June 2017

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another high reaching Flight of the Khyung! We begin this month with a major exhibition of wild yaks in the rock art of Upper Tibet, the final part of a three-part article. The second feature in this newsletter reviews a recent article by Mark Aldenderfer and Jacqueline T. Eng. I use their excellent work as a platform to consider how Old Tibetan literature is relevant to understanding ancient burial sites scattered around the Tibetan Plateau.

Cutting Horns and Thundering Hooves: Wild yak portrayals in the rock art of Upper Tibet – Part 3

For the first two parts of this article, see the April and May 2017 newsletters.

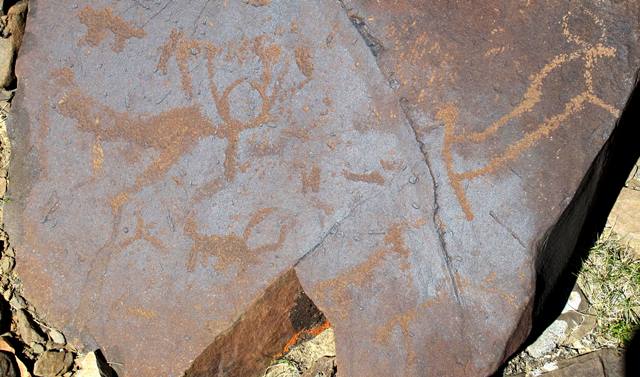

Group 12: Wild yaks with linear tail raised upward

This group of wild yaks is defined by linear tails that point above the level of the back. It is otherwise a fairly diverse group exhibiting various motifs and techniques of production. There are however no specimens with S-shaped backs, a common motif in many other groups of wild yaks. This group appears to date mainly to the Protohistoric period.

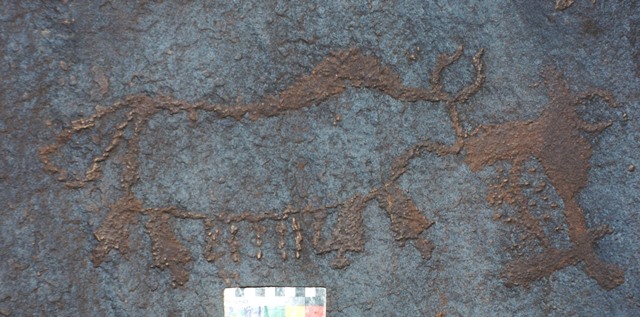

Fig. 163. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: linear tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rectangular snout; rounded belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 164. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: linear tail; thick, inward curving horns; anterior hump; rectangular snout; rounded belly; three unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 165. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long, hooked linear tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rounded snout; flat belly; four long, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 166. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long, hooked linear tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; blunt snout; flat belly; four long, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 167. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: linear tail; circular horns; anterior hump; blunt snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: lightly engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 168. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: hooked linear tail; thick, inward curving horns; anterior hump; rectangular snout; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: lightly engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 169. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: linear tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rectangular snout, head open on top; flat belly; unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 170. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: linear tail; inward curving horns; no hump; rectangular snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: lightly engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 171. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: hooked linear tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rectangular snout; rounded belly; four unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: lightly engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 172. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: linear tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump, long neck; triangular snout; rounded belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, black pigment

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Early Historic period

Group 13: Wild yaks with no discernable tail

This group of wild yaks is defined by the lack of an obvious tail, whether there originally was none or possibly where it has disappeared through damage. This small group is stylistically and technically diverse with no other obvious features that weld its specimens in a single artistic category.

Fig. 173. Lone wild yak, extreme rear missing

Prominent motifs: tail broken; inward curving horns; anterior hump; square snout; rounded belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 174. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: no obvious tail; inward curving horns; no hump; blunt snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 175. Lone wild yak, rear heavily damaged

Prominent motifs: no obvious tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; square snout, gaping mouth; flat belly; unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, black pigment

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period or Early Historic period

Fig. 176. Lone wild yak, rear heavily damaged

Prominent motifs: no obvious tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rectangular snout; rounded belly; unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period or Early Historic period

Fig. 177. Lone wild yak, partially superimposed on black pigment pictograph

Prominent motifs: no obvious tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rounded snout; rounded belly; unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Early Historic period

Group 14: Stick figure bodies and appendages

The four wild yaks of this group are characterized by very thin torsos, although only one of them is a true stick figure. While stick figure animals are common in the rock art of some regions, in Upper Tibet they are very uncommon. Save for the shape of the torsos, the members of this group share very little in common.

Fig. 178. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; V-shaped horns with flared ends; S-shaped back; triangular snout; rounded belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 179. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: upward pointing ball-shaped tail; circle horns; no hump; blunt snout; rounded belly; two flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 180. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rounded snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: lightly engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 181. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: no obvious tail; inward curving horns; no hump; square snout; flat belly; three, long unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Group 0: Wild yaks with idiosyncratic combinations of motifs0

This is a group of miscellaneous wild yak figures, exhibiting unusual motifs and various methods of production. Spanning much of Upper Tibet, the members of this group date mostly to the Iron Age.

Fig. 182. Wild yak with other animals in close proximity (not illustrated) produced using same technique

Prominent motifs: no obvious tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rounded snout; rounded belly, hairy fringe; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined with markings

Technique: engraved in soft substrate

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Fig. 183. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: snub tail; long, diverging sinuous horns; small anterior hump; rounded snout, long neck; rounded belly; four flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 184. Two-headed wild yak

Prominent motifs: no tail; long, inward curving horns; two small anterior humps; square snout; rounded belly; one flexed leg/one unflexed leg

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Note: Not clear if this is a mythological representation or a naturalistic scene depicted from an unusual perspective

Fig. 185. Lone wild yak, horns damaged

Prominent motifs: snub tail; horns; no anterior hump; triangular snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 186. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: stick tail; V-shaped horns; small anterior hump; rounded snout; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 187. Unfinished wild yak

Prominent motifs: no tail; no head; anterior hump; flat belly; one partial leg

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Group 16: Wild yaks with bi-triangular bodies

This group of just three pictographs is defined by the technique used to create them, as well as their bi-triangular body shape. In some Inner Asian regions, bi-triangular animal forms are quite common but this is not the case in Upper Tibet. The figures in this group were presumably produced by using a piece of the mineral colorant as a kind of crayon. Dating to more recent times, these rudimentary pictographs represent an decadent extension of the old rock art making tradition of Upper Tibet. All three are found in the Eastern Changthang.

Fig. 188. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; short horns; rounded snout; arched belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted, bi-triangular

Technique: painted, black pigment

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Vestigial period or later

Fig. 189. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: downward pointing, long stick tail; short horn; triangular snout; arched belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted, bi-triangular

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Vestigial period or later

Fig. 190. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; circular horns; blunt snout; arched belly; two unflexed rear legs

Body: silhouetted, bi-triangular

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Vestigial period or later

Group 17: Wild yaks drawn with a piece of red ochre used like a crayon

The two yaks of this group were made in recent centuries, and it is not clear whether the wild or domestic form of the animal is being depicted. These yaks were drawn in a rudimentary manner using a chunk of red ochre as a kind of crayon. The crude drafting of the yaks has resulted in animals with stiff and naïve lineaments.

Fig. 191. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; rounded snout; arched belly with long fringe; long, unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Postdating Vestigial period

Fig. 192. Lone wild yak, rear portion damaged

Prominent motifs: inward curving horns; triangular snout; rounded belly; long, pyramidal front leg

Body: outlined

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Postdating Vestigial period

Group 18: Pairs of wild yaks, each exhibiting various defining motifs and styles

This group of wild yaks portrays those in pairs, comprising both separate and integral compositions. These pairs of wild yaks are presented in relation to one another in a variety of configurations including head to head, facing in opposite directions, at right angles to one another, back to back, and on top of one another. This is a highly diverse group stylistically and chronologically.

Fig. 193. Two wild yaks that may form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward/downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns with/without flaring tips; S-shaped back/anterior hump; triangular/rectangular snout; rounded/flat belly with fringe; four/two unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 194. Two wild yaks

Prominent motifs: upward pointing wedge-shaped/upward pointing ball-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; square/rectangular snout; rounded/arched belly; four/two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted; outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age/Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 195. Two wild yaks

Prominent motifs: downward/upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rounded/square snout; rounded belly with fringe; four unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted/silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 196. Two wild yaks

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped/stick tail; inward curving/inward curving with right angle horns; anterior/no hump; rounded/square snout; flat belly; four flexed/two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted/stick

Technique: deeply/lightly engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age/Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 197. Two confronted wild yaks that appear to form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward/downward pointing ball-shaped tail; forked/inward curving horns; S-shaped back; square/rectangular snout; rounded belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 198. Two wild yaks that may possibly form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward pointing ball-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; square/triangular snout; rounded belly; four/two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 199. Two wild yaks that appear to form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: downward/upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rounded/blunt snout; flat/rounded belly; two flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 200. Two wild yaks

Prominent motifs: downward/upward pointing ball-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; triangular snout; rounded/flat belly; two unflexed legs

Body: outlined/silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

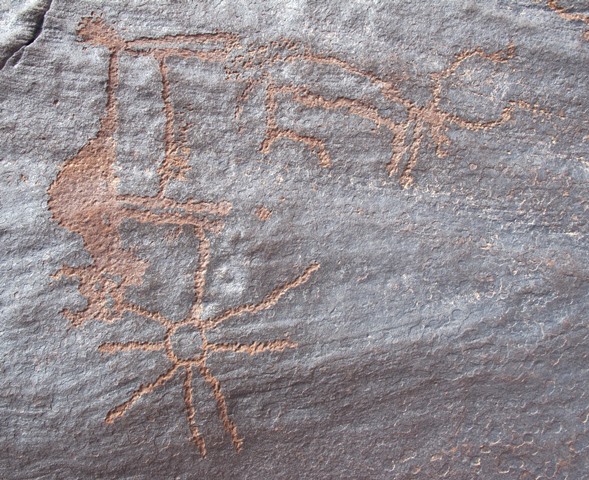

Fig. 201. Two wild yaks and sun with eight rays that appear to form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward/downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving/double curved horns; anterior/no hump; rounded/wedge-shaped snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted/outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 202. Two wild yaks facing in opposite directions that may form integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward pointing ball-shaped tail; inward curving horns, right specimen: head open on top; anterior hump; triangular snout, long neck; arched/rounded belly; pyramidal front legs, two unflexed rear legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 203. Two wild yaks

Prominent motifs: no visible/upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; blunt/square snout; flat belly; two/four unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted/silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 204. Two wild yaks and another animal that appear to form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; square snout; rounded/flat belly; two unflexed legs

Body: outlined/silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 205. Two wild yaks with another animal in between

Prominent motifs: upward pointing wedge-shaped/stub tail; inward curving/circular horns; S-shaped back/anterior hump; rectangular snout; rounded belly; four/two unflexed legs

Body: outlined/silhouetted

Technique: deeply/moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 206. Two wild yaks that appear to form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; forked/inward curving horns; S-shaped back/anterior hump; triangular/square snout; flat belly; two/four unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted/silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 207. Wild yak with what seems to be a calf about to take milk that appear to form an integral composition, three other wild ungulates to the left

Prominent motifs: downward pointing stick tail; inward curving horns; no anterior hump; triangular snout; rounded belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Note: Scene situated immediately to right of fig. 228

Fig. 208. Wild yak and another wild ungulate

Prominent motifs: downward pointing stick tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; blunt snout; flat belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 209. Two wild yaks that may form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward/downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; circular/inward curving horns; anterior hump; rectangular snout; flat/rounded belly; two/four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 210. Two wild yaks (right side) and other figures

Prominent motifs: downward/upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rectangular/rounded snout; arched/rounded belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 211. Two wild yaks that may possibly form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; rounded snout; rounded belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: lightly engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 212. Two wild yaks back to back that appear to form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: long, downward/upward pointing stick tail; inward curving horns; small anterior hump; rounded snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 213. Two confronted wild yaks that form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward pointing ball-shaped tail; circular horns; small anterior hump; rectangular/rounded snout; flat belly; four flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 214. Two wild yaks

Prominent motifs: downward/upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; small anterior hump; triangular/square snout; rounded/flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 215. Two wild yaks

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; no/small anterior hump; blunt/rounded snout; flat/rounded belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: lightly/moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 216. Two wild yaks

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped/upward pointing stick tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; triangular/square snout; flat belly; two unflexed legs

Body: outlined, one specimen: inner body contour

Technique: lightly/moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 217. Two wild yaks that appear to form an integral composition and counterclockwise swastikas

Prominent motifs: upward/downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; double curved curving horns; anterior hump; rounded/square snout; flat belly; four thick, unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Note: These are unusually large petroglyphs (145 cm and 160 cm in length).

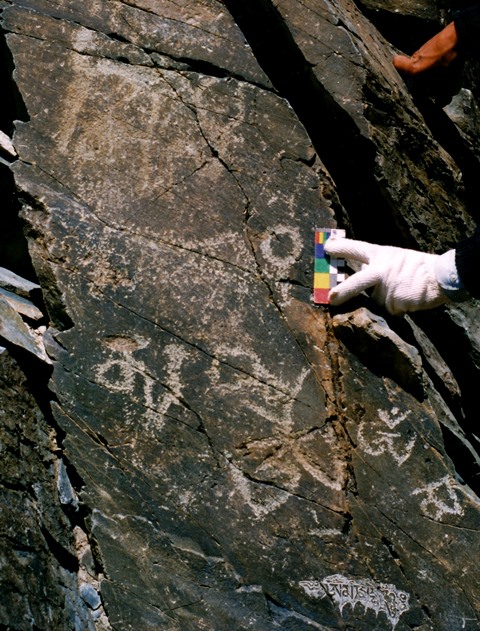

Fig. 218. Two wild yaks and Tibetan letters (ma, ?, Om, Om, ma)

Prominent motifs: upward pointing ball-shaped/downward pointing stick tail; inward curving/circular horns; anterior hump; square/triangular snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately/lightly engraved, upper specimen: retouched

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period/Early Historic period

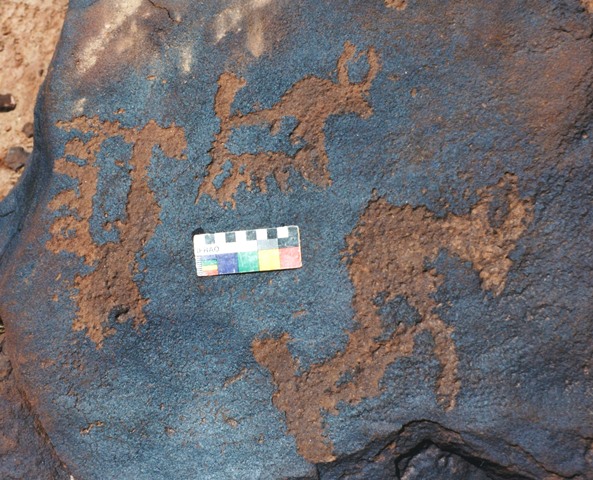

Group 19: Mating wild yak pairs

This small group of wild yaks is made up of pairs shown in a mating aspect. The group is quite closely related in terms of style, location and chronology.

Fig. 219. Mating wild yaks

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior/no hump; rectangular snout; rounded/flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted/partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 220. Mating wild yaks

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; triangular snout; rounded/flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted/partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 221. Mating wild yaks

Prominent motifs: downward/upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rounded/rectangular snout; rounded/flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted/partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Group 20: Multiple wild yaks exhibiting various defining motifs and styles

This group of wild yaks is marked by compositions contains multiple specimens, as well as other animal subjects in some cases. The group does not possess defining stylistic or chronological features.

Fig. 222. Three wild yaks and other figures

Prominent motifs: upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; elongated/triangular/rectangular snout; rounded belly; two/four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted/outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age/Protohistoric period

Fig. 223. Four or five wild yaks and other figures

Prominent motifs: downward/upward pointing wedge-shaped/no tail; no/inward curving horns; S-shaped back/anterior hump; no/blunt/rounded snout; rounded/flat belly; two unflexed/four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted/outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 224. Three wild yaks and circle

Prominent motifs: upward pointing wedge-shaped/not visible tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back/anterior hump; wedge-shaped/square snout; rounded/flat belly; two/four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 225. Three wild yaks possibly forming an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; one horn/inward curving horns; anterior hump/ S-shaped back; square/triangular snout; flat belly with hairy fringe/rounded belly; four/two unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 226. Two or three wild yaks possibly forming an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward pointing ball-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rounded/square snout; arched/flat belly; two/four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted/partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 227. Four or more wild yaks and other figures, some of which possibly form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped/upward pointing ball-shaped tail; inward curving horns; no/anterior hump/S-shaped back; triangular/square snout; flat/rounded belly; two/four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 228. Two or more wild yaks and other wild ungulates including a stag, some of which possibly form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; triangular snout; arched/rounded belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 229. Two or more wild yaks and other wild ungulates, some of which possibly form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: downward pointing stick tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back/anterior hump; square snout; rounded/flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: lightly engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 230. Three wild yaks and curvilinear motif that may possibly form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: upward/downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; triangular snout; rounded belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 231. Seven wild yaks (two partially visible), some of which may possibly form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: downward pointing wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; triangular/rounded snout; flat/rounded belly, with/without hairy fringe; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

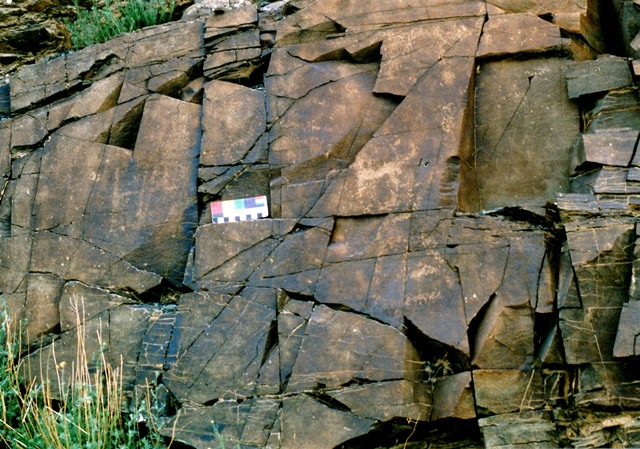

Fig. 232. Two or more wild yaks, other wild ungulates and counterclockwise swastika, some of which may possibly form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: downward pointing ball-shaped/no tail; circular/forked horns; anterior hump; rounded snout; rounded belly; four flexed/unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Note: This rock art and much of the rest of this extensive site (known as Rno-ba g.yang-rdo [sp.?]) was destroyed several years ago by the construction of a dam.

The Ancient Burials of Mustang: A review of a recent article by Mark Aldenderfer and Jacqueline T. Eng

This article reviews the following work: Mark Aldenderfer and Jacqueline T. Eng. 2016: “Death and Burial among Two Ancient High‐Altitude Communities of Nepal”, in A Companion to South Asia in the Past (eds. G. Robbins Schug and S. R. Walimbe), pp. 374–397. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.*

Also see review of article on the human genome of early Mustang (Aldenderfer is a contributing author) in last month’s Flight of the Khyung.

Authors’ findings

The Aldenderfer and Eng article describes two burial sites in Mustang, a Transhimalayan region in west-central Nepal. These two sites named Mebrak and Samdzong date to late prehistoric and early historic times, 2400 to 1200 years ago. The authors’ work is primarily devoted to an osteological investigation of human remains collected at these sites.

Based on data from historical and anthropological studies focused on more recent times, the authors argue that the population of ancient Mustang was affected similarly by small-scale migrations due to changes in the subsistence economy, large-scale migrations associated with climate change and political upheavals, the development of extensive trade networks, and regional wars.

Aldenderfer and Eng introduce the major findings of two Nepali-German archaeological teams that explored Muktinath valley, most notably a burial cave at Mebrak (Me-brag?), in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The work of these international scholars was detailed in a series of articles including Alt et al. 2003; Huttel, 1993; Knorzer, 2000; Schon and Simons 2001; Simons and Schon, 1998; Simons et al., 1994a; 1994b; 1998 (see Aldenderfer and Eng for bibliographic details). The human and animal remains and artifacts recovered by the Nepali-German teams languished for nearly two decades until again coming under scientific scrutiny. In this regard, the perseverance shown by Mark Aldenderfer in gaining access to this collection of critical materials is particularly noteworthy.

The burial cave at Mebrak known as Mebrak 63 (measures 2 m x 3 m) is situated in a conglomerate formation 30 m above ground level. The Nepali-German archaeological teams discovered well preserved leather and fur clothing, wooden and bamboo objects, ceramics, and metallic items inside the cave. The radiocarbon analysis of bone, rice fragments, soot, bamboo, and wood from Mebrak 63 yielded calibrated dates ranging from 400 BCE to 50 CE. Human skeletal remains in the cave had been disarticulated and heavily disturbed, obscuring the relative status and ritual dispensation of the individuals interred. Three wooden bier-like platforms with ornate carvings and paintings of red deer and blue sheep were installed in the cave. The skulls of caprids and an almost complete horse skeleton lay on the floor of the burial chamber.* It is thought by Aldenderfer and Eng that Mebrak 63 probably catered to the needs of the nearby settlement of Phudzeling (Phun-tshogs-gling).

According to Aldenderfer, animal remains first appear in the tombs of Upper Mustang in the Mebrak period, but become more common during the Samdzong phase of occupation. See Mark Aldenderfer. 2013: “Variation in mortuary practice on the early Tibetan plateau and the high Himalayas”, in Journal of the International Association for Bon Research (ed. J.F. Marc des Jardins), vol. 1, pp. 293–318. This article presents a summary of Tibetan mortuary practices derived from accounts of the many hundreds of tombs excavated by the Chinese since the 1980s (after Chayet 1994; Huo Wei 1995). These tombs are believed to date from the Late Neolithic to the end of the Imperial period (mid-9th century CE).

Evidence for the next phase of occupation in Mustang comes from Samdzong (Bsam-rdzong), a communal burial site situated northeast of the capital of the region, Lo Manthang. In 2009, an earthquake exposed the tombs and caused much damage to the structures and their contents. In 2010, the authors and their team discovered ten shaft tombs at Samdzong, bringing to light a wide spectrum of human, animal and material traces. All but one of these tombs was communal in nature, containing in total at least 105 individuals (eighty-three of them were buried in one tomb alone: Samdzong 1). Like Mebrak, the dead were interred at Samdzong over an extended period, necessitating the periodic rearrangement of human remains to accommodate new burials. Among the finds were wooden and bamboo objects, metal implements and household goods (vessels, knives, daggers, plates, arrowheads, and horse tack consisting of buckles and rings), leather straps, broken ceramics, small fragments of copper, bark container, wooden objects, a few stone and glass beads, and textile remnants. Additionally, two anthropomorphic masks made of gold and silver crumpled into small lumps were collected. The remains of caprids, bovids and equids were also found in the tombs of Samdzong. Most commonly, sheep and goat bones were deposited in the burials, but also those of horses and yaks. The results of nine radiocarbon assays indicate that the interments were made between 400 and 825 CE. None of the shaft tombs were fully intact but Aldenderfer and Eng estimate that the opening passages were 2 m to 6 m in length and the tomb chambers 6 m² to 21 m².

In burial Samdzong 5, an intact square coffin with a horse rider painted on one side contained the incomplete remains of an adult male, as well as copper vessels, wooden and bamboo containers and cups, iron daggers, silk of Chinese origin, iron tripod, and glass beads from Sassanid Iran, the southern Subcontinent, and possibly Central Asia. Aldenderfer and Eng discovered another gold and silver burial mask in Samdzong 5.

Utilizing established scientific protocols, Aldenderfer and Eng undertook a painstaking analysis of human osteological materials recovered from Samdzong. This permitted them to determine the minimum number of individuals represented, as well as partially gauging their age, sex, perimortem injuries, nutritional status, and prevalence of dental disease.

In some cases, skull fractures point to interpersonal violence and homicide. An iron arrow point was found embedded in the ankle bone of an adult male that exhibited no sign of healing, suggesting that death of this individual occurred shortly thereafter. On the other hand, bone fractures in some individuals showed signs of healing. Around one-fifth of the total number of discrete human bones collected at Samdzong had deliberate cut marks on them indicative of a defleshing practice. The patterning and location of these cut marks reveal the existence of a highly systematic activity associated with a well established mortuary tradition. No differences in the frequency of cut marks were observed in the age and sex profile of those buried. Aldenderfer and Eng consider whether these secondary burials were associated with Zoroastrian customs or developed out of local traditions. They also note that the burials at Mebrak and Samdzong have strong affinities with so-called shaft burials at Gurgyam, in southwestern Tibet. In summary, the authors note that the burials of Mustang reveal an exchange network reaching from China to Sassania. The gold and silver masks link the region to Xinjiang and Kyrgyzstan, territories that also have golden burial masks (see November and December 2013 Flight of the Khyung). Finally, the authors review the funerary evidence and whether it might be indicative of deviant burials (types that differ from customary burials of the same group and period), reaching no clear conclusion.

In the conclusion to their article, Aldenderfer and Eng announce the discovery of a burial complex set in a fissure in a cliff near the town of Manang. Although this site (called Kyang) it is said to be contemporaneous with Mebrak to the west, the mortuary structures and artistic motifs in the cliff burial vary significantly.

My comments

The ongoing efforts of Mark Aldenderfer in collaboration with various specialists to better understand the cultural and temporal characteristics of pre-Buddhist Mustang have built substantially upon work conducted some two decades ago by Nepali-German archaeological teams. We can expect more such high-quality studies covering a range of archaeological investigations by Aldenderfer, Eng and others.

The working hypothesis of Aldenderfer and Eng articulated at the beginning of their article is that more recent historical events and processes can be used to understand the prehistoric population history of Mustang. However, the analysis of human, animal and artifactual remains from burial sites in Mustang described in their article is not harnessed to test that hypothesis. In fact, the authors’ working hypothesis is not visited again in their article. Nevertheless, maintaining that disparate factors influenced the population history of Mustang in antiquity is a reasonable assumption, but one that should be patently tested by the authors.*

For further information on the health, diet and mechanisms of biocultural adaptation in the ancient population of Mustang, see: Jacqueline T. Eng and Mark Aldenderfer. 2017: “Bioarchaeological profile of stress and dental disease among ancient high altitude Himalayan communities of Nepal”, in American Journal of Human Biology, 20 pp.

Modern archaeological techniques and analyses brought to bear on Mustang will continue to enhance our understanding of the perimortem circumstances of tomb occupants, their demographic and medical status, and the scope of material cultural practices. The information thus obtained can serve as a basis for reconstructing the social, economic and political environment surrounding the burials. However, interpreting the symbolic and ideological significance of the Mustang burials is a more daunting prospect. Unless the material record is supplemented by other sources of information, questions concerning meaning, worth, perception and other abstract values are difficult to address.

Fortunately, the comparative study of Tibetan funerary texts can aid in the elucidation of concepts, practices and objects associated with ancient burials on the Tibetan Plateau. We are particularly concerned here with an analysis of manuscripts from the Dunhuang and Gathang Bumpa collections composed in the Old Tibetan language.* Hypotheses about the significance of burial practices, structures and objects drawn from Dunhuang and Gathang Bumpa texts have the advantage of being grounded in the cultural and historical milieu of Tibet. This non-Buddhist funerary literature was first set down in the Early Historic period (650–1000 CE), but it regularly affirms roots in an earlier (prehistoric) era. Old Tibetan texts were expressly employed to aid Tibetans at the time of death and burial. Burial and tomb construction still dominated cultural practice and landscape modification in the Early Historic period, making textual accounts of that time contemporaneous witnesses or agents to certain mortuary activities. Examining Tibetan mortuary contexts in the light of textual accounts supplies a rich array of myths, beliefs, customs, and rituals helpful in building an interpretive framework.

Some ritual texts composed in the Classical Tibetan language also contain archaic materials of relevance to the mortuary archaeology of the Tibetan Plateau. This is especially true of funerary texts of the Yungdrung Bon religion such as the Mu-cho’i khrom-’dur collection. However, unlike Old Tibetan mytho-ritual texts, Classical Tibetan versions belong to the corpus of still prevailing forms of Tibetan religion. Most Classical Tibetan texts featuring early myths and rituals were as a matter of course reframed as Lamaist documents, characterized by a process of expurgation, interpolation and reinterpretation.

To determine how Tibetan literature is applicable to the mortuary archaeological record it is first necessary to delineate the limitations of an interpretive methodology. Great regional and chronological variations in Tibetan burial practices and structures, combined with ambiguities of function and chronology in Old Tibetan funerary literature, impair comparative avenues of understanding. The degree of correspondence between the archaeological and textual records, disparate sources of data, remains an open question. Most texts contain myths, rituals, personalities, and objects with little or no direct reference to the mortuary regimen underlying them (corpse preparation, tomb construction, grave furniture, deposition of corpses and goods, social participation, etc.). This has the effect of obscuring the precise modes of burial intended by the written record. It is not plain to see which types of tombs and other funerary structures detected in the archaeological record are reflective of ideological and material elements of rituals described in Tibetan literature. Hence, assignments of meaning, worth, perception and other abstract values derived from a system of analysis based on texts remain hypothetical.

It must be stressed that Tibetan texts and mortuary resources do not represent a single cultural idiom. Although regional proclivities and environmental adaptations are also involved, some variations in the mortuary record spring from cultural factors. Archaeological surveys of the monumental remains demonstrate that mortuary patterns on the Tibetan Plateau differed considerably from region to region, betokening significant cultural variability (also attested in the Tibetan historical tradition, rock art record and linguistic map of the Plateau).* As documented by Aldenderfer and Eng, even fringe areas of the Tibetan Plateau separated by less than 100 km, Mustang and Manang, differ significantly in the manner of burial and ritual procedure. Set down in the Early Historic period, Tibetan funerary texts also intimate pre-existing cultural variations on the Tibetan Plateau, material, ethnic and ideological distinctions that were effaced, reduced or otherwise submerged with its imperial unification.

For example, the concourses of pillars appended to temple-tombs and walled-in funerary pillars of Upper Tibet are entirely absent from Central Tibet. On variability in the Tibetan mortuary record, see:

Aldenderfer 2013 (bibliography above)

Bellezza, John V. 2014: Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: A Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites on the Tibetan Upland, Ceremonial Monuments, vol. 2. Miscellaneous Series – 29. Sarnath: Central University of Tibetan Studies. Online version, 2011: Tibetan & Himalayan Library (THlib.org): http://www.thlib.org/bellezza.

Chayet, Anne. 1994. Art et Archéologie du Tibet. Paris: Picard.

Huo Wei. 1995. Xizang Gudai Muzang Zhiduyanjiu. (Studies on Ancient Tibetan Burial). Chengdu: Sichuan People’s Publishing House.

Most mythic tales of origins appended to Old Tibetan funerary rituals attribute this complex tradition to ‘ancient’ or ‘primal’ times. Many ancestral personalities (aristocrats and their families, priests, victims, etc.) are noted in these myths. Historicizing this material, however, poses substantial challenges, foremost of which is the essentially ahistorical slant of the tales of origins. The mythic narratives are mutable, symbolic, metaphorical, and magical in character, not prosaic chronicles of past events. Affirmations of antiquity made in the funerary texts are motivated primarily by the need to legitimize the ritual dispensation and confer prestige and authority upon it. Historical signposts (biographical, political, climatic, geological) that might be used to gauge the age of funerary myths are conspicuously lacking in Old Tibetan literature. Although technological information related to ritual praxis (eg., equestrian arts, metallurgy, architecture, material goods) provide some clue as to the maximum possible antiquity of events described in the myths, it does not chronologize them with any precision.

Obstacles to textual methods of analysis of the Tibetan archaeological record outlined above pose formidable challenges to applying specific literary references to specific mortuary contexts. Thus, comparisons are best carried out in a minimally restrictive manner, reducing the risk of mismatching Tibetan texts with mortuary data.

Fortunately, the geographic scope of non-Buddhist funerary accounts is often detailed in their contents, in which numerous toponyms are mentioned. Where identification of place names is feasible, most early funerary manuscripts are set in Upper Tibet and Central Tibet, a swathe of territory extending from Gu-ge and the headwaters of the four great rivers in southwestern Tibet almost to the great bend in the Brahmaputra river in the east. One thousand five hundred km in breadth, this region constitutes the core cultural zone of Old Tibetan mytho-ritual literature.

Cultural-historical and archaeological evidence indicates that there was a good deal of continuity in Tibetan cultural expression between prehistoric and protohistoric times and the Early Historic period. Specific types of evidence from the mortuary record given below substantiate this view, pointing to a cultural heritage highlighted in Old Tibetan funerary manuscripts of considerable historical depth.* Human genomic studies establish that there was no major demic replacement of the Tibetan population in the last several thousand years (see March and May 2017 Flight of the Khyung). It appears therefore that a relatively stable population history underpins Tibetan cultural continuity. Furthermore, linguistic evidence from Old Tibetan texts must also be considered. The grammatical structure and literary quality of this language is highly sophisticated, the product of centuries of evolution. Thus, it can be assumed that certain fundamental eschatological concepts, mythic motifs and ritual constructs found in the Old Tibetan funerary myths were not entirely the result of cultural innovation in the Early Historic period. Rather, certain seminal themes seem to have stemmed from antecedent Tibetan intellectual and technological legacies, as affirmations of antiquity in funerary myths of origins suggest.

This theme of cultural perdurability is elaborated upon in my books (Zhang Zhung [2008], Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet [2013], The Dawn of Tibet [2014]) and in various articles in Flight of the Khyung.

It appears that Old Tibetan funerary texts were imbued with a fund of temporally persistent and geographically pervasive conceptual, symbolic and procedural components of the non-Buddhist funerary tradition, those beliefs, myths, customs, and practices that defined the early Tibetan cultural world in broad or overarching terms. These pillars of the funerary tradition form reoccurring idealizations and standardized patterns of exposition in texts, serving as leitmotifs that permeate Old Tibetan funerary literature.*

Specific narrative tropes and ritual actions may also be carryovers of earlier times but probably less so than more encompassing themes. Even details in cognate myths and rituals in non-Buddhist Old Tibetan literature vary considerably, indicating that these were not fixed quantities, but rather the object of amendment and embellishment in the Early Historic period. Variability in cognate mytho-ritual materials may reflect localized output, predilections of authors, or alternative sacerdotal outlooks, etc. The potential for funerary texts composed in Early Historic period to have modified or omitted antecedent traditions (as documented in the archaeological record) is of course far higher still. In fact, forces of cultural change and adaptation could have been so great that the minutiae of stories and liturgies recorded in surviving literature may bear little or no resemblance to prehistoric or protohistoric mortuary conceptions.

Although storyline particulars in Old Tibetan texts may not be reliable indicators of actual mortuary practices on the Tibetan Plateau, the ideas and activities underlying them are worthy of close consideration. It appears that overarching eschatological themes, mythic motifs, and ritual constructs constituting leitmotifs in non-Buddhist funerary literature comprise an abstract backdrop to the means of burial exhibited by the archaeological record of the Tibetan Plateau (particularly the core cultural zone). It is the leitmotifs, those long-standing and with wide currency, not the idiosyncratic details of mytho-ritual accounts, which are best suited as interpretative instruments for mortuary evidence. In Old Tibetan literature, some leitmotifs are known as dpe and function as prototypes for funerary ritual concepts and activities.* The dpe include archetypal personalities, the original inhabitants of countries and principalities. Some of these personalities were victims of untoward death, others were members of the priesthood who helped them win passage to the otherworld.

There are several dozen such leitmotifs in Old Tibetan funerary texts. For example, those regarding the psychopomp equids (do-ma) can be summarized as follows:

1) These horses were magical vehicles used to deliver the deceased to a celestial afterlife.

2) The funerary transport horses were the favorites of the deceased and made available by relatives and associates as a special conferment.

3) The exposition of the mythic origins (smrang) of the funerary transport horses formed a key part of the burial rites. The ultimate source of these horses was traced back to a primordial or celestial sphere.

4) The funerary rituals connected to the heaven-bound horses were conducted by a special class of priests known as dur-gshen/gshin-gshen, who wore distinctive attire and carried special ritual appliances.

5) The journey between life and death was fraught with perils and was conceived of using geographic metaphors such as sands, rivers and mountains.

6) The erection of bird horns on the head of the horse, the placement of saddles and bridles, and the manipulation of the tails and mane functioned as various kinds of apotropaic objects to eliminate demonic obstacles confronting the deceased en route to the afterlife.

7) The afterlife was primarily conceived of as possessing physical qualities and living conditions like those found on earth.

8) The afterlife was an empyreal realm in which resided the ancestors or manes of the deceased.

The highly variable mortuary record of ancient Tibet suggests that funerary leitmotifs were endowed with appreciable cultural versatility.* These fundamental themes and prototypes may even be trans-cultural in nature, encompassing not only the heartland of Tibet but also peripheral regions of the Tibetan Plateau. A trans-cultural orientation could also explain affinities between the contents of Old Tibetan funerary texts and burial traditions in other parts of Inner Asia.†

Widely occurring funerary leitmotifs in Old Tibetan literature, by bridging significant cultural and regional variability in burial traditions on the Tibetan Plateau, almost certainly had political value during the Imperium (mid-7th to mid-9th centuries CE), serving as an instrument of territorial amalgamation and cultural assimilation. How many of these leitmotifs are authentic cultural anachronisms and how many emerged from the imperial context remains to be determined.

For example, as regards animal remains in the Mustang tombs of Mebrak and Samdzong, Aldenderfer (2013) suggests that they represent funerary customs originating from far to the north or west.

Now that I have reviewed how Old Tibetan literature might be germane to an interpretation of the mortuary archaeological record, let us return to the Mustang burials described by Aldenderfer and Eng, in order to better understand their symbolic and ideological significance. Mustang, especially the upper portion of the district, is culturally, linguistically and geographically an extension of the Stod region of Upper Tibet. It had been closely aligned to adjacent areas of Tibet for centuries. Being related to Upper Tibet, part of the core region of the Old Tibetan funerary tradition, accentuates the utility of comparisons made between the Mustang mortuary record and Tibetan texts. Old Tibetan literature permits Mustang mortuary structures, objects and practices to be seen in terms of a compass of fundamental eschatological concepts, mythic motifs and ritual constructs.

The red deer and blue sheep painted on the wooden platforms in Mebrak 63 can probably be related to beliefs and practices in the Dunhuang and Gathang Bumpa collections revolving around wild and domestic ungulates acting as psychopomps. In Old Tibetan texts, deer and sheep guide and carry souls of the deceased through the postmortem realm (envisioned as full of geographic obstacles) to the afterlife. This kind of leitmotif may also explain the horse rider painted on the wooden coffin discovered in Samdzong 5. If so, this funerary painting was aspirational in nature, a rendition of the journey to the otherworld made by the occupant of the tomb. Moreover, the positioning of the cave and shaft tombs of Mebrak and Samdzong well above ground level and the deployment of wooden burial platforms suggest that the otherworld was conceived of as a high-reaching or heavenly phenomenon. In Old Tibetan literature, the afterlife is celestial in nature and is known by epithets such as ‘Joyous Land’ (Dga’-yul) and ‘Joyous Mountain’ (Dga’-ri).

The horse skeleton and caprid skulls deposited in Mebrak 63 could also be the remains of psychopomps, sacrificed by priests in the service of the deceased (well described in Tibetan funerary literature). Old Tibetan funerary manuscripts also mention the sacrifice of caprids, cervids, equids, and bovids, in order to ransom or purchase the souls of the dead from infernal demons. Furthermore, Tibetan sources list food provisions for the dead for use in the next life, furnishing another possible interpretation for ungulate remains deposited in the tombs of Mustang. The crumpling of the gold and silver burial masks in Samdzong can also be seen through the prism of ancient Tibetan funerary texts. A number of different kinds of ‘faces’ are listed in Old Tibetan and Classical Tibetan accounts including ‘golden visages’ (gser-zhal). These objects were used as receptacles for the soul during evocation rites and dismantled or discarded after the deceased was sent on his or her way to the afterlife.

As more information about ancient burials in Mustang and other regions of the Tibetan Plateau becomes available, Old Tibetan funerary texts promise to play a critical role in ascertaining their possible meaning and significance.

To conclude this review, a word on possible Zoroastrian influences in the Samdzong burials is in order. It must be observed that the mortuary monuments of Upper Mustang and those of Upper Tibet bear little or no resemblance to Achaemenid or Parthian tombs and mausolea. The ancient rock art and portable art of Upper Tibet also contrasts strongly with esthetic traditions of ancient Persia, as do early temples and fortresses in both regions. Although defleshing was common to Persia and Upper Mustang, the mortuary contexts in which it occurs are very different. For these reasons, it is doubtful that there was any direct influence of Zoroastrian mortuary culture on Upper Mustang, or on adjoining parts of the Tibetan Plateau. The dismembering of corpses is described in a Chinese T’ang document (completed in 801 CE) as an idiosyncratic Zhang Zhung mortuary custom.* Moreover, the preparation of corpses through defleshing in Western Tibet is suggested by the design of mountaintop cubic tombs, a common type of pre-Buddhist mortuary structure in that region. These aboveground drystone masonry chests contain a central depository with a capacity of generally 0.28 m³ to 1.4 m³, a space insufficient to accommodate a primary adult burial. Rather, these depositories appear to have contained secondary burials consisting of human skeletal elements, the fragments of which are found in some examples to this day.† (see Bellezza 2014).

See p. 527 (n. 9) of Bushell, Stephen W. 1880. “The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources” in Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 12, pp. 435–541. London.

See Bellezza 2014 (bibliographic reference, supra); pp. 155, 156 of 2001. Antiquities of Northern Tibet: Pre-Buddhist Archaeological Discoveries on the High Plateau, 1999. Delhi: Adroit.

Next Month: Carnivores and their prey in the rock art of Upper Tibet and other fascinating accounts!