June 2016

John Vincent Bellezza

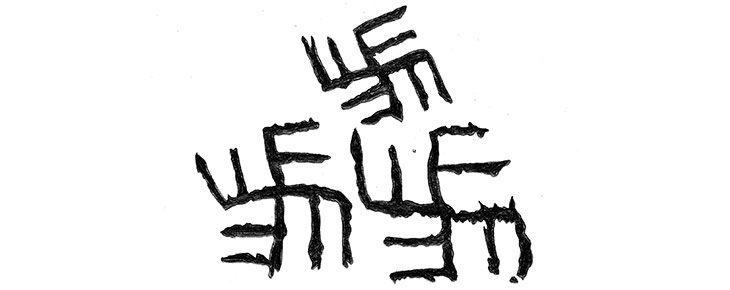

Title Drawing by Rebecca C Bellezza

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung and the tale of the swastika in uppermost Tibet! We explore the central role of this universal symbol in the beliefs, aspirations and struggles of a people occupying one of the largest territories in the heart of Asia. Read on to discover the marvels of Tibet’s most catholic sign from prehistory to the modern age.

A Mirror of Cultural History on the Roof of the World: The swastika in the rock art of Upper Tibet – Part 2

We begin this month’s survey of swastikas in the rock art of Upper Tibet with solitary specimens carved or painted on boulders, rock faces and caves. Devoid of a wider thematic context, the function of this prehistoric symbol is difficult to determine. Isolated swastikas are also harder to date. It is likely that some were solar symbols, markers of hunting grounds for specific bands, or with ritualistic functions in archaic religious traditions.

A kind of archetypal symbol, swastikas dating to the Iron Age (circa 700–100 BCE) and Protohistoric period (ca. 100 BCE to 600 CE) come in a variety of styles. They face in both directions and have regular and irregular symmetries. While Scythic groups from north Inner Asia had a significant impact on the rock art, funerary customs and bronze metallurgy of Upper Tibet in the Iron Age, this region was relatively stable culturally in the Protohistoric period. The swastika persisted in both times though, a token of perdurability in a literal as well as a figurative sense.

Fig. 31. Two primitive swastikas on boulder, western Changthang. Probably Iron Age, as suggested by the general contents of the site.

Fig. 32. Solitary swastika, western Changthang. Found at same site as fig. 31. Probably Iron Age.

Fig. 33. Primitive swastika with each set of legs facing in same direction, western Tibet. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 34. Two swastikas with smaller cruciform subject between them, western Tibet. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 35. Highly re-patinated swastika, central Changthang. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Fig. 36. This style of swastika is distinguished by carved parallel lines, central Changthang. Located at same site as fig. 35. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

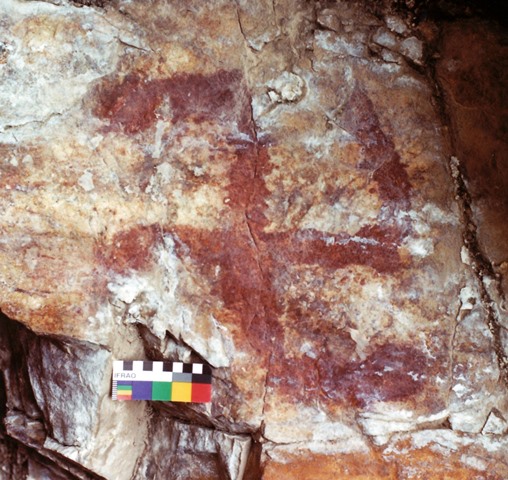

Fig. 37. Red ochre counterclockwise swastika, eastern Changthang. This specimen was painted in a cave that came to be associated with Tibet’s greatest Buddhist missionary, Guru Rinpoche. This swastika is assignable to either the Protohistoric period or Early Historic period.

In the absence of other rock art and Tibetan language inscriptions, it is not clear which pictographic swastikas scattered around the eastern Changthang are actually of prehistoric antiquity. Nonetheless, as with petroglyphic examples we can assume that some predate the Tibetan historical epoch.

The dawn of Tibet’s historical epoch in the 7th century CE is marked by the invention of the Tibetan script and the remarkable expansion of a literary culture on the Plateau. The introduction of literacy in Tibet went hand in hand with the spread of Buddhism, a highly sophisticated religion that relied heavily upon the written word to transmit its teachings and practices.

As I show in an extensive article on stepped shrines in the rock art of Upper Tibet, literacy came slowly to the region.* Preliterate traditions, some extensions of archaic religious traditions, others informed by the advance of Buddhism, seem to have dominated the religious-scape of Upper Tibet from the 7th to 10th centuries CE. This is indicated by the small number of Tibetan inscriptions discovered in Upper Tibet assignable to the Early Historic period. It appears that most pastoral and hunting groups on the Changthang adhered to timeworn religious customs and traditions, which did not require reading and writing. Even in lower elevation agrarian areas of far western Tibet, relatively few epigraphic records predating the 10th century CE have been discovered and most of what has been found is non-Buddhist in nature.

Forthcoming: “A Comprehensive Survey of Stepped Shrines in the Rock Art of Upper Tibet: With archaeological, cultural and historical comments”, written for the International Association of Tibetan Studies, Conference XIV (2016), Bergen. This article contains a 27,000-word text, two maps, 250 black and white typological drawings and some color photographs.

For herders, hunters and farmers in Upper Tibet of the Early Historic period, the swastika remained a seminal symbol and emblem. However, its functional associations gradually evolved to assume new ideological and sectarian dimensions. The most widely circulated swastika in the Early Historic period was oriented anticlockwise. To this day in the Tibetan world, the counterclockwise swastika characterizes non-Buddhist religious traditions.

As we saw in the first part of this article, Buddhists in Tibet have used the swastika as a doctrinal and mystical symbol since the Early Historic period. The Buddhist swastika, however, almost always faces in a clockwise direction. It appears therefore that the counterclockwise variety was propagated in contradistinction to Buddhism. This heralds the start of a sectarianism in Tibet graphically displayed in the orientation of swastikas. Swastikas carved and painted indiscriminately in either direction, the norm in the prehistoric epoch (although counterclockwise ones were most common), acquired directional connotations in the Early Historic period. The counterclockwise swastika as a key non-Buddhist religious symbol is extensively treated in the scriptures of Yungdrung Bon.

Although Yungdrung Bon coalesced in the 11th century CE, antecedents of this religion can be traced to the Early Historic period. In Old Tibetan literature of that period many non-Buddhist mytho-ritual traditions are referred to as bon and their practitioners as bonpo. As with symbology in the rock art of Upper Tibet, these textual traditions informed the development of the Yungdrung Bon religion. In Upper Tibet, local groups propagated a variety of cult traditions, contributing to its formation. However, as the rock art record makes clear, these cults traditions were precursory in nature and in many respects different from Yungdrung Bon, a faith strongly influenced by Buddhist tenets.

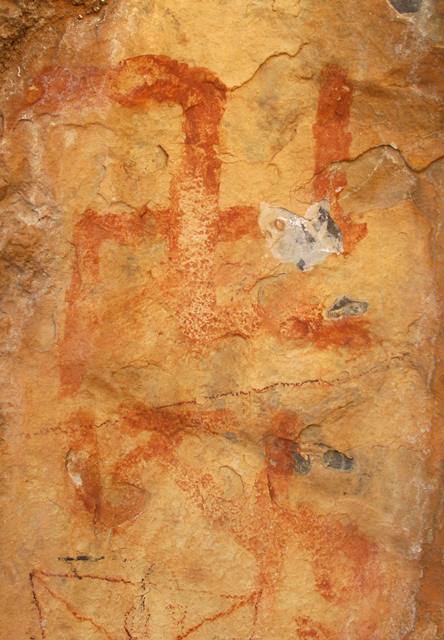

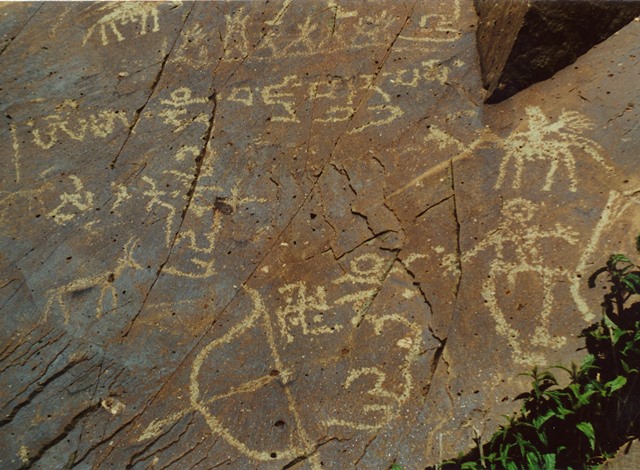

Fig. 38. We begin this exploration of the swastika in the Early Historic period with a spectacular pictograph of a non-Buddhist or bon adept or priest, central Byang thang.

The long fangs, prominent crown or topknot, cat-like pupils and flexed arms and legs portray a powerful individual. The headgear or topknot (gtor gtsug) may possibly have been inspired by Buddhist iconographic traditions. This large figure does not appear to be wearing clothing, another suggestion that it demonstrates spiritual and personal prowess. Note the counterclockwise swastika above the left hand of the priestly figure. This swastika seems to have been painted as part of the same composition.

Along with another anthropomorphic figure around two-thirds of life-size, this red ochre pictograph is found inside a large cave sanctuary. This site with its large masonry façade was established by a those practicing the archaic religious customs and traditions of the region. Large pictographs of non-Buddhist religious figures are rare in Upper Tibet. Moreover, they share only limited iconographical affinities with Yungdrung Bon depictions. I have suggested previously that the wrathful figure under examination was made circa 700–1000 CE, in a time coinciding with the abandonment of the cult site. In the late 11th century CE, this part of Upper Tibet came under Buddhist (Rnying ma sect) monastic domination.

In the Early Historic period, the counterclockwise swastika was associated with stepped shrine rock art in Upper Tibet, belonging to non-Buddhists, those whom we might call bonpo. As with the anthropomorphic figure in fig. 38, these portrayals of cosmological models, fundamental doctrines, tabernacles and ritualized venues have limited correspondence to conventional depictions of Yungdrung Bon chortens (stupas). The Yungdrung Bon historical tradition holds that chortens were first erected in Tibet by its founder Tönpa Shenrab (Ston pa gshen rab) thousands of years ago. However, this view is contradicted by rock art and monumental evidence in Upper Tibet, which shows that stepped shrines were evolving in the Early Historic period under both indigenous and Buddhist influences, only assuming their present configuration after 1000 CE. In the Early Historic period, non-Buddhists in Upper Tibet created many varieties not seen in the Yungdrung Bon tradition.

Fig. 39. Red ochre shrine with wide base, narrow stem, rounded vase, wide entablature, and tricuspidate finial, accompanied by five-pointed star and counterclockwise swastika, eastern Changthang, Early Historic period.

Fig. 40. Two rudimentary shrines, each with a counterclockwise swastika, eastern Changthang. Early Historic period.

Fig. 41. Large pictograph depicting unusually designed shrine and counterclockwise swastika, eastern Changthang. Early Historic period.

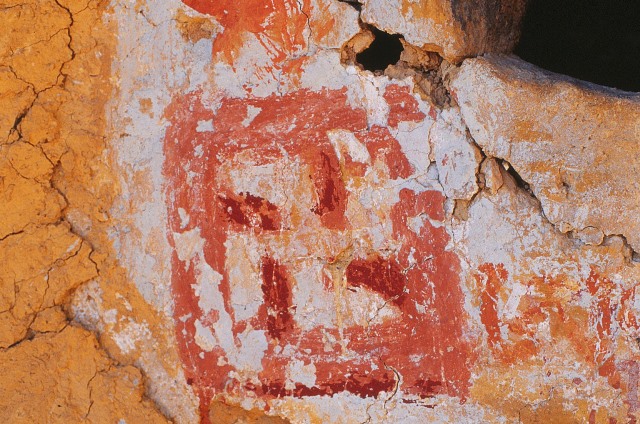

Fig. 42. Polychrome stepped shrine and counterclockwise swastika, central Changthang. This example is more in keeping with the iconometric conventions of chortens in later times.

Fig. 43. Twin stepped shrines and counterclockwise swastika, central Changthang. Early Historic period. These pictographs are found in the same cave sanctuary as fig. 38.

Fig. 44. Elaborate stepped shrine with counterclockwise swastikas in and around it, eastern Changthang. This Early-Historic-period example is a historical predecessor of later Yungdrung Bon variants. Of special note, is the horn-like finial with a rounded prong in the middle, which recalls the ‘horns of the bird, sword of the bird’ (bya ru bya gri) crown (tog) of Yungdrung Bon. The short inscription above the stepped shrine is not legible.

Fig. 45. Another elaborate stepped shrine, eastern Changthang. Early Historic period. The finial and pyramidal spire are major design elements retained in Yungdrung Bon chorten art. Note the interconnected swastikas in the base of the pictograph. Rows of miniature stepped shrines ornament the rounded vase or middle section of the pictograph, an artistic trait also seen in Buddhist rock art chortens in western Tibet and Spiti, circa 1000–1200 CE (see July 2014 and November 2015 Flight of the Khyung).

Fig. 46. Polychrome depiction of the flaming jewels (nor bu me ’bar), three counterclockwise swastikas and the mystic letter A (lowermost pigment application), eastern Changthang. Painted circa 700 to 1200 CE. Polychrome pictographs are uncommon in Upper Tibet. The blue-gray background is particularly rare.

As with chortens, flaming jewels were commonly made as defining symbols and instruments by Tibetan Buddhists. In Buddhism, the flaming jewels primarily represent the tripartite objects of refuge. The adoption of both the chorten and flaming jewels (among other symbols) by non-Buddhists or bonpo in Upper Tibet illustrates an active borrowing from their religious neighbors in the Early Historic period. These were applied to their own shifting religious identity. In that period, Buddhism was in the ascendancy in most parts of Tibet. In the late 8th century CE, King Trisong Deutsen (Khri srong lde’u btsan) is recorded as abolishing bon, but this ban does not seem to have had a big impact on Upper Tibet.

The counterclockwise swastika was also paired with inscriptions, most of which are very short and comprised of a mystic syllable or mantra. Like stepped shrines and flaming jewels, these inscriptions were demonstrations of non-Buddhist religious activities and ideologies, those being shaped to some degree or another by Buddhist intellectual and devotional traditions. The adoption of writing in Upper Tibet beginning in the Early Historic period would have profound implications for the religious evolution of the region. Between 1000 and 1250 CE, remaining non-Buddhist cult groups in the region disbanded as their followers converted to Buddhism.

Fig. 47. Counterclockwise swastika and an inscription that appears to read: sa, western Tibet. Early Historic period. Perhaps these carvings were territorial markers of religious affiliation. The swastika and inscription were not necessarily produced together.

Fig. 48. Pictographic shrine, swastikas and star of same kind as fig. 39, eastern Changthang. Early Historic period. Above the pictographs illustrated is one or two short inscriptions, together reading A hung (second syllable with both consonants and vowel sign fully written out). These two syllables were inscribed in a similar red ochre pigment and exhibit wear characteristics comparable to the shrine, swastika and star, indicating that they were all made in the same time frame.

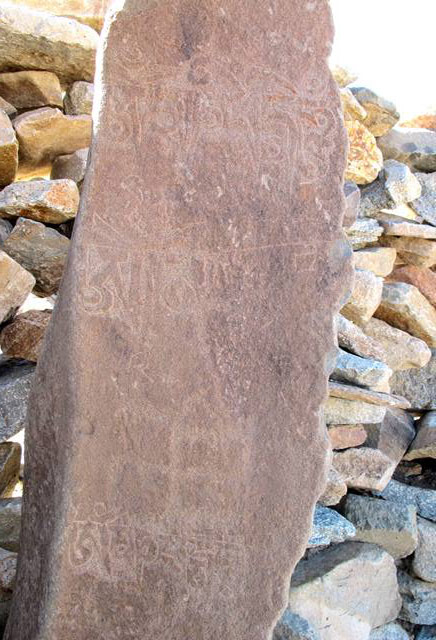

Fig. 49. Large counterclockwise swastika and what appears to be an incomplete swastika carved above an inscription reading: Khyung pho ma…bris (“Written by Khyung pho…”), northwestern Tibet.

The inscription refers to the Khyung po (sic) clan, as do several other short inscriptions in the same district. The orthographic and paleographic characteristics of the crudely scrawled inscription indicate that it was written in the Early Historic period, possibly in the Imperial period (ca. 650–850 CE). The small counterclockwise swastika at the end of the inscription was made by the same hand, while the larger swastikas may have been carved separately. This inscription reveals that some members of the Khyung po clan retained a non-Buddhist religious identity. The Khyung po were one of the most important clans of the Zhang Zhung kingdom and played an important political role in imperial Tibet.

Fig. 50. Here is another display of a non-Buddhist or bon religious theme, probably related to territoriality and the articulation of mystical doctrines, eastern Changthang. Circa 850–1200 CE. In addition to two counterclockwise swastikas, the syllable A and the mantra A’ Om hum were written.

Although the swastikas and surrounding pictographs may have been made by different individuals, they form a thematically interrelated array. The mantra A’ Om hum was used regularly by non-Buddhists in Upper Tibet, as the epigraphic record indicates, in contrast to the Buddhist mantra Om A hum. Like swastikas that face in opposite directions, these alternative mantras highlight the interplay between religious exclusivity and religious borrowing.

Fig. 51. Counterclockwise swastika and the syllable A, eastern Changthang. Early Historic period.

It is likely that these symbols of a non-Buddhist group relate to religious traditions known as Dzokchen (Rdzogs chen), a philosophical and mind training school spanning the divides between Buddhism and bon and bon and Yungdrung Bon.

Fig. 52. Counterclockwise swastika and the syllable A’ written in a white pigment, eastern Changthang. Probably Early Historic period.

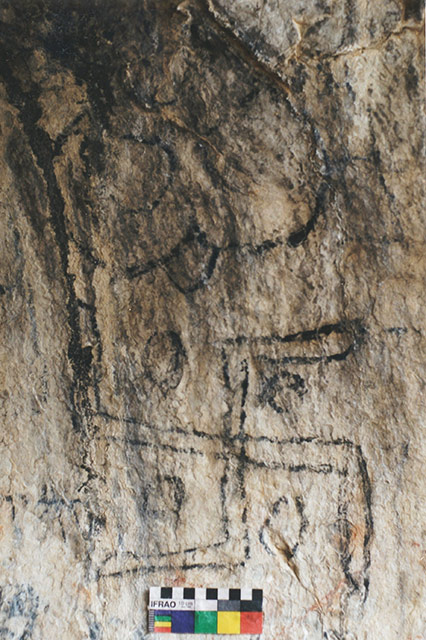

Fig. 53. A counterclockwise swastika painted in white and two shades of red ochre beside the primal syllable A. This painting is found on the wall of a ruined hermitage in the western Changthang, one associated with the great Dzokchen practitioner known as Tapihritsa (Ta pi hri tsa).

According to Yungdrung Bon tradition, Tapihritsa was an 8th century CE adept and the 25th and final member of a lineage of practitioners of Zhang Zhung antiquity. His lakeside hermitage is liable to have been vacated in the 11th or 12th centuries CE, but graffiti scrawled all over it indicates that old religious loyalties persisted even after the first Buddhist inroads in the region.

Fig. 54. Bichrome counterclockwise swastika, syllable A and two endless knots (pa tra), as well as a red ochre swastika and conch. Located on same structure as paintings in fig. 53. Circa 900–1200 CE. The letters are part of the beginning of a mantra for the Yungdrung Bon god Shenlha Ödkar (Gshen lha ’od dkar).

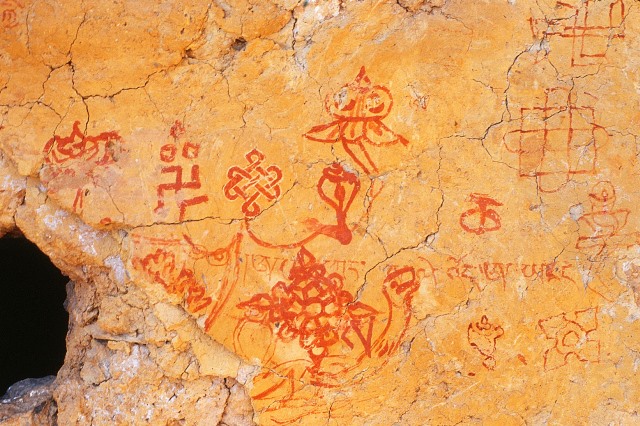

Fig. 55. Other figures painted on the hermitage in figs. 53 and 54, including Yungdrung Bon versions of the Eight Auspicious Symbols (Bkra shis rtags brgyad). Post-11th century CE. The mantra is for the god Shenlha Ödkar.

Fig. 56. A swastika with what appears to be the Om/A written thrice and ma once between its four legs. These mystic syllables appear to celebrate the dichotomous universe, consisting of the lower and upper worlds. This esoteric representation from the eastern Changthang was made by bonpo active in the region until about 1240 CE.

Fig. 57. A counterclockwise swastika with conjoined sun and moon surmounted by a teardrop motif that may have been added at a later date, eastern Changthang. This symbolic ensemble was made by bonpo prior to 1240 CE. It represents a singularity, such as the full gamut of religious traditions and/or the universe.

The development of indigenous religious traditions in Upper Tibet during the Early Historic period was largely propelled forward by the introduction of Buddhism. Tibet’s thirty-third king and its first imperial emperor, Songtsen Gampo (Srong btsan sgam po), paved the way for Buddhism to flourish in Tibet. He is credited with founding Tibet’s central cathedral in Lhasa, the Jokhang (Jo khang), as well as other temples around Tibet. His marriages to the Chinese princess Wencheng and the Licchavi princess Bhrikuti, women from Buddhist kingdoms, spurred on his missionary activities. Still poorly understood court politics and rivalries between aristocratic clans, however, seem to have played an even larger role in the spread of Buddhism in Tibet.

Despite his Buddhist activities, Songtsen Gampo was buried in a large funerary mound (bang so) in southern Tibet, indicating that archaic religious customs retained much prestige during his time. Buddhism continued to gain ground in Tibet in the reign of most successive kings, culminating in it becoming the state religion in the late 8th century CE. There would be political setbacks for Buddhism but by 1000 CE, it was firmly established in sundry areas of Tibet, effectively displacing earlier religious traditions.

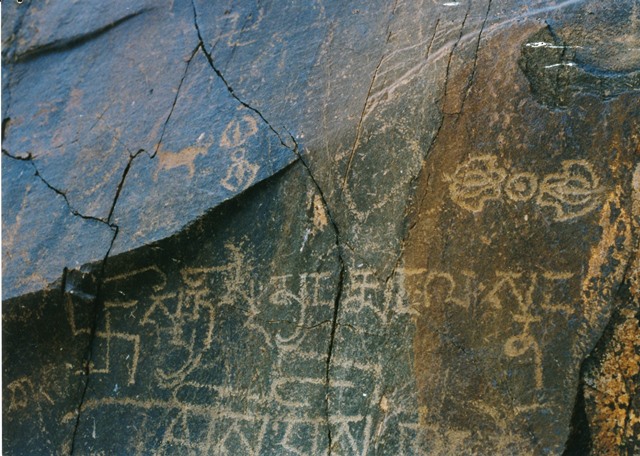

Fig. 58. A rock face chronicling Buddhist influences in northwestern Tibet during the imperial period. It is situated on an ancient east-west route between agricultural regions of the far west and the pastoral Changthang. Carved in a conspicuous location, this rock art and inscription was designed to be noticed.

Visible in the photo are two well carved ritual thunderbolts (rdo rje, symbol of tantric Buddhism). Note the older wild yak petroglyph next to one of the ritual thunderbolts. Higher up on the rock is a counterclockwise swastika, which may have been added as an ideological counterpoint or in political opposition to the Buddhist art and writing.

The inscription accompanying the thunderbolts is preceded by a clockwise swastika. This swastika serves to emphasize the momentousness of the inscription and illustrates that it was written under the auspices of Buddhism. It reads: spyĭ ti sde myang rmang la snang (ln. 2) gis bris khyung po (ln. 3) {tha} chun (= chung) gyĭs brgyis (mod. = bgyis) pa’o (“Written by Myang rmang la snang of the Spyĭ ti district. Done by the youngest Khyung po”). The accomplishment referred to in the third line appears to be the carving of the ritual thunderbolts, heralding a Buddhist occupation, at least in an abstract or legalistic sense.

The inscription in fig. 58 seems to include reference to the Spiti (Spyi ti) district (sde), one of five districts in Lower Zhang Zhung, a crucial part of the political geography of the Tibetan empire (see May 2015 Flight of the Khyung). If the western Tibetan region of Spiti is really intended here, this inscription is by far the earliest one known, preceding by four or five centuries mention in the well-known historical text of the 13th century CE, Lde’u chos ’byung. Like the inscription in fig. 49, this one is centered on the Khyung po/pho clan. As is well known, this large and highly influential clan had a dominant political function in western Tibet in the Imperial period, as demonstrated by both epigraphic and textual sources.

The thunderbolts, style of the script and the dedicatory nature of the inscription are closely related to Buddhist rock art and inscriptions in Ladakh. Such art and dedications are uncommon at western Tibetan rock art sites. This indicates that cultural influence for them probably originated in the north and west, where they are far more numerous. This is also true of early chorten rock art in western Tibet, which was heavily influenced by literary and artistic traditions already well established in Ladakh.

There are relatively few Buddhist inscriptions dating to the Early Historic period in Upper Tibet. This can be accounted for the by the slow spread of this religion to the region. The most common Buddhist inscriptions of the era consist of the mani mantra (Om ma ṇi pad me hum). Mani mantra inscriptions were also carved on rocks in the Vestigial period (1000–1250 CE) but after that time, this tradition of cutting letters was replaced by the relief engravings of mantras, which proliferated greatly in Tibet and remains very popular to this day. In addition to mani mantras, several other Buddhist mantras were etched onto rocks and cliffs in Upper Tibet during the formative period of this religion. The examples illustrated below were chosen because they are found in conjunction with the swastika.

Fig. 59. A mani mantra of the post-Imperial period (850–1000 CE) or perhaps somewhat later, central Changthang. Also on the same rock face are more recently carved swastikas (clockwise and counterclockwise) and other Tibetan lettering.

The mani inscription appears to chronicle the spread of Buddhism in the region after the fall of the Tibetan empire. It has been the single most common Buddhist mantra carved in stone since the Early Historic period.

Fig. 60. Buddhist rock art and inscriptions, central Changthang. Vestigial period. The upper inscription is the vajra mantra for Guru Rinpoche. Higher up on the rock face is another Buddhist composition which I have treated elsewhere. Although the swastika accompanying the syllable hum’ and bow and arrow faces counterclockwise, it is a Buddhist symbol. The detailed but clumsily executed horseman and standing anthropomorphic figure typify the decadence of Upper Tibetan rock art in the final period of production.

th century CE. This inscription as well as those in figs. 59 and 60 are located at the same site.” width=”640″ height=”457″ /> Fig. 61. A Buddhist inscription reading karma pa mkhyen no, a cardinal mantra of the Kagyu (Bka’ brgyud) sect. Post-11th century CE. This inscription as well as those in figs. 59 and 60 are located at the same site.

The advance of Buddhism in Upper Tibet is also documented in swastikas carved or painted on their own or with other symbols of the religion. However, Buddhist rock art is far less common in Upper Tibet than that of the older religious groups. Buddhist artistic energies in the Early Historic period were largely focused on fresco painting, sculpture and others media, which also circulated widely in central, east and south Asia. On the other hand, the bonpo of Upper Tibet continued to paint and carve natural stone surfaces, an indigenous tradition already some 2000 years old by the end of the first millennium CE.

Fig. 62. A boulder with an interconnected mass of clockwise swastikas, central Changthang. Early Historic period or Vestigial period.

The black and white drawing used as the banner for this newsletter is another example of unusual red ochre swastika rock art on the central Changthang, which seems to have been made by Buddhist practitioners in the Early Historic period or Vestigial period.

Fig. 63. Polychrome rock art consisting of clockwise swastika, ritual dagger (phur pa), ritual thunderbolt and bell (dril bu). Central Changthang. Probably Vestigial period.

This rock art is found in a cave that was evidently given over to Buddhist ritual labors. The artist chose to paint key symbols of his religion, as did those who painted counterclockwise swastikas in the same cave.

Fig. 64. A composition painted in black pigment (oxides of manganese or charcoal), consisting of the triple gems and a clockwise swastika, eastern Changthang. Vestigial period or later.

The encounter between non-Buddhist and Buddhist groups beginning in 7th and 8th centuries CE had a profound impact on the development of religious traditions in Upper Tibet. These interactions are graphically depicted in swastika rock art, which functioned as markers of sectarian identity and territorial control. Both the inspirational and conflictive sides of this epic exchange are represented in the rock art of highland Tibet.

Fig. 65. The imprint of non-Buddhist and Buddhist religions is trenchantly expressed in these two swastika pictographs, eastern Changthang. Circa Early Historic period. Both swastikas have had butter offerings added to them by pilgrims.

Fig. 66. Older and more recent swastikas embellishing a cliff at a site in the eastern Changthang, which appears to have witnessed vigorous interactions between Tibet’s contending religious traditions in the Early Historic period and Vestigial period. A deer and other figures are also seen on the same cliff.

Fig. 67. Two carved swastikas facing in opposite directions at the same site as fig. 66.Fig. 67. Two carved swastikas facing in opposite directions at the same site as fig. 66.

Fig. 68. A counterclockwise swastika painted along with a mantra, reading bso A pha. The mantra and swastika were made by practitioners of bon traditions in the eastern Changthang. It appears to extol a sage, doctrine or people referred to as ‘father’ (A pha). Vestigial period. The mantra to the left reads Om’ hum ram dza /. Its popular Yungdrung Bon counterpart is Om A hum ram dza. The darker red inscription on the lower left side of the image dates to the Imperial period and has been dealt with in my book Zhang Zhung. On the lower right side of the photo is a mani mantra (partially visible).

Rival religious factions were attracted to this same shallow cave to broadcast their faith. Competition for territory and hearts is implicit in this jostling of religious messages.

Fig. 69. Counterclockwise swastika appended to a mantra reading A phaṭ, eastern Changthang. Vestigial period. This mantra for expelling obstructions and negativities suggests that the companion swastika was a symbol of territorial occupation and/or ideological dominance. Note the old-fashioned ma and vowel sign of the syllable Om (part of a mani mantra) at the bottom right of the image.

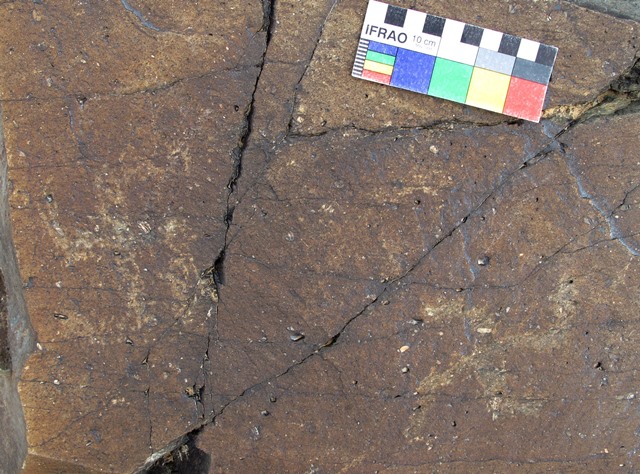

Fig. 70. A counterclockwise swastika partially carved over a portion of a raw stone surface.

In Upper Tibet there are several such examples of what appears to be the forced removal of stone surfaces that presumably had rock art or inscriptions of religious rivals on them. This appears to chronicle sectarian tensions or even violent encounters.

Fig. 71. Clockwise swastika painted over part of the Yungdrung Bon mantra for the god of boundless light, Shenlha Ökar, western Changthang. These red ochre indictments occur on the main foundation stone of a ruined hermitage (also see figs. 53–55). Vestigial period.

The superimposition of Buddhist symbols and especially mantras on older rock art was a common practice in Upper Tibet. This is some of the best documentary evidence we have for the subjugation of earlier religious traditions and the triumph of Buddhism in Upper Tibet.

Fig. 72. A counterclockwise swastika amid mantras, Buddhist and non-Buddhist, eastern Changthang. Vestigial period. In this period the rise of Buddhism in Upper Tibet came to overshadow what remained of archaic and alternative religious traditions.

Although the transition to Buddhism would prove irresistible, it was not until the early 13th century CE that most archaic and syncretic religious traditions disappeared in Upper Tibet. Moreover, in only a few small enclaves did the successor to early bon traditions, Yungdrung Bon, prevail in the region. The concluding part of this article features stylistic permutations of the solitary counterclockwise swastika, mostly dating to the Early Historic period. Probably because the religious organizations articulated by this symbol were on the defensive, there are many more examples of it than the clockwise swastika of the Buddhists. It is with much exuberance and regularity that counterclockwise swastikas were added to boulders, rock panels and caves in the Early Historic period, the most popular sign of non-Buddhist traditions in the Early Historic period and Vestigial period.

Fig. 73. Counterclockwise swastika superimposed on a depiction of wild ungulate, eastern Changthang.

Fig. 74. Counterclockwise swastika with butter applied to it in a devotional exercise, eastern Changthang.

Fig. 75. Counterclockwise swastika painted in a crimson hue, eastern Changthang.

Fig. 76. Well-formed counterclockwise swastika, eastern Changthang.

Fig. 77. Large, thin counterclockwise swastika, eastern Changthang.

Fig. 78. Double-lined counterclockwise swastika, eastern Changthang.

Fig. 79. Counterclockwise swastika and more recent mani mantras added to a prehistoric funerary ritual pillar, northwestern Tibet.

Fig. 80. Clockwise swastika engraved on prehistoric funerary pillar at same site as fig. 79.

Fig. 81. Three different red ochre counterclockwise swastikas and conjoined sun and moon in rear of large, round cave, eastern Changthang. This early style conjoined sun and moon is also seen in copper alloy talismans (thog lcags). As with stepped shrines and flaming jewels, it was once favored by both Buddhists and non-Buddhists.

Fig. 82. Three white counterclockwise swastikas of the Vestigial period in the same cave sanctuary as fig. 38.

Fig. 83. Three counterclockwise swastikas, asymmetrical swastika, quadruped and other figures, northwestern Tibet.

Fig. 84. Recently painted counterclockwise swastika obscuring earlier rock art, eastern Changthang.

Made with a synthetic paint in the last decade, this swastika was drawn by Yungdrung Bon pilgrims intent on reclaiming the site from Buddhists. In close proximity and in the same paint, is the eight-syllable mantra of Yungdrung Bon preceded by the line theg chen gyi gnas mchog bon (“Bon pilgrimage site of the great vehicle”). Although it reflects modern sectarian fault lines, this defacement of the site is part of a struggle that can be viewed through a prism refracting Tibetan history for 1200 years.

Next Month: The prehistoric tradition of wild yak hunting in Upper Tibet!