November 2011

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome on another Flight of the Khyung! This month and in the months to follow this newsletter shall highlight discoveries made on the Upper Tibet Rock Art Expedition II (UTRAE II). I am pleased to report that this recent mission was an unmitigated success. Twenty-four different rock art sites were surveyed, four of which were documented for the first time. Among the 24 rock sites visited this year were five that were surveyed earlier by Sonam Wangdu and Li Yongxian. This was my first opportunity to visit these rock art theatres. Most of the other 15 sites were documented by me in the 1990s and 2000s. Revisiting them was to very good effect, because hundreds of new compositions came to light including those of considerable importance. Working intensively for more than five weeks, I managed to shoot more than 11,000 photographs, the most taken on a single expedition.

Probably the single biggest discovery this year was pinpointing the epicenter of mascoid rock art in Upper Tibet. The so-called mascoids are highly symbolic anthropomorphic compositions, each of which is unique in style. The astounding array of mascoids in Upper Tibet is directly comparable to those of Ladakh, Indus Kohistan and northern Inner Asia. This discovery establishes an uninterrupted pathway of communications from Transbaikalia to Tibet, cultural intercourse that gave rise to an analogous genre of rock art. Along with other archaeological evidence linking Upper Tibet to the steppes, mascoids demonstrate that this region was once part of the Eurasian pan-cultural orbit. This is liable to have weighty ethnohistorical implications, the nature of we are only beginning to fathom. Mascoids are commonly thought by rock art specialists to date to the Bronze Age. In any case, this intriguing Tibetan art form is very ancient, even if some of it dates to the early Iron Age, which I suspect may be the case. There will be more on Upper Tibet’s mascoids in next month’s issue.

In addition to rock art, two archaic fortresses were documented on the UTRAE II, including one of very significant size and importance. All shall be revealed in the issues to follow!

Revisiting the chariots of Upper Tibet

Let us begin where we began last year when describing the findings of the UTRAE I (August, 2010). On the UTRAE II, what appear to be chariots were found in the central Changthang and in northwestern Tibet. The discovery of the likeness of a wheeled vehicle in northwestern Tibet is the first of its kind. It geographically links the rock art chariot discovered in Ladakh with those of the Changthang. It was puzzling to me that chariot rock art had not been found in northwestern Tibet because this appears to have been a major conduit between the wider Tibetan Plateau and north Inner Asia. So, one of my big hopes for the UTRAE II was that one would show up. Happily one did, but being depicted without draught animals renders its identification less than absolutely certain.

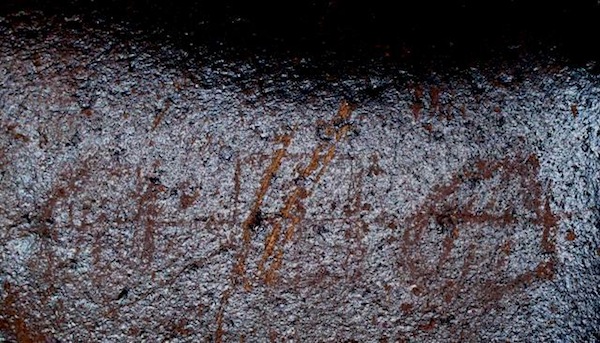

Fig. 1. Chariot sans draught animals found this year in northwestern Tibet. The box, wheels and central beam are all clearly depicted on this somewhat stylized version of the chariot. On adjacent panels is animal rock art of the same age and in typical Upper Tibetan style.

Rock art chariots of the central Changthang were first discovered by Lobsang Tashi, a rock art researcher at Tibet University (see August, 2010 newsletter). One of the two specimens he found was located quite far north in the Changthang. This year, I came across a second chariot in the same proximity. Again, it is depicted without the horses that would have pulled a real-life version (however, the one studied by Lobsang Tashi in the same area appears to be shown with horses). Every rock art chariot that comes to the fore strengthens Upper Tibet’s association with this vital technological and strategic innovation. The chariot, as much as any other archaeological discovery, establishes Upper Tibet’s Eurasian credentials. It also raises all kinds of questions. Chief among these is what agent(s) led to its introduction in Upper Tibet? Did Bronze Age invaders from the steppes actually ride onto the Tibetan Plateau in a spectacular show of military prowess? While we cannot rule out military incursions, the reasons for the Tibetan adoption of the chariot are probably a good deal more intricate if even a little less dramatic. Trade, cultural sharing, technological exchange and political alliances / rivalries are likely to be part of the equation. These interactions may or may not have been accompanied by the mass movements of people. We must await further genomic research concerning the genetic makeup of the Tibetan people before ascertaining the impact of any demic diffusion. Other big questions are when did Tibetans first learn about chariots and when did they begin to make facsimiles on rock?

Fig. 2. The chariot of the central Changthang documented on the UTRAE II. This specimen is also bereft of its draught animals. While the wheels and axle are clearly portrayed, rather than radiating from the hub, the spokes are vertically arrayed. Like most other Upper Tibetan rock art chariots, this one has a square car.

Fig. 3. The chariot of the central Changthang was carved on the saddle-shaped boulder in the foreground. The carving is located on the side of this rock facing the large lake basin. This is a curious location, not typical of the rock art site in general but one that may have had a deliberate purpose. Perhaps actual chariots once raced across this basin. It is certainly level and unobstructed enough to have hosted wheeled vehicles. If so, this petroglyphic chariot may have heralded their arrival in an act of tribute, remembrance or ritual celebration.

The systematic destruction of Guge’s ancient chortens

It was only this year that I have come to fathom the degree of looting that has taken place in Guge, one of Upper Tibet’s premier cultural regions. Looting in recent years has been widespread and highly systematic, the result of a collaborative effort that seems to reach far and wide. Earlier, according to information received, I thought this looting was carried out by isolated criminal gangs. However, this is only part of the picture, or so it seems.

It is reported that many sites with ancient chortens (stupas) have been ransacked in the last three to five years. These chortens were opened to recover marketable goods. From what I hear, among the most valuable artifacts found were religious paintings on cloth known as thangkas.

Fig. 4. The recently vandalized chorten complex of Darkam. At this remote site the looters could work at leisure. They opened every single chorten, cleaning out with meticulous care every single repository.

Fig. 5. A close-up of a Darkam chorten. The thieves left not one stone unturned in their search for saleable objects. The disgorged contents and structural elements lie below the chorten.

The 11th and 12th centuries were a time of great chorten building in Guge as part of the second diffusion of Buddhism. Guge was of course a great center of Buddhist learning and monastic development in that period. A significant portion of the chortens destroyed in recent years appears to date to the 11th and 12th centuries CE. As noted in Flight of the Khyung last year, while the finials and spires of chortens were destroyed in the Chinese Cultural Revolution, the central bulbous portion (bumpa) of these structures was often left intact. It is inside the bumpa that sacred objects were enshrined as part of the consecration process. It is through the consecration process that the beneficial properties of chortens are believed to be activated. Tibetans see chortens as a means of propagating the Dharma, protecting the environment and preventing natural disasters. Blessed earth, medicines and cloth, and jewels as well as holy images are often deposited inside as part of the empowering of a chorten. Damaged sacred objects like broken statues or water-damaged scriptures were also customarily placed in chortens, as a way of dealing with things that were no longer functional but which could not be cast away like ordinary refuse.

Their cultural and historical value aside, whatever spiritual aid the ancient chortens may have provided Guge is now consigned to history. Dozens of sites consisting of hundreds of chortens have been despoiled. There is however one valley where the thieves were not successful. This success story is all down to a savvy headman and his alert villagers. Thanks to their vigilance the chortens of the famous Dungkar valley were largely spared. To be sure, thieves visited Dungkar, as they did almost every other valley in Guge, but they were caught in the act and detained by the villagers. These five miscreants from eastern Tibet were turned over to the police and given long prison sentences. When caught they were in possession of a thangka they had looted from one of the Dungkar chortens. The looters however have their masters and these people are still at large, embedded as they are in the society.

Fig. 6. The chorten complex at Hala, another remote site in Guge. Three or four years ago every chorten at this location was violated.

Fig. 7. In this close-up image the central axis (srog-shing) of the chorten is visible. This timber and others like it can potentially tell us much about environmental conditions in olden Guge. In Hala, the thieves with almost surgical precision emptied every chamber of every chorten of its contents.

Fig. 8. The recently ransacked chorten complex of Khyunglung Yulme. These chortens are situated near a large village but despite their conspicuous location they were not safe from the well supported activities of thieves. This site and the caves above are now being developed for mass tourism with the construction of a road right up to its base. The lovely white pools of a nearby sacred hot spring have been run over by a bulldozer for no apparent reason.

Now that most of the chortens of Guge are mere shells, it might be useful for the Cultural Relics Bureau or some other concerned organization in the PRC to scientifically date some of their wooden members, in a bid to better understand the history of these monuments. It is also high time for the authorities to devise an effective plan for the conservation of Tibet’s ancient architectural heritage.

Fig. 9. A largely intact circa 11th century CE chorten at Manam Gonpa, Guge.

More on the golden funerary masks of the Himalaya

Fig. 10. The golden burial mask of Gu-ge. Photo, courtesy of Li Linhui

In last month’s newsletter, I introduced readers to three golden funerary masks recently discovered in tombs in Guge, Uttaranchal and Mustang. To better comprehend the significance of this archaeological material it is useful to place it within a broader geographic and cultural context. In the Old World, the use of golden funerary masks can be traced to Egypt and Mycenae, circa 1500 BCE. There are also gold burial masks from the West that date to the Iron Age, the period in which we might expect the first Himalayan specimens were made. For example, a Thracian golden funerary mask was discovered in Bulgaria’s ‘Valley of the Kings’. Dated to circa the 5th century BCE, the figure on this mask is heavily bearded and thought to be of royal rank. Golden death masks of Greeks from this same timeframe have been unearthed in the Republic of Macedonia, on the island of Samos and in the Bosporus.

Closer to our area of interest is the gold death mask of the so-called Yingpan Man of the Tarim Basin. It is made of two pieces of gold foil joined through rivets and solder. The face is decorated with inlaid rubies. This burial mask is thought to date to circa 3rd of 4th century CE. Its facial features are not unlike those of the Sam Dzong mask of Mustang, perhaps another indication of the interconnections between these two regions that other archaeologists are exploring. The Guge funerary mask is also a great work of art and comprised of two plates of solid gold or gold leaf on a metal base (we must wait for the report from Li Linhui et al. to know which). However, its facial features and construction are very different from the Tarim Basin specimen. As much as these masks represent the actual visage of the deceased person they accompanied, we can see the differing physiognomy as reflecting distinctive ethnic and / or cultural sources. Like the rock art mascoids of Upper Tibet, each of the three golden masks of the Himalaya is unique. This individuality is in accord with the ‘golden face’ (gser-gzhal) of the Tibetan archaic funerary tradition: the likeness of the deceased reproduced as part of the evocation rite of the soul or consciousness principle.

The Guge funerary mask is also distinctive for its embossed wild ungulates and birds. The archaic religious and secular traditions of Tibet, as recorded in Old Tibetan and Eternal Bon literature, are replete with zoomorphic imagery. Animals assume myriad functions as part of a mythic and intellectual universe where they were viewed as spiritual, ancestral and ecological figures responsible for human well being. The Guge mask mirrors this overarching cultural theme; of animals as the allies and guides of the dead. To better understand the burial masks of the Himalaya, a comprehensive comparative study is needed. Of special interest to such a study are the burial masks of Siberia (late first millennium BCE to circa the 7th century CE).

In Inner Asia golden burial masks continued to be made as late as the 11th century CE. A Khitan burial mask from 1018 CE was found on the corpse of Xiao Shaoju, the husband of the fabled Princess Chen. The custom of making such masks was part of various non-Buddhist funerary rites. In Tibet these old rites fell out of favor after the 9th century CE. The diffusion of golden burial masks in ancient Eurasia is but one funerary tradition that spread widely throughout the region. The challenge before us now is to trace these cognate traditions through time and space. This is a formidable task requiring the expertise and energy of scholars from various disciplines.