November 2012

John Vincent Bellezza

Please join the horned eagle of Tibet for more great exploration! This month’s Flight of the Khyung swoops down through the very layers of history as revealed by the pullulating rock art of Upper Tibet. Our journey promises a new perspective on the course of culture over many centuries.

Palimpsests: the superimposition of images and inscriptions

Much can be gleaned about the chronological makeup of rock art when stone surfaces are reworked and amended. In rock art theatres the world over, it is commonplace to find that paintings and carvings have been added on top of preexisting artwork. Sometimes three or more strata are discernible as artists from different periods attempt to efface, emend or embellish what came before. The situation is not any different in Upper Tibet. In places where suitable rock surfaces were at a premium, carvers and painters often squeezed in new compositions, partially obscuring the handiwork of earlier artists. Even in some locations with ample expanses of good rock for painting and carving, artists and scribes would purposely cover up the creations of others.

This concern or disregard by turns with past symbols and subjects appears to have manifold causes. Generally speaking, impetus for change can come from many sources: new ideas, technologies and peoples paramount among them. In Upper Tibet these overriding forces appear to have manifested themselves in the introduction of metallurgy, the appearance of the riding horse, the advent of Buddhism, and the various sectarian struggles of the last millennium. Cultural evolution is like a river that changes in character as ever more tributaries enter it. These waters merge to form a new river, the sum total of its various sources. Palimpsests chart this cultural river.

As for affective factors involved in the superimposition of new rock art, both positive and negative ones can be envisioned. Past deeds, customs and beliefs as expressed in rock art can be both an object of veneration and a stimulus for fear and disgust for those who come later in time. In the text below we shall examine how these physical and psychological forces in theory may have been articulated in the carvings and paintings of Upper Tibet.

The addition of rock art on top of preexisting compositions is not a new phenomenon in Upper Tibet. The creation of palimpsests goes back to the early historic period (650–1000 CE) and may even be much older than that. It is difficult to know for sure, for as explained in previous newsletters the dating of most rock art still remains an uncertain science.

Fig. 1. This is an excellent example of an ancient palimpsest, eastern Changthang. Three animals created by thickly applying blood-red ochre onto a cave wall partially obscure older hunting scenes and other zoomorphic art.

The three more recently painted large red ochre animals appear to represent a yak, wild ass and raptor with outstretched wings. When writing about this composition in Divine Dyads (LTWA: 1997), I noted that this trio of animals holds an important place in the sacred geographic and clan traditions of the region. While the motivation for the creation of these pictographs and their intended function cannot be known to us with any certainty, the role of these animals in local culture (and that of Tibet more generally) inspired or may even have dictated their production. The rock art veiled is just as fascinating. The red ochre onager was placed upon a wild ungulate being chased by a bowman on foot, both of which are painted in yellow ochre. More of this hunting scene may be located underneath the yak. The hunter and his prey are part of the earliest tier of pictographs identified in Upper Tibet. They may date to the late Bronze Age (1200–600 BCE) or Iron Age (600–100 BCE) but this remains to be demonstrated utilizing the tools of science. As in other anthropomorphic renditions of early art, in this particular case the finely depicted anthropomorphic figure has two protuberances on its head, which may possibly represent horns or feathers (both of which are attested to in Tibetan literature pertaining to prehistoric culture and religion). The bow being fired is depicted by an arched line and the arrows as one or two straight lines. That this is indeed a bow and arrow is confirmed by the arm of the figure being pulled behind the body (as well as by a comparative study of other hunters in Upper Tibetan rock art). The wing of the red ochre bird is partially obscuring a wild ungulate (wild ass?) following a wild yak. These herbivores are also characteristic of the early phase of rock art at the site (slender strokes, angular lines, simple but bold outlines, a rich ochre palette, etc.).

The question remains: why did one artist decide to paint over the work of another artist? It may be that the later artist simply needed room for his painting conveniently supplied by using the same expanse of rock, the earlier art being ignored or devalued. Of course other motives may also be admissible, the truth about the provision of the painting under consideration forever elusive in any case. Perhaps the later artist wanted to add to the power of the local bestiary, acknowledging its sacred or economic status, a proud addition, not a denigration of the canvas of rock.

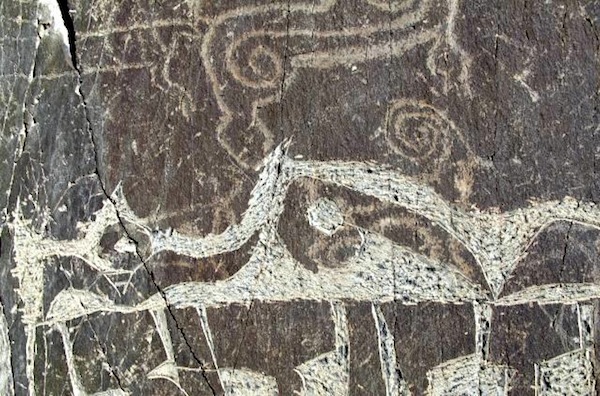

Fig. 2. The vowel sign of an Om syllable in the mani mantra partially engraved over the body of a stag, central Changthang.

Here we see the inscription grazing but not obliterating earlier artwork. That the mantra and stag date to very different time periods is clear by their physical condition. The stag is much more heavily re-patinated and it was made using a carving technique that left a much rougher surface. It may be that the stag was made using stone tools and the inscription engraved with metal tools, but this hypothesis requires rigorous testing and analysis and is tendered here only as a point of consideration. The vowel sign with its complex formation is indicative of a paleography used in rock inscriptions and moulded metal objects that I have documented extensively. This style of writing appears to predate the 13th century CE, as accompanying figurative art suggests. Some of these inscriptions may date as early as the imperial period (circa 630–850 CE). The deer belongs to a well developed genre of cervid art at this rock art site, all of which is of significant age. It can be dated to the Iron Age and protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE). I have written at length about the cultural historical features of deer in Upper Tibet (see my CV on this website for list of publications). Here it will suffice to say that this animal occupied a vivid position in the psyche of ancient inhabitants.

Why, then, did the carver of the mani mantra impinge upon the deer? Again, it may just be a matter of precious real estate, of an attractive and accessible rock face being subject to the imprint of successive generations, with some of the old having to make way for the new. However, ideological compulsions may also have been at play. We will scrutinize these motives below.

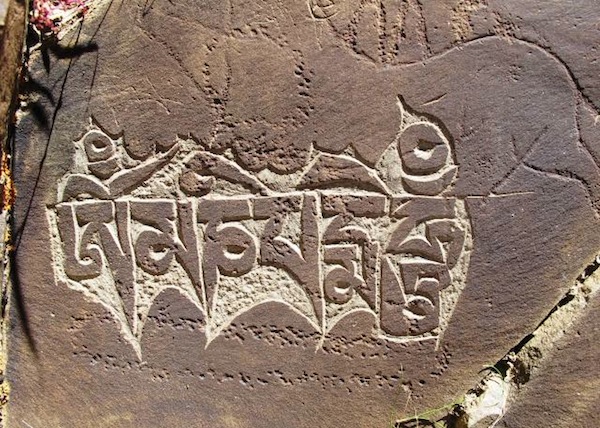

Fig. 3. A wild yak upon which the six-syllable mani mantra was carved, western Changthang.

The yak with its curved horns, humped withers and ball tail is unmistakable, these basic traits being reproduced in many hundreds of yak images throughout Upper Tibet. An attribution to the protohistoric period for the yak carving seems best indicated but an earlier date cannot be entirely ruled out. The mani mantra is of a much more recent origin, as its lack of erosion and re-patination shows. There are plenty of such minor rock panels at this site, thus a lack of suitable space for the mantra carving cannot be easily entertained. It rather appears that the maker deliberately stationed his mantra across the yak. The mani mantra is the single most popular prayer in Tibet, the sacred utterance for the bodhisattva of compassion, Chenresik (Spyan-ras-gzigs). This mantra expresses a deep regard for the welfare and happiness of all sentient beings. Perhaps therefore the inscriber wanted to express his or her sympathy for the ancient yak in the carving, many other examples of which form the prey of hunters, slaughtered with sharp-edged weapons for food and sport. Nevertheless, more calculating motives having to do with wresting ancient images away from older cultural beliefs and depositing them in the embrace of Buddhism can also be envisaged.

Fig. 4. A large rock panel crowded with older compositions upon which the mani mantra was written multiple times, western Changthang.

It appears that the engraving of the mantra was seen as bestowing religious merit on the carver, as is usually the case with the engraving of Buddhist syllables on stone, wood, paper, and on other mediums. The superimposition of mantras in this manner caused the defacement of much ancient art in Upper Tibet. This way of pronouncing the Buddhist faith is still being wrought on the region’s rock art and should be guarded against by conservators in the interests of protecting the ancient cultural legacy of uppermost Tibet.

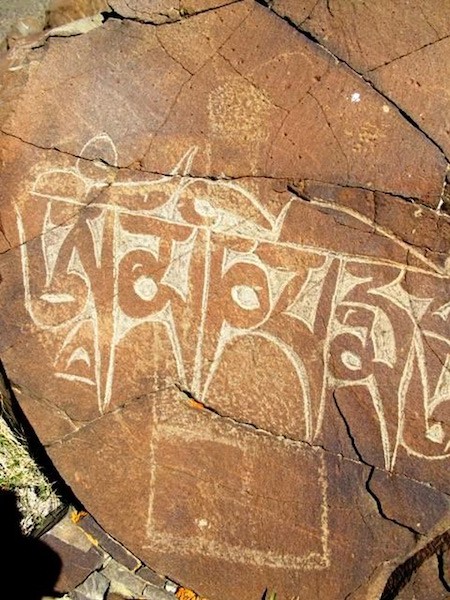

Fig. 5. The mani mantra carved over a complex scene consisting of horsemen, wild ungulates and other figures, western Changthang.

The mantra maker obliterated most of the earlier composition. We might infer from this that he or she saw the ancient demonstration of hunting as something needing serious amendment or reconfiguration. Perhaps a deep compassion for the slain animals is evinced by this action. Yet, other motivations seem to speak through this effacement of ancient art as well. I think that the mantra maker wanted to recreate or revise the ancient rock art by placing the stamp of Buddhism upon it, subjugating or voiding the cultural values incumbent in an unabashed show of communal hunting. The killing of animals, especially when it is so brazen, is of course an anathema to Buddhists.

Fig. 6. The mani mantra partially inscribed on what looks like a carnivore (tiger?). The respective physical condition of the carvings indicates that a great many centuries separate the zoomorphic subject from the Buddhist engraving.

Fig. 7. Two ancient yaks with the strokes of a giant mani mantra cut over them. Other ancient art was also obliterated by the mantra, western Changthang.

Not only did the mantra maker have little regard for the earlier carvings (on the grounds of style and physical condition, the two wild yaks appear to date to different remote periods), his activity must have been seen as meritorious to fellow religionists. Buddhist polemical literature about the darkness and evil of pre-Buddhist times in Tibet encourages such a view. Moreover, in the popular imagination, ancient culture (commonly called bon) is still often looked upon as something undesirable. Viewed in this manner, the engraving of the mantra becomes an act of vandalism.

Fig. 8. Wild ungulates including a yak being attacked in the rear by a striped carnivore (tiger?), whose execution was inspired by the animal style of the steppes. These compositions are partly concealed by the mani mantra, northwestern Tibet. This animal art dates either to the Iron Age or protohistoric period; the mani inscription of course being added much later.

Fig. 9. Probable wild yak hemmed in by Tibetan letters, western Changthang. This is another egregious example of the ancient being infringed upon by the more modern, probably carried out for ideological reasons.

Fig. 10. Much of this ancient yak petroglyph was spared by the mani mantra maker, a good thing in terms of preserving ancient cultural materials. The wild yak is of the Iron Age or protohistoric period, and the mantra is from the last few centuries and may be quite recent.

Fig. 11. A so-called mascoid, a relatively rare and historically valuable subject found in various configurations throughout Inner Asia. It was damaged by a deeply incised mani inscription, the carver adding it on religious grounds for good measure. This muffin-shaped mascoid is ornamented with circles in its lower half but the design of the upper half is no longer discernable. The mascoid may be of the late Bronze Age or Iron Age, northwestern Tibet.

Fig. 12. Two wild yaks, northwestern Tibet. One of them was partly shrouded by the spire of a chorten. Another wild yak of much antiquity was corralled in the bottom right-hand portion of the chorten.

The chorten appears to date to the early historic period, as the style of its various components indicates (small bumpa, prominent harmika, serrated spire, etc.). It is possible that this is a rendition of a bon rather than a Buddhist monument. If so, it demonstrates that the alternative religious tradition also imposed their motifs upon earlier art. Nevertheless, there are very few examples of patently Yungdrung (Lamaist) Bon mantras overlying prehistoric rock art. The respective historical perspectives of the two great Tibetan religious traditions may account for their differing treatment of ancient rock art. Simply put, Yungdrung Bon highly values indigenous origins and traditions, Buddhism less so.

Fig. 13. In this image there is rock art of three different periods represented by the equid (?), tiered shrine and mani mantra, northwestern Tibet.

The bottom part of the possible horse or wild ass was consumed by the stepped shrine (perhaps of the gsas-mkhar or lha-rten class, which is used to enshrine deities). This shrine with its small round bumpa crowning a graduated base was pecked into the rock surface, while the equid was carved with deep, steady lines. The ostensible equid exhibits more re-patination than the shrine and thus appears to be older (microenviromental forces do not seem to account for differences in their physical status). This shrine almost certainly was made by those following archaic (bon) religious traditions probably in the protohistoric period, an example of the creation of palimpsests by predecessors of the Buddhists. Time of course does not stand still and as a final creative act a mani mantra was squarely carved over the shrine. This was no accident and to my mind symbolizes the Buddhist usurpation of the vestiges of past religious legitimacy.

Fig. 14. The basal rock art consists of an archaic chorten with three tall tiers, small round bumpa and horn-like finial, northwestern Tibet. At a much later date the mani mantra was added smack over the middle of the chorten. This suggests that the chorten was made by those who followed archaic religious traditions, the mantra added as a kind of ritualized subjugation. This action needless to say bespeaks a certain zealotry.

Fig. 15. Two archaic red ochre shrines or chortens are visible in this image, eastern Changthang. Superscriptions of the mani mantra were scrawled on top of the shrine on the left, while the seven-syllable mani mantra (with the addition of hri) and Om’ A’ hum’ were carved on the specimen on the right. In a visual sense, this singling out of ancient religious symbols for branding with Buddhist mantras conveys a stridency.

Fig. 16. A red ochre endless knot (dpal-be’u) defaced by a carving the seven-syllable mani mantra. Here, too, the presence of the mantra suggests that this auspicious symbol belonged to the adherents of archaic religious traditions, the addition of the mantra a kind of purging of the past.

The Upper Tibetan Buddhists of the last millennium could hardly match the archaic epoch in terms of the scope of its religious infrastructure, agricultural potential, military might, and possibly population size as well. This is clearly indicated by the archaeological record. Perhaps, then, as part of the ongoing Buddhist conversion of the region, more subtle or symbolic means of degrading or neutralizing the earlier cultural legacy assumed special significance, the gesture sufficing where more robust physical demonstrations of superiority were not feasible. It is in this light that the superimposition of Buddhist mantras on ancient rock art might be best understood.