March 2015

John Vincent Bellezza

The Prehistoric collection of the Tibet Museum in Lhasa – Part Two

Welcome, as Flight of the Khyung continues with a bird’s eye view of the Tibet Museum and its prehistoric collection of artifacts. This month’s feature peruses the ceramics and metal objects on view at Tibet’s premier cultural museum. So without further ado, let us fly away to a remote period in Tibetan history.

An Introduction to the Neolithic Ceramics of Kharub

The most extensive ceramic assemblage from Neolithic Tibet discovered to date comes from Kharub (Kha-rub), where approximately 20,000 vessels and shards of pottery were documented. These ceramics were recovered from deposits with a fairly secure chronology, and have been dated to circa 3300 to 2000 BCE.

The stone tools and ceramics of Kharub share a few stylistic and technical affinities with those of Neolithic cultures from the Yellow River basin, particularly the Yangshao culture (circa 4800–3000 BCE) and Majiayao culture (circa 3800–2000 BCE). There are also faint similarities between the ceramics of Kharub and pre-Harappan sites such as Kunal, Haryana. Nonetheless, the Neolithic ceramic vessels from the upper Yellow River valley, Sichuan basin and northern Indo-Gangetic plains form distinctive classes of material objects, which are different in character to those of Kharub.

When considered together, the attributes (petrological properties, characteristic forms, and decorative features) of the Kharub ceramics constitute a distinctive class of material culture. The ceramic tradition of Kharub belongs most closely to the remains of Neolithic cultures found in the central and northeastern portions of the Tibetan plateau.

Thus, even 4000 or 5000 years ago, the cultural differentiation of the Tibetan plateau from surrounding regions was already well underway. Evidence from the ceramic assemblages and other material supporting evidence from the Plateau make it permissible to speak of the Tibetan Neolithic or Neolithic cultures of Tibet.

The majority of Kharub pottery is composed of unglazed coarse yellowish-brown ware and red ware. Surface decorations include cord-marked, incised, stamped and punctated geometric designs, as well as some appliqué work. These types of decorations were created when the vessels were in their green or unfired state.

The ceramics of Kharub (figs. 52–67) were hand-worked by wrapping coils of kneaded clay around in circles and placing one on top of the other to produce the desired shape of a vessel. The coils of clay were then melded by pinching and probably with a paddle or scrapper. A paddle and anvil must have been used to thin the walls of some vessels. The vessels of Kharub are classed as earthenware (a softer, more porous type of ceramic). They were pit-fired (open-fired) using wood and animal dung as fuel. Thus the vessels were fired at relatively low temperatures (around 700–900° C), using fairly low-quality clays. A more comprehensive analysis of the chemical composition of these ceramics would help in better understanding the precise temperatures involved in firing. This, in turn, would furnish clearer insights into the methods of production.

Most of the ceramic vessels discovered in Kharub were used for various domestic functions. It is also possible that certain vessels may have had funerary ritual functions. As the relational analysis (stratigraphic and planar) of materials excavated at Kharub was not fully completed, potential information on cultural and economic patterns and processes underpinning the settlement over time has not been forthcoming. There is still much work to do if Kharub and other Neolithic sites in Chamdo are to yield a more clearly defined picture of prehistory in Eastern Tibet.

A Photographic Gallery of Neolithic Ceramics from Kharub in the Tibet Museum Collection

In the captions of photographs shown below, I supplement the basic information provided in the Tibet Museum displays of artifacts with my own descriptions. The trilingual museum labels (in Tibetan, Chinese and English) are usually restricted to location, type of object and age. My comments and observations are also sometimes appended below the captions.

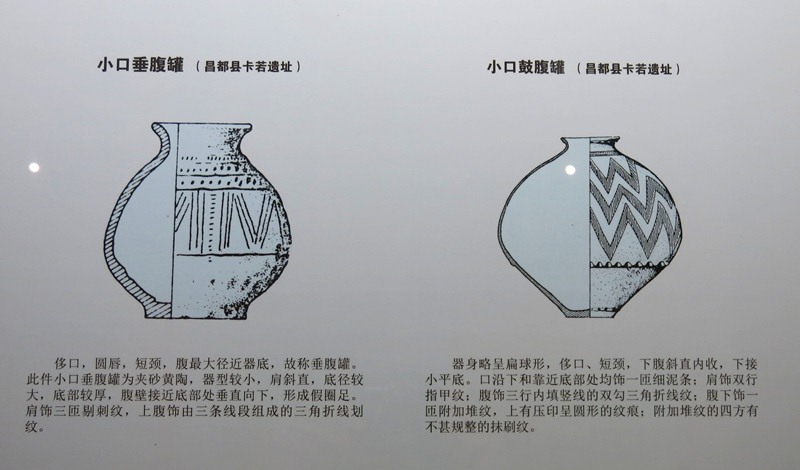

Fig. 52. Diagrams of the design and thin and thick wall structure of ceramic jars with globular bodies, narrow necks, flared lips and flat bottoms, and exhibiting incised, stamped and punctated geometric designs on the exterior.

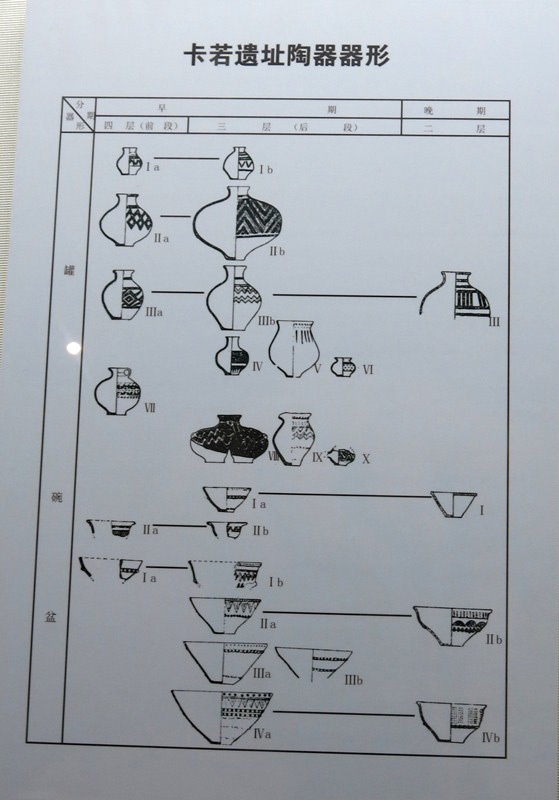

Fig. 53. Diagrams of ceramic typologies found at Kharub, Chamdo. There are jars, bowls and basins and a variety of incised, stamped and cord-marked decorations represented.

Fig. 54. Globular reddish-buff ware jar with constricted neck, flared rim and flat base. Incised triangles cover the body of the vessel and a lineal motif was stamped into the shoulder and neck of the vessel. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

The black patches visible on the vessel may possibly be ‘fire clouds’, which form when a ceramic comes into contact with unburnt fuel after a fire is smothered, in order to darken the color of the fabric.

Fig. 55. A globular jar of reddish-buff ware with truncated lower section and flat base. At the bottom of the body is a band of punctates. Incised geometric designs consisting of graduated triangles are found on the body, while rows of lines were graved on the shoulder and relatively long neck of the jar. The lip of the jar is somewhat flattened. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 56. A short-necked bulbous jar of yellowish-brown ware with a flat base. The neck merges imperceptibly with the shoulder of the vessel. An appliqué undulating band encircles the lower body of the vessel. Incised lines and punctates embellish the body of the jar. The lip is collared and slightly flattened. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 57. A globular vessel of reddish-buff ware, with incised geometric decorations, short constricted neck and thick rounded lip. There is a large spout or aperture in the middle of the vessel, which may possibly indicate that it functioned in the preparation of a fermented beverage. The white areas of the vessel are reconstructed portions built to aid in understanding its original form. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 58. A red ware bowl with a slightly flaring rim. Note the incised lines encircling the top portion of the vessel. The dark area in the foreground is a reconstructed portion of the vessel. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 59. A sub-conoidal basin of yellowish-brown ware with a flat base. In addition to incised triangles on the upper portion of the body, the rim of the basin exhibits dentate stamping. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 60. A smaller red-ware bowl with everted rim. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 61. A globular jar of yellowish-brown ware, with incised geometric decorations on the body, truncated neck, rounded lip and sub-conoidal base. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 62. A globular jar of yellowish-brown ware, with incised lines forming bands and ovals, short neck, prominent rounded lip, and flat base. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 63. A red ware globular jar, with incised geometric designs on the body and flat base. The neck of this vessel is constricted and relatively long, and the lip is flaring. An appliqué dentate band engirds the neck. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 64. A globular jar of yellowish-brown ware, with incised vertical and horizontal linear decorations, short, straight neck, everted rim, and flat base. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 65. A large bowl of dark-gray ware, with incised designs on the body and sub-conoidal base. Below the rim of the vessel, the body is a series of punctates arranged in vertical lines. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

According to the museum label, this vessel was sand-tempered. From a visual appraisal of this ceramic alone, it cannot be determined whether opening materials were actually added to the clay before firing.

Fig. 66. An ellipsoidal jar of dark-gray ware, with tapering lower body, flat base, flaring lip, and open spout. Decorations were made through incising and with punctates. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 67. A highly unusual double-bodied jar of red ware, with two zigzag bands of incised decorations around the bodies, flat bases, short neck, and broad, flattened rim. Note the lugs on the two sides of the vessel. This jar with its ellipsoidal bodies was mostly covered with black (manganese oxide) and red (iron oxide) paints. Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

An Introduction to Neolithic Ceramics from Chugong

We will now examine the ceramics from Chugong (Chu-gong), a site on the northern edge of the Lhasa valley. The first major period of pottery from Chugong dates to the late phase of the Neolithic, circa 2000 to 1500 BCE.

The late Neolithic pottery of Chugong (figs. 68–83) belongs to a more mature or advanced stage in the development of ceramics on the Tibetan plateau than does the assemblage from Kharub. The Chugong site is believed to be 500–1800 years more recent, and a number of technological refinements took place during that time. The late Neolithic ceramics tradition of Chugong did not appear in a vacuum: centuries of more primitive pottery production (such as the Kharub type) are likely to underpin it. However, sites from the early and middle phases of the Neolithic are not yet well documented in Central Tibet.

The late Neolithic ceramics found at Chugong are characterized by finer fabrics, refined forms, building on a wheel (some are also hand worked), burnishing, and adeptly made lug handles. The pottery tradition of Chugong is dominated by red ware and dark-gray ware.

The finer fabric ceramics from Chugong are, in part, a result of firing at higher temperatures than those used to produce the Kharub vessels. This indicates that kilns were employed rather than open pits for firing. Kilns allow clay to be heated slowly at first, gradually eliminating water, thus reducing the chance for fire spalls and the bursting of vessels. The use of kilns also helps reduce the risk of dunting or the formation of cracks from the too rapid cooling of a finished vessel.

Many of the vessels at Chugong were burnished, a polishing process that takes place after the greenware or unbaked clay has dried to the consistency of hardened leather. After firing, burnished ceramics will have a glossy, smooth and hard surface and may be more water-proof. Typically, a smooth pebble or potsherd is used to burnish pottery. The telltale marks of burnishing are a variable luster and polishing marks left behind on the surface of the vessel.

A Photographic Gallery of Neolithic Ceramics from Chugong in the Tibet Museum Collection

Fig. 68. A collection of ceramic from the Chugong site near Lhasa. Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

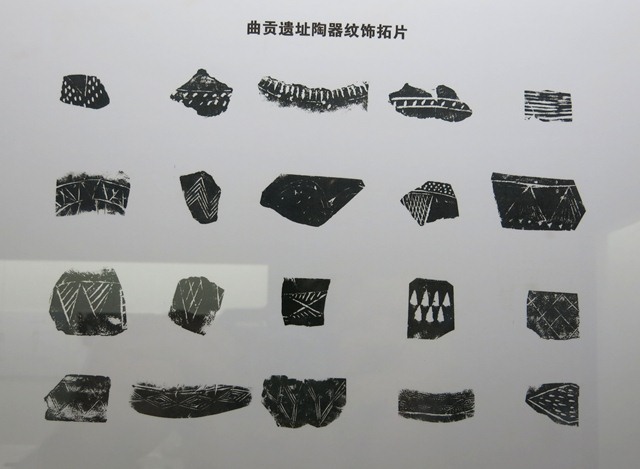

Fig. 69. The various types of decorations (cord-marked, incised, stamped, punctated) found on vessels from Chugong, Lhasa. Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 70. A burnished dark-gray ware bowl, with splayed foot and single strap handle. Note the incised diamonds on the lower body of the bowl and the fluting on the foot, an attribute created during the modeling of the vessel. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 71. A burnished globular jar of gray-ware, with single strap handle set high on the wide, short, straight neck, and with a slightly flaring rim. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 72. A burnished dark-gray ware globular jar, with single loop handle and a short, straight neck. The darker area in the foreground is a reconstructed portion of the vessel. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 73. A burnished globular jar of red ware, with a band of incised triangles encircling the middle of the body, wide, ribbed neck, strongly flaring lip. For display, the strap handle on the middle of the body and some other parts of this vessel have been reconstructed. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 73. A burnished globular jar of red ware, with a band of incised triangles encircling the middle of the body, wide, ribbed neck, strongly flaring lip. For display, the strap handle on the middle of the body and some other parts of this vessel have been reconstructed. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 75. A simple bowl of dark-gray ware, with single groove circumscribing the middle of the body. Chugong, Lhasa, Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 76. Dark-gray ware bowl, with outwardly tapering body, small foot and slightly turned-out rim. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 77. Bowl of dark-gray ware with collared rim. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 78. A burnished globular jar of dark-gray ware, with a wide neck, flaring lip and two lug handles. The body is adorned by punctates aligned vertically. Note the molded bead encircling the middle of the body. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 79. A burnished dark-gray globular jar, with wide, outwardly tapering neck, attenuated lip, and two strap handles. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 80. A bulbous dark-gray ware jar of more rudimentary construction. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 81. A gray ware jar, with bulbous body, short neck, flaring lip, and two straps handles set horizontally along the middle of the vessel. This jar is covered in an intaglio herringbone pattern visible inside and out. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 82. A burnished dark-gray ware globular jar, with a very short, straight neck, and two strap handles set high on the shoulder and neck. Along the shoulder are two incised bands of triangles and punctates. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 83. A burnished brownish-gray ware globular jar, with two loop handles and everted rim. On the side of the vessel facing the viewer are two incised triangular embellishments. Chugong, Lhasa, late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

An Introduction to Later Ceramics from Chugong

In the Tibet Museum’s prehistoric collection there are also a number of ceramic vessels attributed to the highly inclusive “pre-Tubo period”. Chinese archaeologists and historians use the term “Tubo” to refer to the Tibetan Imperial period (circa 650–850 CE). The term “pre-Tubo” in Tibetan is translated by the museum as “Tsenpoi Gyalrab” (Btsan-po’i rgyal-rab), which denotes the dynasty of Central Tibetan kings (btsan-po) and therefore can be dated to circa 100 BCE to 650 CE.

In my writings, I refer to this era of pre-Imperial Tibetan (Spu-rgyal bod) rulers as the “Protohistoric period”, because of its ample coverage in later Tibetan literature, the occurrence of epigraphs on the western margin of the Tibetan plateau in this period, legends of a system of writing in the Zhang Zhung kingdom, and the possible prealphabetical usage of the letter A as a magic symbol or cipher.

In practical terms, the Chinese term “pre-Tubo” does not always synchronize with the Tibetan “Tsenpoi Gyalrab”. “Pre-Tubo” is sometimes used as a more inclusive measure of time, anytime, in fact, between 1100 BCE and 650 CE. The first half of this huge span of time is also called the “Metal Age” by Chinese archaeologists. In more conventional terms, “pre-Tubo” can potentially include the Late Bronze Age (circa 1100–900), Early Iron Age (circa 900–600 BCE), Iron Age (circa 600–100 BCE), and Protohistoric period (circa 100 BCE to 600 CE).

The information provided in the exhibits of the Tibet Museum (as well as in many Chinese archaeological publications does not specify how the label “pre-Tubo” is being used in a particular archaeological context. That such an expansive chronological purview can be denoted by the term is indicative of a black hole that remains in the study of archaeology in Tibet. Many artifacts in the TAR were recovered with few if any scientific controls, as a kind of sanctioned treasure hunting or salvage operation. While it is laudable that many cultural relics were spared from destruction in this way, much potential scientific information has been lost.

Chugong is a good case in point: when researchers from the TAR Bureau of Cultural Relics and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences first visited the site in the 1980s, it was already heavily disturbed by erosion, as well as by excavations carried out to collect earth and gravel for construction projects. Chugong has also been plagued by illegal treasure hunting. Around half of the estimated one-hectare site remains poorly studied by archaeologists. Around three dozen tombs were discovered in close proximity to the residential remains of Chugong. Unfortunately, it has not been determined which of these tombs might date to the Neolithic and which ones belong to the Bronze Age and other less remote periods in Tibetan history. This muddling of the archaeological record has been repeated at many other sites in the TAR.

At this time, I am able to offer few insights into the chronology of “pre-Tubo” ceramics from Chugong and other sites in Tibet. In the captions below, I simply gloss these objects “pre-Imperial period”. It is, of course, imperative that a typology of the different groups of ceramics in Tibet is assembled in a consistent and verifiable manner. This will require more systematic archaeological exploration and the establishment of firm chronological signposts by which ceramic types and their specific attributes can be assessed.

The so-called pre-Tubo ceramics from the highly disturbed Chugong site (figs. 84–92) are a fairly diverse group and appear to represent different periods of production. These unglazed, mostly red ware ceramics are characterized by simple forms and an absence of decoration. These utilitarian vessels were probably used mainly for the storage of foodstuffs, cooking and dining. In most instances, they are more crudely made than the late Neolithic ceramics of Chugong. Many of the pre-Imperial examples have coarser textures and are irregularly walled. This suggests that these vessels may have been manufactured on a larger scale than the earlier assemblage. Also, the wider range of “pre-Tubo” (pre-Imperial) forms seems to point to a more diversified technological regime and social environment than those prevailing in the late Neolithic.

A Photographic Gallery of Later Ceramics from Chugong in the Tibet Museum Collection

Fig. 84. A globular red ware jar with almost no neck and flaring lip. Note the thumb rest on the single loop handle. Chugong, Lhasa, pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 85. A circular red ware cup, with almost straight walls and ring handle with thumb rest. Chugong, Lhasa, pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 86. A globular jar of red ware, with a curved neck and large, open spout. The handle of this jar has been broken off. Note the inclusions in the fabric of the vessel. Chugong, Lhasa, pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 87. An ovoid red ware jar with a single squared handle. Chugong, Lhasa, pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 88. A deep bowl of red ware, with an everted rim, and what appears to be a single handle in the rear. Chugong, Lhasa, pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 89. A barrel-shaped jar of reddish-buff wear, with single loop handle with thumb rest and flat base. Chugong, Lhasa, pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 90. An ellipsoidal red ware jar with a wide mouth and flaring lip. Chugong, Lhasa, pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 91. A simply designed gray ware bowl. Chugong, Lhasa, pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 92. A wide-bodied jar of red ware, with sloping shoulder, turned-out rim and two lug handles. Chugong, Lhasa, pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 93. A plain red ware bowl of crude construction. Chugong, Lhasa, pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

A Photographic Gallery of pre-Imperial Period Ceramics from Other Regions in the Tibet Museum collection

The ceramics in this section belong to five different sites spanning the eastern, central and western portions of the TAR. A variety of vessels and one sculpture are depicted here (figs. 94–108). These ceramics are likely to date to various time periods. As explained above, such objects are all lumped together under the label “pre-Tubo (pre-Imperial) period”. Ceramics discovered by Chinese and Tibetan archaeologists at a number of different cemeteries in Tsang and Ngari (Western Tibet) are not exhibited in the Tibet Museum.

Fig. 94. A red ware globular jar, with ribbing on the body, inflected shoulder, fairly long and wide neck, and flaring rim. This vessel was recovered from the stone chamber (cist) of a tomb in Gonjo (Go-’jo) county, Chamdo prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

According to the English description on the label accompanying the ceramic jar, the tomb is described as “Xiangbei”. This seems to refer to the Xianbei, a Mongolic people who formed a large state in the early first millennium CE. This state had interactions with the Tuyuhun and Chiang tribes on the northeastern edge of Tibet. Cist tombs of the “steppe type” are reported to have been discovered in Kham. However, the vessel recovered from this tomb is of a type with clear Tibetan precedents. Other specimens carrying the same geographic and cultural attribution (figs. 96–100) form a distinctive group of ceramics, distinguished by very large strap handles attached high up on the vessel.

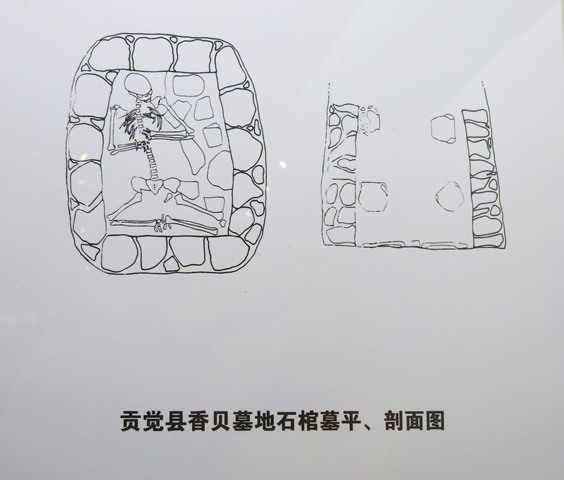

Fig. 95. A diagram of a cist tomb in Gonjo county where some of the vessels illustrated in this article were discovered. Their deposition in a tomb indicates a funerary ritual function. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 96. A wide-mouthed ellipsoidal jar of burnished dark gray ware, with a single strap handle, flaring rim and rounded lip. There is a band of incised diagonal lines engirding the middle of the body of the vessel. Discovered in a “Xiangbei” stone-chambered tomb, Gonjo county, Chamdo prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

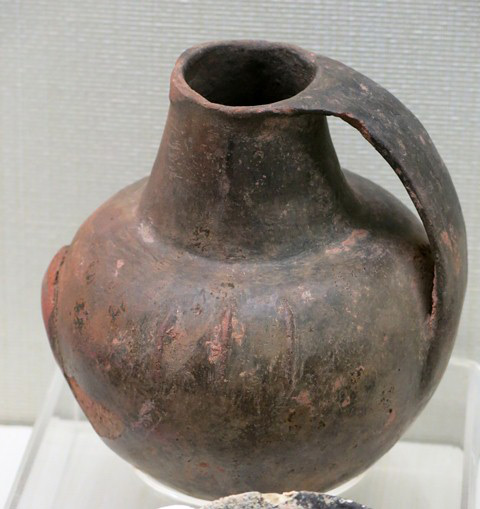

Fig. 97. Globular jar of burnished reddish-buff ware, with long, tapering conoidal neck, and large strap handle attached to the rim and the middle of the body of the vessel. Found in a “Xiangbei” stone-chambered tomb, Gonjo county, Chamdo prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 98. Globular jar of reddish-buff ware, with two large strap handles attached to the rim. Found in a “Xiangbei” stone-chambered tomb, Gonjo county, Chamdo prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 99. Globular jar of reddish-buff ware with two large strap handles attached to the rim. A punctated ribbon encircles the middle of the vessel. Found in a “Xiangbei” stone-chambered tomb, Gonjo county, Chamdo prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 100. Wide-mouthed globular jar of burnished dark-gray ware, with two large handles, ribbing spaced at wide intervals around the body, a line of incised V-motifs on the shoulder, and molded fluting encircling the neck. Discovered in a Xiangbei stone-chambered tomb, Gonjo county, Chamdo prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 101. Unburnished red ware bowl with a wide foot and slightly tapering sides, and loop handle flattened on top. Found in a tomb (bang-so) in “Buma Cemetery”, Ngamring (Ngam-ring) county, Shigatse prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 102. A well-formed, cord-marked or fabric-impressed (producing a dappled effect) red ware amphora, with small loops surmounting the lug handles, and a wide flaring mouth. Ngamring county, Shigatse prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

This amphora shares affinities in form, fabric and decorative treatment with ceramics from Guge, dating to the Iron Age (600–100 BCE) and Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE). Cord-marked and other types of impressions function variously to keep a paddle from sticking to the surface of a green vessel, for increased structural strength, for gripping during use, and to create more surface area for intensification of heat transfer when used for cooking.

For a couple of examples of Protohistoric period ceramics from Gurgyam, see the October 2010 Flight of the Khyung. Also see figs. 106, 107 infra. A more detailed study of ancient Western Tibetan ceramics will form another issue of Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 103. Burnished dark-gray ware globular jar with long tubular neck and flattened lip. A band of incised lines girdles the middle of the body of the vessel. This jar has a slightly curved spout that is longer than the neck, which terminates in a flange-like lip. This jar was discovered in a “Xialamu” cist tomb, Lhuntse (Lhun-rtse) county, Lhokha. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 104. Burnished dark-gray ware globular jar, with medium-length neck and flaring rim. A band of incised chevrons rings the shoulder of the vessel. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 105. Red ware bowl, with a bulbous body, straight neck and single loop handle. Ngam-ring county, Shigatse prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 106. Wide-mouthed globular jar of red ware, with a short neck, two strap handles, rounded spout, and cord-marked treatment. This vessel was discovered in the “Kaerbu” (Tibetan = Mkhar-bu?) cemetery, Guge, Western Tibet. Iron Age. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 107. Bulbous red ware jar, with a long and wide neck, prominent, partially closed spout, variable-shaped handles (angular handle on one side and a double handle with angular and loop forms on the other side), and cord-marked or fabric-impressed treatment of the surface. “Kaerbu” cemetery, Guge, Western Tibet. Iron Age. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 108. A ceramic tortoise sculpture. From the “Baishan” cemetery, Sakya (Sa-skya) county, Shigatse. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Supplement added March 2016: Reportedly, this is actually a dough figure unearthed at the Gepel (dGe-dpal) cemetery, Sakya County. This dough tortoise was placed with charcoal inside a ceramic vessel. It is thought to have probably been a ransom offering in lieu of blood sacrifice. It is attributed to the “Tubo period” (in this work, expansively dated from 3rd century BCE to 9th century CE). See p. 211 (fig. 123) of Zla-ba tshe-ring, Suo Wenqing, dBang-’dus, and bSod-nams dbang-ldan. 2000: Precious Deposits: Historical Relics of Tibet, China. Beijing: Morning Glory Publishers.

A Photographic Gallery of pre-Imperial-Period Metal Objects from Various Regions in the Tibet Museum collection

The Tibet Museum houses a small but diverse collection of metallic objects dating to the pre-Imperial period (pre-7th century CE). This was a formative epoch in Tibetan civilization, bridging various phases of its cultural, political, economic and technological development. With the exception of the west, where Chinese, Tibetan and foreign archaeologists have uncovered a considerable body of evidence for the Iron Age and Protohistoric period, relatively little research and exploration of this pivotal era has been conducted in Tibet.

For the horse bridle in the center of the photograph, see August 2014 Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 110. A pair of silver earrings from a stone-chambered tomb, Gonjo (Go-’jo) county, Chamdo prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 111. Bronze knife blades from a stone-chambered tomb, Gonjo county, Chamdo prefecture. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

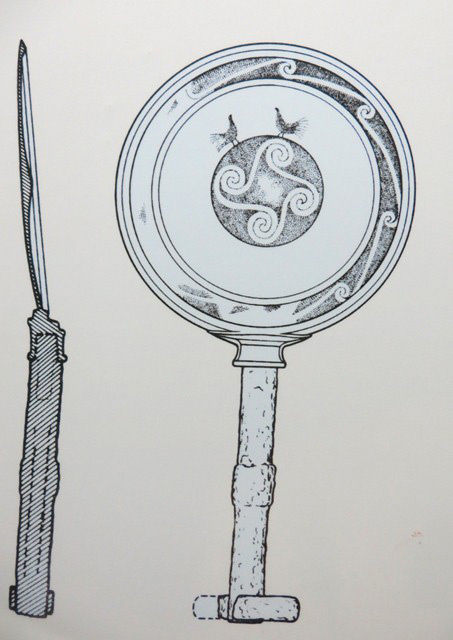

Fig. 112. The body of a copper alloy mirror with a handle. The engraved volutes in the center of the mirror are visible. Chugong, Lhasa. Pre-Imperial period. Tibet Museum collection.

This mirror was over cleaned a few years ago and has still not been properly stabilized.

The mirror from Chugong is very similar to two specimens illustrated in the December 2014 Flight of the Khyung, figs. 5, 6. The style of volutes in the outer band of the Chugong mirror is a decorative feature shared in common with the mirror in fig. 6. Also, the sockets connecting the handle to the mirror, as well as the elevated rim, in all three examples under review here are of the same design and workmanship. However, the mirrors in figs. 5 and 6 of the 2014 December newsletter have a distinctive circular nub or nipple in the center, while the center point of the Chugong mirror is only slightly raised. A unique feature of the Chugong specimen are the two engraved birds situated above the central ring (I still have not been able to discern them). The central ring itself is adorned with an engraved quadpartite volutes motif reminiscent of a swastika.

From the purported place of discovery of the mirror in fig. 6 of the December 2014 Flight of the Khyung and another one of this typology recently found in Western Tibet, as well as taking into account the volutes decorative treatment of all three engraved mirrors mentioned in that newsletter, I provisionally identify them as being of Upper Tibetan origins. Nevertheless, the discovery of the Chugong specimen in situ in a tomb may indicate that these mirrors, or least certain ones among them, were produced in Central Tibet. It must be noted that Mark Aldenderfer and Zhang Yinong’s belief that the Chugong mirror was made in Central Asia (2004: 32) is not warranted.*

Aldenderfer, M. and Zhang Yinong. 2004. “The Prehistory of the Tibetan Plateau to the Seventh Century A.D.: Perspectives and Research from China and the West Since 1950” in Journal of World Prehistory, vol. 18 (no. 1), pp. 1–55. Springer: Netherlands.Unfortunately, it appears that no chronological data were compiled for the tomb from which the Chugong mirror was recovered. Two of the engraved mirrors in the December 2014 Flight of the Khyung are dated by Namgyal G. Ronge to 800–300 BCE. Huo 1994; Huo 1997; IOA 1999; and Zhao 1994 (after Aldenderfer and Zhang 2004: 32) attribute the Chungong example to 800–500 BCE. Amy Heller more conservatively places one of the specimens shown in the December Flight of the Khyung in the 200 BCE to 200 CE period. Pending further information, I think it is best to assign all of the copper alloy mirrors with engraved volutes discussed in this article to 500 BCE to 200 CE (Iron Age or early Protohistoric period).

Fig. 114. Double-edged copper alloy dagger, with fine embossed designs on the hilt and on the end of the handle. Note the full-length blade spine. Found in a tomb at the Gyaling (Rgyal-gling) cemetery, Guge, Western Tibet. Iron Age. Tibet Museum collection.

For more on this dagger, see the July 2010 Flight of the Khyung. For a very similar dagger said to have been found in Sichuan illustrated on a commercial website, see:

http://www.icollector.com/Ancient-Bronze-KNIFE_i10234892

The two knives referred to here are of Tibetan or possibly northeastern Inner Asian origins.

Fig. 115. Two copper alloy buckles or rings for attachment, with a pair of confronting fish. Early Historic period (650–1000 CE) or Vestigial period (1000–1300 CE). Tibet Museum collection.

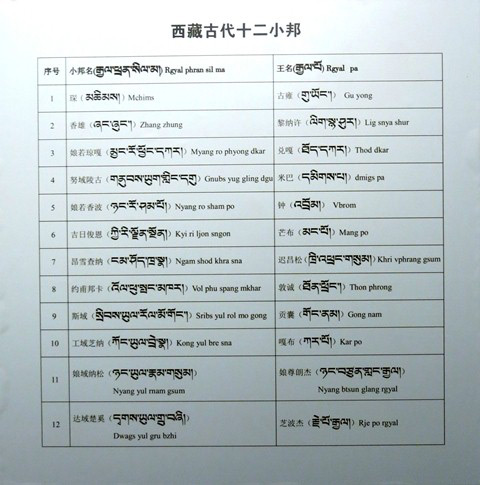

Fig. 116. A chart of the Gyalchen Cunyis (Rgyal-chen bcu-gnyis), the twelve principalities and twelve rulers of pre-dynastic Central Tibet. Tibet Museum collection.

A Photographic Gallery of the Rock Art Exhibition in the Tibet Museum collection

The Tibet Museum has a number of photographs of rock art on display. They have also constructed an artificial rock wall showing how petroglyphs are distributed on stone surfaces. I have chosen just a small range of materials for presentation here.

Only a portion of the rock art sites recorded in Western Tibet is shown on this map. For a more complete listing of sites see:

Bruneau, L. and Bellezza, J. V. 2013: “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’”, in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28 (December 2013), pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS: http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf

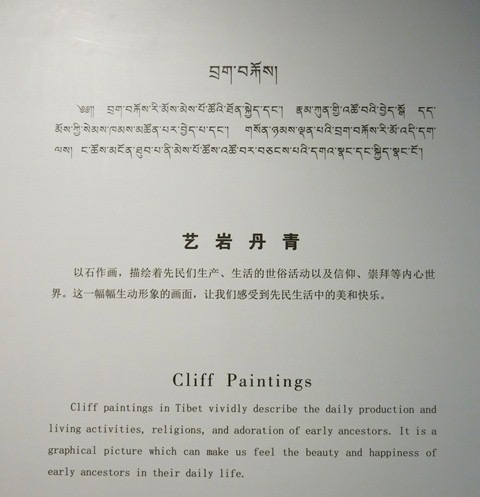

Fig. 118. A placard describing rock art in the three languages used in exhibits at the Tibet Museum.

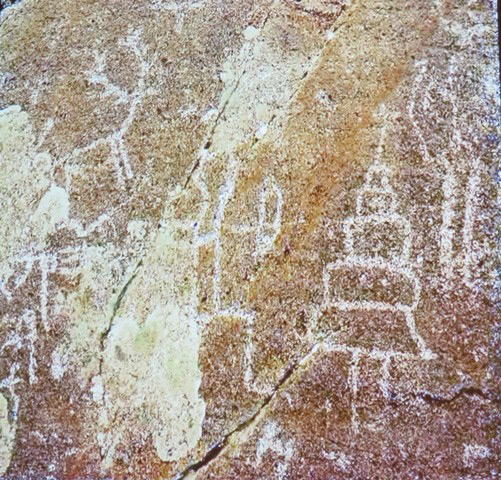

Fig. 119. Figure with a bow and what appears to be a quiver by his side and exposed male genitalia. Rock art from Lhalu Khar (Lha-klu mkhar), Pashoe (Dpa’-shod) county, eastern Tibet. Probably late Protohistoric period. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 120. Various figures including a bowman, stag, and tiered shrine. Rock art from Lhalu Khar, Pashoe county, eastern Tibet. Probably late Protohistoric period. Tibet Museum collection.

The ceremonial monument depicted in this rock art is of a type that spread all the way to Western Tibet, and beyond to Ladakh, northern Pakistan and the Wakhan corridor. For the rock art in figs. 119 and 120, also see Suolang Wangdui’s (bSod-nams dBang-’dus) 1994 book: Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings, “Introduction” by Li Yongxian and Huo Wei, Chengdu: Sichuan People’s Publishing House. Go to pp. 166, 169

Next Month: A plan to conserve the archaeological treasures of Upper Tibet!