October 2014

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung, a newsletter dedicated to the culture, art and archaeology of ancient Tibet! This special issue features the Eurasian ‘animal style’ rock art of Upper Tibet, adeptly executed carvings distinguished by their gracefulness and exuberance. This month’s and next month’s article offer the most comprehensive coverage of this distinctive genre of Upper Tibetan rock art to date.

Sinuous Shapes: The Eurasian animal style rock art of Upper Tibet – Part 1

Introduction

With the coming of the Iron Age in the first millennium BCE, a new form of art appeared in Inner Asia. Distinguished by animals carved, cast and worked in a variety of poses and activities, the so-called animal style spread from Mongolia and China in the east to Iran and Anatolia in the west. During the Iron Age, Tibet was also a recipient and propagator of the animal style. Rock art in this tradition of figuration is found in both northeastern and northwestern Tibet, ancient gateways to the wider Eurasian world. Adoption of the animal style was one milestone in a series of productive contacts between early Tibetan tribes and other peoples of Inner Asia and beyond.

Different materials were used to produce animal style objects including gold, silver, bronze, stone, wood, bone, and felt. In most Inner Asian regions, deer, ibex, equids, felines and birds-of-prey are the most dominant species represented in the animal style. In Tibet this artistic tradition was manifested in petroglyphs (there are no pictographs in this style) and in copper alloy artifacts. In the animal style rock art of Upper Tibet, yaks, deer and antelope predominate, reflecting environmental and cultural conditions prevalent on the high plateau.

Animals in the animal style are variously depicted on the tip of the hooves, bodies coiled, recumbent with folded legs, head turned back, and with curvilinear body ornamentation. In the rock art of Upper Tibet, we find three of these defining features: animals on the tip of their hooves, heads regardant and curvilinear body decoration.

With Bronze Age precursors in many different regions and cultures, the Eurasian animal style appears to have arisen in the early first millennium BCE. However, it is not clear where this type of art first originated or how it spread as widely as it did. Multiple centers of development, as part of an Iron Age zeitgeist (with technological, socioeconomic, ideological and political facets), are indicated. Actually, the animal style is not one genre or kind of art but rather a group of interrelated styles produced by different peoples, which found full expression in the second half of the first millennium BCE.

Animal style artifacts and rock art have been discovered in Mongolia, Xinjiang, Gansu, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Ningxia and other parts of China, southern Siberia, northern Pakistan, northwestern India, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Kirgizstan Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Iran, as well as in Upper Tibet. Certain stylistic traits of Inner Asian animal art are found further afield in Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Romania, Moldavia, Turkey, the Caucuses, and even in Celtic Europe. The pervasive dissemination of the animal style in Eurasia is probably predicated on long-distance transfers of peoples, ideas and goods, as well as on a globalized social consciousness that suffused the continent.

The rock art and especially the portable objects in the animal style of north Inner Asia tend to be characterized by fluid, tortuous or fanciful depictions; those of Upper Tibet less so, mirroring the more austere conditions of an extremely high altitude world. Animal style art in Upper Tibet is founded on two schemata or templates underpinning its execution: a rectilinear type associated with indigenous art and a sinuous type that may have been borrowed from other regions of Inner Asia, where it is widespread.

In the animal style of Upper Tibet, body ornamentation is curvilinear and includes three major kinds of motifs or elements: single volutes (curled or spiraling lines on the forequarters and hindquarters), scroll or double volute (formed from interconnected volutes placed centrally on the body) and the S-shaped design (occupies the middle of the body). Although single volutes are a common form of ornamentation in other regions in which the animal style spread, it is uncommon in the rock art of Upper Tibet. Conversely, the S-shaped motif is much less common in north Inner Asia than it is in Upper Tibet.

There are no less than 450 animals in over 160 rock art compositions exhibiting the scroll or ‘S’ motifs in Upper Tibet, all concentrated in just one district: Ruthok. Although the inspiration behind the creation of the volutes, scroll and ‘S’ may have come from north Inner Asia, they were executed in a wide variety of ways in Ruthok, reflecting indigenous artistic development over centuries. The scroll and ‘S’ pictorially enhance the vitality and dynamism of zoomorphic compositions. The symbolism or meaning behind these motifs remains a mystery. I have speculated that they may possibly represent the life-force of animals. It seems likely that new religious ideas, mythologies or customs were behind their espousal or approbation in the rock art of Upper Tibet.

Cultural interactions encompassing Tibet and north Inner Asia were already underway by the Late Bronze Age, as indicated by parallels in the development of funerary monuments and rock art. For a discussion of ancient exchanges between Upper Tibet and north Inner Asia, see my books Antiquities of Upper Tibet, Zhang Zhung and The Dawn of Tibet (for bibliographic details, see “Books” section of website), as well as other issues of Flight of the Khyung.

Also see with Bruneau, L. 2013: “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’” in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28, pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS: http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf

This paper comprises the entire volume and examines various aspects of the animal style with a focus on transcultural links between the rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh and that of north Inner Asian regions. It contains an extensive bibliography of works pertaining to animal style art in Inner Asia.

Another source for animal style rock art is L. Bruneau and M. Vernier, 2010: “Animal style of the steppes in Ladakh: A presentation of newly discovered petroglyphs”, Pictures in Transformation: Rock Art Research Between Central Asia and the Subcontinent (ed. L. M. Olivieri). South Asian Archaeology 2007, Special Sessions 2. Oxford: BAR International.

Animal style rock art on the western Tibetan plateau and its broader geographic and cultural ramifications were first studied by the celebrated French archaeologist Henri-Paul Francfort. Among several of his works noting the distribution of animal style art in Ladakh and Upper Tibet is the following: H.-P. Francfort, D. Klodzinski, G. Mascle, 1992: “Archaic petroglyphs of Ladakh and Zanskar” in Rock Art in the Old World. Papers presented in Symposium A of the AURA Congress, Darwin Australia. 1988 (ed. M. Lorblanchet), pp. 147–192. Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts.

With only one exception, all animal style rock art in Upper Tibet is situated in the northwestern district of Ruthok (Ru-thog). The single outlier is located to the south in the Guge region of western Tibet (this petroglyph is featured in next month’s Flight of the Khyung, fig. 55). The concentration of animal style rock art in Ruthok indicates that this area actively interfaced with other regions of Inner Asia. Ruthok shares a frontier with Ladakh and Xinjiang, which were also recipients and propagators of animal style rock art and portable objects. As I have explained in other writings, Ruthok was a kind of clearinghouse or vanguard for the introduction of Iron Age cultural elements into Upper Tibet. The flourishing of the animal style in Ruthok may possibly allude to the reception in Upper Tibet of the riding horse, iron implements and weapons and other aspects of Iron Age technology.

The importance of Ruthok in the dissemination of cultural traits and materials introduced from other parts of Inner Asia is underlined by the existence there of mascoid (anthropomorphs in emblematic form) rock art, a subject matter often attributed to the Bronze Age. In Upper Tibet mascoid rock art occurs only in Ruthok, while it is widely distributed in north Inner Asia.

The Upper Tibetan animal style forms a distinctive branch of this Eurasian decorative tradition. Indigenous styles of rock art originating in the Late Bronze Age (circa 1200–900 BCE) and Early Iron Age (circa 900–600 BCE) were subsequently modified to incorporate animal style esthetic imperatives, as a reflection of broader ideological and technological currents circulating in Inner Asia. With a rock art tradition already firmly in place, Upper Tibetans adopted the animal style on their own cultural terms, not simply as something to be imitated. The same can be said of earlier mascoid rock art: Upper Tibetan variants, while being influenced by the art of Ladakh and north Inner Asia, are disparate in form. In the case of Upper Tibetan mascoid and animal style rock art, a process of assimilation followed by a period of endogenous development is indicated.

As I have made clear in various publications, the precise dating of rock art is not yet feasible, forcing a reliance on indirect methods of analysis. On stylistic and technical grounds, animal style rock art in Upper Tibet can be shown to have made the transition from the Iron Age to the Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE). This rock art appears to be well represented in protohistoric rock panels in Ruthok. There are however no indications that animal style rock art was produced in the Early Historic period (650–1000 CE). It is never directly associated with inscriptions or Early Historic period styles of carving. Thus, while permutations of the Upper Tibetan animal style seem to have outlived the creation of this art in the steppes, it did not endure as late as the Tibetan imperium (however, in silver vessels, horse harness pieces and copper alloy talismans of this period, both evolving and vestigial decorative elements of the animal style are discernable).

Animal style art in Upper Tibet can be expansively dated to 600 BCE to 600 CE. The actual time it fell out of favor with petroglyph carvers, nevertheless, may be some centuries prior to the terminus ante quem suggested here. The historical persistence of animal style art in Upper Tibet is attributable to the survival of archaic customs and traditions in this very remote region. Interestingly, what might be called pseudo animal style art is still being fabricated by Tibetan blacksmiths today.

We do not yet know what types of contacts led to the introduction of the animal style in Upper Tibet. We can hypothesize that vectors of foreign influence may have included traders, emissaries, missionaries, colonists, or soldiers who penetrated as far south as Ruthok. Of course, Upper Tibetans may have also travelled north and west to interact with other peoples, carrying back the materials and ideas that led to the formation of their animal style.

A mix of factors over time may well be involved in the adoption of the animal style in Upper Tibet, including more strident forms of contact. Violence and coercion through war and raids may possibly be implicated by virtue of the animal style being concentrated in a single frontier district. Had more benign forms of transmission been solely responsible for the establishment of this art in Upper Tibet, it should have eventually percolated to conterminous parts of this vast region. The monumental and rock art records demonstrate that Ruthok was very closely aligned culturally to other parts of Upper Tibet. Therefore, the nonabsorption of animal style rock art in other districts seems anomalous. If sociopolitical forces contributing to the formation of the animal style were indeed imposed upon Ruthok, areas further removed from the frontier may have been under no such compulsion to receive it. Foreign imposition of the animal style is possibly also hinted at by its minority status: with the exception of Rimodong (Ris-mo gdong; Rock Face Art), never did it become the dominant form of depiction at any of the more important rock art theaters in Ruthok. In Guge only a single animal style petroglyph is known, as if it was injected there by an extraneous agent. Be that as it may, most major rock art styles in Upper Tibet enjoy wider geographical dispersion.

So, who was this carrier of the animal style to northwestern Tibet? Geographically and chronologically speaking, one of the best candidates is the Saka-Scythians, a cultural complex of varying linguistic and ethnic affiliations. Some of these interrelated tribes spread to northern Pakistan in the second century BCE.* On their sweep southward (where they became known as the Indo-Scythians) they must have passed close to or even over the borders of Ladakh and northwestern Tibet. These nomadic or semi-nomadic tribes were in possession of the so-called Scythian triad consisting of horse harnesses, weapons (including the broadsword) and animal style art. An earlier Iron Age incursion into Ruthok could have been launched by Scythian related peoples living in Xinjiang.

On the legend of the Saka conquest of Chilas, see “Babusar: Passage of the Pious” in the blog of Salman Rashid, May 3, 2013: http://odysseuslahori.blogspot.com/2013/05/Babusarpass.htmlThe rock art of Ruthok constitutes strong circumstantial evidence that the influence of the Saka-Scythians reached that corner of the Tibetan plateau. Nevertheless, we still have no direct archaeological evidence (such as Saka style burials and archaeologically secure artifacts) to prove that these tribes actually came to Ruthok. My archaeological surveys indicate that Ruthok in the Iron Age and Protohistoric period was a highly developed agrarian region, with an extensive network of fortified settlements of the Upper Tibetan type. If the folklore of the region is a true indicator of the historical situation, perhaps an elite social component, rather than a large occupying force, brought the animal style with them. Local folklore speaks of an individual named Shenpa Merutse (Bshan-pa sme-ru-rtse), who came from the north to rule over Ruthok in ancient times. When this individual might have lived (if he did), however, has not been determined.

As noted, the most common species in the animal style rock art of Upper Tibet are the wild yak, antelope and deer. Wild caprids, equids and felines are also represented in this genre of art. The rock art record strongly suggests that the wild yak was the favorite quarry of ancient hunters in Upper Tibet. Hunting scenes with this animal easily outnumber all other rock art hunting compositions. Although most of its functions have been superseded by the domestic variant, the wild yak was once essential as a source of food, skins for building shelters, hair for cordage, wool for clothes, dung for fuel, horns and guts for vessels, among many other products. As we can see from the ethnographic and textual records, wild yaks occupied a key cultural position in Upper Tibet, reflecting its important economic functions.* Personal and household protective spirits and clan gods assume the form of the wild yak, as do deities of the lakes and mountains. The wild yak also figures in an origins tale of the bovid psychopomp in the Old Tibetan language text Pt 1068. The cult of the wild yak is still deeply ingrained in Tibet (please consult my books and articles for more detailed information). In fact, there is no other animal more emblematic of Tibet than the yak.

For a long-term perspective on the economic functions of yaks in Tibet, see D. Rhode et al. 2007: “Yaks, yak dung, and prehistoric human habitation of the Tibetan Plateau”, in Developments in Quaternary Sciences, vol. 9, pp. 205–224.The formative role of the wild yak in Tibet is filled in north Inner Asia and in some other parts of the Eurasian continent by the ibex, a prized quarry of hunters, sacred symbol and cult figure in ancient times. That Tibet is essentially a yak country while much of the rest of Inner Asia is ibex territory helps to culturally and economically differentiate these two expansive regions from one another. This fundamental difference is embodied in animal style art in Upper Tibet, which varies in theme from its northern counterparts, despite it drawing from a common Iron Age Weltanschauung.

The Tibetan antelope, which is endemic to the Tibetan plateau, is another animal that takes the place of the ibex in Upper Tibetan rock art. Antelopes are found as far west as upper Ladakh, while the range of the ibex reaches almost as far east as this region. The rock art record mirrors this contemporary ecological reality, with the Ladakh corpus dominated by the ibex, while this species of wild caprid is absent from the Upper Tibetan corpus. The implication of this state of affairs seems to be that the current geographic distribution of the ibex and antelope on the western Tibetan plateau has remained more or less stable for at least 2500 years. This is not surprising, as the biogeographical conditions of the lower reaches of Ladakh and Upper Tibet are very different.

The deer is the animal that thematically best connects the rock art traditions of Upper Tibet to those of the steppes, deserts and mountains to the north. In addition to having been a source of food, the deer has had sacred connotations wherever it is found. In Tibet, the deer is a good-fortune bestowing figure, psychopomp, and object of sacrifice for a whole host of ritual operations (I have written quite extensively on the ancient religious functions of deer).

It is necessary to mention the buffering or bridging role played by Ladakh in the transmission of north Inner Asian rock art traditions to Upper Tibet. As Bruneau and I have commented in our paper, “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh”, Ladakh rock art in general shares stronger affinities with the rock art and artifacts of north Inner Asia than does Upper Tibet. Mascoids and animal style petroglyphs in Ladakh are quite often intermediate in form to those of Upper Tibet and north Inner Asian regions. This suggests that certain cultural influences coming from the north were modulated or reconfigured in Ladakh before moving on to Ruthok. Yet, rock art bearing the hallmarks of the animal style is more common in Ruthok than it is in Ladakh. Local tradition, esthetic preferences and sociopolitical conditions, among other factors, may account for the popularity of the animal style in Ruthok.

To introduce the reader to the breadth of Iron Age artistic traditions germane to our discussion of Upper Tibetan rock art, several animal style petroglyphs from north Inner Asia are presented below. These wild ungulate carvings share a schema and forms of ornamentation directly comparable to rock art in Upper Tibet. Each region of Inner Asia created its own animal style vocabulary, echoing the existence of diverse cultures and conditions.

This carving is attributed to the Saka-Scythians and was probably made between the 7th and 2nd centuries BCE. The body of the ibex is decorated with three volutes. The flexed legs and graceful curves of the body and neck of this petroglyph are shared by some animal style rock art in Upper Tibet.

For this petroglyph, see: http://www.kyrgyzstantravel.info/glossary/cholpon-ata_p.htm

For the same image as above and for other ibexes in the animal style from Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan, see the webpage “Museum of Petroglyphs”:

Also see the same images by Leonid Plotkin: http://www.flickr.com/photos/85173665@N00/8200417702

http://www.flickr.com/photos/_leonid/8200419026/in/photostream/

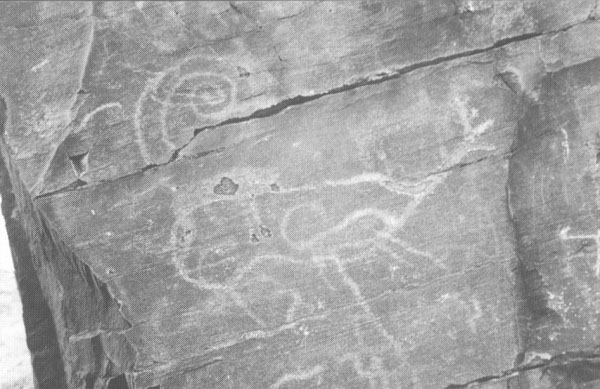

Fig. 2. A carving of what appears to be a deer, Aprauzen, southern Kazakhstan. There is also an isolated volute carved on the same rock surface. Image from “Petroglyphs in Southern Kazakstan”, by Kenneth Lymer.

For this petroglyph, see: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/prehistoric/past/past29.html

The above petroglyph can also be attributed to the Saka-Scythians of the Iron Age. The forequarters of the animal bears an S-shaped motif while the hindquarters is ornamented with a volute. The S embellishing this figure is strongly reminiscent of animal style rock art in Upper Tibet.

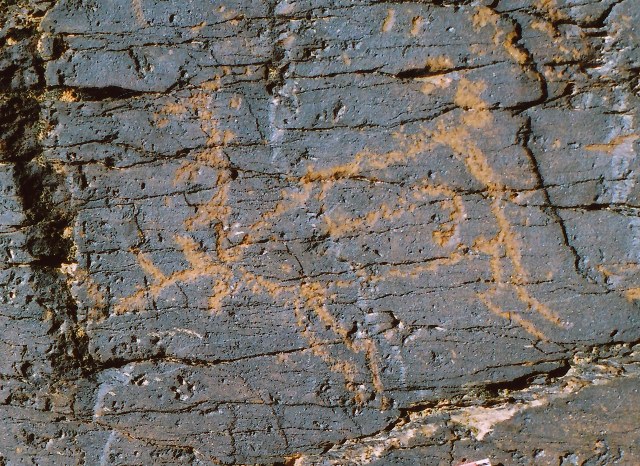

This image comes from a large and important archaeological database of rock art and monuments in Mongolia, by E. Jacobson-Tepfer and J. E. Meacham, 2009: Archaeology and Landscape in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia. See figure 1108 (RA_PETR_TG_0870).

http://img.uoregon.edu/mongolian/index.php

As the above authors observe, the deer in fig. 3 was rendered in a style mimicking the Scythian art of Arzhan and Pazyryk in the Altai. The pointed hooves and horizontally aligned antler of this composition also characterize some animal style rock art in Upper Tibet.

Fig. 4: Deer carved on one side of a wooden vessel, Satma Mazar, Xinjiang, Iron Age. Photograph courtesy of Christoph Baumer.

The shape of this deer and the scroll ornamenting its body are strongly reminiscent of the Upper Tibetan animal style. In Upper Tibet, however, the scroll is usually centered inside the body rather than forming part of the outline of the figure, as in this example from Satma Mazar. Note how the deer stands on the tip of its hooves, an animal style trait found throughout Inner Asia. The head of this deer may be partially obliterated. The wavy single antler overarching the back of the animal is a north Inner Asian stylistic figure. Here we have an animal style figure whose form is intermediate between Upper Tibet and the Altai / Southern Siberia, just as Xinjiang is geographically intermediate between Upper Tibet and the northern steppes.

Fig. 5. Deer carved on the other side of the wooden vessel shown in fig. 4, Satma Mazar, Xinjiang, Iron Age. Photograph courtesy of Christoph Baumer.

This deer with its exaggeratedly large overarching single antler, projecting snout, elongated body, and front and rear volutes, spells out robust stylistic affinities to Scytho-Siberian cervid art. The carvings on this wooden vessel from Satma Mazar embrace both north Inner Asian (Mongolia, Kyrgyzstan, etc.) and south Inner Asian (Upper Tibet, Ladakh) animal style characteristics. This is a superb example of how animal style figures were transformed as they diffused from one region to another, incorporating stylistic and thematic features of adjoining regions to create a unique artistic and cultural lexicon.

Volutes of varying degrees of complexity ornamenting the bodies of wild ungulates also occur on Scytho-Siberian and Xiongnu felt saddle pads with appliqué designs. These, too, are comparable to some Upper Tibetan animal style petroglyphs.

Picture Gallery, Comments and Analysis

Note: This month’s article is devoted to deer in the animal style (next month we will explore other animals in this genre). There is other cervid rock art in Upper Tibet in a variety of strongly indigenous styles, but these are not included in this study. In contemporary Upper Tibet, two species of deer are reportedly found in peripheral locations, but they are now both critically endangered. These are the white-lipped deer (Cervus albirostris) and the Tibetan red deer (Cervus elaphus wallici).

All photos shown below were taken in Ruthok by the author. The rock art illustrated dates to the Iron Age (600–100 BCE) and Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 600 CE). It is difficult to be more precise because Iron Age cultural traits appear to have been retained as anachronisms until as late as the Early Historic period (650–1000 CE).

Based on Tibetan textual and ethnographic records, the function and significance of cervid rock art is potentially very broad indeed. What specific artists had in mind for specific compositions however is beyond our ken. Assuming an inclusive perspective, deer and other wild ungulate depictions in Upper Tibetan rock art may possibly encapsulate one or more of the following assignations:

1) Record of hunting expeditions

2) Charm for the attraction of game

3) Token of thanksgiving or an offering made to conclude a successful hunt or other activity

3) Good luck symbol or good fortune attracting instrument more generally

4) Part of an array of objects for any manner of apotropaic, curative or destructive rituals

5) Totem or symbol of clan or tribal affiliation

6) Mark of social status or identifying symbol for a hunter, priest, warrior, chieftain or other individual

7) Zoomorphic deity of a personal, protective or territorial nature

8) Psychopomp for the dead

9) Commemorative marker for deceased or mythic persons

10) Figures in a narrative, legend or myth

Volutes, scrolls and S-shaped designs were sometimes carved in isolation at rock art sites of Ruthok. These seminal motifs constitute the central focus of ornamentation in the animal style of Upper Tibet. Such curvilinear forms mimic the sinuous schema upon which much animal style rock art is based.

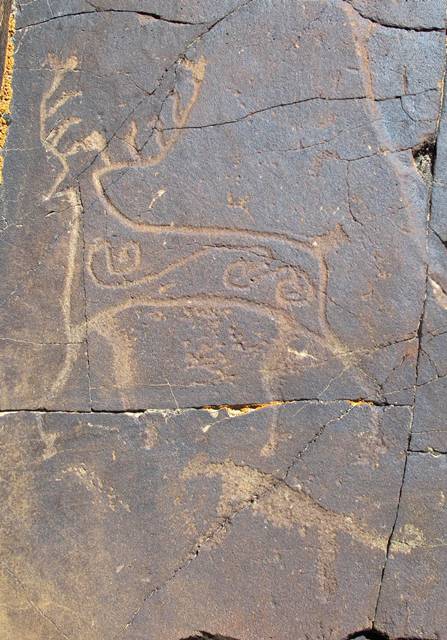

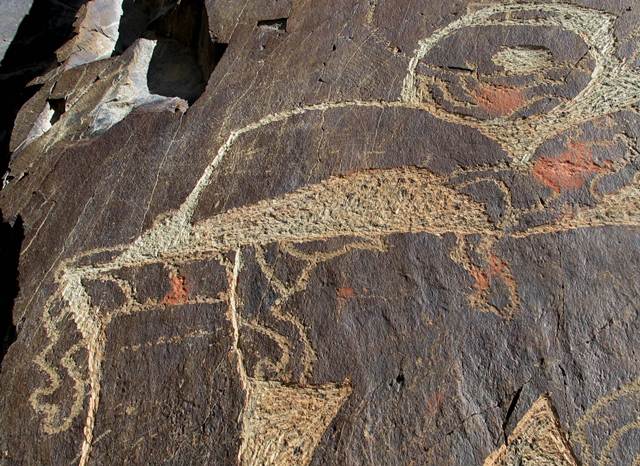

Fig. 7. Two wild ungulates exhibiting the S-shaped motif in the middle of their bodies. This is an integral composition.

The branched horns of the upper figure identify it as a deer, while the lower figure is more ambiguously rendered (the shape of its body suggests a deer or antelope). The tail of the upper animal sticks straight out from the body. The rectangular body of the two figures is basic to much indigenous rock art of Upper Tibet. The four legs of each of the animals are bent, a common feature in the region’s zoomorphic depictions, spanning the prehistoric epoch (pre-7th century CE). The flexed legs impart a sense of movement to the figures. The uniform wear and carving technique employed show that these two wild ungulates were made by the same artist(s). Perhaps the male and female of the species were intended.

Fig. 8. A well-executed stag with four-pronged V-shaped antlers, small upright tail and two legs. This deer was carved on its own. An S was engraved in the middle of the body, a defining feature of the animal style in Upper Tibet. Its short tail sticks straight up.

Fig. 9. A more stiffly rendered stag at the same rock art site as fig. 8. This figure is part of a large hunting scene. The V-shaped antlers each have three tines and all four legs are shown. The S motif was added to this animal, which was carved in an indigenous style.

Fig. 10. The S motif nicely balances the curvilinear lines of the body of this deer, lines that are also repeated in the legs and neck.

The V-shaped rack of the stag and the depiction of four legs are indigenous stylistic traits. An examination of the carving technique and the patination of the engraving demonstrates that the anthropomorph is an integral part of the composition. The upper torso of this figure is diamond-shaped, while the lower torso is triangular. The bodies of many anthropomorphs in Ruthok assume a geometric form. It holds what appears to be a rectangular shield in one hand and a long linear object in the other. A bird seems to be perched on the shoulder of the anthropomorph. Perhaps this is an early example of falconry on the high plateau. There are several other examples of what appear to be hunting birds in the rock art of Upper Tibet. The relationship between the deer and anthropomorph is difficult to discern. Instead of a prosaic hunting scene, a ritualistic or mythic theme may be intended.

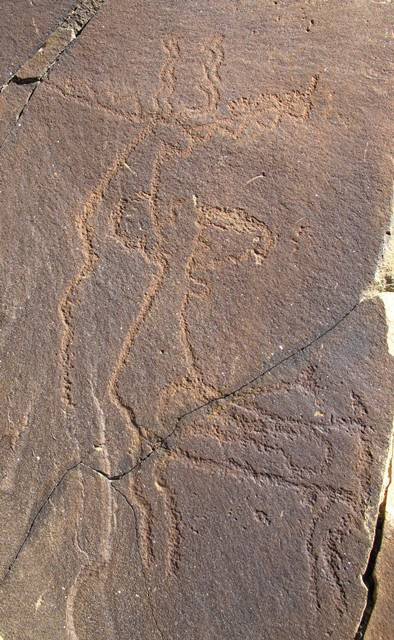

Fig. 11. A solitary stag with the S motif. The tines of the antlers have the appearance of multiple horns. The head appears to be swung back, one hallmark of the Eurasian animal style. The lower hindquarters of the deer were rendered as a triangle and the four legs as single lines.

Fig. 12. A more crudely carved solitary deer with a prominent set of antlers but no clearly designated head. Two S-shaped motifs were added to the body of the animal, a smaller anterior one (merges with the head) and a larger posterior example. Legs are depicted but no tail.

Although there are other animals on the same rock panel, this petroglyph appears to form an individual composition. A scroll was placed in the middle of the rectangular body of the deer. The neck is also rectangular while the head is pointed. The four legs are widely set apart, conveying a gamboling motion. This composition may possibly date to the first half of the first millennium BCE.

Fig. 14. The deer and antelope in this composition exhibit central scrolls and were executed using the curvy lines of the animal style. The deer is shown with four legs and the antelope with two.

To maintain their smooth circularity, the bodies of these two animals are unpunctuated by a tail. The standing archer is facing in the direction of an antelope, identified by its long, spiraling horns. The relationship between the two animals and hunter is not clear. They may possibly belong to different compositions placed next to each other by successive artists. The position of the exaggeratedly large deer is curious. It may possibly have been conceived as a spirit ally or mascot of the hunter, a venatic tradition known in more recent times in Upper Tibet, Ladakh and the northern areas of Pakistan.

Fig. 15. A gracefully executed deer with a well developed scroll. This petroglyph stands on its own.

In this variation of the animal style, the forequarters and hindquarters of the deer are rendered as circles, a more intensive articulation of the sinuous schema. This petroglyph is more lightly etched into the rock than others thus far examined. The engraving technique used and style of the petroglyph may indicate a protohistoric rather than an Iron Age antiquity. It is not clear whether the artist conceived this animal in a perspective requiring two or four legs.

Fig. 16. This deer is similar in form to the one in fig. 15, but it is more deeply carved and patinated. An Iron Age date seems indicated for this petroglyph. Another deer in the same style was carved next to it (not shown).

This petroglyph has undergone much wear, somewhat obscuring its original form. The adeptly cut antlers of this figure are very different in design to others thus far pictured. Instead of the tines being positioned perpendicular to the horns, as in the above examples, they are depicted as scalloped lines cut into wide, almost circular antlers. The tail of the deer is long and hooked. The joining of the parallel lines of the legs at the bottom, reveals that this animal was created using a perspective in which only the two legs facing the viewer are visible.

The style of this deer carving and the high degree of patination suggests that it should be attributed to the Iron Age. This type of rock art with its rectilinear schema reveals a strong indigenous bias. In the middle of the body of the animal is a scroll with three volutes. The hooves of the four legs are graphically depicted. The carnivore (wolf?) is identified by its general form and long tail. Predation scenes such as this one are fairly common in the rock art of Upper Tibet. They may portray both a fact of natural history and in symbolic form more violent aspects of ancient society such as war, vendettas and legal punishments. Carnivore attack scenes are found in Iron Age rock art and objects from other parts of Inner Asia as well.

Fig. 18. A deer with vertically aligned antlers and an elaborate scroll that merges with the underbelly of the animal. This petroglyph stands on its own.

The incorporation of volutes and scrolls into the outline of animals is commonplace in other regions of Inner Asia, however, in Upper Tibet it is unusual. This deer has all four legs visible.

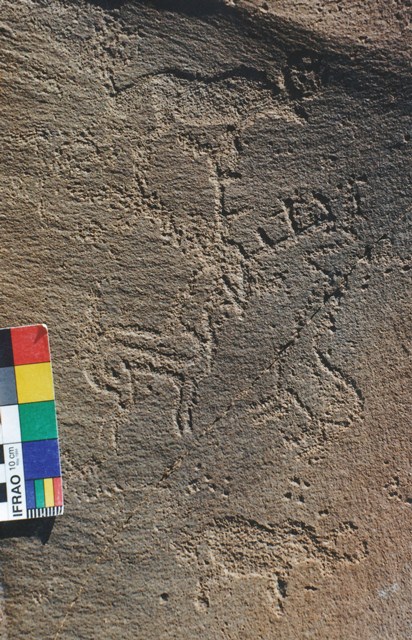

Fig. 19. What appears to be an integral composition consisting of a deer, antelope and two wild yaks.

The deer is ornamented with a scroll and the antelope with an S. They each have four legs. The two wild yaks flanking them were engraved as silhouettes with no body ornamentation. The yaks appear to have only two legs depicted. This composition illustrates that single artists or those working in one spot in the same timeframe were capable of creating more than one style of rock art.

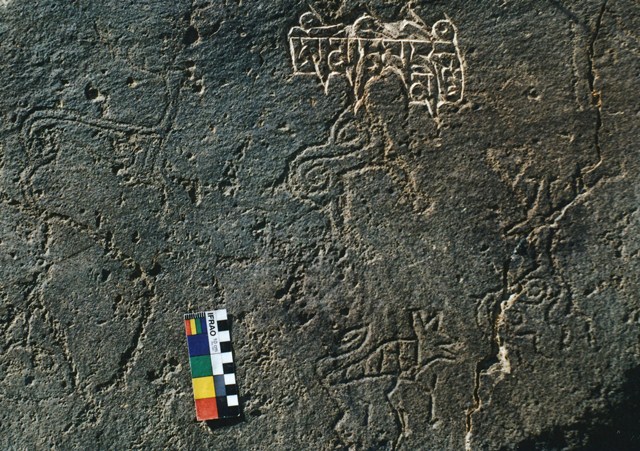

Fig. 20. A deer standing alone (upper left portion of photograph), a wild ungulate partially obscured by a mani mantra of later Buddhists (upper middle), and a stag chased by a striped carnivore (lower right).

These four creatures rendered in the animal style were created in the same timeframe, but probably not as part of a single integral composition. The carnivore with gaping mouth, pointed ears, stripes and long curled tail appears to be a tiger (for more tiger art, see the August 2012 and November 2014 Flight of the Khyung). The deer it is chasing is depicted looking back at its attacker in what must be a gesture of great fear. Both the prey and predator are rendered with four legs each, while the other two animal style figures have two legs each.

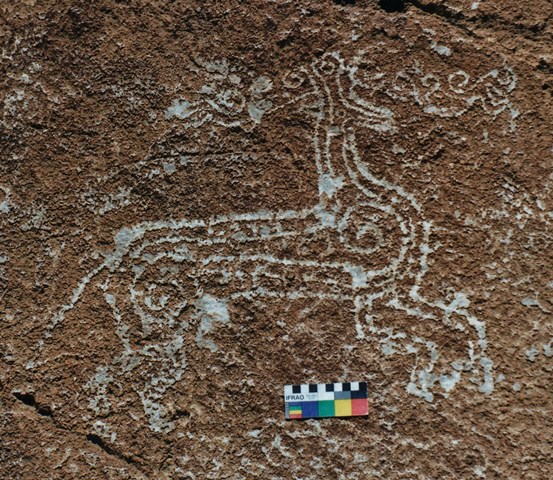

This petroglyph was carved on a limestone surface, an unusual rock art medium in Upper Tibet. The horns of the deer are comprised of a series of volutes resting above the trunk of the horns, which are portrayed as single lines. Surrounding much of the scroll is a set of parallel lines that extend upwards to circumscribe the neck and head of the animal as well. The eye of the deer is depicted, something missing in less elaborate renditions of the animal style. The flexure of the four legs communicate a sense of movement. Found at the Ruthok site of Khampa Racho (Kham-pa rwa-co), this large petroglyph has been published in:

Antiquities of Upper Tibet, p. 252 (Fig. XI-3h); see books section of this website for bibliographic details.

Chen Zhao Fu, 2006: Zhongguo yanhua quanji – Xibu yanhua (The Complete Works of Chinese Rock Art – Western Rock Art), vol. 3, p. 139. Shenyang: Liaoning meishu chubanshe.

Suolang Wangdui (Bsod-nams dbang-’dus), 1994: Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings, p. 76 (Fig. 49), p. 77 (Fig. 50). Chengdu: Sichuan People’s Publishing House.

The antlers of this deer terminate in four triangular protuberances signifying the tines of the animal (one of which has been obliterated by the inscription). This style of antlers appears to have been influenced by north Inner Asian rock art, as have many other compositions at this particular site in Ruthok. Wider animal style influences are also seen in the deer standing on the tip of the one hoof visible (only two legs were depicted in this petroglyph). Fig. 14, supra, is from the same rock art site.

This deer pictured here is located at the same site as figs. 16 and 23. It is adorned with front and rear volutes, a form of ornamentation closely associated with the animal style in other regions of Eurasia. Nevertheless, the overall form of this deer is of Upper Tibetan persuasion. In the perspective assumed by the artist, the set of legs confronting the viewer is fully treated while the set of legs behind them is only partly rendered.

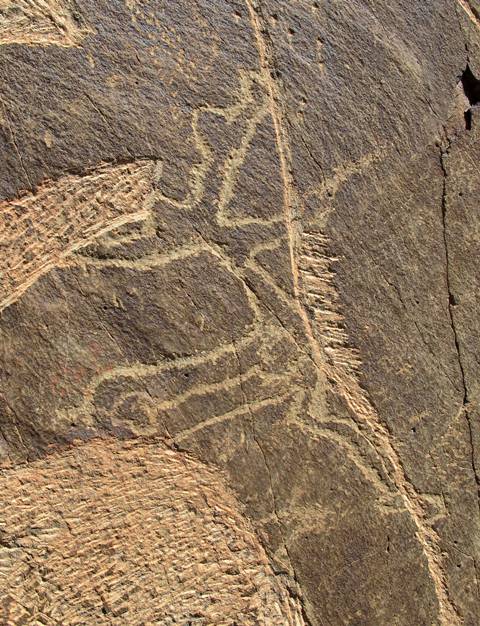

The body of the lower figure in this integral composition contains an ellipsoidal motif nearly forming a figure 8. The head of this animal is not fully formed, rather it merges with the head and neck of a stag looming above it. This stag has adeptly carved antlers that are both vertically and horizontally oriented. These antlers consist of a series of wavy lines. The deer has four stick legs.

The body of the stag is partitioned by vertical and horizontal lines, a style of ornamentation that may possibly predate the animal style in Upper Tibet. The rock art site in which this composition is found contains many petroglyphs that may date to the Late Bronze Age. This particular piece of rock art could potentially date to the Early Iron Age. The relationship of the three anthropomorphs to the two animals is unclear. They may possibly be deer herders or be involved in a ritual exercise involving deer, among many other prospective scenarios.

This deer is found at the same site as figs. 16, 22, 23. Unfortunately, this petroglyph is highly worn and has been marred by the desultory bruising of the rock. The deer is being pursued by a tiger rendered in the same rich style (head and one leg is visible in photograph; for full image, see November 2014 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 67). The body of this animal is full of volutes. Note the fetlock on the left front leg (all four legs are depicted). The antlers of this figure are comparable with those in figs. 22 and 23, betraying esthetic influences that entered Ruthok from the north and/or west. The body decorations of this deer are comparable to a cervid petroglyph at Domkhar (Rdo-mkhar), in Ladakh (see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, pp. 46, 123). Approximately half of all animal style rock art in Ladakh is located at this one site. The ornate decorative treatment of the deer in fig. 26 reveals Iron Age artistic influences emanating from both Ladakh and north Inner Asia.

Deer with bodies fully segmented by a series of lines and dating to the Iron Age are known from the Altai. Images of two examples have been kindly brought to my attention by Professor Esther Jacobson and are contained in the Mongolian Altai Inventory Image Collection (University of Oregon): nos. TG_04132_1 and TG_04132_3. The segmentation of the bodies of the Altaian animal style examples, however, is based on much straighter lines than embellishment of the Tibetan specimen in fig. 26.

This panel of animal style petroglyphs has been published numerous times (for references, see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, p. 49 [fn. 166]). Although it is often attributed to the ancient period, the dominant group of carvings belongs to the historic era. One of the tigers in the scene overlies older rock art in the animal style (see fig. 28). Judging from the deep, narrow and uniform incisions in the stone surface, these highly competent carvings were produced with a sharp steel implement. The style however is contrived and imitative. Whoever created this scene was evidently inspired by older animal style rock art at Rimodong.

The famous site of Rimodong is the only sizable Upper Tibetan rock art theatre where the animal style makes up the majority of carvings, comprising more than 60% of their total number. Rimodong is situated 45 km south of the old Ruthok citadel and modern county headquarters, which comprise the geographic heart of Ruthok, a large basin with ample water. The main route north to Ruthok connecting other major areas of western Tibet passes right by Rimodong, an escarpment rising above the banks of the Rogsum river. Likewise, those heading south from Ruthok would be squeezed into the narrow passage beside Rimodong. Another route from the Indus valley of upper Ladakh passes through Chakgang (Lcags-sgang) before turning north to reach Rimodong, a total distance of around 120 km. Given its placement and aspect, Rimodong is liable to have been an important way station since ancient times. Major channels of trade, sociocultural association and invasion in northwestern Tibet are not likely to have avoided this location. Certainly, Rimodong’s crucial geographic position and the availability of suitable rock faces help to account for the creation of rock art here. Carriers of the animal style in particular made it a focus of their labors.

Fig. 28. A close-up of the striped feline in an imitation animal style, which is superimposed on a caprid with volute seen in fig. 27. The differences in the carving techniques used to create these two petroglyphs is quite dramatic.

The wild ungulate being pursued by the feline (probably a tiger) is also partially visible in the photo. The feline, like the deer in fig. 22, has two legs, stands on the tip of its toes and possesses a rectangular body. For more on rock art palimpsests, see the November 2012 Flight of the Khyung

Fig. 30. A deer and antelope (?) in the animal style and other wild ungulates upon which a mani mantra was superimposed, Rimodong.

The deer is embellished with two volutes and was partly carved over the antelope-like figure with a scroll. The more lightly patinated deer (with four legs) is likely to date to the historic era, while the antelopian animal (with two legs) is attributable to the Protohistoric period.

Next month: More beautiful animal style rock art!