November 2013

John Vincent Bellezza

Another Flight of the Khyung is ready for take off! As promised, this month’s issue features two ancient cave sanctuaries recently discovered on the Upper Tibet Rock Art Expedition III. There is also a special report about the spectacular golden burial masks of Upper Tibet and adjacent regions, so please read on.

It is with much pleasure that I announce the publication of an article on antique turquoise written by James Wainwright, an expert in Tibetan beads and other antique objects. His fascinating piece is the final feature in the August 2013 issue of Flight of the Khyung:

http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/august-2013/

James Wainwright maintains a commercial website, Garuda Trading, where interesting Tibetan artifacts can be viewed: http://www.garudashop.com/

Please note: A satellite map of the Sutlej River Valley Citadel can now be found in the May 2012 Flight of the Khyung.

The primordial letter A and the swastika and chorten painted on stone: The ancient cave sanctuary of Darlung Phukpa

Fig. 1. The site of Darlung Phukpa. The two rock shelters are located in the central part of the image.

In the vicinity of Churo, the ancient cave sanctuary featured in last month’s newsletter, there is a similar installation called Darlung Phukpa (Dar-lung phug-pa, 4670 m). This residential complex consists of two small rock shelters perched above a rocky ravine. The lower shelter has been reduced to a few stones still clinging to a ledge just above the base of the reddish limestone formation. If other ancient cave sanctuaries in the region are any indication, much of this ledge may have been enclosed by masonry walls. If so, this site could have supported a fairly large number of people engaged in ceremonial or other kinds of activities. In the ravine below Darlung Phukpa is a small stream, a source of water for the ancient inhabitants and visitors.

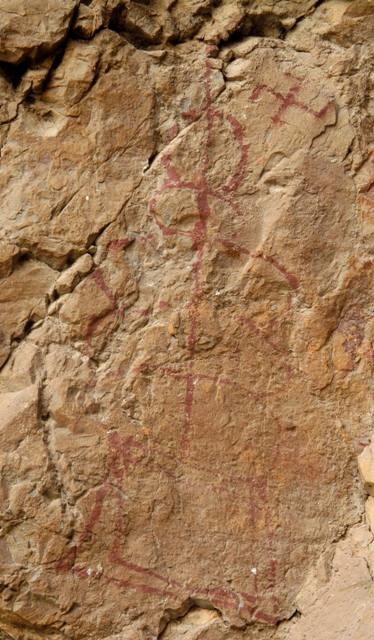

Fig. 2. The lower rock shelter at Darlung Phukpa containing symbols and inscriptions painted in red ochre.

On the north side of the ledge, about 10 m above the ravine, is a recess in the formation around which are the faint remains of a façade (1.5 m x 1.5 m x 1.2 m). On the walls of this shallow cavity are a number of counterclockwise swastikas as well as the Tibetan letter A and the syllable Om painted in red ochre. These pictographs and inscriptions are heavily weathered, not least of all because the rock surface on which they were made is rough and uneven. Poor rock surfaces tend to foster the uneven application of pigments, higher rates of pigment ablation on the more exposed areas, and reduced bonding of pigments to the stone substrate. The ideal limestone surface for painting has a smooth and shiny calcareous veneer, as found at some locations around Lake Nam Tsho.

Despite the lack of an optimal rock surface to paint on, the creators of the red ochre applications still went ahead and modified the tiny cave with symbols of their occupation of the site. Why did residents or visitors to Darlung Phukpa and other cave sanctuaries in the region feel compelled to mark them with lasting reminders of their presence? As noted in previous newsletters, there appear to be two major reasons for this art and epigraphy, both of which are predicated on rivalries or tensions between competing religious groups. Briefly, they are:

1) The desire to distinguish one religious sect from another operating in the same area.

2) The need to physically and ritually secure sites for use by a specific sect or cult.

Fig. 3. Counterclockwise swastika and branching geometric design (each around 15 cm in height), located in a crevice of the lower rock shelter, Darlung Phukpa. The identity of the geometric design is unclear. It may possibly represent a tree.

In Darlung Phukpa all symbols and inscribed letters added to the caves appear to have been the handiwork of non-Buddhists. They include counterclockwise swastikas, which are associated with practitioners of religious traditions that underlie the formation of systemitized Bon, circa 1000 CE. It appears that sectarian distinctions associated with the direction of the swastika developed in the imperial period (circa 650–850 CE), a byproduct of religious strife and differentiation between Buddhists and those maintaining a religious order based on older or hybridized traditions. Unfortunately, there is still no reliable and economical way of scientifically determining the age of rock art and inscriptions, which could be used to establish a verifiable chronology in order to test this historical observation.

Fig 4. Three examples of the Tibetan letter A written in an archaic script (each around 20 cm in width), Darlung Phukpa. These letters are highly worn and the pigment has undergone at least some color change.

Fig. 5. The upper specimen of the letter A. Rather than constituting an inscription, this letter might be better seen as a magic symbol or distinguishing religious emblem.

Fig. 6. The lowermost letter A in the group of three, which like its counterparts, is rendered in an unusual fashion.

There are at least three different examples of the Tibetan A in the lower recess of Darlung Phukpa. This letter A belongs to an archaic paleography predating the 11th century CE. Attribution to the imperial period seems best indicated. However, it is possible that this letter A was adopted from the Indic tradition of scripts at an even earlier date, for use as a mystic symbol or cipher. Such an early adoption, if it is so, might go some way to explaining the scripts known as maryik (smar-yig), which the Bon religion claims were used in Zhang Zhung long before the imperial period. However, no epigraphic evidence for such a system of writing has yet surfaced in Upper Tibet (or in other regions of Tibet). If maryik existed in any form at all, the archaic letter A inscribed at various locations in Upper Tibet is the likely candidate.

Fig. 7. Three counterclockwise swastikas, which are situated below the three examples of the letter A. The largest of these is 14 cm in height. These swastikas are extremely eroded, a process encouraged by the rough texture of the rock. The lowermost swastika is mostly obliterated (only the top portion is visible).

As they possess the same hue and agglutinative characteristics, the examples of the letter A and the three swastikas below them were apparently made with the same type of red ochre. They also exhibit a similar degree of pigment ablation, suggesting that these pictographs and inscriptions were made in an analogous timeframe.

Fig. 8. The remains of a counterclockwise swastika painted in red and yellow ochre. There are a number of examples of bichrome swastikas in this region of the Changthang. Although heavily worn, the pigments are of a brighter hue than the swastikas in Fig. 7. Probably made with red ochre deviating in composition and rendered in variable styles, these two sets of swastikas may have been created in different periods of time (with the bichrome specimen probably being later).

There are also two or three other anticlockwise swastikas on the walls of the lower rock shelter. The multiple application of this seminal symbol hints at a prolonged or concerted effort to make manifest the religious ownership of Darlung Phukpa. With the construction of a local Nyingma sect monastery, Buddhism was well established in the region by the late 11th century CE. Therefore, the pictographic swastikas were probably created before that time.

Fig. 9. The Tibetan syllable Om. This well-worn inscription is rendered in an old style script, as found at other Upper Tibetan locations as well. However, the paleography does not seem as archaic as examples of the letter A examined above. Given the calligraphic form and location of the Om, it is best assigned to the same non-Buddhists or ‘bonpo’ who produced the other ochre applications at Darlung Phukpa. This inscription can be dated to the early historic period (650–1000 CE). This Om may have had magical, ritual, doctrinal, or social affiliative connotations for its maker and users.

It is quite clear from the rock art and epigraphy of Darlung Phukpa that this installation was not reoccupied by Buddhist practitioners in any major or lasting way. Had it been, evidence of their tenure would surely be present at the site. At minimum, there would be signs of tampering with the early symbols and letters, but there is no evidence for this. Darlung Phukpa is a relatively small site that may never have had more than a handful of people in residence. Therefore, it may not have been seen as particularly worthwhile for the Buddhists reinhabit it. It may also be that in the Buddhist era there was not a sufficient population base or economic resources to reoccupy all of the ancient cave sites in the region. Moreover, some of these sites must have been considered inauspicious or haunted, associations that have lingered to the present day. Places like Darlung Phukpa are usually avoided by present day herders for fear of the danger emitting from them.

Fig. 10. The much larger upper cave shelter of Darlung Phukpa. Note the ruined stairway leading up to the masonry front of the cave. The narrow entrance to the shelter with its stone lintel and the random-rubble stone slab wall courses of the façade are typical of archaic era residential constructions in Upper Tibet.

The upper cave at Darlung Phukpa is considerably larger and the stonework around it in significantly better condition than the lower rock shelter. The upper cave is elevated approximately 20 m above the ravine. The remains of a stone stairway lead up to it, but the lower portion of these stairs is no longer intact. A cliff face has to be ascended in order to access the remaining stairs. I deferred from scaling this cliff – I simply was not in the mood that morning for a somewhat risky free climb. Having not been to the upper cave, I have no way of knowing what is inside it, if anything, as the interior is blocked from view by the stone façade.

Fig. 11. On the rock formation above the façade of the upper cave a counterclockwise swastika and the letter A are visible.

What can be seen from below is that a large counterclockwise swastika and letter A have been painted on the ceiling of the upper rock shelter. These were made using a white pigment and exhibit the same techniques of execution and levels of wear, suggesting that they form an integral composition made by the same individual. The letter A is of a standard script (dbu-can) still used to write Tibetan today. This may indicate that this composition is of a more recent date than those in the lower rock shelter. Around 400 years elapsed between the introduction of writing in Tibet in the 7th century CE and the definitive establishment of Buddhism in the region in the 11th century CE, providing ample chronological leeway for the evolution of Tibetan scripts to be reflected in Darlung Phukpa.

The swastika and letter A appear to be the handiwork of the Bon religion or that of its predecessor, the local cult groups known generically in Tibetan as bon as well. The letter A in particular may have been associated with practitioners of Dzokchen (Rdzogs-chen), a profound philosophical perspective on reality and system of mind training. For a general discussion of Bon and bon, see last month’s newsletter.

The ancient art and architecture of Dokhor Phukpa

Fig. 13. The limestone formation with the Dokhor Phukpa cave sanctuary and ruins. The cave site is visible on the left side of the photograph, a vertical slit in the formation above the second rock terrace.

Dokhor Phukpa, another ancient cave sanctuary in the Central Changthang, is situated about 100 m above the lake basin of Mating Tingmo (Ma-ting ting-mo). The site consists of a single cave facing southeast (4700 m). The final approach to the cave is via a steep fissure around 15 m in height. In this fissure are the remains of stone steps, and near the mouth of the cave there are a couple crumbling revetments that supported these steps and a landing.

The cave (9.5 m x 3 m) has a level floor and high ceiling. The erstwhile importance of this cave is attested in a collection of pictographs found on its walls. This rock art is all non-Buddhist or bon in character. Most or all of it is datable to the early historic period. Although Dokhor Phukpa may have had a very long tenure of human occupation, beginning perhaps in the 7th or 8th century CE, it was singled out for artistic treatment. The chronology of this rock art is similar or identical in other cave shelters of the region. To reiterate, sectarian or political factors were probably involved in the creation of the artwork.

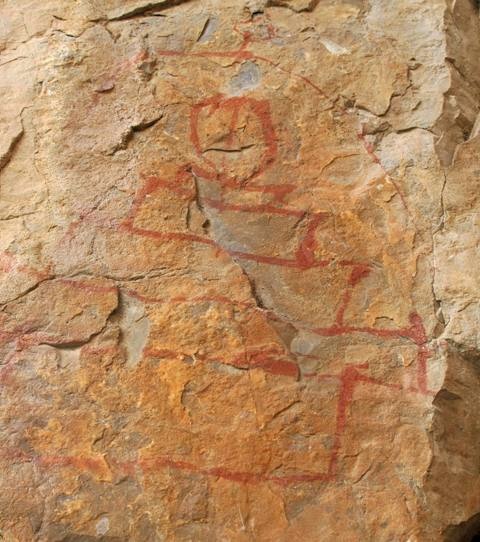

Fig. 16. A highly unusual shrine or chorten pictograph (20 cm in height), Dokhor Phukpa. It was painted with staggered tiers and a tiny round midsection (bum-pa) crowned by a prominent horn-like finial.

On the east wall or right wall, quite deep inside the cave, there are two curious pictographs portraying a shrine and anthropomorphic figure. The shrine is of a peculiar design and it is uncertain whether it represents a chorten or a more rudimentary religious construction such as the tenkhar (rten-mkhar) or sekhar (gsas-mkhar). The manner in which each succeeding tier is offset from the central axis in opposite directions is unique. One wonders if anything like this was actually built or if this was just the fancy of the artist. The horn-like finial is associated with monuments of the archaic cults of Upper Tibet and later with the Bon religion. This pictograph has undergone much ablation and pigment dissolution.

Fig. 17. A red ochre human figure (23 cm in height). Its head, eyes, arms and legs are all discernible, despite the ablation of the pigment over the centuries. The figure is dressed in a long robe with a sash or belt tied around the waist. Also note the V-shaped neckline or collar. The left arm of the figure is either gesturing above waist or holding a long object with a round end. The loss of pigment prevents us from determining with accuracy the aspect of the arms and hands.

In close proximity to the shrine is an anthropomorph exhibiting comparable pigment and wear characteristics, suggesting that they were painted in the same general time period. In both rock paintings, the red ochre has faded considerably over time. Pictographs of anthropomorphs of this size or larger are not very common in Upper Tibet, adding to the value of this shadowy figure. Its identity, whether human or divine, cannot be determined. One could speculate in a variety of ways, seeing a priest, ancestral hero or god in this portrayal, but speculation it will remain. That this figure is found next to the representation of a shrine and that all other pictographs in Dokhor Phukpa are of a religious nature, strongly suggests that it too has a numinous or sacred identity. The shrine and anthropomorph appear to date to the early historic period, but in the absence of hard scientific data, a somewhat earlier date can also be entertained.

Fig. 18. The third pictograph on the east wall of Dokhor Phukpa. This elementary shrine or chorten has a bulbous top and three tiers (the middle one appears to be very narrow). The shrine may have been composed with a finial and/or spire but not enough pigment adheres to the rock to be certain. This pictograph dates to either the protohistoric period or to the early historic period.

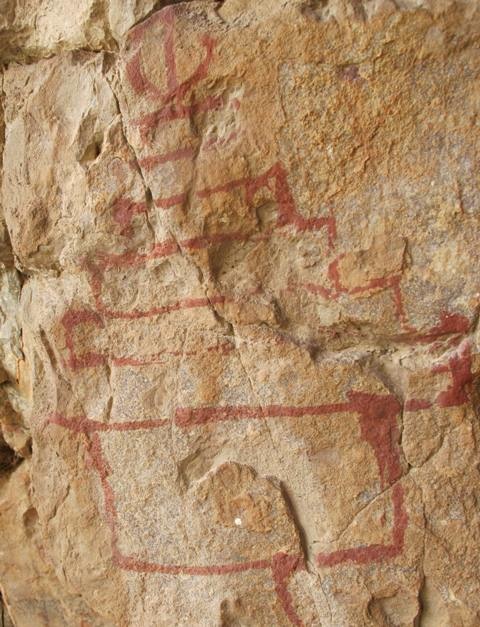

Just outside Dokhor Phukpa, on the west or left wall, are six red ochre pictographs of archaic chortens or possibly other types of shrines. Due in part to the fairly poor quality of the rock surface, these paintings are not well preserved. There are also three counterclockwise swastikas on the west wall of the cave, reinforcing the non-Buddhist identity of the site and signalling its occupation before the 11th century CE. Caves such as Dokhor Phukpa and Darlung Phukpa may have been residential and religious sites since deep antiquity, but it is only later that they came to be embellished with red ochre rock art and inscriptions. Much of this art and writing is attributable to the early historic period and probably much of it more specifically to the imperial period. Like Darlung Phukpa, Dokhor Phukpa was not modified with Buddhist inscriptions and drawings.

There are many caves in the region, but Buddhists in the second millennium CE concentrated on only a few of them. The abandonment of most caves after 1000 CE suggests that the population of the region had diminished or that alternative domiciles (such as the black yak hair tent or freestanding buildings at lower elevation) had become the cultural norm for all segments of Upper Tibetan society.

Fig. 19. Two of the archaic shrines and a swastika on the west wall of Dokhor Phukpa (all figures in middle of image).

Fig. 20. An archaic chorten with rounded stages and a central axis (approximately 45 cm in height). This depiction has a small spherical midsection or bumpa. To the right is an anticlockwise swastika that is part of the same composition (as evidenced in the style of execution, pigment type and physical state).

Fig. 22. Another archaic chorten on the west wall of the cave. Due to its position on a sheer vertical wall above arms reach, the size of this pictograph and others in close proximity could not be measured (they range between 35 cm and 55 cm in height). This particular specimen has five steps or tiers and a tiny bumpa. No spire or finial is visible. Such depictions are intermediate in form between rudimentary stepped shrines and the more complex architecture of the multitiered chorten still recognizable in contemporary structures.

Fig. 23. A highly eroded archaic chorten or other type of shrine of at least five tiers located on the west wall of Dokhor Phukpa.

Fig. 24. A chorten or more primitive shrine of seven tiers topped by a three-pronged finial, a crowning ornament now associated with Bon chortens.

In addition to the shrines shown above, there is a smaller one in close proximity but very little of it remains adhered to the rock. Just the outline of parts of its base and a circle are discernible. Perhaps this specimen was never completed. Also, inside the cave quite high up on the west wall, there is a crudely rendered red ochre shrine comprised of three tiers.

Fig. 25. Fellow explorers descending down the steep chute from Dokhor Phukpa. The walls of a ruined structure can be seen on the grassy slope below.

Fig. 26. The ruined limestone hulk below Dokhor Phukpa. The cave and access chute are situated directly above the carcass. This structure is underpinned by a prominent revetment.

In addition to the cave with red ochre pictographs, there are the remains of a relatively large structure directly below it. This structure was established on slopes that drop off steeply into the lake basin below. As this ruin has been reduced to the revetment and lower walls only, very little of its architectural character is appraisable. Nonetheless, the massive and well built revetments and wall fragments allude to a significant edifice having once stood on this site. Alternatively, it is possible that this was just some kind of elaborate platform, but this seems less likely.

It is difficult to see how the ruin and cave cannot have been closely connected. Like the cave, there is no physical evidence for a Buddhist presence at the ostensible building. If Buddhists had built or used this structure they surely would have made their presence known in the way of inscriptions or inscribed plaques. Having a cave with explicit signs of the archaic religion hovering above would not have been particularly comfortable for Buddhist residents, unless special ritual measures were taken to subdue or neutralize Dokhor Phukpa. And if such measures were taken there should be definite physical evidence of them available for inspection. Furthermore, there are no Buddhist legends or folklore associated with the site, unlike other places in the vicinity where the Buddhist monastic tradition took root.

Fig. 27. The ruins of what may have been a building of significant size. Standing inside is one of the members of the reconnaissance party. To the right is the lake of the goddess Mating Tingmo. The ancients certainly picked a great location for their construction.

As the edifice below Dokhor Phukpa seems to have a non-Buddhist identity, it can be probably be dated to prior the 11th century CE. What the functional relationship between it and Dokhor Phukpa was is hard to determine. It might be conjectured that a building was used for domiciliary purposes and the cave as a sanctum or temple. If so, this would demonstrate that the site had complementary residential and ceremonial functions. These twin functions are very common in archaic sites all over Upper Tibetan. Frequently, buildings came up around caves, which served as the innermost or most sacred space of sites. Many of these structures adjoin the caves whereas others were founded within a few tens of meters of them.

Fig. 28. The forward revetment and wall of the ostensible building. Note the orange climax lichen clinging to the stones. In the background two members of my team take measurements.

Fig. 29. The north (foreground), east (left) and west (background) walls of the structure. These walls were built of limestone blocks, some of which appear to have been roughly hewn into shape.

The heavily built structure below Dokhor Phukpa measures 12.4 m (north-south) by 8.5 m (east-west). The east wall of this apparent building extends 10 m north of the structure, enclosing some of the surrounding rock formation. This seems to have protected access to Dokhor Phukpa, enhancing the importance of the cave and more closely linking the two places.

The forward wall of the structure is up to 2.5 m in height on the down slope side and only 50 cm high on the uphill or inner side, the difference in height being made up by the revetment. These walls have a dry-mortar random-rubble fabric and were constructed using variable-sized limestone blocks up to 1 m in length. The freestanding walls are 70 cm to 80 cm in thickness. The south wall at the east corner is 2 m high, decreasing in height as it runs uphill. It continues 4 m west of the main structure, elevated 3 m above it on boulders. This extension may possibly have been part of a structure with defense or ceremonial functions. The west / rear / uphill wall of the building is deeply set into the slope, rising no more than 20 cm above it. The interior of the structure is now sloping but it must have been level originally.

In the basin directly below Dokhor Phukpa is a series of springs. These would have provided an ample source of water for the residents of the site. Almost certainly the lake as a sacred body of water was a main attraction for those who built the structures of Dokhor Phukpa. Like Dokhor Phukpa, other archaic residential sites and cave temples in Upper Tibet were often positioned to overlook a large expanse of water to the east.

The name of the lake goddess, Mating Tingmo, is derived from the Zhang Zhung language, as is her mate’s, the mountain Tanggyung (Stang-rgyung). It thus appears that this pair of mountain and lake deities has archaic origins, their names persisting in a Buddhist dominated religious environment. Such are the historical continuities often encountered in the religious and mythological traditions of the Changthang. Nevertheless, Mating Tingmo is now seen as belonging to the tanma (brtan-ma) group, goddesses that have been heavily Buddhacized. If she was also worshipped by archaic religious practitioners of the area, the mantle of tradition surrounding her would have been considerably different and probably much richer than in more recent times.

Visages of the past: The golden burial masks of Upper Tibet, the Himalaya and northwestern Xinjiang

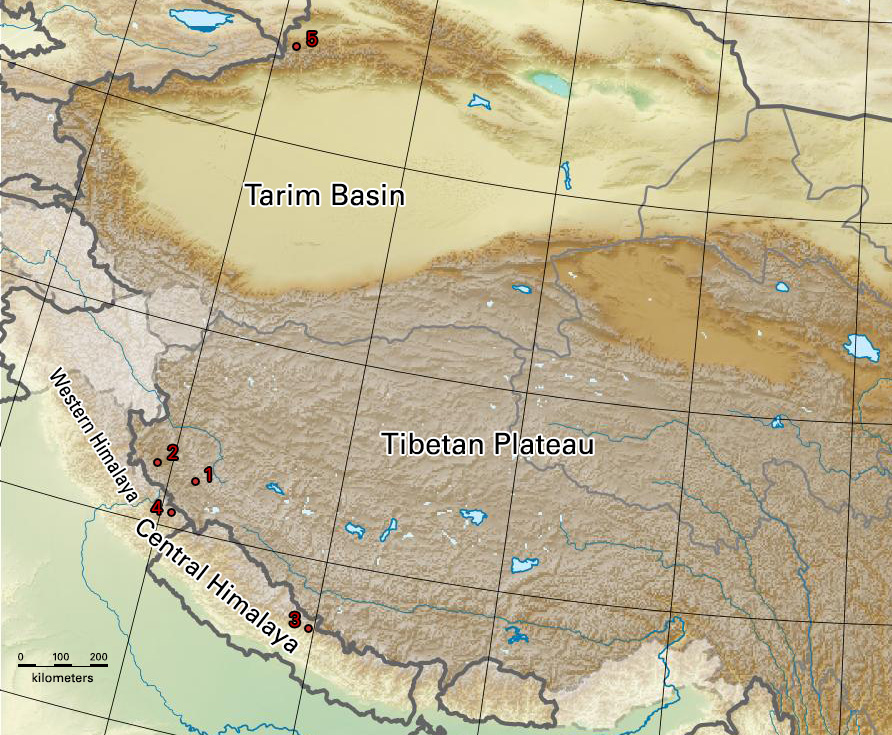

Map: Locations where the golden burial masks of Upper Tibet, the Himalaya and northwestern Xinjiang were discovered. 1. Gurgyam; 2. Chuthak; 3. Samdzong; 4. Malari; 5. Boma Cemetery.

In 2012 and in 2013, Chinese archaeologists under Dr. Tong Tao opened seven tombs in Gurgyam (Gur-gyam), in southwestern Tibet. Gurgyam is situated at the junction of two ancient districts: the badlands of Guge (Gu-ge) and the more open plateau of Chari Tsukden (Bya-ri gtsug-ldan). Gurgyam is only 1 km from Khardong (Mkhar-gdong), the ruined stronghold that may be synonymous with Khyunglung Ngulkhar (Horned Eagle Country Silver Castle), the capital of Zhang Zhung until the mid-7th century CE.

The excavations took place right in front of Gurgyam monastery. The Bon monks here do not seem to mind living on or in close proximity to an ancient burial ground. In fact, they take much pride in their past and what is being discovered in their midst. The monks have assumed responsibility for preserving the artifacts and bones being unearthed from the cemetery. They have installed glass display cabinets in their assembly hall effectively turning part of it into a museum.

It is said that a proper museum will be built in Ngari prefecture to permanently house the finds from Gurgyam. I laud the decision of the Chinese excavators to secure grave objects recovered from the site locally. Not least of all, the climate there is amenable to their preservation.

The stone-lined tomb chambers covered by fine, unconsolidated sandy soils were found at a depth of approximately 4 m. The initial discovery of a tomb at Gurgyam was made accidentally in 2005. A human bone sample from this first tomb, which was excavated in 2006, has been AMS dated to 220–350 CE. For reports on this excavation and the objects recovered, see the October 2010 and April 2012 issues of Flight of the Khyung. All the excavated tombs have been refilled. It is reported that up to nine human skeletons were found in a single tomb. However, we will have to wait for a detailed scientific report from the excavators to better know what has been discovered and to accurately understand the significance of their work. For links to press releases written by Tong Tao describing the discoveries of 2012, see the September 2012 issue of Flight of the Khyung.

In 2012, the Chinese found a wide variety of artifacts in the tombs they opened that year. Among those now displayed in the Gurgyam monastery are gilt silver (?) sleeves with an embossed design consisting of four leaves or petals. Some of the sleeves appear to have a wooden backing. A number of incomplete strings of turquoise were also unearthed. These tiny beads (around 5 mm in diameter) are in surprisingly good condition and retain a bright turquoise blue color. Interspersed among the uniform sized discoid turquoise beads are red beads (coral?) of the same size and shape. Turquoise beads of this type and size are still made for the Tibetan market today. Not only does this discovery confirm that turquoise has been used as an ornament in Tibet for at least 1500 years, it demonstrates that the color and stone combinations favored in contemporary times have an ancient precedent.

Also in 2012, an equid (horse) skull was recovered from one of the tombs of Gurgyam. This skull appears to have been a constituent part of funerary rites associated with the burial. In archaic Tibetan death rituals, horses were used to mystically transport the dead to the afterlife. The equid skull from the tomb may well be part of the sacrificial remains of one such psychopomp animal. Other species of animal bones have also been found in the tombs of Gurgyam. Hopefully, a detailed inventory and analysis of these osteological remains will soon be released by the Chinese.

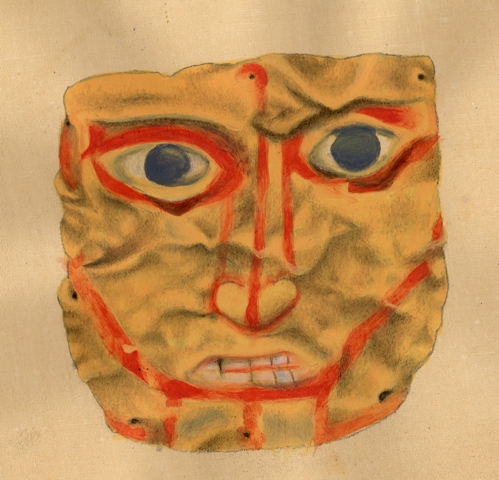

Fig. 30. The golden burial mask of Gurgyam. This mask is a miniature (4.2 cm x 4.2 cm). Eyes wide open and teeth bared, the face conveys a quality of starkness or candor. The perforations along the edge of the mask indicate that it was attached to something else. Painting by Lingtsang Kalsang Dorjee.

Unquestionably, the most spectacular object taken from the Gurgyam tombs in 2012 is a golden mask. This burial mask features a human face and employs a rather elementary repoussé technique enhanced with red, black and white paint to more clearly render the eyes, nose and mouth. It appears to have been fashioned from a thin sheet of silver to which gold leaf was applied. The teeth are also depicted on this is mask. The small size of the mask suggests that it was not used to cover the face of the corpse. Thus this object may have had an alternative placement in the tomb.

We must await Chinese archaeological reports for confirmation of the age of the Gurgyam mask. The tombs excavated by the Chinese archaeologists in 2102 and 2013 are located adjacent to the burial from the 3rd to 4th century CE excavated in 2006. Although all these burials are of the same type and tradition, considerable time differences may possibly separate them. It is possible that successive members of a royal, noble or ministerial lineage are interred in adjacent tombs, thus a number of different generations could be represented in the burials. Be that as it may, all the excavated tombs of Gurgyam predate the 7th century CE.

In the archaic funerary rites, as recorded in Tibetan literature, there is an object known as sershe (gser-zhal) or ‘golden visage’. This object functioned to enshrine and protect the spirit of the deceased during the evocation ritual of the funeral. In more recent times, the sershe was a painting or thread-cross, but a more literal interpretation of its form in the ancient period seems indicated. Although, it cannot be categorically stated that the sershe and golden mask of Gurgyam are one and the same, this is the strongest assignment of function in hypothetical terms. If the Gurgyam mask is indeed a sershe, it signifies that it is a likeness of the deceased.

For more on the sershe, see the books Zhang Zhang: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet and Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet. For bibliographic information and synopses, see “Books”: http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/books/

For more on golden masks recently discovered in Tibet, high Himalayan regions and other locations, see the October and November 2011 issues of Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 31. This intricately designed golden burial mask was unearthed in Chuthak (Chu-thags), Guge. This object is 13.5 cm in height. Like the Gurgyam specimen, the Chuthak mask was discovered in the Sutlej valley drainage system; the two sites not more than 120 km distant from one another. The Chuthak mask also appears to be fashioned from gilt silver plates. Note the engraved zoomorphic motifs (birds and caprids) and tiered structures of the upper plate. Photo courtesy of Lin Luhui, the archaeologist who discovered this exceptionally important Tibetan cultural artifact in 2011. Lin Luhui estimates that the Chuthak mask is around 2000 years old.

The long, straight, narrow nose depicted on the Gurgyam mask is intriguing. Also, the eyes of the Gurgyam mask are perhaps more round than if they were of a pair having the epicanthic folds of east Asians. The face portrayed seems to have ‘Caucasian’ features, as represented among Indian and Eurasian populations. I have made these same observations for the elaborate burial mask recently discovered in Chuthak (see Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet). Nonetheless, these observations on the anatomical elements of the Tibetan masks are unverifiable in themselves. So, let us look a bit further afield to see if we can shed a little more light on the matter.

Fig. 32. Burial mask unearthed from a tomb in Samdzong (Mustang), Nepal. This mask was fabricated using the same repoussé technique as the Gurgyam specimen. It also exhibits the same degree of craft refinement. The Samdzong mask appears to be made from a sheet of silver upon which gilding was added. My colleague Mark Aldenderfer has indicated to me that this funerary artifact can be attributed to the 4th or 5th century CE. Photo courtesy of Mark Aldenderfer.

Although the Samdzong burial mask is much larger (15 cm in height) than the Gurgyam specimen, both of them present similarly rendered human faces. In the photograph small traces of red paint can be discerned around the eyes, nose and mouth, a decorative technique used on the Gurgyam mask. The teeth also appear to have been depicted. Its crescent-shaped mouth, oval eyes and elongated nose also recall those of the Gurgyam example. Therefore, we have two masks produced using the same methods of manufacture with probably the same materials and exhibiting similar countenances. Both masks also have perforations around the edges. On the golden mask of Chuthak these holes were used to fasten a textile (burial shroud?).

The masks of Gurgyam and Samdzong were discovered in locations nearly 400 km apart, the former on the high plateau near the headwaters of the Sutlej river, and the latter on the southern fringe of the plateau in the Kali Gandaki valley system. Both of these regions have canyons with caves but Gurgyam is considerably higher and more continental. In these distant regions, one well north of the Great Central Himalaya range and one within its grasp, similar golden burial masks were deposited in tombs along with corpses and a range of other material objects.

It is interesting to observe that although the Samdzong mask is most like the one from Gurgyam, Gurgyam is geographically much closer to Chuthak, the site where the fancy Guge mask was found. Not only does this indicate that different style golden burial masks were used in Upper Tibet, it suggests that common cultural links existed over a much wider area encompassing Mustang, and as we shall now see, even a cis-Himalayan region.

Fig. 33. Golden burial mask discovered in Malari, Uttarakhand, India. It is estimated to be 2000 to 2300 years old. Photograph courtesy of Vinod Nautiyal, one of the archaeologists responsible for the excavations that led to the recovery of this mask.

Several years ago another golden burial mask was discovered by Indian archaeologists in Malari, a high Himalayan village in Uttarakhand. As the crow flies this location is only 100 km from Gurgyam, but it sits squarely on the opposite side of the Himalaya. This repoussé mask was skilfully fashioned apparently from the same materials as the other three specimens discussed above. The eyes were styled not unlike those of the Gurgyam mask, whereas the nose with its rounded nostrils is more like the nose of the Guge specimen. The tapering outlines of the Guge and Malari faces are also very close in form. Like other masks examined above, there are perforations along the edge of the Malari example, indicating that it was ritually used and deposited in the tomb in a similar manner. The Malari mask is the only one found thus far in a cis-Himalayan location.

Malari is located in the Central Himalaya, not far from the crest of the range, a region now inhabited by the Marcha, one of the so-called seven Bhotiya tribes of Uttarakhand. The ‘Bhotiya’ tribes share many linguistic and cultural traits with Tibetans. Well into the 20th century, they retained certain funerary customs analogous to archaic types found in Tibet.

Given the very particular nature of the four golden masks in terms of their manufacture and design, we can infer that conceptions behind their use and deployment resonated between peoples of the four regions. Determining how close the respective funerary rites might have been, however, requires a much wider comparative exercise, drawing in the full spectrum of artifacts from the burials (despite the significance of this one parallel). Hopefully, the archaeological data needed for this avenue of research will be published in due course.

At this juncture, we do not know if the burials of Gurgyam, Guge, Samdzong and Malari were carried out by people sharing an identical culture, language or ethnic makeup, or if there were significant variations between them. I suspect the latter scenario is the most plausible one, reflecting the rich ethnographic mosaic still present in the region. Moreover, if the estimates of the age of the respective masks holds up to more rigorous scrutiny, they indicate that the Chuthak and Malari specimens predate the Gurgyam and Samdzong masks by as much as several centuries. Time also tends to be modifier of cultures, exerted through the forces of endogenous development, altered physical environments and contacts with extraneous peoples and technologies. This process of evolution unfolds over the centuries as cultures adopt new forms and patterns. Hence, the manufacture of the masks in different periods may have also influenced their design. What can be confidently stated is that the inhabitants of the four regions partook of the same burial custom of using golden masks in their tombs. This could have come about through any number of factors related to trade, war, diplomacy, missionary activities, etc., or through antecedent cultural and religious traditions inherited in common by the mask-making regions.

The location of Samdzong and Malari places them within a geographic sphere in which early connections to peoples of the Subcontinent are indicated on a number of grounds (including archaeological and literary evidence). Perhaps the cosmopolitan array of material goods discovered in pre-Buddhist tombs of Mustang reflects a population of mixed origins in that region, sharing genes of both Bodic and Indic (and possibly Austroasiatic) groups. Nonetheless, we must await hard scientific evidence to test this hypothesis. While it is only conjecture at this point, an admixture of genes from the Subcontinent in the burial in which the Samdzong mask was found could possibly explain the artistic portrayal of the face. The same may be true of Malari. The amalgamation of genes from the Subcontinent are indicated in the current population of the region, perhaps mirroring to some extent the ancient genetic composition of Malari as well.

Interestingly, all throughout western Tibet, there are folktales attributing archaic burials, fortresses, temples and ceremonial sites to the Mon. Mon is a non-specific ethnonym referring to various cultural and caste groups of the south side of the Himalaya. The legends of the Mon prevalent in Guge and Gurgyam possibly reflect early cultural and ethnic links between these regions and cis-Himalayan ones such as Uttarakhand and Mustang. The ancient Mon (also called Skal-mon) of western Tibet are associated with Central Asia too, another potential source for the artistic inspiration behind the masks.

Fig. 34. The golden mask of Boma Cemetery, northwestern Xinjiang. This image is widely available on the worldwide web. Photo courtesy of Administration Commission of Cultural Relics of Xinjiang.

Indeed, a golden burial mask has been discovered in northwestern Xinjiang, the Boma Cemetery specimen.* This mask was part of an elite burial and is thought to date to circa the 5th century CE, placing it, or so it seems, in the same era as the golden masks of the Himalaya and Tibetan plateau. The Boma Cemetery specimen also appears to be a gilt silver repoussé production. However, the face has a deeper relief and is more intricately fashioned with add-on eyebrows and moustache. It also has a band along the edge of the face studded with garnets. Despite major differences in presentation, the facial features of the northwestern Xinjiang mask share stylistic affinities with those of the other specimens we have been examining.

* For the Boma Cemetery golden death mask, see one or more of the following websites:

http://www.penn.museum/silkroad/gallery.php

http://www.pasthorizonspr.com/index.php/archives/11/2010/secrets-of-the-silk-road

http://aratta.wordpress.com/tokariere-ie/

http://historizo.cafeduweb.com/lire/12461-controverses-autour-une-beaute-momie-xioahe.html

http://archive.archaeology.org/blog/yingpan-mans-fabulous-wealth/

In terms of fabrication and appearance, the four low-relief masks of Tibet and the Central Himalaya correspond more closely with one other than they do with the example from Xinjiang. The differences between the group of low-relief masks and the Boma Cemetery mask probably correspond with a greater degree of cultural separation between them than the various regions of the former group experienced.

Although the Gurgyam, Guge, Samdzong and Malari masks appear to be closely related, a cultural interrelationship with northwestern Xinjiang is indicated. Such an affiliation is strengthened by artistic parallels between grave goods discovered in the Tarim Basin and ‘animal style’ rock art on the western Tibetan plateau.* These artistic and material affinities allude to certain ideological links related to death, which spread over a broad area extending north of the Kunlun mountains and south of the Himalaya via the Tibetan plateau.

* See Bruneau and Bellezza, forthcoming (December 2013). “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’ in Revue d’etudes tibétaines vol. 28, pp. 5–162.

This article has examined five golden burial masks of similar fabrication and probably of comparable antiquity. Whatever the precise cultural and ethnic interconnections between the users of the golden masks of Inner Asia and the Himalayan rim-land, a certain cosmopolitan tendency in death rites is observable. This commonality in funerary systems may possibly be predicated on longstanding cultural historical precedents. The Tibetan archaic funerary ritual texts with their narratives set in the distant past suggest so much. Who the carrier of this tradition was remains to be determined. If the folklore and historical literature of western Tibet is of any relevance, people of Himalayan or Central Asian origin may have been responsible for its dissemination over a wide area. On a purely speculative basis, one might therefore suggest that the ruling elite of western Tibet of the early first millennium CE (protohistoric period) may have been partly or wholly of foreign origins, a group that came to be known as ‘Mon’ or ‘Mon-pa’.

The discovery of golden death masks in Greece and the Balkans dating to the second half of the first millennium BCE may also, in some way or another, underline the antiquity of links between Inner Asian and Himalayan funerary rites. We shall see. Advancement in any field depends on evidence and as it mounts more will become known about the burial masks of the Tibetan plateau.

In 2013, decidedly fewer grave objects were revealed in the excavation of four more tombs at Gurgyam by the Chinese. These artefacts include iron spearheads and other highly deteriorated iron objects. Ceramics have been discovered in all the tombs of Gurgyam. This year an attractively shaped unglazed reddish pot with a long spout and bridge connecting it to the neck of the vessel turned up. The bridge is decorated with three incised circles or eyes, a common motif seen in a variety of media of ancient Tibetan origin. This vessel remains unbroken.

As the excavations of 2013 appear to have been less productive, perhaps this is a good time for Chinese archaeologists to pause and gather resources for a more rigorous regimen of exploration. Hopefully, future work will better reflect the current state of scientific progress in the field of archaeology. A meeting of Chinese archaeologists and other specialists held in Ngari this year seems to have reached the same conclusion. Thus we should have something to look forward to, with new insights into ancient Tibet perhaps just a stone’s throw away.

Next month: One of the greatest panels of rock carvings in all of Tibet!