May 2016

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to Flight of the Khyung as we ascend to the highest of heights! In this month’s issue there is an article on the recent discovery of six rock art sites in Ladakh by anthropologist, explorer and rock art researcher Viraf Mehta. This rich assortment of ancient carvings is located near the frontier with China and Pakistan, an area still closed to tourists.

The second feature in this newsletter is by its principal author, John Vincent Bellezza. It is the first in a two-part article on the swastika in the rock art of Upper Tibet. This work is dedicated to the memory of an individual of uncommon compassion, insight and strength, one who passed away peacefully in the gathering light of a new day.

The Final Frontier: The rock art of the upper Nubra valley, Ladakh

Text and photographs by Viraf Mehta

Over the past seven years (2009 to the present) I have travelled on my own and with colleagues and friends to almost all corners of Ladakh and in all seasons to document and help protect its rapidly vanishing rock art.

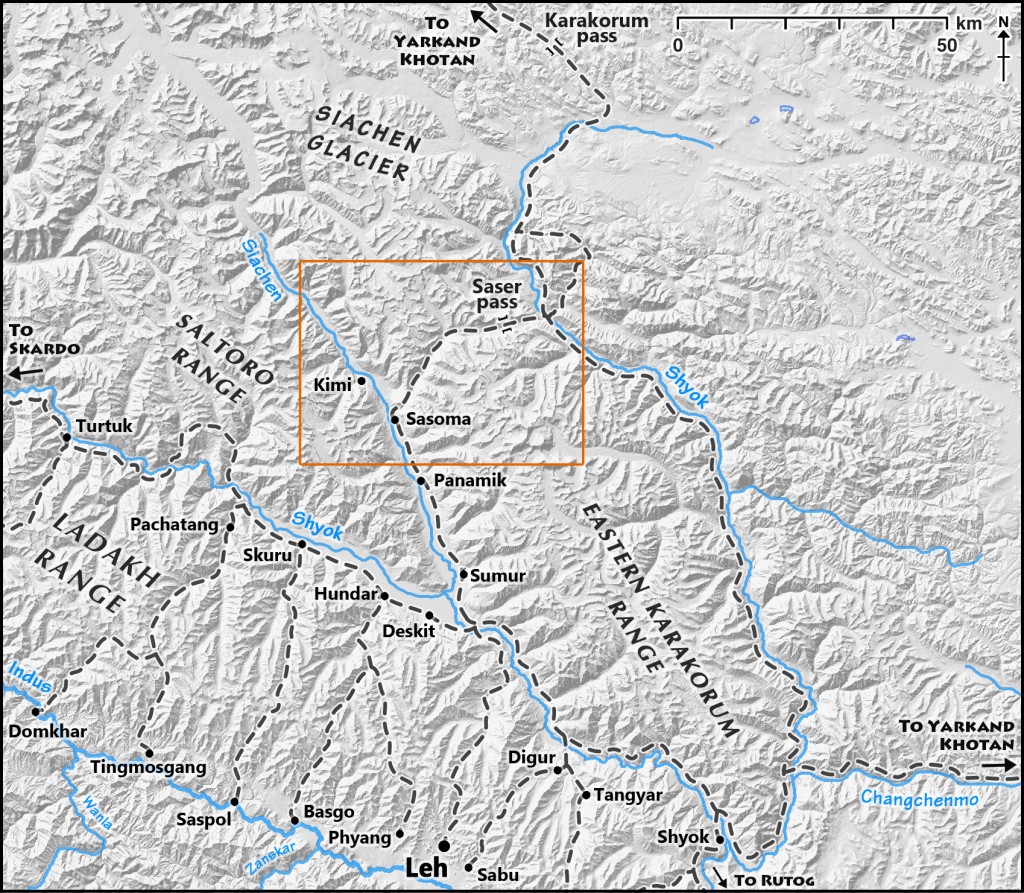

This article focuses on previously unpublished petroglyphic sites I found north of Panamik, along the Nubra or Siachen River and on the Saser La route. The Nubra (L’Dumra) valley lies north of the Ladakh Range. It has contested borders with Pakistan (Baltistan) and China (western Tibet).

The Nubra valley is drained by the Nubra or Siachen River, a major tributary of the Shayok River and an extension of the infamous Siachen glacier, the world’s longest mid-latitude glacier and highest battlefield.

The Nubra valley is amongst the richest repository of Ladakh’s ancient archaeological and rock art (petroglyphs) heritage, which reflects ancient trade and religious routes that passed through it, particularly those that went across the Saser La and Karakoram Pass, en route to Yarkand. There are approximately 25 known rock art sites in the Nubra area, with the majority of them along the Nubra River and in proximity to its confluence with the Shayok River.

Although the geopolitics of the region continue to keep key areas of the Nubra valley out of bounds for domestic and foreign tourists, the Turtuk area bordering Pakistan, was opened to tourism in 2010.

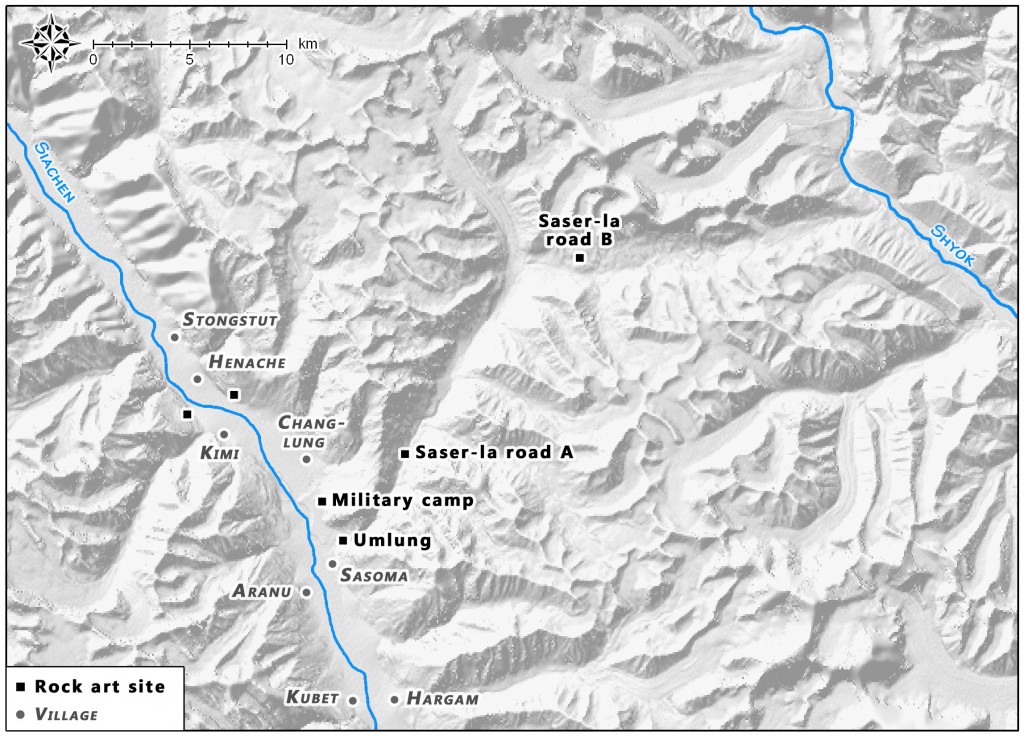

Fig. 1. Map of the Nubra valley and surrounding areas. Note that modern political boundaries are not designated on this map. Map by Quentin Devers.

The sites covered in this article are as follows:

- Khimi: a village on the right bank of the Nubra River.

- Sasoma: comprised of two sites, which includes one in proximity to an Indian Military Camp (10 km south of Khimi) and one at Sasoma Umalung.

- Henache: consists of two sites, the northernmost rock art documented in Ladakh.

- The road to Saser La: comprised of two separate sites.

1) Rock art at Khimi is found on random large boulders as well as on the rocky slopes of hills.

Fig. 4. An unusual example of an ancient artist using a ridge on a rock surface to highlight the ascent of ibex, which are shown reduced successively in size, Khimi. Other animals are also depicted on the boulder.

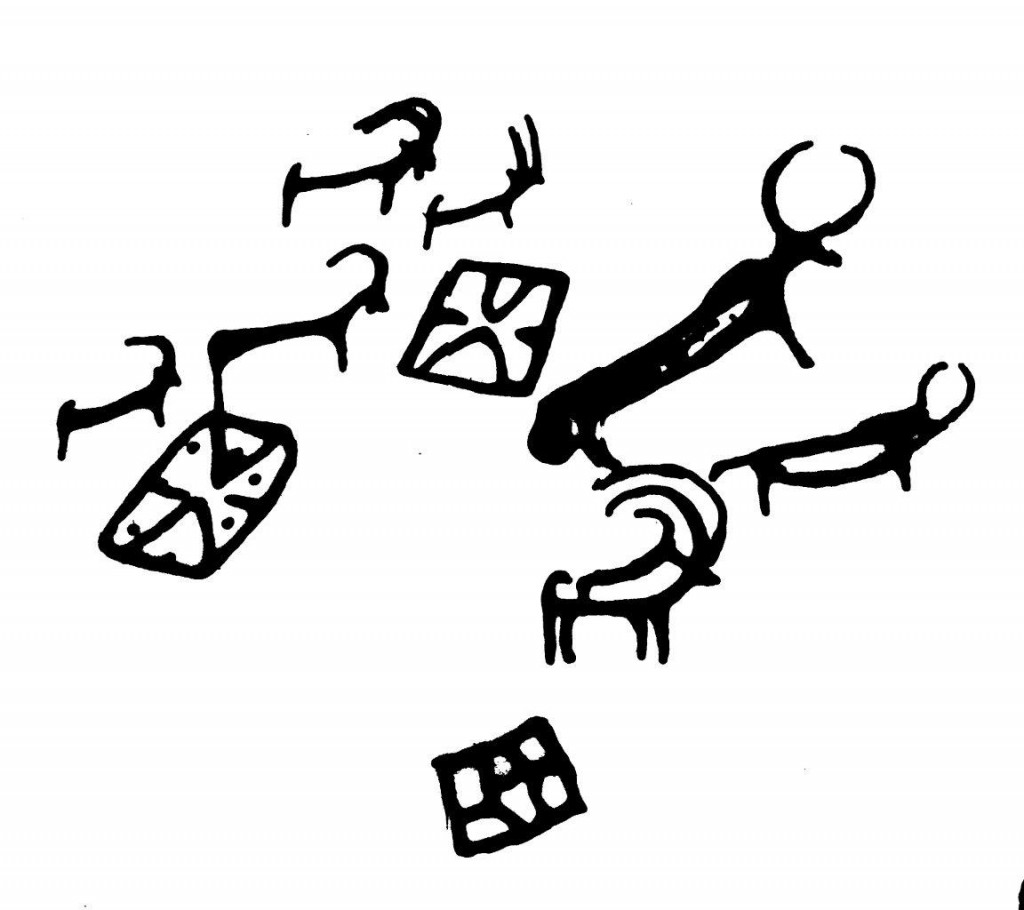

Fig. 6. A scene of horsemen on mounts with elongated legs/tails and other animals, Khimi. Nearby panels depict sheep and ibex. Drawing by Tashi Ldawa.

Fig. 7. A large 2-m long rock slab at Khimi, where an anthropomorphic form is seen with arms outstretched (the right arm is more clearly visible) and surrounded by various animals, including wild sheep, etc.

2) Sasoma is a village about 15 km north of the village of Panamik (the point up to which tourists are currently permitted to visit), and also the site of a military camp that regulates entry to the Siachen Glacier (Siachen Base camp is 45 km from Sasoma).

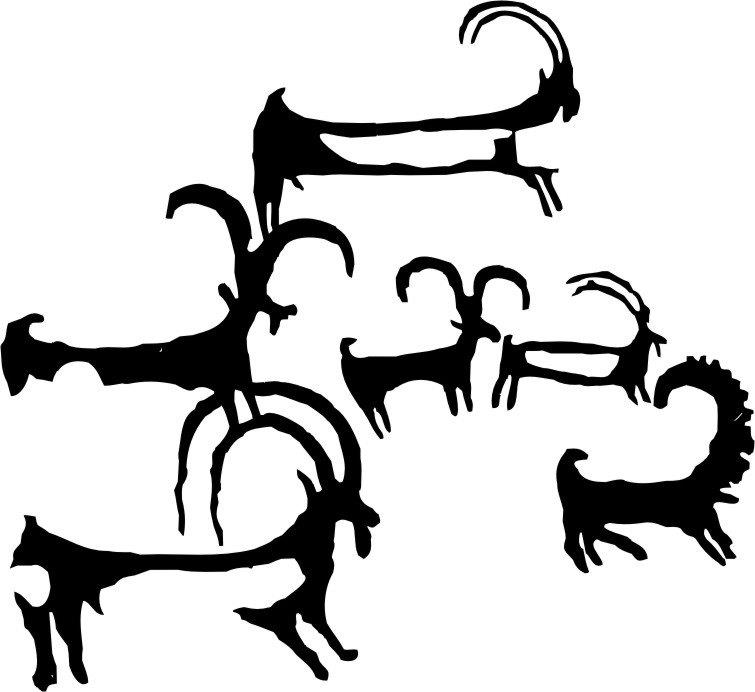

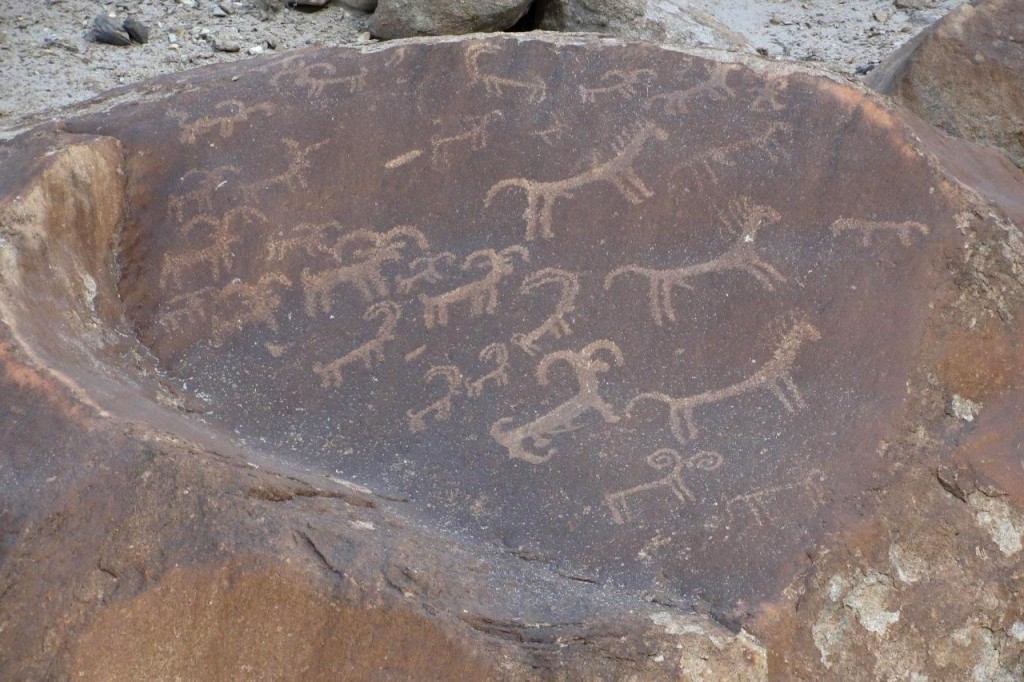

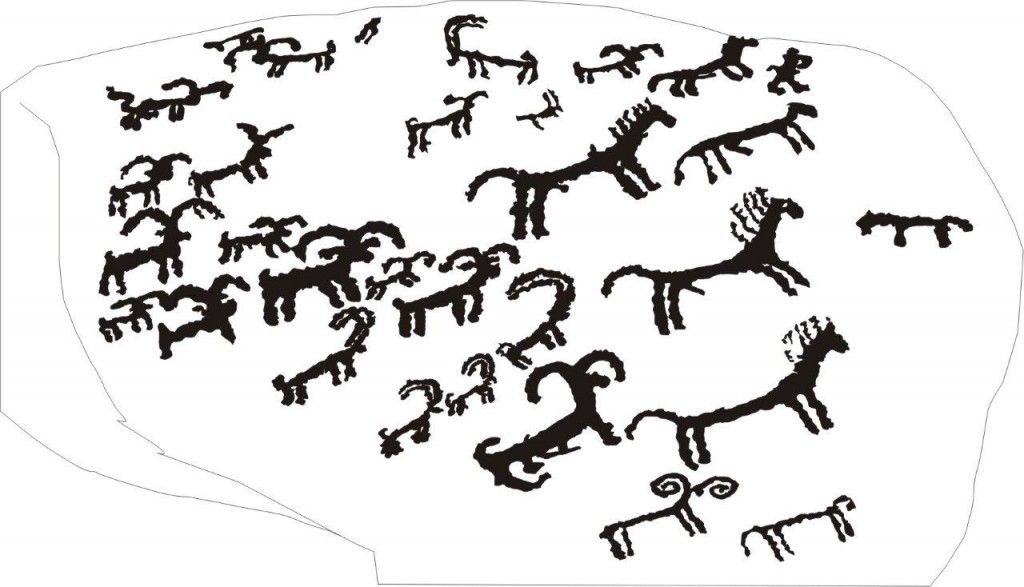

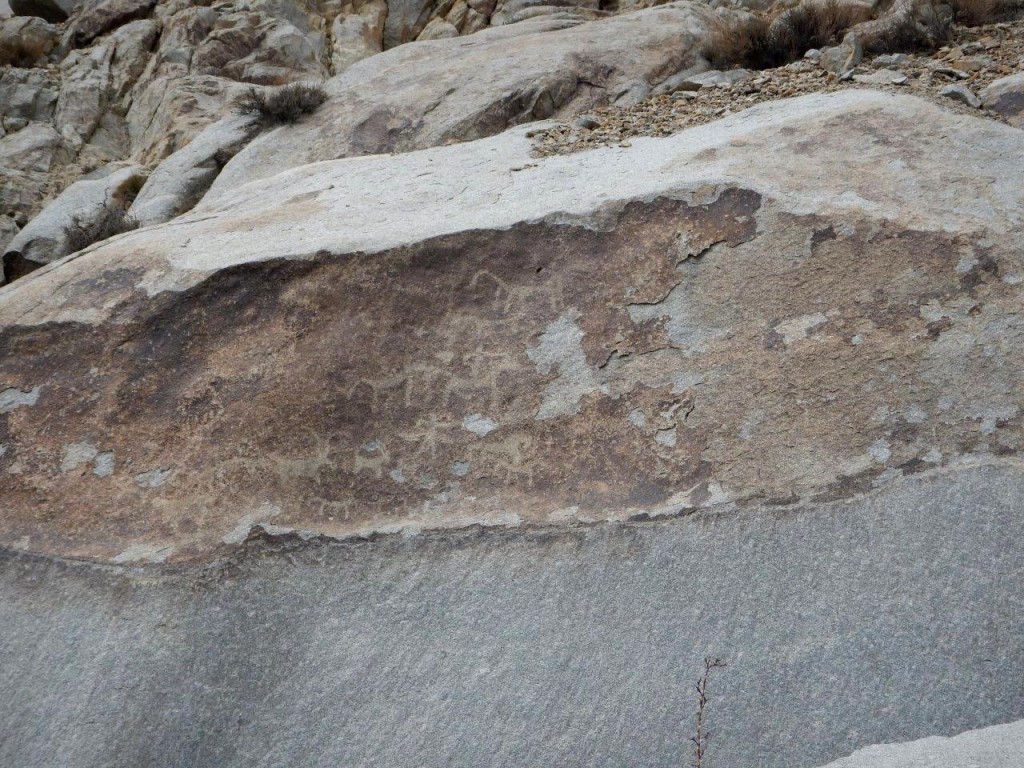

Sasoma-Umlung is a wide, flat camping ground just below a large rocky hill across which a dangerous zig-zag road traverses. There are thirty to forty boulders with petroglyphs of animals, hunting scenes and horsemen at this site. At Sasoma Umlung there are ibexes and wild sheep rendered in differing styles and accompanied by geometric shapes.

3) The village of Henache is located about 15 km north of Sasoma. The remaining petroglyphs spared from destruction by the construction of the Siachen road depict animals and horsemen on weathered rock.

4) There are two sites thus far identified along the 52 km road to the Saser La (approximately 5400 m elevation). The road begins at Sasoma and eventually meets up with the old trade route along the Umlung nala/chu. The lower rock art site is about 19 km from the start of the road and was probably an ancient encampment. Most of the petroglyphs here depict animals and hunting scenes. They are heavily re-patinated and engraved/etched on boulders and other rocky outcrops and shelters.

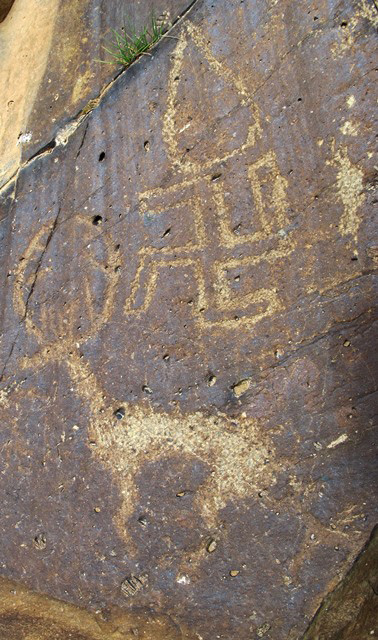

Fig. 21. A single boulder with anthropomorphs in a dancing/celebratory scene, accompanied by animals and horsemen, lower site, Saser La. A faint chorten outline is visible in the centre of the boulder.

The upper Saser La road site (4300 m) is situated on a rock strewn/grassy slope and consists of just two boulders with petroglyphs. It is located about 20 km ahead of the first site.

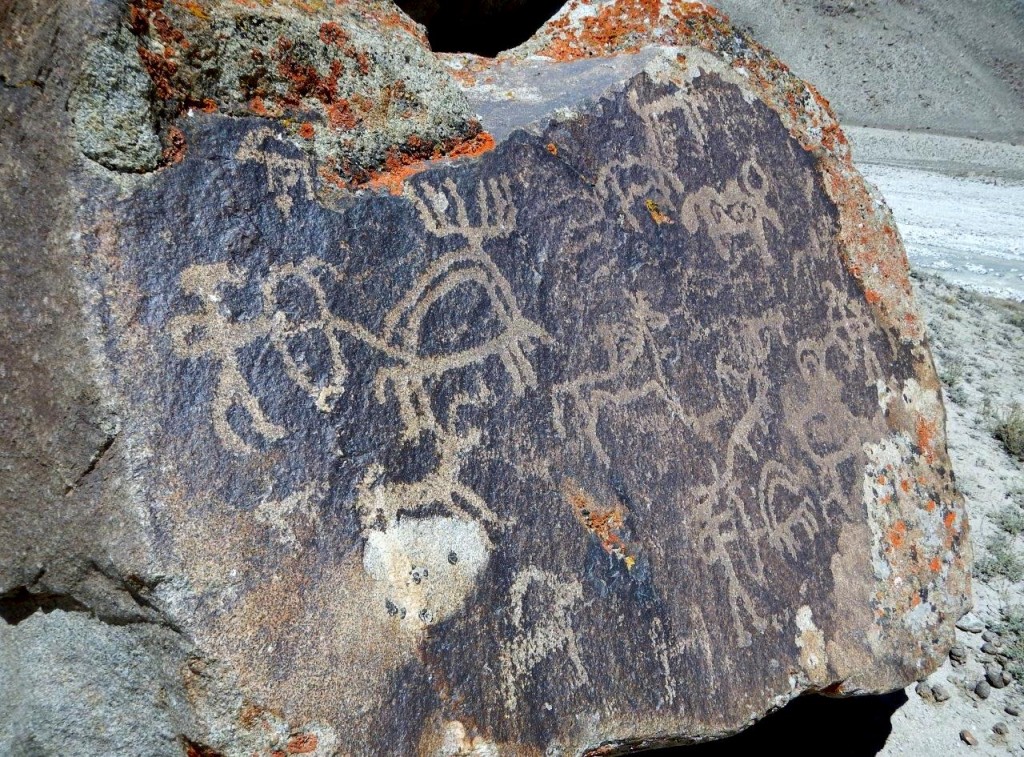

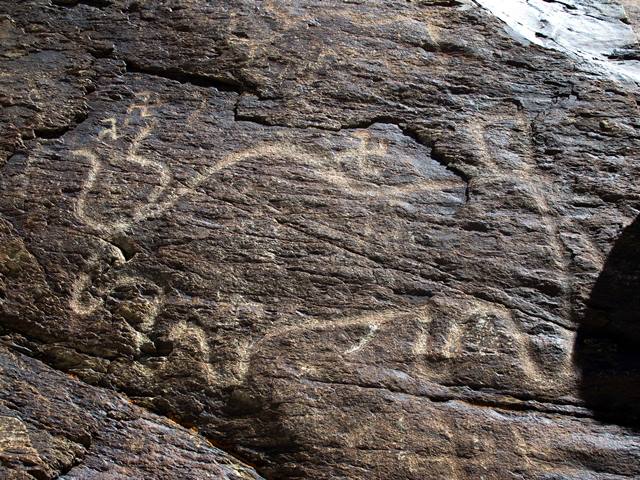

Fig. 23. Hunting scenes with bowmen, yak, horse, sheep, and possibly a carnivore are clearly visible, despite a lot of surface wear on the rock. Note the S-shaped interior design of the yak.

Editor’s Comments

Recent discoveries by Viraf Mehta in the upper Nubra valley add six new rock sites to the more than 180 already documented in Ladakh. His reconnaissance work is very welcome and hopefully it will lead to a thorough survey of these six sites. The rock art Mehta has documented complements earlier discoveries in Nubra and other regions of Ladakh, enhancing our understanding of formative artistic and cultural influences emanating from north Inner Asia, as well as adding to our picture of the indigenous complexion of the region in antiquity.

The anthropomorphic figures with large hands gesturing upwards from Khimi and Sasoma, the array of mascoids (anthropomorphic visages in emblematic form) from the Sasoma Military Camp, and the elongated forms of many wild herbivores chart the injection of north Inner Asian esthetics and semantics of the Bronze Age into the Nubra valley. On the other hand, the wild yak with S-shaped body ornamentation in fig. 23 chronicles Eurasian animal style inputs from the Iron Age. These cultural interconnections with the north are readily understandable, as the Nubra valley is geographically linked to the Tarim Basin, a Bronze Age and Iron Age demographic and cultural entrepôt.*

For more on north Inner Asian influences in the rock art of Ladakh, see, for example:

Bruneau, Laurianne. 2010. “Le Ladakh (état de Jammu et Cachemire, Inde) de l’Âge du Bronze à l’introduction du Bouddhisme: Une étude de l’art rupestre, vols. 1–3. Ph.D. dissertation, Université Paris I-Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Bruneau, Laurianne and Bellezza, John V. 2013. “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’”, in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28, pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS. http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf

Bruneau, Laurianne. and Vernier, Martin. 2010. “Animal style of the steppes in Ladakh: A presentation of newly discovered petroglyphs”, in Pictures in Transformation: Rock art Researches between Central Asia and the Subcontinent (L. M. Olivieri et al.), pp. 27–36. Oxford: BAR International Series 2167. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Francfort, Henri-Paul / Klodzinski, Daniel / Mascle, George. 1992. “Archaic Petroglyphs of Ladakh and Zanskar”, in Rock Art in the Old World: papers presented in Symposium A of the AURA Congress, Darwin (Australia), 1988 (ed. M. Lorblanchet), pp. 147–192. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts.

The rock art recently found by Viraf Mehta in the upper Nubra valley also expands the scope of hunting scenes, zoomorphic portraiture, and styles of depiction that help define a distinctive rock art realm in Ladakh. This shared sphere of artistic, mythological, ideological, cultic traits (also common economic and environmental factors) has well delineated geographic characteristics. Taken as a whole, endogenous links set apart the tradition of rock art in Ladakh from surrounding territories of northern Pakistan, the Tarim Basin, Spiti, and Upper Tibet. Although there are many shared patterns of conception and depiction in their rock art repertoires, these did not deter the development of integral cultural and artistic systems in Ladakh. This integration also served as a counterpoint to considerable areal variability in native rock art forms in Ladakh.

A Mirror of Cultural History on the Roof of the World: The swastika in the rock art of Upper Tibet – Part 1

Introduction

This article relates the tale of the swastika in Upper Tibet. It begins deep in prehistory on the highest reaches of the Tibetan Plateau and continues to the present day with the Bon and Buddhist religions. The highly storied swastika could be the central theme of an entire book about the cultural history of Tibet. Here, however, only a sketch of this seminal symbol is possible, highlighting its place in the cultural life of Tibet over the last three millennia.

The swastika is well represented among at least 10,000 rock carvings and paintings documented in the vast Upper Tibetan territory (Stod and Byang thang). In fact, it is the most common symbol in this rock art. It is also the most versatile, appearing in many different kinds of compositions. Over the course of the last two decades, I have documented close to 300 swastikas in Upper Tibet carved and painted on boulders, cliffs, ancient ruins, and in caves. This curious sign occurs at approximately 70% of the more than seventy rock art sites discovered in the region.

The swastika, also known as the fylfot, gammadion, tetraskelion or hooked cross, is an equilateral cross terminating in four legs oriented perpendicular to the two axes and at right angles to one another. This archetypal form elegantly embodies both linear and radial geometries, a compelling factor in its longstanding allure.

The English word swastika (and that of many other European, Indian and Central Asian languages) is taken from the Sanskrit svastika, meaning ‘mark of well-being’. Generally speaking, the swastika is a manifestation or emblem of good luck, auspiciousness, prosperity, well-being, stability, the sun, and sundry religious doctrines and esoterica. The swastika is known in many traditional cultures worldwide, a sacred symbol originating in the Stone Age. It has appeared on a large variety of textiles, basketry, stone and metal sculptures, and a host of other decorative, ritual, martial, and utilitarian objects.

The swastika occupies a prominent position in Jainism and Hinduism, and it has been an important Buddhist symbol since the early days of this religion. In Buddhism, the swastika epitomizes the profound nature of the Buddha and his inviolable doctrines. Tibetan Buddhism has inherited the symbolism of the swastika from India, adding to it an indigenous layer of mystic meaning and symbolism.

The Tibetan word for swastika, yungdrung (g.yung drung) is not derived from the Sanskrit (nor are words for the swastika in Mongolian, Chinese, Albanian, etc.). This term has a Bodic linguistic lineage. Among the earliest recorded uses of yungdrung occur in manuscripts and pillar inscriptions of Tibet’s Imperial period (circa 650–850 CE). There are several examples of the word yungdrung appearing in the pillar edicts and chronicles of the Tibetan kings, where it signifies stability and eternity. For early Buddhist missionaries in Tibet, the swastika was synonymous with essential religious matters, becoming a stamp of Buddhist teachings, a synonym for nirvana, and a lexical term for “eternal”. This is an excellent example of how indigenous terminology was exploited to convey the new religious doctrines being introduced to Tibet from India.

As important as the swastika is to Buddhism, it has an even more vital role in the other major religion of Tibet: Bon. The swastika is the main epithet for that religion, which has called itself Yungdrung or the ‘Eternal’ Bon for a thousand years. According to the Bon tradition, g.yung drung means ‘unborn, undying’, and is synonymous with eternity, immutability and imperishability. In the extinct Zhang Zhung language of western Tibet, the word for swastika is drung mu, which is etymologically related to its Tibetan equivalent.

A brief survey of the swastika in the cultural and religious traditions of Tibet

In the Yungdrung Bon religion, the counterclockwise swastika is a sign par excellence of the enlightened mind (g.yung drung sku; equivalent of the Buddhist chos sku), which is primordial, intrinsically pure, all-knowing, all-compassionate, empty of compounded phenomena, and possessing many other supernal qualities. Numerous Bonpo are named Yungdrung, as are many fabled sites and temples in their history. Some Bon deities have the appellation Yungdrung or display the swastika as an attribute or ornament. The religious heroes or bodhisattvas of Bon are called the ‘impeccable beings of the swastika’ (g.yung drung sems dpa’). Moreover, the power of Bon is symbolized in a scepter (chag shing) displaying a counterclockwise swastika on both ends.

In Yungdrung Bon, the ‘swastika consummation path’ (g.yung drung grub-lam) leads to liberation, the ultimate state of existence characterized by bliss and pure awareness. In Bon funerals the positions or stages on the path to liberation are symbolically marked by swastikas drawn on a long white cloth, through which priests (’dur gshen) guide the deceased. An older variant of this tradition imbues the swastika with a less metaphorical identity. The last of nine levels leading from the underworld to the ancestral realm or heaven is referred to as ‘undying swastika’ (g.yung drung chi-myed). This final stage is an idyllic land endowed with all things required by humans and animals in the afterlife. In a text relating this tradition, Rnel drĭ ’dul ba’i thabs sogs (composed circa 850–1000 CE), it is a swastika deer that first opened the way to paradise.

The Bon expression for longevity and enduring good health is ‘swastika of life’ (tshe yi g.yung drung). This paradigm for human well-being is derived from an ancient understanding of the swastika as the primary source of life. The generative swastika is recorded in origin myths and in rituals featuring cosmogonic goddesses such as Grandmother Sky Queen (Gnam phyi gung rgyal) and White Sky Woman (Gnam sman dkar mo). By virtue of the swastika being the generative nexus in various origins myths of both literary and oral traditions in Tibet, it appears to have once been her premier cosmic symbol. As we shall see, this observation is buttressed by the rock art record of Upper Tibet.

The importance of the swastika in Buddhism and Bon and in the earlier religious traditions of Tibet is reflected in contemporary cultures of Tibet, where it has acquired significance comparable to that in the wider Eurasian world. The swastika in Tibet appears on houses, rugs, tools, tattoos, sashes, boot ties, hats and other articles of clothing as a symbol of good luck and prosperity. It also figures prominently as a sign of stability in rites of birth, marriage and death, and as a trope and metaphor in songs, poetry, folktales, and riddles.

Tibetan folk traditions, as much as Tibetan literary traditions, allude to the hoary history of the swastika, which long predates the Lamaist religions of Buddhism and Bon. Perhaps one of the most ancient living traditions is the association of the swastika with livestock offered to local deities to usher in happiness and security for individuals, communities and the countryside. In Upper Tibet swastikas made from butter are fashioned to anoint the heads of special livestock given to mountain and lake divinities as their personal property and as mounts for riding. In an origin myth for the gifting of livestock in a text composed in the 11th or 12th century CE (but incorporating earlier materials), entitled Mu ye pra phud phywa’i mthur thug, the swastika is an epithet for the Crystal Horned Conch Deer (Dung sha shel ru can). This archetypal stag was the bringer of all manner of good fortune (phywa and g.yang) to humans, including beautiful appearances.

Another tradition in both the popular and literary spheres thought to be of much antiquity in Tibet is the spread of barleycorn on altars in the shape of a swastika. According to Bon ritual tradition, this custom began with the propitiation of the chief god Gekhö (Ge khod) in the time of the Zhang Zhung kingdom. Making barleycorn swastikas to form the base of an altar (lha gzhi) is still commonly practiced by Bon and Buddhist spirit-mediums (lha pa) in Upper Tibet. This constitutes the most fundamental component of their offering regime.

Thus far, the oldest archaeological evidence for the swastika in Tibet appears in the rock art record of the western third of the Plateau. My research shows that the swastika arose there as a sacred symbol no later than the Iron Age, laying the foundation for it becoming one of the most loved and popular symbols in the Tibetan world. The swastika is a motif on ancient copper alloy talismans known as thokchas (thog lcags), some of which are of pre-Buddhist antiquity. Pile carpets of the 17th to 20th centuries also carry swastika designs. Older Tibetan textiles bearing the swastika must have been produced but they do not appear to have survived.

The origins of the swastika in Tibet are deeply veiled in the past. It is not yet known if this quintessential sign developed autochthonously or if it was introduced onto the Plateau by a foreign people. Painted pottery vessels and faience seals bearing the swastika appeared in the Indus River civilization more than 4000 years ago. However, the Himalaya were a formidable barrier to peoples and cultural influences reaching Upper Tibet from tropical India.

Likewise, the Andronovo, interrelated peoples of the steppe who swept across Central Asia all the way to the Pamirs and Kunlun in the Bronze Age, ornamented ceramic vessels with the swastika. The swastika is also widely distributed in the rock art of north Inner Asia. As with other aspects of shared material and artistic culture between Upper Tibet and countries to the north, common religious and mythological links may account for the swastika in the rock art of the broader region. If so, the Andronovo could have been responsible for its conveyance to Upper Tibet. It is hypothesized that the swastika in the petroglyphs of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia was a generative symbol for various tribes as well as having cosmic attributes. As demonstrated by folk and literary traditions in Tibet, similar functions can be entertained for the swastika in the rock art of Upper Tibet.

In Eurasian cultures the swastika was a well-known solar symbol, a formative cosmic element of various ancient religions on this biggest of continents. The solar connotations of the swastika help account for its predominance across many cultures over the long arc of time. Similarly, the swastika in Tibet is a solar symbol, one closely bound up with creative and cosmic impulses. The oldest Tibetan reference to the solar swastika I know of is found in the text Klu ’bum khra bo (probably first compiled in the 10th century CE). This text contains a myth of creation centered around a figure called Queen of the Water Spirits (Klu’i rgyal mo), the pantheistic goddess who fashions the universe out of her body parts. In this myth, the sun appears from the light rays of her left eye and is called the ‘unsurpassable swastika’ (g.yung-drung gyi bla-na med-pa).

Gallery of swastika photographs in Upper Tibet

Note: Swastikas depicted in this article are between 5 cm and 70 cm in height, with most between 10 cm and 30 cm in height.

We begin this photographic survey of rock art featuring depictions of the swastika as a cosmogonic device. There are nine instances of the swastika I have documented in Upper Tibet where it is accompanied by the sun and the moon. This type of composition is located at six different rock art sites spread across Upper Tibet from Lake Nam (Gnam mtsho) in the east to Guge (Gu ge) and Ruthok (Ru thog) in the west. Rock art featuring the swastika, sun and moon can be dated to the Iron Age (700–100 BCE) and Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 600 CE).* The wide geographic and chronological range of this distinctive ensemble of celestial symbols suggests that it played an essential mythological/religious role in ancient Upper Tibet.

Dates provided for rock art are estimates based on various criteria. On the dating of rock art in Upper Tibet and other western regions of the Tibetan Plateau, see various earlier works by the author, such as the August 2015 Flight of the Khyung.

The sun and moon, at least according to later Tibetan conceptions, are the primary female and male principles respectively. These principles are often articulated in tantric terms as the two main vectors of enlightenment, symbolized by the conjoined sun and moon (nyi zla). There is also a tantric and cosmological triad consisting of the sun, moon and stars (nyi zla skar gsum).

Rock art with the sun and moon appended to a swastika suggests that the latter was a central cosmogonic symbol, which may have represented the fount of existence in ancient Upper Tibet.* The sun and moon, powerful cosmic symbols in their own right, occupy a peripheral or subsidiary position in some compositions. One might read this alignment as portraying the swastika as the source or ruler of the sun and moon. In any event, this rock art anticipates the cosmogonic significance of the swastika in the later oral and literary traditions of Tibet. One can therefore postulate a deep historical origin for the swastika in Tibetan cultures and religions.

Sun-swastika-moon rock art has robust cultic and mythological affinities with cognate depictions in Spiti (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung, figs. 77–84).

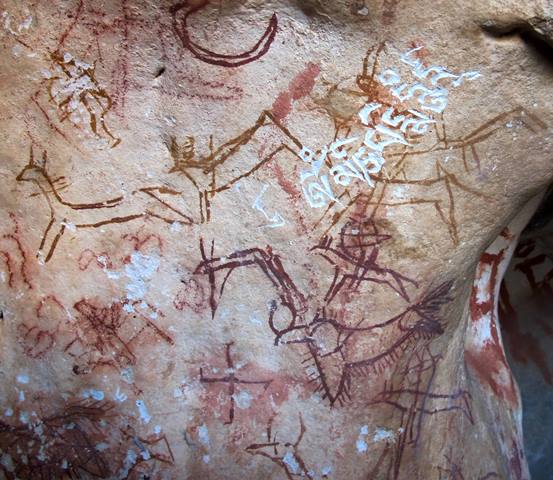

Fig. 1. The swastika accompanied by a sun probably of 13 rays and the crescent moon painted in red ochre (oxides of iron). Eastern Changthang. Iron Age. The light-colored lumps in the image are dabs of butter added by pilgrims.

Fig. 2. This carving of the crescent moon, swastika and sun is found in western Tibet. The sun with a spoked design is characteristic of Upper Tibetan rock art. Probably Iron Age.

Fig. 3. Sun, swastika and crescent moon below and to right of wild yak, western Changthang. The wild yak with its barbed belly fringe and large ball tail, and double curved horns was made in the same period or even as part of the same composition as the cosmic symbols. This rock is attributable to the Iron Age.

Above these rock art subjects is another triad of the crescent moon, swastika and sun that were more lightly carved. This other set of cosmic symbols appears to be of lesser (Protohistoric period) antiquity.

Fig. 4. Sun, swastika and crescent moon situated on top of a naturally occurring pillar of rock, northwestern Tibet. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

These three symbols are the uppermost subjects in an integral composition that includes petroglyphs of a pair of stepped shrines (the trident-like crowns of which are just visible in the image; they perhaps represent the world mountain), the horned eagle (khyung) and two anthropomorphic figures with avian features (possibly relating a clan theogony), tree, stag, wild yak, and tiger. All these figures are laden with religious, mythological and social significance in Tibetan cultures. This elaborate rock art composition with its iconic subjects may depict a mythic or idealized view of the cosmos, culture and lifeways of its makers.

Fig. 5. This panel of red ochre pictographs depicts two suns, crescent moon, two swastikas, conjoined sun and moon, and tree surrounded by dots. Northwestern Tibet. The various figures may have been painted at different times but are closely related thematically. Most seem to belong to the Protohistoric period; however, the conjoined sun and moon may have been made at a later date. The figures in this composition resonate with cosmological symbolism.

Fig. 6. Crescent moon, sun and swastika, western Tibet. In addition to having a few rays, the sun is divided by a cross into quarters. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 7. Swastika, sun and crescent moon lightly etched on a rock surface, northwestern Tibet. This triad of cosmic figures is the same as others depicted above, except that the swastika is oriented clockwise. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 8. Here again a swastika is flanked by the sun and crescent moon, western Tibet. As in fig. 6, the sun is divided by a cross into four sections. Figs. 2, 6, 8 are found at the same large rock art site.

The swastika is also depicted in the rock art of Upper Tibet with just one other cosmic symbol: the sun or crescent moon. It is likely that when depicted with just the moon the swastika assumed the identity of the sun. It is more difficult to comment on the symbolism of the sun and swastika dichotomy, or if it was even seen in such terms. The pairing of a solar or lunar sign with the swastika, as with the triad of cosmic figures examined above, must have conveyed profound meaning expressed in the cosmological, mythological or ritual arenas.

Fig. 9. A sun with 12 rays and a cross with bent legs in the disc, northwestern Tibet. Next to it are four interconnected circles, each of which contains smaller circles. Like the sunburst, these curvilinear subjects may have had cosmological symbolism. All of these carvings appear to form an integral composition. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 10. A possible birth-giving scene, northwestern Tibet. The sun and swastika signs were carved opposite an anthropomorphic figure with upraised arms and spread legs. Above the legs of this figure is a circle that may represent the womb. The petroglyph below the anthropomorph has not been identified.

All four carvings could constitute an interrelated composition, but given its somewhat varied physical appearance the sun (and markings to its right) may have been added at a later date. Be that as it may, the sun, swastika and anthropomorphic figure appear to convey a generative theme, as in birth-giving on either a cosmic or personalized level. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 11. Two swastikas, tree and sun, western Changthang. The swastika on the left has legs oriented in the same direction on each axis, interrupting the radial symmetry of this geometric form. Swastikas with legs out of sync are commonplace in the early rock art of Upper Tibet. These kinds of eccentric swastikas are still seen occasionally in contemporary Tibetan folk art. Probably Iron Age.

Fig. 12. Swastika and crescent moon, central Changthang. These two subjects appear to constitute a single composition. Iron Age.

Fig. 13. Swastika connected to crescent moon, central Changthang. Figs. 12 and 13 are found at sites situated more than 200 kilometers from one another. Iron Age or ProtohistorIc period.

The swastika is also commonly found among wild animals and other sacred subjects. In this context, it appears to symbolize the sun and act as a good-fortune bestowing agent for other subjects within its ambit. Diverse styles and techniques of productions characterize this rock art, indicating that it was made by different peoples in different times. There are few signs of obvious economic activity (e.g., hunting, pastoralism, transport) in this type of rock art. Thus other areas of the human imagination and endeavor seem to be involved.

Fig. 14. Here the swastika is situated amid an assortment of key figures, among which is a sun, crescent moon, two trees, what may be an anthropomorphic couple, wild yak and several other wild herbivores, archer, a row of four triangular forms (ritual structures?), and a raptor with outstretched wings. Eastern Changthang. Protohistoric period.

Most of these varied figures appear to have been painted by the same artist. Like fig. 4, this rock art conveys an encompassing picture of the life and culture of its maker. The array of protean symbols (sun, moon, swastika, tree), vital economic structures (wild ungulates, hunter), cultic emblems (raptor, triangular forms), and social constructs (couple) furnish us with an extraordinary view of ancient Upper Tibet. The functional categories suggested for these subjects should not be seen as mutually exclusive.

Fig. 15. Swastika, animal and highly obscured figure(s) set between two primitive stepped shrines. Another red ochre swastika is visible on the right side of the image. Protohistoric period. Although several different compositions may be involved, the swastika and other pictographs were made in the same general period and communicate interrelated religious themes.

Fig. 16. Swastika surmounted by teardrop-shaped figure and stag. Protohistoric period or Early Historic period (600–1000 CE).

The significance of this attractive composition remains enigmatic. It appears to depict the stag in a cultic context, one imbued with mytho-ritual symbolism. The deer is probably the single most important animal in the archaic mythic and ritual literature of Tibet.

Fig. 17. Two wild ungulates flanking a swastika, central Changthang. Protohistoric period. The lower left animal may possibly be a horse with a rider or something else on its back.

Irrespective of whether the three figures comprise an integral composition, these petroglyphs communicate the intimate association of wild animals with the swastika in Upper Tibet, a relationship still evident today in herding and hunting activities.

Fig. 18. Large wild yak with double-curved horns, humped withers and wedge-shaped tail, western Tibet. Probably Iron Age. Three swastikas (and others not shown) surround the wild yak as well as one yak above (also seen in photo) and one below it.

These swastikas were added at by various individuals probably for ritualistic or devotional purposes. The wild yak remains one of Tibet’s holiest and most important animals, featuring in numerous myths, rituals and narratives. Many elemental, personal and territorial spirits appear in the guise of wild yaks in Upper Tibet.

Fig. 19. Wild yak paired with a swastika at same site as fig. 18. Probably Iron Age.

Fig. 20. Two swastikas and two wild yaks (specimen on right partly visible in image). Protohistoric period. Here once again the link between the wild yak and swastika is demonstrated.

As a symbol of good fortune and fecundity, it is possible that swastikas were added to such rock art to increase the supply of game animals, insure their well-being, as tokens of thanksgiving and appreciation, or as a seal marking the source of sustenance for local inhabitants and wildlife.

Fig. 21. Swastika as centerpiece with two or more wild ungulates and possibly other swastikas around it. Northwestern Tibet. These petroglyphs have been obscured by the subsequent removal of the stone surface. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 22. A swastika, animals and curvilinear figures can be discerned while other carvings on the rock panel are highly obscured. The compositional relationships between these petroglyphs is unclear. Northwestern Tibet. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 23. Swastika and several wild ungulates that appear to have been produced at one time, northwestern Tibet. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 24. Swastika and stick figure animal, Eastern Changthang. These two figures and perhaps others in this small cave may have been created by the same painter. The naïve form of the animal is in keeping with later styles of rock art. Early Historic period.

Fig. 25. Swastika and animals, western Tibet. Here again we see figures belonging to a decadent phase in rock art. Early Historic period.

The swastika in Upper Tibet rock art also appears in compositions or in close proximity to other subjects, where thematic interrelationships are not always clear. This kind of rock art supplements in unknown ways the semantic scope of the swastika, the most common and versatile symbol in Upper Tibetan rock art. Some swastikas appear in close proximity to hunting activities. The range of possible functions for this puissant sign in hunting rock art includes good luck charm for obtaining game animals, post-hunting thanksgiving token, and symbol of the cosmic or mystic source of animals, etc.

Fig. 26. In the lower center portion of the image there is a swastika with very short legs, an archaic manner of depiction in Tibet but one that has survived in folk art. All around the swastika are other figures in a small cave pullulating with red and yellow ochre pictographs. This image includes two different hunting scenes, where archers on horseback and a wild yak, stag and other wild ungulates are featured. Some of the animals have been struck by arrows as hunters come in for the final kill. However, it is not clear that the swastika was painted as a deliberate part of these venatic scenes. It may form a separate subject, as does the triad of cosmic symbols in the same cave (fig. 1). Eastern Changthang. Most pictographs shown are of Iron Age antiquity.

Fig. 27. What appears to be a swastika depicted in isolation in the same cave as figs. 1 and 26. Nevertheless, a welter of other figures is not far away. Note the use of both yellow and red ochre. Eastern Changthang. Iron Age.

Fig. 28. What appears to be a yak rider coursing a wild yak. There are no weapons discernable so this does not seem to be a hunting scene. The swastika below the wild yak being pursued and an unidentified subject below the rider complete this integral composition. This swastika is presented with its axes and legs turned at a 45° angle, a far less common orientation in Upper Tibetan rock art.

Unlike northeastern Tibet, yak riding was not a common traditional pursuit in Upper Tibet, a land where larger, more robust animals are the pastoral norm. Nevertheless, it is not known whether this ethnographic fact is applicable to the ancient past. Perhaps this rock art narrates a tale or chronicles a ritual action, but as with many other interpretations of swastika rock art, this cannot be corroborated.

Fig. 29. Two swastikas, three wild yaks and what appears to be a horse rider (left side of image), central Changthang. Protohistoric period.

It is not clear what kind of theme is being portrayed in this composition. The horseman, arms raised, does not appear to be wielding weapons. It might be speculated that this is some kind of victory demonstration or a paean paying tribute to the ancient way of life where horsemen consorted with wild yaks.

Fig. 30. A boulder with two swastikas facing in opposite directions (upper left side), three chariots (only one wheel and draught animals visible in right hand specimen), tiered shrine with bulbous upper section (superimposed on one of the chariots), design of interlinking triangles (superimposed on top of the shrine), and other less distinctive subjects, most of which appear to have been carved in the same time frame. Western Tibet. Late Bronze Age (1200–700 BCE) or Iron Age.

Perhaps the swastika petroglyphs represent the sun, the chariot too having solar associations in Indo-European mythology. The chariot was almost certainly an import from north Inner Asia, with Xinjiang as its most likely geographic source. It is in such a pictorial context that the wider regional mythological and religious significance of the ancient swastika is likely to have been expressed in Upper Tibet.

Next Month: The continuing saga of the revered swastika in Upper Tibetan rock art!