 15.10. Curvilinear subjects. Protohistoric period.

Jowa Desa

Fig. 16.1. Two wild ungulates. Protohistoric period.

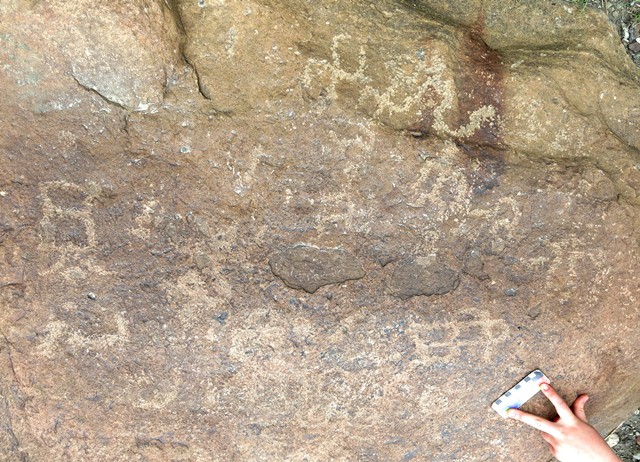

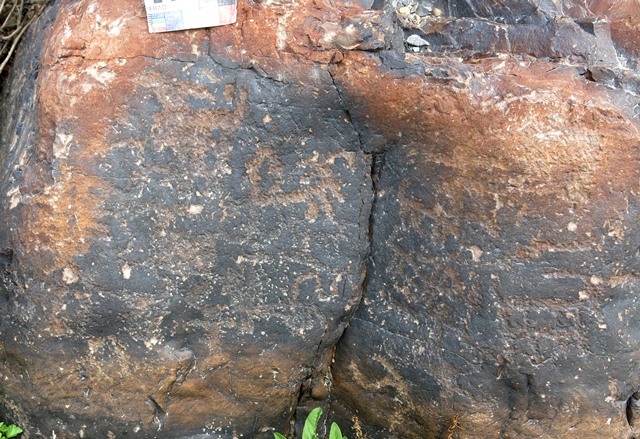

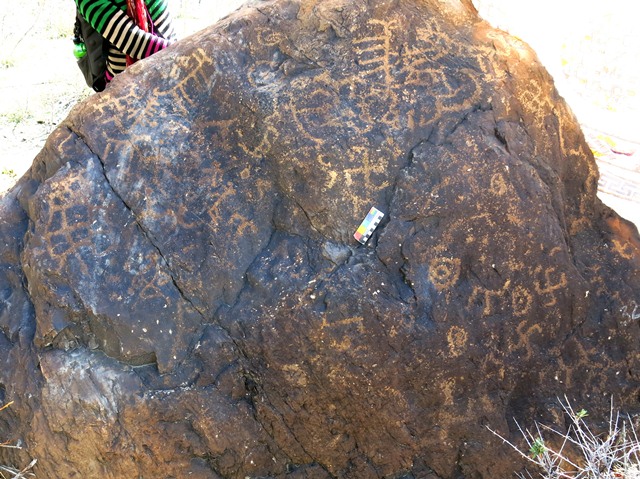

Fig. 16.2. Boulder with large mass of wild caprids and perhaps other figures. These petroglyphs are highly eroded. Protohistoric period.

Boulders such as this one seem to chronicle the natural history of wild caprids in all its exuberance. The dozens of carvings allude to the fecundity and cultural centrality (at least for some sections of society) of the ibex and blue sheep in ancient Spiti.

Fig. 16.3. Portrait of an ibex on the same boulder as fig. 16.2.

Fig. 16.4. Boulder top covered in wild caprids in standard styles of depiction. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 16.5. Male (top left) and female figures (bottom right). Note how the female has what appear to be two children with her. She may also be depicted giving birth. Protohistoric period.

It is not clear whether these anthropomorphs represent human figures or ones with a mythic or divine identity. Be that as it may, this composition seems to depict a family, a rare type of portrayal in the rock art of Spiti.

Fig. 16.6. Close-up of female and juveniles in fig. 16.5. The womb and possibly the birthing process are represented by a circle. Arms straight out, several fingers on each hand are also depicted.

Birthing figures are known in Upper Tibetan rock art but they are rare (for an example, see Bellezza 2001: 359 [10.81, 360 [10.82]]). Such types of figures are more common in the rock art of north Inner Asia and other regions. The womb / female genitalia are often represented by circles in this kind of rock art. That the Spitian figure appears to have two children enhances the fertility theme this composition seems to carry.

Lari West

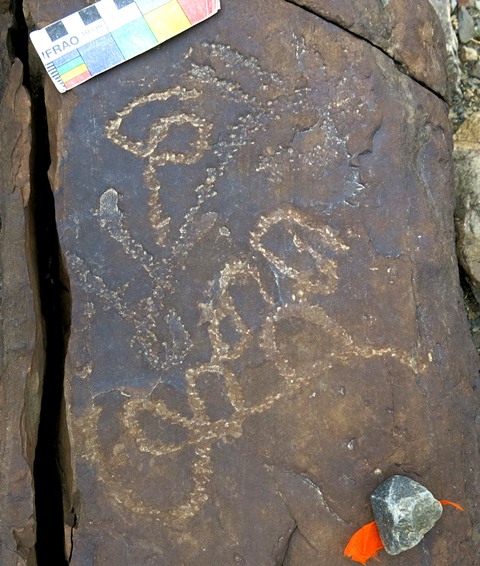

Fig. 17.1. A long-tailed carnivore. The long tail curling over the body seems to indicate that this is the depiction of a feline (tiger or snow leopard). Protohistoric period. Photo courtesy of Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

In style, this feline carving is not unlike a pair found at Dzamathang (see September Flight of the Khyung, fig. 8).

Fig. 17.2. Four or five wild caprids and two anthropomorphs (right side). Protohistoric period. Photo courtesy of Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

There are no graphic signs that this is a hunting scene.

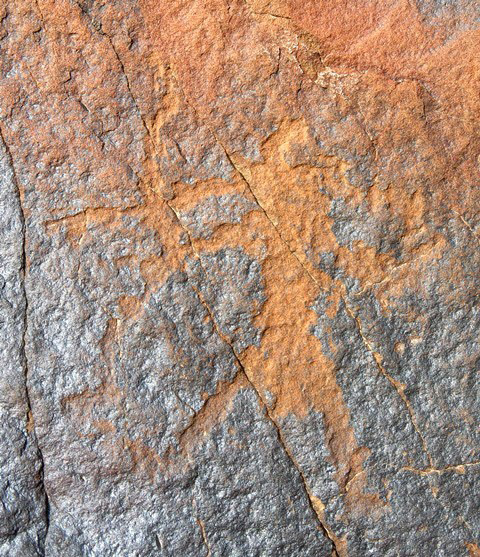

Fig. 17.3. Unusual depiction of what appears to be an archer. This figure has three ray-like or horn-like extensions on the head and a triangular torso. Protohistoric period. Photo courtesy of Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

The addition of vertical lines extending from the top of the head is rare in the rock art of Spiti but fairly common in that of Upper Tibet.

Fig. 17.4. Two archers (bottom right) among wild caprids. Protohistoric period. Photo courtesy of Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

This is a typically styled complex hunting scene. The male gender of the archer on the right is depicted in no uncertain terms.

Fig. 17.5. Wild caprids along upper portion of image dating to the Early Historic period. Complex geometric design covers much of the rest of this face of the boulder. It is attributable to the Protohistoric period. Photo courtesy of Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

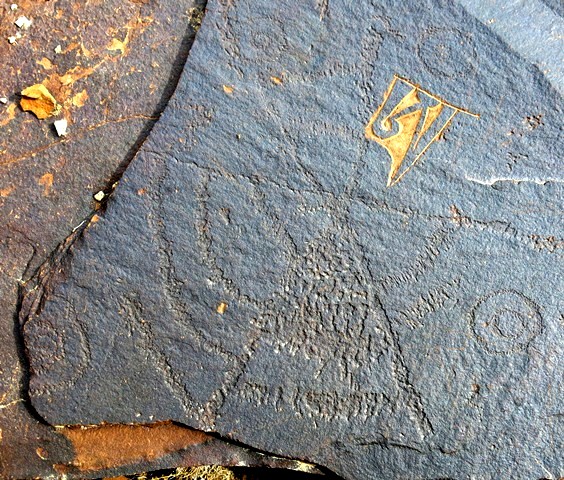

Fig. 17.6. Wild caprids and the Tibetan letter O or syllable Om (upper middle), the syllable Om repeated twice (lower left). Early Historic period or Vestigial period.

The wild caprids are typical of the historical phases of rock art in Spiti. These styles of art often lack the gracefulness and vitality of earlier rock art in the region. These petroglyphs and inscriptions appear to mark a major cultural transformation in Spiti from the paramountcy of cults of the blue sheep and ibex to the rise of literacy and scripturally ordained religious traditions.

Tabo

Fig. 18.1. Part of a long row of Buddhist chorten (mchod-rten) at Tabo. There are around 220 now highly eroded rounded structures (bum-pa) of earth in this construction. They rest upon a massively built stone base. Probably late 10th or 11th century CE.

This kind of religious monument is also found at a number of Buddhist monastic sites dating to the second diffusion of Buddhism (bsTan-pa phyi-dar) in western Tibet. For instance, there is an example at Bedongpo Gonpa Lhoma (Bral gdong-po dgon-pa lho-ma) in Guge (Bellezza 2014: 258, 259).*

A photograph taken by E. Ghersi in 1933 of this long row of chorten in Tabo is found in Klimburg-Salter 1990: (153 [fig. 6]). A photo published by Thakur (2001: 32 [pl. 1] shows only minimal development around this monument. Now the area has been encroached upon by apple orchards and other constructions. Francke (1914: 38) noted that one of many long rows of chorten in Tabo contained at least 216 specimens and that these lines of chorten were the forerunners of mani walls. However, as plaques with carved prayers dating to the Early Historic period are known in Upper Tibet (see April 2011 Flight of the Khyung), their development seems to have taken an independent course from chorten well before the construction of the long row of them at Tabo. Thakur (2001: 30) claims that the long row of chorten at Tabo belonged to the Bonpo because there are so many of them and petroglyphs are found in surrounding areas. It is true that petroglyphs are found in the vicinity but these belong largely to an earlier era and have no direct relationship with the row of chorten. Thakur (2008: 32) discusses an elephant carving on now destroyed boulder, comparing it with elephant carving at Chilas (after Jettmar 1987).

Fig. 18.2. Wild caprid (20 cm long). Protohistoric period.

There are other wild caprids and sundry subjects on this same boulder.

Fig. 18.3. Two wild caprid (possibly argali) in a typical Spitian style. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.4. A deer in a geometric style of art with large, elaborate antlers. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

This deer is comparable in style with one at Lari Tingjuk (see fig. 14.15 in last month’s newsletter).

Fig. 18.5. Two animals (bottom) and a partially destroyed geometric subject consisting of a triangle inside a square. Note the carved outer square.

Fig. 18.6. Six or more wild caprids, which appear to form an integrated composition. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.7. Carving of an ibex (17 cm long). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.8. Wild caprids and possibly other figures. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 18.9. Wild caprids across the face of a boulder. These petroglyphs are now highly eroded. Protohistoric and Early Historic periods.

Fig. 18.10. A group of interconnected caprids and curvilinear subjects, most of which appear to form an integrated composition. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.11. A deer carved on the same boulder as fig. 18.10.

Fig. 18.12. A lion with one paw raised (10 cm long). Early Historic or Vestigial period.

Lions in the same aspect and time frame are found among Tibetan talismans known as thokcha (thog-lcags). There are wild ungulates on the same south side of this boulder.

Fig. 18.13. Boulder with archer (top left), two raptors (below archer) and a variety of wild caprids. On this boulder face there are approximately 70 figures in total, almost all of which date to the Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.14. A close-up of the two birds with outstretched wings in fig. 18.13.

Birds in fully indigenous styles are rare in the rock art of Spiti. There are of course horned eagles (khyung) discussed in the August Flight of the Khyung but these constitute a Greater Western Tibet genre of rock art. In the July Flight of the Khyung, I theorize that the paucity of avian rock art may be due to a strong chthonic component in the mytho-ritual traditions of prehistoric Spiti.

Fig. 18.15. An emblematic anthropomorph, arms pointing downward and what may be a wild ungulate carving to the right. These two petroglyphs possibly form a single composition. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

This boulder and others like it situated in an orchard on the north side of Tabo have been subject to much disruption.

Fig. 18.16. A pair of anthropomorphs (each around 7 cm in height), one with arms pointing up and one with arms pointing down. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

These figures appear to be male but it is possible that they represent both genders.

Fig. 18.17. Ostensible anthropomorph (middle) and linear subjects (animals?). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.18. Two anthropomorphs and other figures possibly depicting animals. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 18.19. Male anthropomorph, with arms spread of the Protohistoric period (bottom) and clockwise swastika of the Early Historic period (top).

Fig. 18.20. Three anthropomorphic figures with two suns and crescent moon in close proximity (upper portion of image). The middle anthropomorph appears to be depicted in movement, a common form of portrayal in later rock art. There is a wild caprid petroglyph above these figures. In the bottom portion of the boulder are geometric designs. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.21. Anthropomorph and feline (upper left), tree (upper right) and other figures. Probably Vestigial period or later. Note the recently carved letters: P T.

Fig. 18.22. Anthropomorph arms raised (lower left), lizard-like anthropomorph with arms spread out and hands depicted (upper right) and other figures. Early Historic period.

The anthropomorphic art of the Early Historic period assumes a number of expressive poses and a variety of styles but the iconic quality is diminished as compared to the earlier rock art.

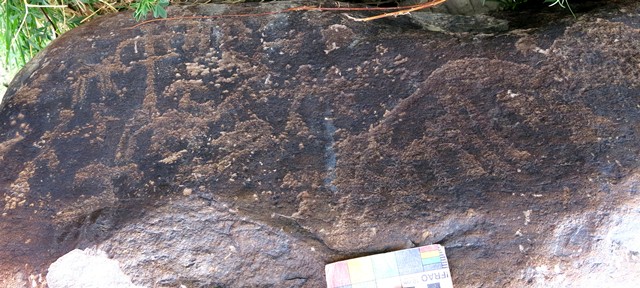

Fig. 18.23. A west side of a large boulder completely covered in carvings. These include swastikas, circles, wild caprids and anthropomorphs. Note the tiger on the top right side of the rock (see August Flight of the Khyung, fig. 11). These carvings are typical of the Early Historic period.

Rock art of the Early Historic period is well represented at Tabo. There are also a few Tibetan inscriptions that date to this time (see below and next month’s Flight of the Khyung). The large amount of rock art from the Early Historic period suggests that Tabo was an important cultural center before the founding of the Buddhist monastery there in 996 CE. The valley is wide at Tabo and the climate is relatively mild, perhaps explaining it attractiveness to earlier settlers.

Fig. 18.24. Four swastikas oriented in both directions and anthropomorph (bottom). Probably Early Historic period.

Fig. 18.25. Two male anthropomorphs (middle) surrounded by wild caprids. The human figures and some of the animals seem to form a single composition. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.26. Three anthropomorphs (left half), animals and other figures in a possible hunting composition. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.27. Wild caprids and possible anthropomorphic figures. Early Historic period.

Fig. 18.28. Three vertically arrayed anthropomorphs (bottom half) and wild caprids. Early Historic period. The middle human figure appears to be somewhat more recent than the other two.

Fig. 18.29. Top portion of large boulder with wild caprids and a number of anthropomorphs. Early Historic period. Note the recent carvings.

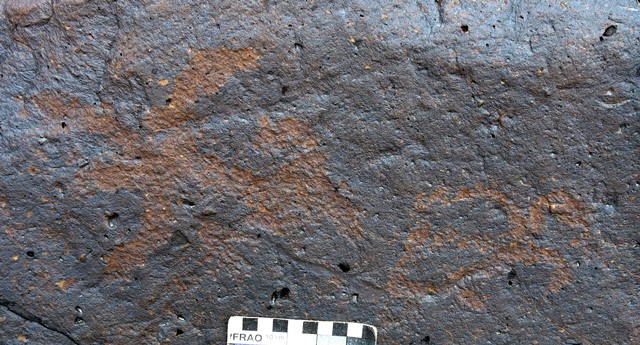

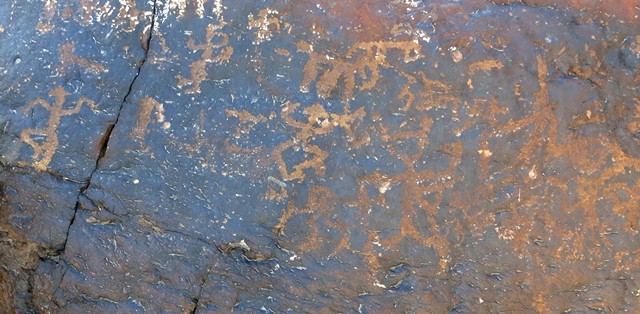

Fig. 18.30. Three figures of the right side of the boulder in fig. 18.29. They appear to be dancing or engaged in some other ceremonial or celebratory activity. At the top of the image is a Tibetan inscription also of the Early Historic period. It reads: rta-zog (horse requisitions). There is a Tibetan inscription at the bottom of the image as well but it is less legible. The first three characters possibly read: gsang (secret).

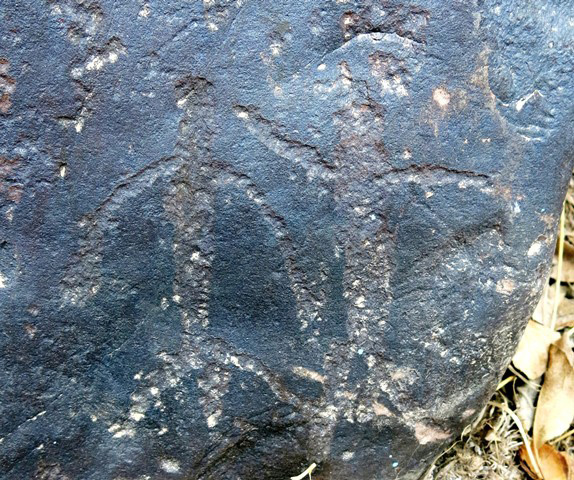

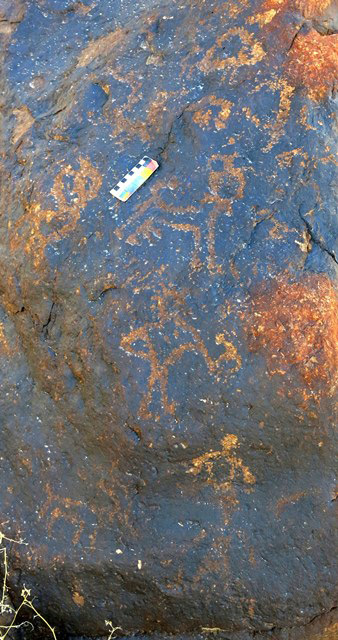

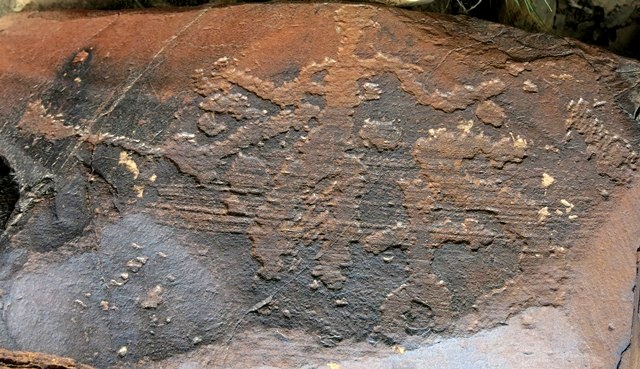

Fig. 18.31. Five or six anthropomorphic figures and swastika (middle of top) on the left side of the boulder in fig. 18.29. These anthropomorphs are depicted engaged in an energetic activity. Note that two of the human figures don pyramidal headgear. The Early Historic period Tibet inscription reads rta-zog-pa (horse requisitions).

It appears that this phrase has to do with the requisitioning of horses for military purposes. The most likely historical context for the inscriptions in figs. 18.30 and 18.31 is the Tibetan war machine of the Imperial period. This scenario is supported by an inscription(s) in the Old Tibetan language recorded by Thakur (2001: 232–235), which according to the image helpfully provided in his work reads: rta zag / rta zog pa / rta zog pa / mag gi rta zog / gral ta po / ki rnam. In his reading, Thakur misreads zog as cog and translates the inscription as follows: ? / Owner of the horses / Owner of the horses / The horses of mag / The part of the Ta-po range… Thakur (ibid.) holds that there are no military or administrative terms in this inscription. To the contrary, this inscription(s) is indeed all about administrative functions in a military setting. My reading of this inscription or group of inscriptions is: “Horse conveyances / Horse requisitions (if zag = zog). The horse requisitions. The horse requisitions. The horse requisitions of the army (mag; Classical Tibetan = dmag). The organized [horses] of Ta-po.” It would appear that horses for the Tibetan cavalry or a homegrown Spitian regiment were collected or pastured in Tabo.

Fig. 18.32. Wild caprids and anthropomorphic figures. Note the bird-like cruciform at the bottom of the boulder (middle). Early historic period.

Fig. 18.33. A close-up of anthropomorphs on the lower left side of boulder in fig. 18.32. Here we see that the two large anthropomorphs (one on right only partially visible in image) appear to have been retouched. The original carvings of emblematic anthropomorphs date to the Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.34. Anthropomorph (lower middle; 10 cm high) and sundry figures. Early Historic period.

Fig. 18.35. Curvilinear designs that possibly include highly stylized anthropomorphs. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.36. Anthropomorph possibly with bow and wild caprid. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.37. Large carving of a chorten. Vestigial period.

This petroglyph was clearly inspired by the introduction of Buddhism in Tabo. Carvings such as this one constitute the historical terminus of the Spitian rock art tradition.

Fig. 18.38. Geometric form of unknown abstract or figurative value. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.39. Three swastikas (right side) and circle (left side). Early Historic period.

Fig. 18.40. Markings on a boulder. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 18.41. Curvilinear design. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 18.42. Geometric designs and wild caprids. Probably Early Historic period.

These petroglyphs are found on same boulder as fig. 18.24.

Fig. 18.43. Quadrangular shapes. Protohistoric period or Early Historic period.

Fig. 18.44. Carving of a hand (middle top) counterclockwise swastika (left side) and other figures. Protohistoric period.

For another possible hand carving, see last month’s newsletter, fig. 9.7.

Fig. 18.45. Circular subjects of unknown function. Early Historic period.

Fig. 18.46. Counterclockwise swastika (16 cm high). Protohistoric period.

There is another swastika on the top of the boulder but it is not as easily seen.

Angla

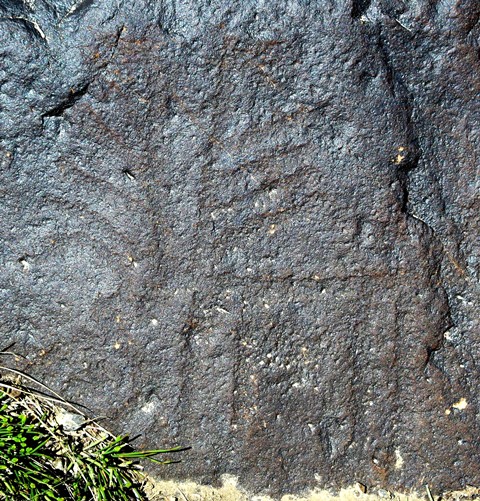

Fig. 19.1. Possible anthropomorph (left side) and animals. Protohistoric period. Photo courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

Fig. 19.2. Various geometric forms and animals. Probably Early Historic period. Photo courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

Fig. 19.3. Rectilinear subject wrapped around two sides of rock. Early Historic period. Photo courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

Fig. 19.4. A variety of unusual geometric forms that almost have the appearance of letters. Probably Protohistoric period. Photo courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

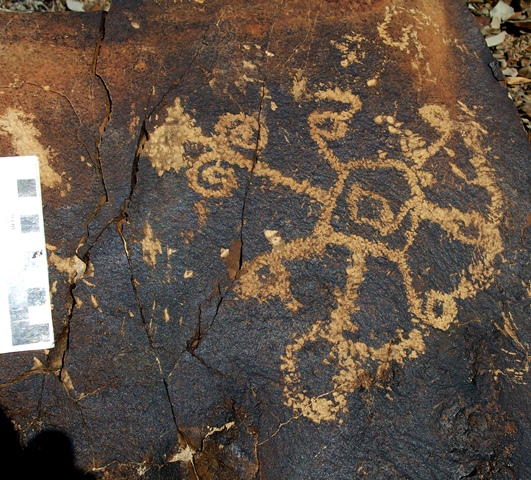

Fig. 19.5. An unusual curvilinear subject comprised of lines terminating in circles and spirals that radiate from a central pentagonal form. Early Historic Period. Photo courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

Poh Thangka

Fig. 20.1. A conventional portrait of a solitary ibex. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.2. A standard portrait of what is probably a blue sheep. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.3. A long-legged wild caprid (8 cm long) and other animals, which may include a carnivore. Protohistoric period. This boulder has been broken as the pace of destruction picks up at this rock art site.

Fig. 20.4. Three animals (upper two figures are wild caprids) forming an integrated composition on a small boulder. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.5. Two anthropomorphs (the larger of the two is 16 cm high) with spheres. Note the long line extending to the left from the larger anthropomorph. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

With arms outstretched this is an unusual depiction. This integrated composition seems to present some kind of mythic theme or religious phenomena.

Fig. 20.6. Horse rider (9 cm long), counterclockwise swastika and possible sun made at different times. The horse rider may date to Protohistoric period; other subjects belong to a later phase of rock art.

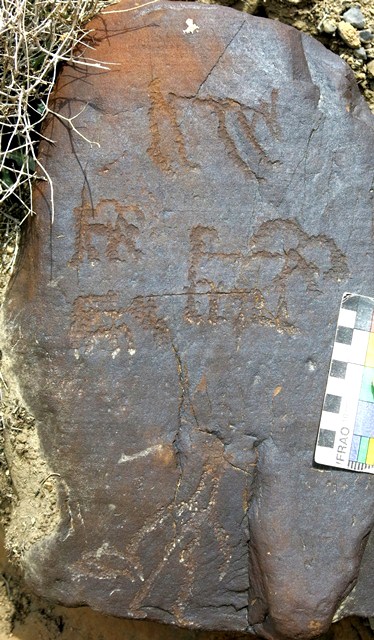

Fig. 20.7. An upper row of five emblematic male anthropomorphs (each around 10 cm high), another anthropomorph with arms brought around to the waist (lower right) and subdivided square (lower left). The anthropomorph on the far right and the one in the middle of the upper row and the lower specimen as well as the geometrics date to the Protohistoric period. The two less re-patinated anthropomorphs on the left side of the upper row date can be attributed to the Early Historic period. The anthropomorph second from the right may even date to a later phase of rock art.

These carvings are an excellent example of how emblematic representations persisted over time in the anthropomorphic rock art of Spiti. Styles changed becoming less geometric in form and with a greater range of arm and legs positions. However, anthropomorphic rock art of the Early Historic period does not possess the elementary boldness or iconical quality of the prehistoric epoch. The form of the lower anthropomorph may possibly be that of a female (see fig. 20.8). There are carvings on other sides of this boulder as well.

Fig. 20.8. Close-up of lower anthropomorphic figure in fig. 20.7.

Fig. 20.9. Centaurial figure (left; 20 cm long) and rectangle with inner curvilinear and rectilinear motifs (right; 23 cm long). Protohistoric period. This boulder was recently split in two as part of a local campaign to eradicate all boulders in the area.

The combining of what appears to be the qualities of humans and caprids in the figure on the left may be purely coincidental. If not, it speaks reams about the close relationship between the early inhabitants of Spiti and the wild animals with which they interacted on a regular basis.

Fig. 20.10. Wild caprids and anthropomorph (lower right). Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.11. Standing archer attacking one or more wild caprids in this standard hunting scene. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.12. Four animals (the largest of which is a wild caprid) and what appears to be an archer in pursuit (left side). This might be an integrated composition. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.13. Two anthropomorphs (right and left sides) and two or three wild caprids and other figures between them. This appears to be an integrated composition despite the variable weathering of the figures. There are no indications that this is a hunting scene. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.14. There are three blue sheep and a possible carnivore on the top half of this boulder. On the lower half there is an anthropomorph with torso rendered as two parallel lines (11 cm high), which seems to be carrying a bow. The anthropomorph seems to be older than the animal figures. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.15. What appears to be a male archer in pursuit of wild caprids. The multiple legs shown in this single composition depict at least three different animals. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.16. Bowman with exaggeratedly large arrow. Below him is a wild caprid. To the right of these two figures is what appears to be a very large arrow pointing downward. These three figures constitute a single composition. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

The arrow is a prominent instrument in the archaic rituals and ancestral traditions of Tibet. In this composition a function related to the success of the hunt and the fecundity of wild animals is perhaps portrayed.

Fig. 20.17. Standing archer (11 cm high). This boulder has been broken and the quarry of the hunter is no longer extant. There is also recent graffiti on the boulder. Early Historic period.

Fig. 20.18. Horse with saddle (18 cm long) and two rectilinear geometrics. The horse and geometric connected to it below probably date to the Early Historic period. The geometric on the left is a more recent creation.

Fig. 20.19. At the top of the boulder are two animals, the larger of which may be a horse with rider. On the upper middle part of the rock are five figures including animals and what may be a standing archer. On the lower middle part of the rock are several curvilinear geometrics including two circles connected by a line and a circle with four smaller circles around its edge (left side). On the lower part of the stone is an intricate rectilinear subject (right side). Most of the figures on this boulder date to the Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.20. Close-up of central circle surrounded by four subsidiary circle (7 cm across) shown in fig. 20.9.

Fig. 20.21. Three complex rectilinear geometric designs and anthropomorph (top right). The combined height of the two geometrics on the left is 34 cm. Protohistoric period.

These carving occur on the same boulder as fig. 20.7.

Fig. 20.22. Complex geometric design carved on small boulder. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.23. Two complex curvilinear subjects and minor figures. Protohistoric or Early Historic period. Note the recently carved letter N.

Fig. 20.24. Centipedal design (Protohistoric period) and complex rectilinear consisting of a ladder-like design repeated thrice (Early Historic period).

Fig. 20.25. The geometric subject on the left (14 cm long) probably dates to the Protohistoric period. This portion of the boulder has been stripped of much of its veneer. The geometric on the right belongs to a later period. This boulder was broken in half by those keen to expand apple orchards.

Fig. 20.26. Square subdivided into various parts with possible zoomorphic characteristics (16 cm high) carved on small boulder. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.27. Complex linear designs possibly with anthropomorphs and animals among them (total length 32 cm). Possibly both Iron Age and Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.28. The horizontal top of a boulder covered in maze-like carvings that are highly eroded. There may possibly be anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures interspersed between the geometric designs. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.29. Complex curvilinear geometric (11 cm high). Note the dots in the center of various curved cells. Iron Age.

Fig. 20.30. This petroglyph has the appearance of a ritual object or ceremonial structure (16 cm high). It is comprised of a square base, narrow middle section with four lines extending outward, and rounded upper section with a finial of four lines. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 20.31. A counterclockwise swastika (7 cm tall). Iron Age or Protohistoric period. This carving is found on a fragment of a boulder that was deliberately broken recently.

For a view of the entire broken boulder, see July 2015 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 18. Swastikas are the most common symbol in the rock art of Spiti, occurring in all phases of production. Whatever the specific field of meaning, the swastika must have been an auspicious symbol in ancient Greater Western Tibet, as it is today.

Gang Chumik

Fig. 21.1. Typical portrait of an ibex (14 cm long). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 21.2. Larger oval and others carvings. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 21.4. A rectangle divided into four upper and four lower units of varying size (25 cm long). The pair of large units on the left has an X marked across it. There are also other internal elements in this complex geometric subject. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 21.5. Two geometric forms (each 7 cm long), the one on the left vaguely looks like the endless knot (pa-tra) of Bon and Buddhism, while the specimen on the right resembles a turtle (a sacred animal in Tibetan conceptions). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 21.6. A composition consisting of a number of geometric forms. These include a central triangle (with internal elements; 18 cm long) from which eight long curved lines extend outwards (four from the left side, two from the peak and two from the right side). Beyond these lines there are are circles on all four sides of the composition, each with an inner circle. The circle on the lower left side was partially obliterated when the surface of the rock was removed at some time in the past. Iron Age or Protohistoric period. The letter A was carved over the composition at a much later date.

The identity of this intriguing composition is beyond our reckoning. It could represent a ritual structure, magical diagram or astronomical chart, among other possibilities.

Bibliography

Bellezza, John V. 2014. 2014. Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: A Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites on the Tibetan Upland, Residential Monuments, vol. 1. Miscellaneous Series – 28. Sarnath: Central University of Tibetan Studies. Online version: Tibetan & Himalayan Library (THlib.org): http://www.thlib.org/bellezza, 2011.

____2001. Antiquities of Northern Tibet: Archaeological Discoveries on the High Plateau, Delhi: Adroit.

Francke, August H. 1914. Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Part 1, Personal Narrative. Reprint, Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, New Imperial Series, vol. 38., S. Chand, 1994.

Klimburg-Salter, Deborah. 1990. “Tucci Himalayan Archives Report, 1. The 1989 Expedition to the Western Himalayas, and a Retrospective View of the 1933 Tucci Expedition”, in East And West, vol. 40. (nos. 1–4), pp. 145–171. Rome: IsMEO.

Thakur, Laxman, S. 2008. “Bonpos of the Western Himalayas”, in South Asian Studies, vol. 24 (no. 1), pp. 27–36.

____2001. Buddhism in the Western Himalaya: A Study of Tabo Monastery. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Next Month: More great rock carvings and paintings from Spiti!