November 2014

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome aboard another Flight of the Khyung! This month we continue our explorations of the Tibetan ‘animal style’, a group of artistic traditions vibrantly depicting animals using curves and circles. As explained in last month’s newsletter, the animal style pervaded much of the vast Eurasian continent in the Iron Age.

Sinuous Shapes: The Eurasian animal style rock art of Upper Tibet – Part 2

Introduction

Part 1 of this article began by examining the relationship between animal style art in Upper Tibet and other regions of Eurasia. The focus then of that article was deer in rock art from the northwestern Tibetan district of Ruthok. This second part of the article is dedicated to other species of animals in Upper Tibetan rock art that exhibit hallmark features of the animal style. We begin with the second most popular subject in animal style rock art of the region: the antelope (tsoe; gtsod).

We know from ancient Tibetan documents that, like deer hunting, antelope were a sought after quarry in the large Upper Tibetan territory known as Changkha (Northern Parts; Byang-kha). Tibetan literature and the oral tradition tell us that antelope horns were used ritually to inscribe magical symbols on the earth and as sacred receptacles. It is also related that the elemental deities, ancient priests and sages, as well as shamans of more recent times, rode antelope to travel afar. It is further recorded that the blood of the antelope was employed in rites of purification in the ancient kingdom of Zhang Zhung.

For an outline of the various functions and meanings of wild animals in Upper Tibetan rock art, see last month’s newsletter. Although the subject of that outline was the deer, it is applicable to all the major wild animals of Upper Tibet. For more information on the sacred functions of wild ungulates in Upper Tibet, please see my various publications.

The antelope rock art shown below possesses distinguishing qualities of the Eurasian animal style such as execution on a sinuous schema, curvilinear body ornamentation, animals on the tip of the hooves, extravagantly long horns, and heads regardant. Nevertheless, the techniques of carving, stylistic features and physical condition of the petroglyphs vary widely. This reflects the development of animal style rock art in northwestern Tibet (Ruthok district) over a wide period of time. This art can be assigned to the Iron Age (600–100 BCE) and Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE). While certain examples may possibly date to the Central Asian Early Iron Age (900–600 BCE), no true animal style rock art in Upper Tibet can be shown to have been made in the Early Historic period (650–1000 CE). On the dating of animal style rock art in Upper Tibet, see last month’s article.

Picture gallery, observations and analysis

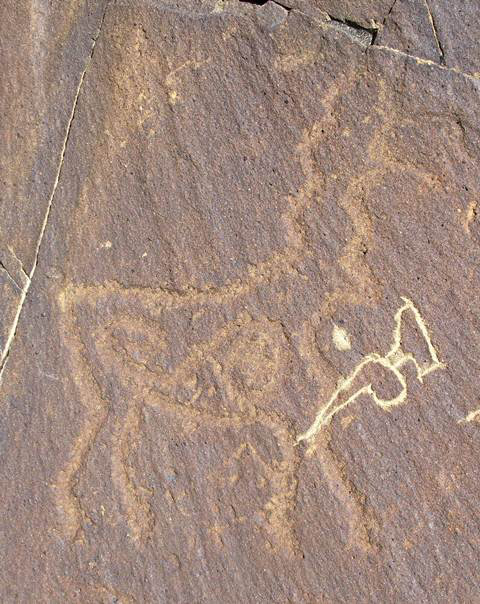

The body of the large antelope is marked with an S-shaped design, a distinguishing trait of the animal style in Upper Tibetan rock art. This motif embellishes a rectangular body, an indigenous geometry in Upper Tibetan rock art. Thus the animal style was naturalized in Ruthok by combining native elements with those of foreign inspiration. Note the fan-shaped upright tail. In this perspective, it appears that only two legs are portrayed. The antelope stands erect, facing in the direction of two or more horsemen armed with bows and arrows. Based on the carving technique, degree of (re-)patination and overall presentation of the figures, only the uppermost horseman appears to be an integral part of the composition (behind it is what seems to be an unfinished horse rider). The exaggeratedly large size of the antelope is common in hunting rock art of Upper Tibet and other regions of Inner Asia. A big size emphasizes the important economic and biological qualities of the animal and is an allusion to the social status and prowess of hunters. Lower down on the same rock panel is a mounted archer and a wild yak forming a different and probably older (Iron Age) hunting scene. In close proximity to these figures, there are two other carvings (horseman (?) and animal) that seem to form separate petroglyphic compositions.

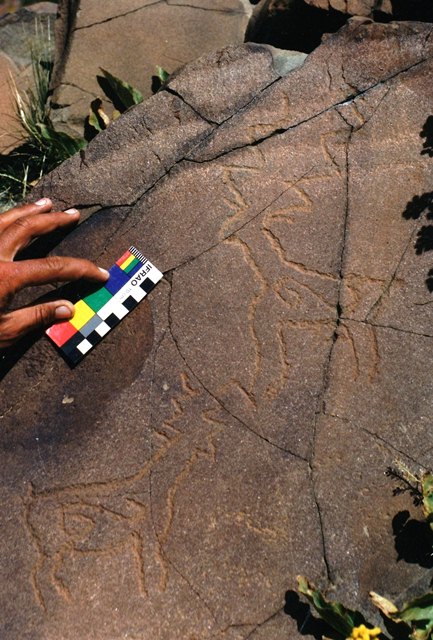

There are around a dozen antelopes and a couple deer on this rock panel all carved in the same mode and exhibiting similar wear and patination qualities, indicating that they were produced in one timeframe but not necessarily by the same artist. They each are shown with two legs. Some of the animals were retouched to varying degrees. The hunter pictured is the only one among all the surrounding animals. This seems to be an indicator of his great courage and ability, an individual who had access to much game. I should note that there is no convincing evidence for female hunters in Upper Tibetan rock art.

Like other antelopes and deer on the panel, this one displays the curvy form of rock art based on a sinuous schema. The outline of the body mimics the lines of the double volute or scroll ornamenting the animal’s body. The long, twirling horns accent the curviness of the body. Only a mature male antelope would have horns even approaching the length shown in this carving.

The standing archer is aiming his bow at the smaller of the two antelopes. The small antelope has a hooked tail and long legs with three bends in them, complimenting the zigzag horns. The ornamentation in the middle of the body has been reduced to a single horizontal line. The position of the long-tailed hound with upright ears conveys the coursing of the animal in the direction of the hunter. Behind him is a much larger antelope that is not being harried by hunters. It has a relatively long tail, double volute body decoration and four legs. Its head and horns are rendered by parallel winding lines. All three figures exhibit similar wear and patination characteristics, and are closely akin to one another in treatment and carving technique. Whether they were made by the same artist or not, the question arises about the function of the large antelope. Perhaps it served a non-game role as a spirit mascot or protector of the hunter (see fig. 35).

In this composition each of the four legs of the antelope are comprised of two parallel lines that bend to form sharp angles. The wavy horns are as long than the animal itself. Inside the body is a scroll. No tail is portrayed. The human figure is armed with a bow and arrow as well as with a long implement that may possibly represent a spear. It has a hourglass-shaped body, which is common in anthropomorphic depictions in Ruthok. The anthropomorph is facing in the opposite direction from the antelope, thus it does not appear to be pursuing the animal. As I have commented in my book Zhang Zhung, p. 174 (see books section of this website for bibliographic details), this composition seems to embody a ritual or mythic theme, rather than a hunting one. As in fig. 34, the antelope here may possibly have been conceived of as a supernatural zoomorphic entity that empowered hunters.

Fig. 36. An antelope upon which the Tibetan letter n was engraved. This antelope has the double volute body decoration of the animal style, but it was largely created using a more indigenous mode of expression. The antelope is depicted with four legs.

Fig. 37. Two antelopes carved in a style very similar to that in fig. 36. The lower specimen has shorter horns. Perhaps the male and female of the species is intended here.

Fig. 38. An antelope whose body ornamentation consists of two small circles connected by a single line.

The triangular head of the antelope is of the same form and size as the swirls of the horns (these horns have been partially obliterated). The rear legs of the antelope are completely straight. On the same rock panel (not pictured) is a wild sheep, another animal, and an unidentified subject created using the same pecking technique seen in the lower half of the antelope. These figures were made in varying styles, and while dating to the same period, they seem to form discrete compositions.

In this composition an antelope appears to be chasing a deer (identified through its branched horns), whose head is swung back to look upon its pursuer. As they exhibit the same carving technique and wear and patination qualities, the antelope and deer appear to form an integral composition. However, the two figures differ somewhat in tenor, with the deer more akin to north Inner Asian animal style art. Each animals has a double volute in the middle of the body and just two legs are shown (this is indicated by the manner in which the parallel lines of each leg are joined at the bottom). In documents written in the Old Tibetan language, the antelope and deer are often paired with one another as the prey of hunters (sha-bshor go-’grem).

It is unclear whether these animals are depicted with two or four legs. Differences in the coloration of the animal on the right appear to be due to localized geochemical processes. Antelope are social animals, and on the Changthang they can band together in herds consisting of hundreds of members.

Fig. 41. Another pair of antelopes. These are examples of a fully formed curvilinear vocabulary, in which both the forequarters and hindquarters form circles. Each animal is portrayed with two legs and large triangular hooves. In this variation of animal style rock art, tails are not shown.

Fig. 42. An antelope in a style similar to the specimen in fig. 41, but one that was more crudely executed and less deeply incised in the rock.

This appears to be an example of Protohistoric period art, a perpetuation of the animal style centuries after its original introduction and adaptation in Upper Tibet.

This highly competent carving was deeply cut into the rock. Its horns form sharp angles. Based on the carving technique, execution, wear and patination, this specimen seems to be a true example of Iron Age art, which drew directly from the Eurasian animal style of north Inner Asia. Note the small wild ungulate carving beside the horns of the antelope.

Fig. 44. Four figures in the animal style of Upper Tibet: wild yak (upper), wild sheep or wild yak (upper middle), wild yak (?) (lower middle) and antelope (lower). The matching style, wear and patination of these figures indicates that they comprise a single composition.

These four wild herbivores are adorned with complex volutes. Founded on a rectilinear schema, they are in a style typical of rock art in Ruthok (also see in figs. 36 and 37). The wild yak has a ball tail and prominent humped withers, common motifs in bovid rock art of Upper Tibet. Its body is ornamented with a mass of twisting lines. The body of the upper middle figure is marked with a single corkscrew line. The tiny lower middle figure is situated between its legs. Inside the body of the antelope is a series of volutes.

Less common than either the deer or antelope in the animal style of Upper Tibet is the wild yak (drong; ’brong). Why this is I am uncertain. Perhaps the deer and antelope better captured the spirit of Eurasian animal art and the zeitgeist of which it was a manifestation, sleek herbivores with counterparts across the continent. Last month’s newsletter touches upon the economic functions of the yak in Tibet, and I will not repeat that discussion here. Wild yak rock art in Upper Tibet comes in a number of major approaches, reflecting the great cultural value of this animal. All of the examples shown here are portrayed with four legs, an older esthetic trait retained in animal style art of Ruthok.

Fig. 45. A lone wild yak with S-shaped body adornment. The horns of this yak almost form a full circle, a common motif in wild yak rock art of Upper Tibet.

This wild yak is also distinguished by S-shaped body ornamentation but it is based on a curvilinear schema rather than a rectilinear schema. This particular animal is part of a complex hunting scene that includes at least seven mounted archers and four standing bowman, other wild yaks in various modes of expression, wild caprids and a deer, all carved in the same general period (for more of this scene, see Zhang Zhung, p. 176). These petroglyphs can be dated to the Protohistoric period.

A crudely made scroll is found inside the yak’s body. Save for this motif, this entire composition is of a native artistic persuasion. Note the belly fringe, a prominent motif in Upper Tibetan wild yak rock art. The horse is portrayed running (in the direction of a shadowy yak petroglyph belonging to another composition). This rock art dates to the Protohistoric period.

This specimen has the downward pointing wedge-shaped tail and more rounded body of another major type of Upper Tibetan wild yak rock art. Nearly all other examples of this genre are devoid of body ornamentation. This art is best attributed to the Protohistoric period.

Fig. 49. A wild yak with double volute body motif, humped withers, flat belly and rear end, large ball tail, and belly fringe.

This wild yak is situated on a naturally occurring vertical slab of rock. It is found among other subjects but it seems to form a discrete composition. This piece of rock art appears to date to the Iron Age.

Fig. 50. A large, graceful carving of a wild yak in a similar style to the specimen in fig. 49. The rock on which this yak was cut has been damaged, causing the loss of some of the petroglyph.

This yak has double volute body ornamentation and an elongated tail. It can be dated to the Iron Age, as an example of the original adoption of the Eurasian animal style in Upper Tibet.

Fig. 51. A wild yak (lower) and tiger (upper). These two animals boast many animal style characteristics, as a stylistic culmination of this genre of art in Upper Tibet. Probably Protohistoric period.

These two animal carvings form part of an integrated array of petroglyphs, two of which were featured in the August 2014 Flight of the Khyung (see figs. 13, 14). These carvings cover the east side of a naturally occurring vertical slab of rock. They seem to constitute an elaborate narrative in which clan lore may have played a role. The wild yak has a double volute inside a figure of eight form. The large tail stretches above the rear half of the animal’s body. The belly fringe is long and the legs terminate in points. The eye of the yak is rendered and its long tongue sticks out, a very unusual portrayal. The tall horns curve in and then flare out, another distinctive trait of certain wild yak rock art in Upper Tibet. The tiger (identified by its stripes) is also in the animal style and has an arched body and S-shaped tail. The head of the carnivore is no longer clear. Claws are shown on each of its legs. This tiger appears to be depicted running or leaping.

While not very common, wild caprids, namely argali sheep (nyen; gnyan) and blue sheep (nawa; gna’-ba), are also represented among Upper Tibetan animal style figures. These animals do not always possess the dramatic or iconic elements of deer, antelope and wild yaks, making species identification more difficult.

Fig. 52. The large curled horns of this animal are strongly suggestive of the argali sheep. A somewhat obscured double volute spans the entire length of the body. All four legs are depicted.

Fig. 53. Two standing archers taking aim at a wild caprid and other wild ungulates. Below the archers is a horseman. This is part of the same complex hunting scene as figs. 45 and 46. The body of the wild caprid is adorned with the S-motif. It is shown with all four legs.

Fig. 54. What appears to be two wild caprids or gazelles with scrolls and two legs. The figure on the right with the longer horns turns to look at his companion. All indications are that these two animals form an integrated composition.

The wild ungulate on the left has long, horizontally extended horns. The top portion of the horns has been obliterated through the removal of the rock surface. This may possibly be the rendering of a deer. The volutes, wavy horns and head turned backwards are all traits of the animal style. Single volutes, front and rear, are rare in Upper Tibetan rock art. The equid appears to be mounted by an anthropomorphic figure. It faces in the opposite direction. Although these two animal carvings were made in the same general period, they may not form an integrated composition. This is the only example of animal style rock art in Upper Tibet outside Ruthok. It is found in Guge, another far western district. A reference to this rock art is made in the introduction to Part One of this article.

Fig. 56. A deeply carved wild ungulate with double volute or scroll and head regardant. If this bulky animal is a wild yak, it is one of very few examples in Upper Tibet with the head turned backwards.

The form of the rear leg and its pointed hoof is strongly reminiscent of north Inner Asian animal style art. The head of this quadruped has been heavily obscured. Some of the surface of the rock was removed from the body of the animal but the nature of this ornamentation is no longer discernible.

Fig. 58. A more crudely carved wild ungulate with double volute. Above the animal is a spiral, which betrays the same carving technique, wear and patination as the animal. Other figures on the same boulder appear to belong to different compositions.

Fig. 59. An S-shaped motif in the body of what appears to be an incomplete animal. This must be a wild ungulate of some type.

Fig. 60. A three-horned animal. This may be some kind of deer or antelope. The oval body contains a double volute. Note the smaller, less deeply carved animal style figure to the right. The double volute inside its body is barely visible.

Equids were also created in the animal style in Upper Tibet but they are uncommon. Those without riders are likely to represent Tibetan onagers or wild asses (kyang; rkyang). Even today, onagers, like other large wild herbivores, have sacred qualities and connotations in Upper Tibet. In that region, the wild ass is most closely associated with the class of fierce red-colored deities call tsen (btsan). According to the oral tradition, in ancient times the carcasses of wild asses were used to make coracles for transport on the great lakes. Horses, too, had many special qualities such as being high-value transport animals, mounts of deities and psychopomps.

All equid petroglyphs below appear to be depicted with four legs.

Fig. 61. What appears to be a galloping equid, as identified by its long downward pointing tail, body shape and pointed ears. The underlying sinuous schema and double volute body adornment are sui generis animal style traits. This carving stands alone on a rock panel.

Fig. 62. An equid engraving with a small S-shaped body ornament. The anatomical features captured in this engraving seem to be those of a horse. Flanking this equid are other figures from the same general period (Protohistoric).

Fig. 63. What appears to be an equid embellished with a scroll. This is the only such animal style figure detected at this extensive rock art site in Ruthok.

Fig. 64. A horse and rider carved in an elaborate fashion, constituting another variant of the animal style in Ruthok.

This composition stands in isolation. Unfortunately, it is not in very good condition. Much of the rear of the horse has been obliterated and the form of the rider is now ambiguous. Two or three volutes graced the body of the horse. It is standing on the tip of its hooves and is depicted prancing or trotting, lead leg raised. This composition is comparable with an animal style deer from the Domkhar site in Lower Ladakh (see with L. Bruneau: 2013: “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’” in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28, pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS: http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf Go to p. 123.

There are also carnivores created in the animal style among the rock carvings of northwestern Tibet. It appears that these are tigers, identified through their long curling tails and stripes. They are typically shown with gaping jaws and sometimes in pursuit of prey. Tigers occupy a prominent place in the mythology and religion of Tibet. Among their most celebrated functions is as warrior spirits (drablha; dgra-lha), clan deities (rulha; rus-lha), and remedial deities of spirit-mediums. I hold the opinion that some tiger rock art encapsulates a fact of ancient natural history: these large cats once roamed around western Tibet as an integral part of its ecology. For more tiger rock art in Upper Tibet, see August 2012 Flight of the Khyung. All tigers depicted below have four legs.

Fig. 65. A tiger with the telltale scroll body ornamentation of the Upper Tibetan animal style. This motif obviated the need to carve stripes.

The long tail curls over the rectangular body of the tiger. The mouth is agape and the ears erect. Claws were also carved. Above and below this figure are wild yak petroglyphs but it is not certain that they comprise an integral composition.

Fig. 66. A tiger with interconnected volutes adorning an elongated body. The pointed ear, eye and muzzle of this animal are visible.

As in fig. 65, the tip of the long tail spirals around. The tiger appears to be depicted springing at prey, but in the welter of carvings on this large rock panel it is no longer discernable. Sadly, as with so many other precious archaeological assets in Upper Tibet, this rock art is now the victim of vandalism and inappropriate road construction. The pace of destruction is increasing as Upper Tibet develops at breakneck speed and the region becomes more accessible to outsiders.

This carnivore is chasing a deer, which was depicted in last month’s newsletter (see fig. 26). Both the predator and prey were created with elaborate body decoration consisting of volutes and a series of bowed vertical lines segmenting the body. In the case of the tiger, these represent stripes. Both the tiger and deer are now highly eroded and vulnerable to vandals. This spectacular albeit damaged rock art composition admirably reproduces key features of the Eurasian animal style: complexity and fluidity of design, bellicose pursuits and sheer vitality and boldness.

This style of rock art is comparable to a deer petroglyph at Domkhar in Lower Ladakh and a deer at Tangtse in Upper Ladakh (see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, pp. 123, 129). The deer at Tangtse is also being chased by a tiger, but that tiger more closely resembles those depicted in rock art and on portable objects of north Inner Asian provenance.

This adept tiger carving does not have the volutes or other curvilinear embellishments associated with the animal style. It was however produced in conjunction with such art, as illustrated by the antelope petroglyph above it. The tiger has the same tail curled over the body as other examples we have examined. It also has the rounded form of the animal style. The bold stripes were very competently carved. A chorten, a kind of religious monument, was carved over the head of the tiger. Evidently, its creator had little regard for the earlier art.

This raptor carving appears to possess both animal style and indigenous traits. It is now extremely faint and most details of the engraving have vanished with time. Having been lightly etched into the rock surface, it was especially susceptible to erosion. This geometrically conceived bird has the elaborate body ornamentation and fluency of design of the animal style. Yet, it also possesses indigenous elements such as the angularity of diamond-shaped wings and tail. This petroglyph with its diamonds within diamonds is comparable to a raptor from Yaru Zampa in Central Ladakh, and two older examples from Gertse in Upper Tibet (see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, pp. 144, 145; Antiquities of Upper Tibet, p. 217).

The rock art in this article records the receptiveness of Iron Age northwestern Tibet to the broader esthetic and ideological forces buffeting the Eurasian continent. Both China and Tibet were recipients and propagators of the animal style, which appears to have spread to both territories from adjoining regions of north Inner Asia in the Iron Age (the earliest examples of the animal style may come from the eastern steppes, but this requires further study to be confirmed). The animal style developed endogenously in both Tibet and China, giving rise to distinctive artistic repertoires, reflecting the respective cultural structures and sensibilities of their creators. Nevertheless, these repertoires share stylistic and thematic affinities, as part of the weltanschauung that engulfed Eurasia in the Iron Age.

Next Month: A newly discovered golden burial mask and copper alloy objects in the animal style from Tibet!