June 2013

John Vincent Bellezza

This month’s Flight of the Khyung takes you to ancient Ladakh, the westernmost part of the Tibetan plateau! We shall explore its early history and monuments from new perspectives. To help us in our quest is Quentin Devers, a young French archaeologist who has spent the last few years surveying the ancient strongholds of Ladakh. He has kindly contributed a highly informative article on the stone-roofed structures of Ladakh to this newsletter. To complement his study, I shall provide additional information on one site of particular interest, Nyarma. This is followed by a review of the ancient history of Ladakh and Zhang Zhung, touching upon prospects for new breakthroughs in this nascent field of comparative study.

A supplement reviewing two more genetic studies now appears at the end of the May newsletter. These papers add to mounting evidence for the Palaeolithic origins of the Tibetan people. It is also with much pleasure that I announce the publication of my new book, the fruit of several years of work.

New book announcement

Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften

Philosophisch-Historische Klasse Denkschriften, vol. 454

Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet

Archaic Concepts and Practices in a Thousand-year-old Illuminated Funerary Manuscript and

Old Tibetan Funerary Documents of Gathang Bumpa and Dunhuang

(x + pp. 293, 2 maps, 40 color plates, 16 illustrations)

This monograph brings to light the eschatological patterns and procedural constructs of death rites in ancient Tibet. It is centered on documents written between circa 800 CE and 1100 CE, which include an illuminated funerary manuscript of much rarity, two death ritual texts recently recovered in southern Tibet from the Gathang Bumpa religious monument, and several related manuscripts discovered in the Dunhuang grottoes a century ago. This book builds upon previous efforts of the author to explicate the otherworldly dimension in early Tibetan religion and culture. Many of the documents of this study were written in the Old Tibetan language and represent the oldest known literary sources for research into Tibetan funerary traditions. The work is underpinned by annotated translations, which are critically edited and painstakingly provided with Classical Tibetan word equivalents.

Each featured text is described in detail and subjected to a rigorous religious and historical analysis. Other Tibetan literature that supports the comprehension of the foundational texts of this study is also marshalled. These textual assets complement one another by progressively revealing an indigenous belief system and praxis of great depth and intricacy. The antiquated narrations and rituals concerning death presented in this book furnish a lucid view of cultural forms that circulated around Tibet before its religious universe became saturated with Buddhism and Buddhist-influenced doctrines and practices. Especially when seen through the lens of the archaeological record, the sheer intellectual and material wealth borne in the archaic funerary traditions demonstrates that Tibet was endowed with culturally advanced societies in the time before the spread of Lamaism. Bibliographies and indexes (with glossary) are appended to the main text.

To order this book, see the publisher’s link: http://hw.oeaw.ac.at/7433-2

The stone-roofed structures of Ladakh

By Quentin Devers

Introduction

Nyarma (Nyar-ma) is located in the heart of central Ladakh, on a plain where the Indus valley is wide and covered with well-irrigated fields. It is best known for its religious compound, founded by Lotsawa Rinchen Sangpo (Lo-tsa-ba rin-chen bzang-po), a main actor in the second spread of Buddhism (circa 1000 CE). The main temple is his only attested construction in Ladakh. Although famous, the complex is in ruins and has been for centuries, thus it has been the object of only a few studies (mainly by Jampa L. Panglung, Holger Neuwirth & his team, and Gerald Kozicz). The castle, located on the hill overlooking the monastic compound has received even less attention: only Neil Howard documented it in the 1980s. Howard provides a description of it in papers on the fortresses of Ladakh (see Howard in bibliography below). This castle is unique: it is the largest among the few stone-roofed defensive monuments still standing in the region.

As I have written a more detailed study of the Nyarma castle in a forthcoming paper (see bibliography), and as John V. Bellezza is providing his own study of this structure in light of those he has documented all over Upper Tibet, I will primarily focus here on an overview of stone-roofing techniques in Ladakh, as well as furnishing a short review of ancient sites in the region.

Stone roofs

Stone-roofed structures in Ladakh are attested in ancient monuments, although they are not nearly as common as in Upper Tibet. Neither do they attain the same level of development as on the high plateau, where bridging stones can be as long as 2 m (Bellezza 2008, p. 33), and where ceilings can be particularly impressive as at Gzims-phug (ibid., fig. 1, p. 33), or at the three-story high tower of Tho-phu. However, the position of Ladakh is quite different than that of the high plateau: the density of population is significantly higher and desertification does not appear to have been so devastating. Thus, Ladakh has retained a strong agricultural base and important population centers. As a result, many places have been continuously inhabited for centuries, if not millennia. Locations that are inherently defensive in nature have been upgraded and rebuilt over time. A variety of stone-roofed monuments therefore must have been lost in this process. Another reason for the relative scarcity of stone-roofed monuments in Ladakh is that it has likely been a region of mixed populations, mixed cultures, and mixed traditions since time immemorial. We will come back to this notion in the review of ancient sites in the region.

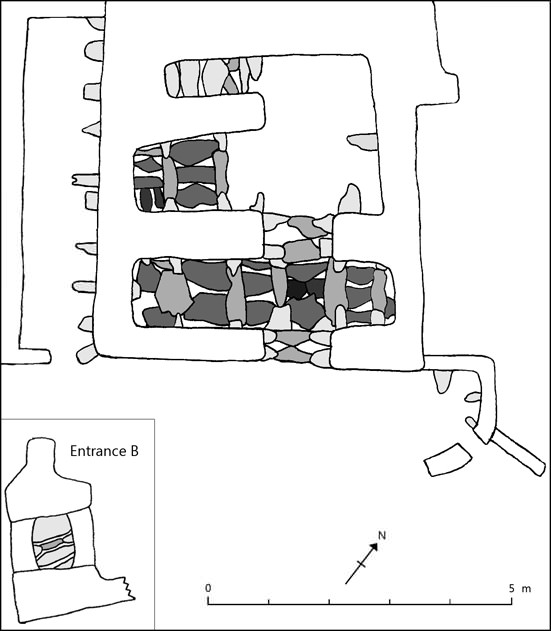

Thanks to indications provided by my colleague Martin Vernier, I have documented three fortifications or towers that are entirely stone-roofed. The smallest of these is at Rumbag. It is a small square tower standing on the edge of a low cliff (fig. 2). It contains a single room measuring approximately 2 m x 3 m (fig. 3).

Fig. 5. The original tower of Chemre is on the right. It was built with buttresses. The wall extension to the left was built at a later date with stones of a more greyish color.

The second tower site is at Chemre. Standing on a thin rocky outcrop, this two-story square structure has a room about 2 m x 2.5 m in size (figs. 4, 5). Built with buttresses, it is one of the very few edifices with such a structural feature surveyed so far in Ladakh. This tower was later extended with an elongated construction, also entirely stone-roofed (fig. 6). While the original tower is windowless, the extension has small openings on both faces. The fact that these two towers have relatively low elevations, are quite reduced in size, and do not feature loopholes probably indicates that they were not particularly defensive in function, but rather symbolic displays of power.

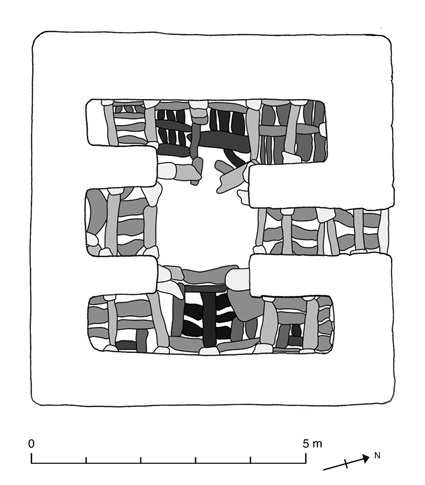

Fig. 9. Plan of the stone roof at Nyarma. Stones are represented as if seen from underneath: stones of a darker color are laid over stones of a lighter color.

Fig. 10. Plan of the stone roof of the Kadampa (Bka’-gdams-pa) chorten (mchod-rten) in Stok. Stones are represented as if seen from underneath: stones of a darker color are laid over stones of a lighter color.

The third and by far most developed site is Nyarma (fig. 7). The main building consists of the remains of a D-shaped tower in the rear, in front of which is a group of rooms. A rampart encloses an open space in front of the building, giving the site its defensive quality. The rooms are larger than in the towers of Rumbag and Chemre. In order to achieve this size, a particular roofing technique was used (fig. 8). It consists of two opposing corbels with a bridging stone over them. These corbels and bridging stones are spaced at regular intervals. Finally, transversal bridging stones were laid to close the remaining space. This building technique consists of three structural levels: 1) corbels, 2) bridging stones, and 3) transversal bridging stones. This technique allowed for the construction of large stone-roofed monuments in Ladakh. It creates spaces that are elongated in shape (fig. 9). Where similar plans can be observed, this technique is used in all the structures that are larger than a couple meters. One example is the Kadampa chorten in Stok (fig. 10). In order to achieve a chorten of this size, the same corbelling technique was used. We can see that the internal spaces are similarly elongated and the overall plan is quite similar.

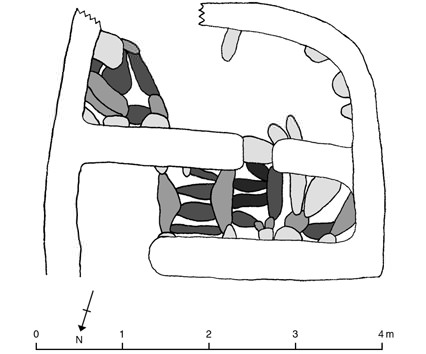

Fig. 11. View of the stone roof of one of the cells at the Nyarma hermitage, located on the hill east of the Nyarma fortress.

Fig. 12. Plan of the roof of one of the cells of the Nyarma hermitage. Stones are represented as if seen from underneath: stones with a darker color are laid over stones with a lighter color.

Fig. 13. View of the small temple on the hill at the Nyarma hermitage. Note the two narrow corridors along its front and right wall.

Beside fortresses and towers, there are other constructions that are stone-roofed. These include religious structures such as cells and chortens, residential rooms, and other rooms with uncertain functions. One example of the first type is very close to the fort. On a hill due east, stands a small complex comprised of a ruined temple, several ruined cells, and decayed chortens. The cells were stone-roofed, and a few of them still retain their original ceilings (fig. 11). We can see that the technique used is a small-scale version of that deployed at the fort, consisting of the same three structural levels (fig. 12). The temple is interesting for its architecture (fig. 13). It is small in size and it walls are entirely built with stones. Although it doesn’t feature a stone roof, it has stone lintels over the doorways. The two narrow corridors along its front and right wall might also have included stone roofing elements.

All of these traits contrast with the temples of the compound founded by Lotsawa Rinchen Sangpo in the plain below. These temples are all built with mud bricks, feature only wooden lintels, and otherwise make heavy use of wood, as with with beams to span the 13 m-long assembly hall in the main temple. We can see here two radically different types of construction. One is based on stones and includes traits such as reduced-size rooms and stone-roofing elements. The other is based on earth and wood, including elements such as large rooms, long beams, and the use of pillars. In this respect, the small temple and its surrounding cells on the hill are architecturally much closer to the fort: they share the traits and characteristics of what was likely a continuous architectural culture. The temples of the compound, on the other hand, issued from a different tradition of construction.

Other structures are also part of this old architectural tradition of stone constructions. In the Sabu valley, at the foot of Tomba Khar, a series of semi-subterranean rooms are all stone-roofed. These simple rooms, located in the vicinity of a fortification, might have had a residential purpose. In Takkar Ramaruchik Khar, another stone-roofed room is to be noted on the flat hilltop. This area is landscaped with terracing and other stone walls that appear to be older than the rest of the site. Among these structures is the stone-roofed room, the ceiling of which is partly collapsed. The purpose of this hilltop site is difficult to assert at present – perhaps it was ceremonial?

Finally, while the large temples of the religious compound at Nyarma introduced a rupture in the old architectural culture with the introduction of a radically different form of construction, other monuments created a link between the old stone architecture and the new building culture that diffused with the second spread of Buddhism. These hybrid monuments are mainly chortens and other small structures such as lhatho-s (lha-tho) or tsatsakhang-s (tswa-tswa khang), in which the use of stone corbels is adapted to a reduced internal size. In a forthcoming article written with Laurianne Bruneau and Martin Vernier, we describe ten early painted chortens among which five feature stone roofs (see bibliography).

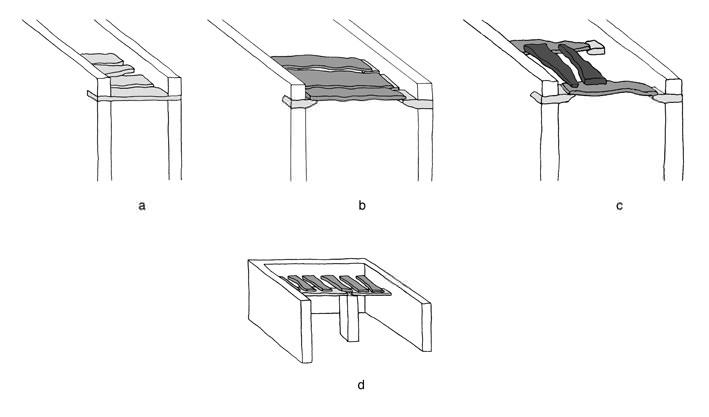

Stone roofs in Ladakh can be categorized in four main techniques of construction, as represented above:

Technique A: Bridging stones go directly from one wall to the other (hence a single structural level).

Technique B: A first layer of corbels is used in order to support a second level of bridging stones (hence two structural levels);

Technique C: Corbels spaced at regular intervals are the support of bridging stones, over which transversal slabs are laid in order to close the remaining space, as found at the Nyarma fortress (hence three structural levels).

Technique D: A central stone pillar is used. It supports two bridging stones, over which are laid a second layer of transversal stone slabs. This technique was first surveyed by Martin Vernier, and to our knowledge, is quite unique in Ladakh. It has only been observed in a series of chortens at Nang.

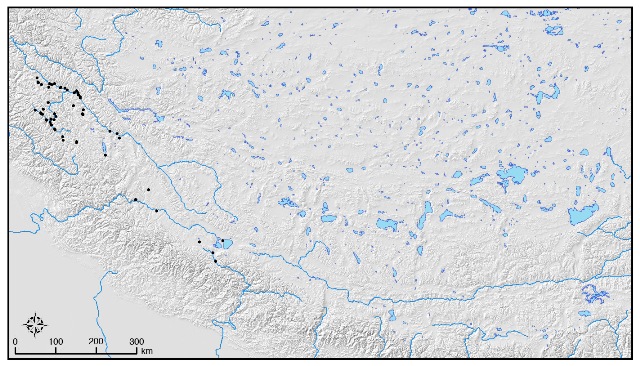

Early sites of Ladakh

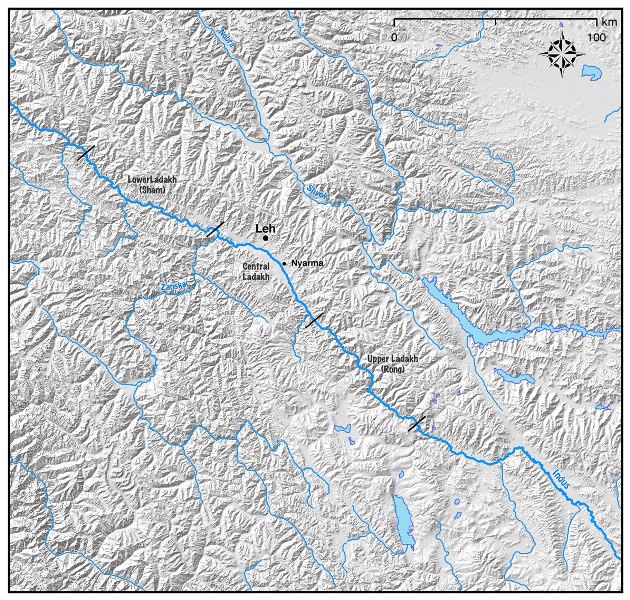

A variety of ancient sites are scattered all over Ladakh. By ‘ancient’, we signify those sites that present a number of characteristics that appear to be archaic, as compared to sites whose foundation is documented in the Ladakh Chronicles or other written sources. These archaic sites do not form a homogenous corpus: one can clearly distinguish distinct traditions of construction, spatial conception and configuration, as wells as topographical and environmental differences. The impression received from these data is that Ladakh was not the territory of a single cultural group. It was instead probably inhabited by different cultural and/or ethnic groups. One can also notice that sites with stone-roofs sharing ties with the Upper Tibetan world are all located upstream of the confluence of the Indus river with the Zanskar river. On the other hand, rock inscriptions written in ancient Indian scripts (like Brahmi or Karoshti) are all situated downstream of this confluence. In addition to supporting various cultural groups, Ladakh might also have been divided between several political entities. However, we still know little about Ladakh’s ancient history: even the name of the region before the 10th century is in question. It is the goal of work being carried out with Laurianne Bruneau and Martin Vernier to reconstruct parts of this long and little known history (for more information visit our website: www.tedahl.org)

Conclusion

It is important to emphasize that the observations made below are for the moment only hypotheses. The Nyarma fortress undoubtedly belongs to a group of sites that display ties between Ladakh and the Upper Tibetan world during the protohistoric period. It has to be understood in light of the history of a region in which a number of different cultural groups cohabited and probably influenced one another. For example, one peculiar detail at Nyarma tends to point to such influences: the rear structure is D-shaped. Such a curvilinear shape contrasts with sites studied by John V. Bellezza on the high plateau – quadrangular structures are the rule there. This shape is not accidental: many sites in Ladakh feature circular towers, such as Stok Mon Khar, which was the subject of September 2012 issue of Flight of the Khyung (also see the January 2011 issue ). While some architectural elements clearly point to strong contacts with Upper Tibet, others do not.

It is also important to keep in mind that we don’t know what the political organization of Ladakh was in early times. Different parts of the region might have fallen under different political entities, either indigenous or foreign. Such entities trying to coexist in a single territory may have been subject to games of power with political and religious consequences. For example, if a rival entity further downstream had privileged links with the Indian world and that entity was expanding towards Nyarma, we could imagine that a local ruler there may have sought the protection of one of his powerful neighbors in Upper Tibet. As a mark of friendship, he could have decided to adopt the architecture of his new protectors for the construction of a fort. The main attribute of this architecture would have been the stone roof, while some local customs would have been perpetuated such as the D-shaped tower at the rear. This hypothetical example will suffice to show that the ancient monuments of Ladakh cannot be approached using the same historical methodologies as monuments of other regions such as Upper Tibet: they represent a framework in which one has to distinguish the origins and chronology of still obscure groups of people. Without appropriate historical documents and without proper archaeological research, one must as such remain very careful as to the interpretation of ancient sites in a region with a heritage and a history as rich and varied as Ladakh.

Bibliography

Bellezza, John, V. 2008, Zhang Zhung. Foundations Of Civilization In Tibet: A Historical And Ethnoarchaeological Study of the Monuments, Rock Art, Texts, and Oral Tradition of the Ancient Tibetan Upland. Vienna, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Devers, Quentin. Forthcoming. “An Archaeological Account of Nyarma and its Surroundings, Ladakh, in Material on Western Tibet”. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Devers, Quentin; Bruneau, Laurianne; and Vernier, Martin. In press. “An Archaeological Account of Ten Ancient Painted Chortens In Ladakh” in Ladakhi Art and Architecture – Proceedings of the 11th colloquium of the International Association of Ladakh Studies, E. Lo Bue and J. Bray (eds.). Leiden, Brill.

Howard, Neil. 1995. “The Fortified Places of Zanskar” in Recent Research on Ladakh 4&5. Proceedings of the Fourth and Fifth International Colloquia on Ladakh (eds. H. Osmaston and P. Denwood), pp. 79–99. London, School of Oriental & African Studies.

Howard, Neil. 1989. “The development of the fortresses of Ladakh c. 950 to c. 1650 AD” in East And West, vol. 39, pp. 217–288. Roma, Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

Kozicz, Gerald. 2007a. “Do the Wrong Thing. Some Remarks on the Architectural History of the Former Sacred Compound of Nyarma and Current Construction Activities”: http://www.tibetheritagefund.org/media/forum/Berlin_conf_paper07/kozicz_berlinpap.pdf.

Kozicz, Gerald. 2007b. “The Architecture of the empty shells of Nyarma” in Discoveries in western Tibet and the western Himalayas: Essays on history, literature, archaeology and art: PIATS 2003, Tibetan studies, proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Oxford, 2003, A. Heller and G. Orofino (ed.), pp. 41–54. Leiden, Brill.

Neuwirth, Holger. 2008. “Buddhist Architecture in the Western Himalaya: http://www.archresearch.tugraz.at/ [consulted on 5th October 2008].

Panglung, Jampa Losang. 1983. “Die Überreste des Klosters Nyarma in Ladakh” in Contributions on Tibetan Language, History and Culture, Proceedings of the Csoma de Körös Symposium held at Velm/Vienna, Austria, 13-19 September, 1981, E. Steinkellner and H. Tauscher (eds.), pp. 281–287. Wien, Arbeitskreis für Tibetische und Buddhistische Studien, Universität Wien,

Quentin Devers, the author of the above article, is currently doing a Ph.D. on the archaeology of Ladakh at the École Pratique des Hautes Études (Paris). His research focuses on the fortified sites of Ladakh (watch towers, forts, defensible settlements) from protohistory to the late historical period. He began fieldwork in Ladakh in 2007.

Working closely with Laurianne Bruneau and Martin Vernier, Devers has carried out extensive surveys throughout Ladakh. Besides fortifications, his interests include construction techniques of other built structures such as ruined temples and early chortens. With this data he also investigates ancient networks of routes.

Devers worked for two years on GIS applications at the Tibetan and Himalayan Library (University of Virginia). Recently, he participated in archaeological surveys in Australia, where rock art, like in Ladakh, is one of the main material resources for the study of ancient cultures.

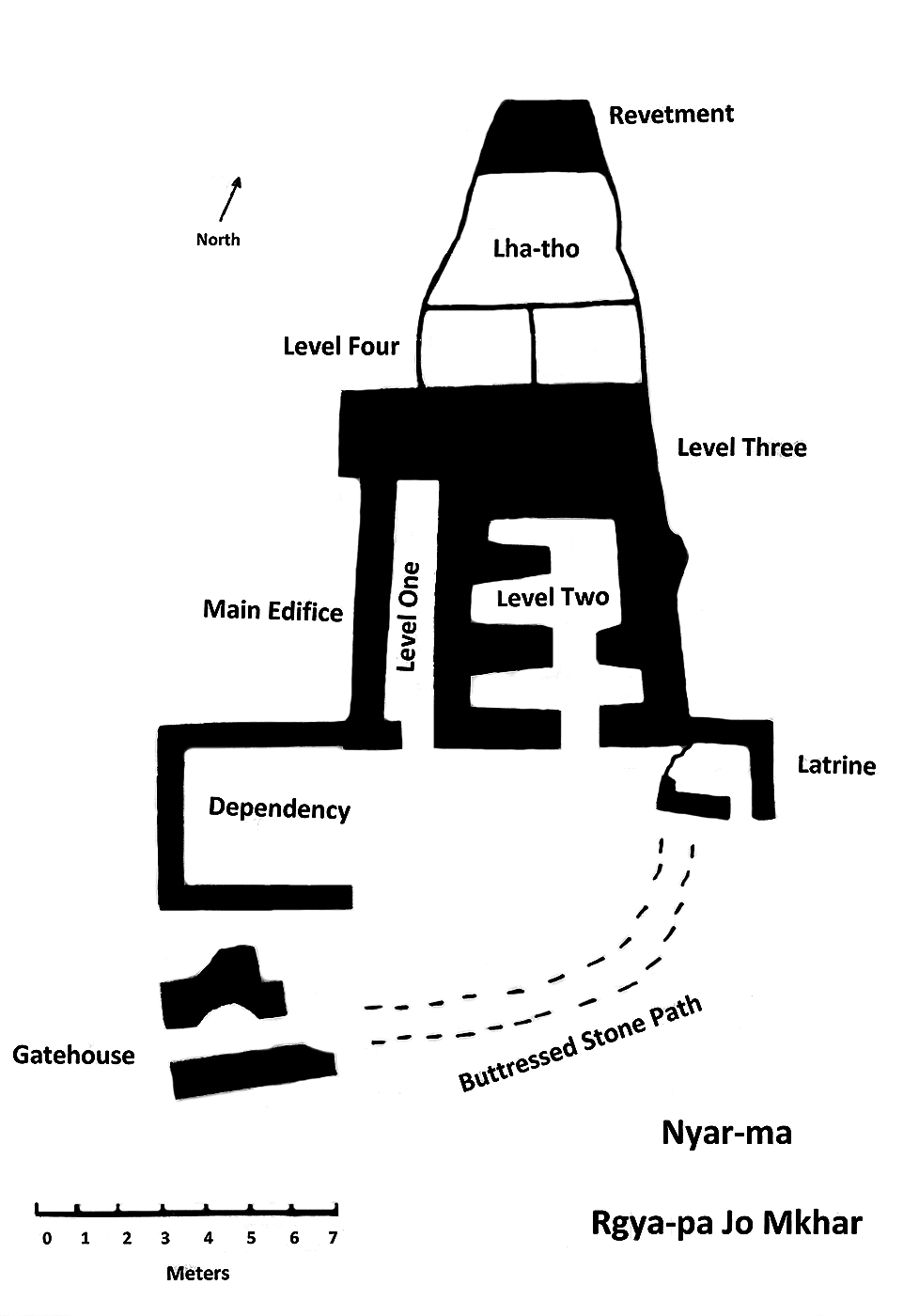

Gyapa Jo Khar of Nyarma

Introduction to Gyapa Jo Khar

As readers know from Quentin Devers’ contribution that precedes this article, there are the remains of a stone-roofed castle in the village of Nyarma. This site commands long vistas in most directions and is a prominent landmark that can be seen from afar. The castle at Nyarma was beautifully designed and built, a tribute to the engineering prowess of the ancient Ladakhis. Given its special set of architectural features and relatively intact condition, this monument deserves to be better known to aficionados of Himalayan history and culture, including the Ladakhis themselves. As Devers observes, this installation is linked to the ancient architectural traditions of Upper Tibet, raising questions as to the precise nature of these historical ties. It is the Upper Tibetan question that most concerns me, thus this special issue of the newsletter devoted to the corbelled architecture and early history of Ladakh.

The old castle at Nyarma is locally known as Gyapa Jo Khar (Rgya-pa jo mkhar); Gyapa being the name it is said of the ruler who built and occupied it. According to the local oral tradition, the main trade route coming from India into the upper Indus river valley was at one time controlled from Gyapa Jo Khar.* However, there is scant evidence to equate the Gya of the fortress and its ruler with the Tibetan and Ladakhi word for India (Rgya-gar), as some Ladakhis seem to believe. Another oral tradition holds that the name Gya is derived from the one hundred (brgya) households of the Gya village (Vohra 1995: 221). This account is also apocryphal. In fact, the word gya has many different meanings in Ladakhi and Tibetan. Gyapa in this context probably means ‘He of Gya’, Gya being the ancestral village of the Gyapa rulers located 50 km to the south of Nyarma. In the once important village of Gya there are other ruins attributed to Gyapa as well. Gya occupies a strategic location with routes linking it to Lahoul Spiti, Zanskar, the Ladakhi Changthang, as well as the Indus river valley. The Tibetan word jo (jo-bo) is a common political and religious title that means ‘master’, ‘lord’ of ‘chief’. The Tibetan term khar (mkhar) is best defined as ‘castle’ but it can also refer to palaces, garrisons and monastic facilities.

* My main local informant in Nyarma was Tashi Dorje (aged 48) whose house is close to the castle. Reportedly, his ancestors maintained their residence at the base of the hill upon which Gyapa Jo Khar was built until it was destroyed in a flood. I also spoke with a number of monks and lay people who hail from Nyarma during my May 2013 visit.

The local oral tradition maintains that Gyapa Jo Khar was constructed in the period before the Buddhist monastery of Nyarma was founded, circa 996 CE. This is confirmed by historical sources indicating that a Gyapa ruled the upper Ladkah principality of Gya (Rgya) prior to it being conquered by the Tibetan King Nyimagoen (Nyi-ma mgon), in the first half of the 10th century CE (Vitali 1996: 324, 325; Vohra 1995: 220, 221). Gya is also the clan name of the rulers of the eponymous principality or chiefdom (there was also a Gya region and clan in Tibet). In one classification of western Tibetan clan regions, Gya is listed along with Guge (Gu-ge) and Choge (Co-ge; Vitali 1996: 325). According to the La dwags rgyal rabs, Upper Ladakh (La-dwags stod) was ruled by those belonging to the lineage of Kesar (Ge-sar). Vitali (1996: 325–327) maintains that the Kesar lineage and thus the Gya clan were of Dardic stock. Nevertheless, Ge-sar is considered a descendant of the Ldong proto-tribe of Tibet (Karmay 1998: 260), as is the Gya clan (Vitali 2004: 6). Although Kesar was a well-known title and genealogical attribution adopted by Iranic and Dardic rulers, Gyapa Jo may have been of Tibetan, not Dardic origins, assuming the ancestry of Ge-sar through Bodic clan traditions. A ruler acknowledging Tibetan origins rather than Dardic ones fits the Upper Ladakh cultural environment better, especially after the advent of the imperial period and the Tibetanization of Ladakh. If this is the case, Gyapa Jo or his predecessors may have claimed the Kesar mantle in response to the social prestige of rival powers in the west.

In a recent interview with Tashi Rabgye (Bkra-shis rab-rgyas), a well known Ladakhi scholar, he expressed the opinion that Gya was a long-lasting ruling family. If so, the name popularly attached to castle in Nyar-ma does little in itself to help us judge its age, except to indicate that Gyapa Jo Khar was built before the mid-10th century CE.

Nyarma and surrounding villages constitute an important agricultural resource in Upper Ladakh, furnishing a significant economic base that must have had some bearing on the founding of Gyapa Jo Khar. Trade and tribute notwithstanding, the natural endowment of Nyarma has been instrumental in the long-term prominence of the village.

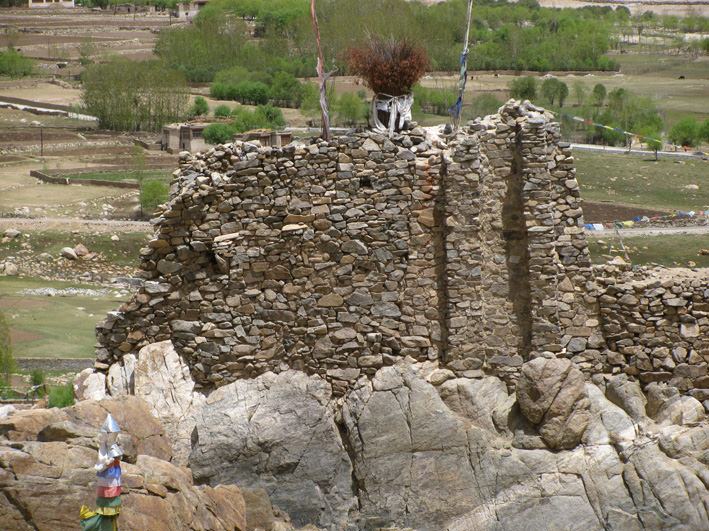

Gyapa Jo Khar castle occupies a craggy spur rising 50 m above the valley floor. The location is defensible but not particularly so, as the hill upon which it sits is not very high and the facility is vulnerable to being outflanked especially from the north. There are however small ramparts staggered along the south face of the steep spur. These defensive works were probably designed for use by archers and slingers. Networks of short ramparts built above one another are commonly encountered among archaic strongholds in Upper Tibet. The high revetment upon which Gyapa Jo Khar was built also potentially afforded it some protection from a marauding force. The ramparts and revetment are also likely to have enhanced the socially exclusivist identity of Gyapa Jo Khar, figuratively signifying its lofty status.

Gyapa Jo Khar was a relatively small installation where only a minimal contingent of defenders could have been garrisoned on a permanent basis. Rather, it appears to have been an elite social facility occupied by a local ruler or dignitary. The entire facility probably had around one dozen smallish rooms, which is more in keeping with the domicile of a family or other tight knit social unit. The high quality stonework of the castle and its all-stone corbelled roofs are also indicative of a prestigious residence. Moreover, attribution to a privileged component of society is supported by the local oral tradition assigning the site to a famous chieftain. We might therefore conclude that Gyapa Jo Khar most likely functioned as a ‘palace’.

Description of the castle

Fig. 17. A view of Gyapa Jo Khar from the west. From right to left: gatehouse, dependency, main edifice, lhatho resting on a D-shaped revetment.

Gyapa Jo Khar consists of a main edifice and three smaller outbuildings, all of which sit atop a long, rocky spur jutting far out into the valley floor. These structures have random-rubble walls with variable length (up to 50 cm), mostly uncut, white granite and a dark-colored grainy rock.

Fig. 18. The so-called gatehouse with barricaded entrance can be seen on the right side of the image. To its left is the dependency and behind it is the upper portion of the main edifice.

Access to Gyapa Jo Khar is via the west and south sides of the spur. The recently refurbished trail seems to more or less follow the same route as its ancient predecessor. This trail leads to a narrow opening (as little as 1 m wide) between the dependency and gatehouse. There is no structural evidence to indicate that this gap was once barricaded, thus it may have possibly functioned as one entry point into the castle.

The ‘gatehouse’ lies to the south of the gap between it and the dependency to the north. As much of the gatehouse has been destroyed its original size cannot be ascertained. The function attributed to this building is based on its intact outer entranceway (1.2 m x 70 cm), complete with stone lintel. The diminutive size of this entrance, nevertheless, may suggest that it was not the main access point to the castle. It opens to a narrow rubble-choked passageway (4 m x 1 m) that rises up about 2 m from the entrance. It must have once had stone steps but none remain. In the middle of the passageway is a corbelled vault about 3 m in height and narrowing towards the top to only 50 cm in width. The high ceiling space of this vault may possibly be indicative of ceremonial functions associated with the gatehouse. The corbelled vault was simply but competently constructed using a beehive technique of overlapping small stones without the benefit of bridging stones. This kind of architectural feature is not found in the archaic (pre-11th century CE) residential sites of Upper Tibet. Nevertheless, its construction is not unlike the more rudimentary roofs of shelters at Yama Chorten (G.ya’-ma mchod-rten), on the north side of the Himalaya in Upper Tibet (see Bellezza 2011). The inner side of the gatehouse passageway is connected to the faint remains of a stone buttressed walkway (approximately 15 m in length), which ascends 5 m to the main entrance of the main edifice of Gyapa Jo Khar.

The structure to the north of the gatehouse is set 1 m higher on the summit and its walls are around 3 m in height. The peripheral position, lighter and rougher construction, and diminutive size of this dependency indicate that it served a subsidiary function to the main edifice of Gyapa Jo Khar. This structure may have possibly housed military, administrative or service personnel attached to the installation. The dependency (4.4 m x 3.9 m) appears to have consisted of a single room. Its lightly built walls (around 40 cm thick) and the long spans involved demonstrate that this building had a roof of wooden timbers, not stone corbels. However, along the lower reaches of the walls there may have been a line of sockets, which could have possibly accommodated corbels, spanned by wooden beams to create a low-elevation basement. Basements with stone flooring above are found at Stok Mon khar and various citadels in Upper Tibet. Also, there is structural evidence for the possible hybrid application of stone corbels with wooden rafters at Gonpo Wangchuk Khar (Mgon-po dbang-phyug mkhar), in the headwaters region of the Brahmaputra valley (see Bellezza 2011). Also see Sutlej River Citadel (May 2012 Flight of the Khyung).

Fig. 20. The southern aspect front of the main edifice. Note the tapering walls in the ‘Tibetan fortress style’.

The main edifice of Gyapa Jo Khar (approximately 14 m long and 6.1 m wide) rests upon a dome of solid rock. Its walls slope inwards towards the top in the ‘Tibetan fortress style’ of construction. While common in Central Tibet, this style of construction is rarely seen in the corbelled residences of Upper Tibet. The main edifice is comprised of a separate west wing (level one), a latrine on the southeast corner, and the main structure (levels two, three and four). As described by Devers above, the roofing technique entailed three layers of stones: corbels, bridging members and transversal bridging members. While rare in Ladakh, this is the major style of corbelling found throughout Upper Tibet. There are also more elaborate corbelled structures in Tod (Stod) and Changthang (Byang-thang). For example, abbreviated corbelled arches with corbels laid at right angles to the walls are found at Zim-phuk and Phurbu Gyangmar (Phur-bu rgyang-dmar; see Bellezza 2011).

The west wing (1 m to 1.2 m by 6 m) of the main edifice is immediately adjacent to the dependency. The floor of the west wing is at the same elevation as the top of the walls of the dependency, the difference in height being made up by the revetment. The west wing had a separate entranceway (now destroyed) in the south. The function of this long narrow room is not apparent. The outer or west wall of the west wing is 50 cm to 1 m thick, creating a robustly built structure like the rest of the main edifice. A line of ten corbels protrudes from the east wall of the west wing. These corbels are set 2.5 m above the floor and once supported the roof over the west wing. There are no corbels on either the north wall or west wall of the west wing. This may suggest that much of the roof of the west wing was composed of timbers that rested upon the corbels along the east wall. According to Devers (forthcoming), the gatehouse, dependency and west wing were probably later additions to the site. He makes his assessment based on the plans, relative position and differing wall fabrics of these structures and the main edifice.

The latrine was also corbelled (three are still in situ). The function of this structure is derived through an examination of the opening in the outer / south wall at ground level. This opening overarched by a stone lintel is typical of that conveyed to a latrine pit. Such dry latrines are found in many castles of Ladakh and Upper Tibet and were built over a very wide period of time. The south, east and north walls of this masonry structure are 1.5 m to 2 m in height, while the west wall is the formation itself.

The main entranceway to the main edifice is in the south. This entrance (2 m x 1.2 m) is unusually large for an all-stone corbelled building. What large entranceways are encountered in analogous constructions of Upper Tibet belong to the early historic period (650 – 1000 CE) and are Buddhist temples.* Such entrances are found at Riu Gonpa (Ri’u dgon-pa) and Zimphuk (Gzims-phug; see Bellezza 2011). The large entranceway of Gyapa Jo Khar, however, may not be indicative of the same time period, because the small chambers of its second level are of the kind and layout exhibited by many protohistoric (150 BCE to 650 CE) edifices of Upper Tibet. Like the corbelled vault of the gatehouse, extremely high revetment and tapering outer walls, large entranceways seem to reflect a regional tradition of architecture distinguishing itself from that of Upper Tibet. In the absence of chronometric data, the age of Gyapa Jo Khar remains in question. In any case, it is very unlikely to have been founded any later than the Tibetan imperial period (650–850 CE). Radiocarbon dating of samples recovered from corbelled and what may have been corbelled monuments in Upper Tibet have been dated to the second half of the first millennium BCE or perhaps slightly later (see Bellezza 2008, pp. 35–37). The terminus a quo for this style of architecture remains to be determined.

* As the overall historical orientation of Ladakh is very different from that of Upper Tibet, we term this era the ‘imperial and post-imperial period’ (see Bruneau and Bellezza forthcoming).

Fig. 23. The inner and outer entrances to the main edifice and parts of all four chambers of the second level are visible.

Fig. 24. Gyapa Jo Khar from the east. From this perspective the extremely prominent revetment underpinning the main edifice and lhatho are unmistakable.

Fig. 25. Gyapa Jo Khar from the north. Note how the revetment and lhatho narrow to less than 3 m in width. The lhatho is the principal village shrine for Tsebla, the territorial god of Nyarma.

The main entranceway of Gyapa Jo Khar is elevated 2 m higher than the floor level of the west wing. The main edifice sits upon a high revetment, which attains a maximum height of 5 m on the east and north sides. The main entranceway accesses the four small chambers of the second level, three of which have much of their corbelled stone roof intact. The first room entered (4.3 m x 1 m) is long and narrow; it is an anteroom or vestibule that must have had a non-residential function. In the rear of this room there is another large entrance (1.8 m x 1.1 m) with a stone lintel, leading to three small chambers, the east one of which has a steeply inclined floor and is bereft of its roof. The size of these chambers and the inclined floor seem to indicate that these rooms had an ancillary or utilitarian function such as storage or possibly cooking.

To the rear or north of the aforementioned four chambers one can easily climb to the roof of the structure. At one time this open-air space of the third level of the main edifice may have been enclosed partially or fully by walls linking the four chambers of the second level with the D-shaped structure at the rear of the installation. Although almost nothing of the original D-shaped structure still stands, the contours of the revetment upon which it was placed can be traced. The remains of an ancient wall, which is now integrated into the lhatho shrine, does indeed indicate that a substantial residential structure once occupied the same space. The roof of this no longer existing building constituted the fourth level of the main edifice. Although free-standing structural evidence for the third and four levels of the main edifice is very limited, most of the living space of the installation may have been situated there. Given the extent of its plan, the main edifice could have contained a total of two or three times the total interior area of the four small chambers of the second level.

The lhatho now standing on the highest point of the site is built of mud bricks. Its construction supplanted the original structure of the palace long before living memory. A solid and simply built structure, the architectonics of the lhatho are far more rudimentary than those of Gyapa Jo Khar. The lhatho serves as a shrine for the territorial god (yul-lha) of Nyar-ma. This deity in the local dialect is called Tsebla (Rtse-bla), an Old Tibetan rendering of the Classical Tibetan Tselha (Rtse-lha). As a class of deities, tselha are the protectors of castles and the insurers of military victories as well personal protective spirits. The manner in which the name of this archaic group of spirits is locally pronounced may indicate a very long association with Gyapa Jo Khar.

At the base of the spur on which Gyapa Jo Khar sits is a boulder with a large rock carving, consisting of three anthropomorphic figures. Unfortunately, this carving is now very faint and is hardly visible from most angles. A large central figure is flanked by two smaller figures, all of which wear a long dress or robe. The middle and right figures are depicted with deeply flexed arms. According to the local tradition, these three figures represent the Tshelha Namsum (Tshe-lha rnam-gsum), a trinity of long-life deities consisting of Tshepakme (Tshe-dpag-med), Drolkar (Sgrol-dkar) and Namgyalma (Rnam-rgyal-ma). However, I cannot recognize any of these deities and suggest that other Buddhist gods (such as Bodhisattvas) are portrayed in the rock carving. The general aspect of the figures strongly suggests that the carving was created before the 11th century CE.

Dorje Chenmo Chapel of Nyarma

Quentin Devers introduced us to site of the Dorje Chenmo (Rdo-rje chen-mo) temple (lha-khang) and the rock shelters located there. In the Ladakh oral tradition, it is widely held that this hilltop Buddhist site was chosen by Lotsawa Rinchen Sangpo for enshrining his kordak (dkor-bdag), the protector of the monasteries and religious properties he established. This protector is the goddess Dorje Chenmo. The isolated and lofty location of the facility is in keeping with those customarily used to establish protector shrines and chapels. According to the middle length biography of Lotsawa Rinchen, this great saint founded and consecrated the Buddhist temples of Nyarma in Mar-yul (old name of Ladakh), Khachar (Khwa-char) in Purang (Pu-hrang) and Tholing (Mtho-lding) in Guge (Gu-ge) on the very same day.*

* I wish to thank Tashi Tsering of the Amnye Machen Institute for recently supplying me with a number of documents needed in the historical study of Ladakh.

The Dorje Chenmo temple stands aloof from the large monastic facility in the valley below. Both, as already noted, lie in a state of ruin. The walls of the Dorje Chenmo chapel have been preserved to a height of 3 m or 4 m, allowing for a good assessment of its plan. The temple (6 m x 7 m) consists of a cella flanked on the west or forward side by a vestibule and on the south side by a narrow room elevated approximately 1.2 m above the rest of the chapel. The function of this elevated room is not clear. It was possibly used to enshrine objects as part of the cult of Tibetan Buddhist protective deities. The exterior entrance leading to the vestibule is unusually small (1 m x 60 cm). The entrance from the vestibule to the main sanctum is somewhat larger (1.2 m x 80 cm). Both of these entrance have intact stone lintels, as Devers noted (the only temples documented in Ladakh to possess this feature; see Devers forthcoming). Small doorways are a distinctive trait of Buddhist temples founded in the 11th and 12th centuries CE, but those of the Dorje Chenmo temple are particularly tiny. As Devers commented in his article above, while the main sanctum could only have supported a roof made of wood, the rooms flanking it may have used corbels in a hybrid arrangement.

The use of stone members, windowless stone walls, an organization of internal space sequestering the cella, as well as the tiny doorways of the Dorje Chenmo chapel, could support the oral tradition surrounding it suggesting a turn-of-the-second millennium CE foundation date. However, Devers (forthcoming) believes these architectural features as well as the remote hilltop location, indicate that the so-called Dorje Chenmo temple was built at an earlier date.

As first, I was swayed by the oral tradition attached to the Dorje Chenmo temple, but after reading Devers’ papers and discussing the matter with him, I think he may be correct regarding the chronology of the site. Thus it appears he has made a great discovery, adding a significant new chapter to historical researches in Ladakh.

Devers (ibid.) examines carved Buddhist stelae from the Nyarma region, some of which certainly predate the 11th century, clear proof of an earlier Buddhist presence in the region. Devers (ibid.) also refers to a pair of temples located just north of Nyarma, with similar constructional and geographical features to the Dorje Chenmo temple. For him, these temples and stelae are part of an interrelated Buddhist architectural and artistic tradition that existed in central and upper Ladakh before the time of Lotsawa Rinchen Sangpo. Seen in this light, the Lotsawa simply reoccupied and probably reconsecrated the site of what became his Dorje Chenmo temple.

The proliferation of carved Buddhist stelae from the imperial and post-imperial periods (650–1000 CE) certainly indicates that Buddhism of the Kashmiri or Dardic type was established as far west as Upper Ladakh. As seen in Kargil and Lower Ladakh, some stelae may be somewhat older than the Tibetan imperial period. This may also possibly be true of one stele from Nyarma illustrated second from the right in photographs of stelae (see Devers forthcoming). With the coming of the Tibetan imperial armies and imperial administration in the 7th century CE, and especially after the late 8th century CE, another cultural impetus for the spread of Buddhism appeared from the east to mix with and be enriched by the preexisting Indo-Iranic variety. Thus, it is not unreasonable to assume that there were Buddhist temples in Upper Ladakh before the second diffusion of Buddhism, small, rudimentary affairs like the Dorje Chenmo chapel. These temples were probably used in cult practices connected to Mahayana and possibly tantric Buddhism (worship of Bodhisattvas, the mystic Buddha and protective deities). The miniature size of Nyarma and the two neighboring temples indicates that a fully developed tradition of monasticism probably had not taken root in Upper Ladakh in that period.

The lack of carved mani stones at the Dorje Chenmo site also supports a pre-11th century CE foundation of the site. At least in Upper Tibet, with the coming of the second diffusion of Buddhism, mani stones found great expression and appeared in small or large numbers at virtually all temple and monastic sites. Stones inscribed with prayers before this period are very rare (see April 2011 issue of Flight of the Khyung).

Surmounting the three walls circumvallating the forward side and flanks of the Dorje Chenmo hilltop are small pyramidal extensions. Although there is no sign that they contained consecrated objects, these merlons appear to represent chortens. While I cannot speak for Ladakh, in Guge there are at least two sites with the same style structures but of a larger magnitude. These Buddhist facilities appear to have been founded circa the 11th century CE (I have the names, coordinates and pictures of these interesting sites in my archives but they are not immediately accessible). If the chronology we ascribe to these Buddhist sites is accurate, it suggests that parapet walls with chortens was an architectural trait that diffused from Ladakh to western Tibet. I hasten to add that the chronology of sites featured in this newsletter is based on typological and stylistic methodologies. It is essential that chronometric testing of these structures is carried out to either confirm or invalidate this dating.

The cells mentioned by Devers in his article above are situated on the east side of the Dorje Chenmo hilltop. No more than a dozen individuals could have been comfortably sheltered in these cells. The cloisters at the Dorje Chenmo temple may have housed native monks, but they could also have been shelters for caretakers, lay ritualists, or itinerant monks from Indo-Iranic regions to the west. There are three or four low-lying structures containing the tiny cells (around 4 m² each):

South structure: two chambers linked by an interclose. Both chambers have exterior entrances. There is a parapet wall on part of the roof. The corbelled roof over the interclose is intact.

Central East and Northeast structure(s): Much of the building has been levelled but wall fragments of up to 1.5 m in height have survived. No structural evidence for the roof is extant.

North structure: A multi-roomed building. The tiny northeast chamber has some of its corbelled roof intact. There are a few in situ corbels on other walls as well. A wall buttress typical of corbelled architecture, situated between the northeast and northwest chambers, also indicates that this building had a stone roof.

The three or four outbuildings are of rudimentary construction, relying on a elementary corbelling technique. As seen in Devers photographs (figs. 8, 11), the corbelling technique used in Gyapa Jo Khar is far more ambitious and sophisticated than that of the Dorje Chenmo cells. It is also applied to a much larger and more elaborate building. The corbelling of the Dorje Chenmo site must have been directly inspired by the architecture of Gyapa Jo Khar. However, it represents a later and less adept adaptation of this building technique. It would appear that by the post-imperial period (850–1000 CE), the skill and resources needed to construct such castles had disappeared and was replaced by an eminently practical derivative, but one that suggests an overall degradation of the tradition of architectonics in Ladakh.

In Upper Tibet there are few demonstrable examples of corbelled architecture after the 11th century. I have already mentioned Yama Chorten. To this site can probably be added the corbelled chortens of Dechoe (Sde-chos), in Ruthok (see December 2010 issue of Flight of the Khyung). The corbelling of these two sites is on a scale far less ambitious than that presented by the archaic fortresses and temples of Upper Tibet.

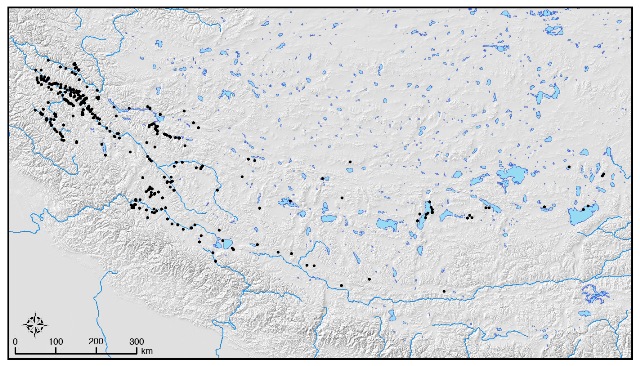

Fig. 33. Map of hilltop strongholds documented in Ladakh and Upper Tibet before Martin Vernier, Quentin Devers and John V. Bellezza began their survey work. Map by Quentin Devers.

Fig. 34. Map of the hilltop strongholds in Ladakh and Upper Tibet including those documented in the survey work of Martin Vernier, Quentin Devers and John V. Bellezza. Map by Quentin Devers.

Gyapa Jo Khar and the historical signification of the term Zhang Zhung

Introduction

This article touches upon outstanding historical issues relevant to the chronology and cultural complexion of Gyapa Jo Khar. It also examines Zhang Zhang in a multidimensional fashion, taking into account the historical, archaeological and anthropological facets of this politically, culturally and linguistically laden term. This comprehensive review of the semantics connected to Zhang Zhung serves to chart the evolving geographical and historical identity of this designation. As I am unable to attend the International Association of Tibetan Studies conference in Ulan Bator this July, this article has been written in spirit for it.

If Gyapa Jo Khar was built after circa 650 CE, it can readily be seen as part of the process of the Tibetan linguistic and cultural transformation of Ladakh. This Tibetanization occurred with the imperial conquest and annexation of Ladakh. Seen in this perspective, the introduction of stone corbelling techniques into Tibet would have been effected by Upper Tibetans of Zhang Zhung, who, along with their military and administrative impedimenta, carried their architectonics to Ladakh.

However, if Gyapa Jo Khar was constructed before the 7th century CE, as is possible, the historical factors responsible for its creation become a good deal murkier. Historical sources state that until the mid-7th century, an independent kingdom known as Zhang Zhung existed in western Tibet. The Old Tibetan Chronicle and Old Tibetan Annals, studied by Geza Uray (1972b), H. E. Richardson (1998), Brandon Dotson (2009) among others, furnish the oldest and most accurate accounts of the fall of Zhang Zhung. Unfortunately, these texts tell us nothing about the historical genesis of the Zhang Zhung kingdom.

Zhang Zhung, Upper Tibet and Ladakh of Old Tibetan literature

Zhang Zhung was once a kingdom that existed in Upper Tibet. According to the Old Tibetan Chronicle, Zhang Zhung suffered a partial defeat at the hands of Khyungpo Pungse Zutse (Khyung-po spung-sad zu-tse), one of the key ministers of the Tibetan King Namri Löntsen, probably in the 610s or 620s CE (Richardson 1977: 13; Dotson 2009: 17; Uray 1972b: 40). This minister had defected from Zhang Zhung to join the Central Tibetans (ibid.). According to the Old Tibetan Chronicle and Old Tibetan Annals, circa 644 CE, the next Tibetan King, Songtsen Gampo (Srong-brtsan sgam-po), brought about the complete subjugation of Zhang Zhung by assassinating its king, Liknyashur (Lig-snya-shur). Thus, in these Old Tibetan language documents, Zhang Zhung denotes a kingdom that can be traced to the period not long before and during its defeat at the hands of the Purgyal (Spu-rgyal) dynasty of Central Tibet.

The Chinese geographic work Taiping huanyu ji, completed in 983 CE, states that Zhang Zhung (Yangtong) was conquered by the Tibetans in 649 CE, leading to much destruction and the scattering of her people (Zeisler 2009-2010: 403, 404, after Pelliot 1963). Of course, Chinese sources such as this serve as independent corroboration of Tibetan historical materials.

In the Old Tibetan Chronicle, we find ‘Tise the Mountain’ and ‘Mapang the Lake’. These very prominent sacred topographical features in southwestern Tibet are mentioned in an allegory of shifting ministerial alliances (Beckwith 1987; Bacot et al. 1940-1946; Richardson 1998). The protagonist in this tale is Khyungpo Pungse Zutse, conveying that Ti-se and Ma-pang were prizes or emblems of the Zhang Zhung kingdom won by the Tibetans. In the Dunhuang chronicle fragment (Pt 1286), another Upper Tibetan region known as Darpa (Dar-pa) is connected to Lord Liknyashur. A localization in western Tibet for Darpa can be inferred, for we know that Liknyashur had his headquarters at Khyunglung Ngulkhar (Khyung-lung rngul-mkhar). That this castle is situated in Upper Tibet is corroborated in the Old Tibetan Chronicle, in the tale of the disaffected wife of King Likmyihya (Lig-myi rhya, sic), Semarkar (Sad-mar-kar), who leaves Khyunglung Ngulkhar to go fishing at Lake Ma-pang (Uray 1972a), presumably the closest freshwater lake. This capital of political Zhang Zhung can probably be identified with Khardong (Mkhar-gdong), a ruined fortress near the Bon monastery of Gurgyam (Bellezza 2002: 37–39; 2011a: 74, 75; September 2012 Flight of the Khyung). Therefore, from the Old Tibetan manuscripts cited above, we can conclude that beginning in the early 7th century, Zhang Zhung designated at minimum a western section of Upper Tibet (the precise extent of its territory is unknown). The capitol Khyunglung Ngulkhar is also cited in Dunhuang documents Pt 1051 and Pt 1052, but these are divination texts that do not furnish hard geographic or political data.

The Old Tibetan Chronicle states that after the conquest of Zhang Zhung, Khyunglung Ngulkhar was the residence of administrative chiefs from Central Tibet (Uray 1972b: 41, 42, 44). After its subjugation, Zhang Zhung and the other highland kingdom of ancient Tibet, Sumpa, were organized into administrative and military units know as tongde (stong-sde). Each tongde consisted of 1000 residential camps. The Old Tibetan Annals states that Zhang Zhung was divided into lower (smad) and upper (stod) halves, each with five tongde (Dotson 2009: 39, 41).

According to Petech (1977: 10), Baltistan was conquered by the Tibetans circa 720 CE, therefore, the Tibetan occupation of Ladakh must have come somewhat earlier. Petech (ibid.) believes, nonetheless, that the Tibetanization of Ladakh did not begin until after circa 900 CE. In my opinion, his chronology of the linguistic and cultural integration of Ladakh into Tibet appears to be too late. The wealth of Old Tibetan language inscriptions in Ladakh, as collected by Tsuguhito Takeuchi, Giuseppe Tucci, and others, indicate that this process (through widespread visitation of Tibetans of military rank) began no later than the 8th century CE. Moreover, pre-existing cultural ties between Upper Ladakh and Upper Tibet, as explicated in this article, would have facilitated the process of Tibetanization.

Tibetanization initiated before the 9th century CE is also supported by Denwood (2005) on linguistic grounds, who states that the initial letter clusters in Ladakhi and Balti may preserve a stage in the linguistic development of archaic Tibetan languages that even predates the earliest examples of the Tibetan script. Furthermore, Zeisler (2005) considers that the archaic dialects of the west and those of Amdo probably formed a linguistic continuum in the time when Old Tibetan was spoken in the Changthang. Zeisler (ibid.) observes that initial clusters had disappeared from the central Tibetan dialects by the beginning of the 9th century CE, as inferred from Chinese renderings of Tibetan names. That the Ladakhis and Baltis retained these clusters suggests that they began adopting the Tibetan language as early as the 7th century CE, embracing its old-fashioned phonological structures. Likewise, Uray (1990: 217) is of the opinion that Tibetan was spoken in Ladakh in the 7th century CE.

Prior to the 7th century CE, the linguistic composition of Ladakh is unclear. Perhaps Zhang Zhung or closely allied languages were used in the upper portion. A group of languages that appear to be related to Zhang Zhung are still spoken in Kinnaur, Lahoul, Kullu, and in border areas of Uttarakhand (for more information, see van Driem 2001; Matisoff 2001; Jacques 2009).

The extent of the Zhang Zhung kingdom before its downfall and whether it included Ladakh remains a moot point. Scholars such as Philip Denwood (2005; 2008) believe that little if any of Ladakh was part of the Zhang Zhung kingdom. A crucial piece of evidence supporting his position is the registering of able-bodied men in both Zhang Zhung and Mar (Mard / Mar-yul, the old name for Ladakh), in the entry of 719 CE of the Old Tibetan Annals (Dotson 2009: 111; Uray 1990: 218). Thus, according to this source, these two countries were clearly distinguished from one another. Nevertheless, how Zhang Zhung and Mard differed from each other vis-à-vis their political positions in the Tibetan empire is unclear. It is possible that Zhang Zhung and Mard in the Old Tibetan Annals refers to two traditional territories or erstwhile kingdoms, and is not the nomenclature of political divisions of the Tibetan empire.

Bettina Zeisler (2010-2011) for her part, holds that all Ladakh was part of Zhang Zhung in the imperial period. Zeisler (ibid.) is of the opinion that upper Zhang Zhung of Tibetan sources and Lesser Yangtong of Chinese sources not only included Lower Ladakh, but also Baltistan, Gilgit and Hunza all the way to the Pamirs. This possible consolidation of non-Tibetan regions into the Zhang Zhung of the empire makes sense strategically. It could have acted as a political and economic incentive to the inhabitants of Zhang Zhung to focus their military attention westwards and not eastwards. Zhang Zhung did in fact mount a rebellion against her imperial masters in 677 CE (Beckwith 1987: 43; Dotson 2009: 92). This suggests that such an imperial political calculation may have been needed to keep the people of Zhang Zhung pacified. We have to keep in mind that many inhabitants of Zhang Zhung were pastoral and semi-nomadic in character, keen horsemen and warriors on the lookout for plunder wherever it could be found.

For Zeisler (ibid.), lower Zhang Zhung and Greater Yangtong designate Upper Ladakh, western Tibet and a portion of the Changthang. A key piece of evidence used by Zeisler to make her determination is the list of the five districts (stong-sde) of upper Zhang Zhung and the five districts of lower Zhang Zhung in the 16th century CE Mkhas pa’i dga’ ston (ibid., 390–392). Although I translated this list as well as the one in the 13th century CE Mkhas pa’i ldeu (2008: 271; 2011a: 58, 59), the Turkic or Iranic origins of the term bag / bag-ga had escaped me. This word element is found in the names of all five districts of upper Zhang Zhung, supporting the position that these places may have been situated in Indo-Iranic or Turkic territories bordering the Tibetan plateau. Conversely, the names of the five districts of lower Zhang Zhung seem to be regions in Upper Tibet and adjoining Spiti. Nonetheless, the biggest obstacle to reading the ten districts of Zhang Zhung in this widely embracing manner is that Ladakh (Mar-yul) is not explicitly mentioned, or if it is, it is by another name.

The ten districts of Zhang Zhung in Classical Tibetan literature is derived from an imperial period conception of the extent of Zhang Zhung. This classification of the districts is political and administrative in nature. It serves to illustrate how some of the imperial holdings were organized under King Songtsen Gampo (other Tibetan regions are also delineated in this literature). In the Old Tibetan historical references noted above, Zhang Zhung and the places within it occur in a period just before and after the kingdom’s downfall, perhaps before the administrative structures that gave rise to the ten districts could be created. A slightly earlier milieu seems to explain the more restrictive geographic purview of Zhang Zhung in Old Tibetan literature. Hence, the wide territorial scope of Zhang Zhung proposed by Zeisler does not necessarily contradict the smaller area settled upon by Denwood.

We know from Old Tibetan historical sources that a sovereign Zhang Zhung kingdom existed by the early 7th century CE and met its demise in the 640s CE. That it could suffer a major provocation indicates some degree of additional historical depth measured in decades, if not centuries, but nowhere is this made manifest in Old Tibetan literature. In any case, the historical legacy of Zhang Zhung had both pre-conquest and conquest phases, possibly furnishing a historical footing for the varied application of Zhang Zhung / Yangtong in Tibetan and Chinese writings. As we shall see, there are also cultural and archaeological dimensions to Zhang Zhung that must be carefully considered in any broad assessment of the term.

As Devers observed in his article above, the creation of Gyapa Jo Khar may have been due to political factors and the regional balancing of power. If he is right, the size and nature of the Zhang Zhung polity before the start of the Tibetan imperium may be of critical importance in determining its political affiliations. Subscribing to Devers’ political hypothesis, however, sill begs the question as to the nature of political relations. At this juncture we cannot confirm that Ladakh was an integral part of the Zhang Zhung kingdom (as some Bon sources would have us believe), or a vassal, an ally, a suzerain, a confederate, or completely independent?

The best known Bon claim that Ladakh was a constituent part of the Zhang Zhung kingdom comes from the Ti se’i dkar chag, written by Karu Drupang (Dkar-ru grub-dbang) in the first half of the 19th century CE (see Bellezza 2011a: 83, 87, 88). In this account, one of the 18 kings of Zhang Zhung was based in Ladakh. This king, named Nyelo Werya (Nye-lo wer-ya), is said to have had a crown of bird horns (bya-ru) made from meteoric iron (gnam-lcags). The validity of this account, however, is difficult to gauge, as it is late in origin and not readily attributable to older sources. Furthermore, it was composed as part of a resurgence in Bonpo interest in Zhang Zhung (which has continued to the present day). Thus Ti se’i dkar chag may have embellished history in a variety of ways for its own purposes. Unmistakably, an embellishment is recognizable in its antiquation of the tradition of monastic discipline (’dul-ba). Still, the reality of a Zhang Zhung king of Ladakh cannot be dismissed out of hand. This is more so true if we take the Ti se’i dkar chag account as a metaphor for prehistoric cultural interconnections between Upper Tibet and Ladakh. Other royal capitols of Zhang Zhung cataloged in the text are associated with significant concentrations of archaic residential and ceremonial monuments, demonstrating that these sites had a well-developed cultural substructure before the imperial period (Bellezza 2011a).

The political aspects we have been reviewing notwithstanding, I am inclined to see Gyapa Jo Khar as reflecting the diffusion of archaic cultural traditions between Upper Tibet and Ladakh. In addition to a political Zhang Zhung, one may speak of a linguistic Zhang Zhung and a cultural Zhang Zhung, and possibly an ethnic Zhang Zhung as well. These various aspects of Zhang Zhung need not have occupied exactly the same territory or existed precisely at the same time.

Pt 1060, an Old Tibetan text probably written in the 8th or 9th century CE, expounds upon the ancestral lineages of the horses used in archaic funerary rites. This text is not a historical document per se, it belongs to a body of archaic funerary ritual works. While it is set in the first half of the 7th century CE, its lineages of psychopomp horses are understood to be of considerable antiquity. In Pt 1060, two Zhang Zhung gods are mentioned in conjunction with King Liknyashur and his castle, Khyunglung Ngulkhar, situated in the headwaters region around Mount Tise, in southwestern Tibet (Bellezza 2008: 522, 523). The subjects of this king are stated to be the people of Guge and Gugchok (Gug-lchog, probably present-day Rong-chung and Chu-gsum; cf. Hazod 2009: 168). This is added evidence for the political heart of Zhang Zhung in the 7th century CE being in western Tibet, corroborating geographic indications provided in Old Tibetan historical texts. Pt 1060, however, augments the geographic compass of Zhang Zhung to include Gugchok, which appears to be the badlands region immediately west of Guge and bordering on Spiti and Kinnaur.

The same headwaters region, as well as Guge, are also noted in one of the origins myths of Pt 1136, another funerary text probably of the 8th or 9th century CE (Bellezza 2010: 38, 39; 2008: 526). Such proclamations of mythic origins (smrang) in Old Tibetan ritual literature are often overtly set in primal or early times, allegorical and legendary affirmation of the great age and legitimacy of the funerary rites. No mention of Zhang Zhung is made in Pt 1136, nor in other archaic funerary texts of Dunhuang, except for Pt 1060.

As we have seen, in the Old Tibetan Chronicle and Old Tibetan Annals, Zhang Zhung is not expressly associated with a pre-7th century CE antiquity. The designation for prehistoric regions of Upper Tibet in Old Tibetan ritual literature comes under a different rubric. Four regions in Old Tibetan documents are specifically connected to early Upper Tibet (Bellezza 2010: 59, 67–70). One is Mayul Thangye (Smra-yul thang-brgyad), a pastoral region with ancestral cultural connotations, which is also mentioned in Bon documents. Two others are Changdrok Namstoe (Byang-’brog snam-stod) and Changkha Namgye (Byang-kha snam-brgyad), the realm of wild yaks and other quarry of hunters in the far north. The fourth region localized in Upper Tibet is Dga’-yul byang-nams of Pt 1136 (Bellezza: 2008: 518, 520, 521), which is also identified with the ancestral afterlife in other texts and thus of great antiquity. These regions, as the geographic backdrop of archetypal myths, are in contradistinction to Zhang Zhung with its 7th to 9th century CE political connotations in Old Tibetan historical documents. The tribal groups associated with Dga’-yul byang-nams in Pt 1136 are Mra (Smra) and Ma (Rma). Smra is the tribal appellation of Zhang Zhung, according to a wealth of later Tibetan sources (such as the La dwags rgyal rabs). Ergo, there can be no question that Smra and Zhang Zhung refer to the same territory or thereabouts. In Old Tibetan documents, Smra is both a tribal epithet of regions of Upper Tibet (man of Smra = Smra-myi in Pt 1136; priest of Smra = Smra-bon in Pt 1136 and Pt 1285) and the name of an Upper Tibetan country of the same tribe (Smra-yul in Pt 1285, ITJ 731, ITJ 739, and in Byol rabs of the Gathang Bumpa documents).

While Zhang Zhung is not literally equated with regions of prehistoric Upper Tibet in the archaic ritual manuscripts of Dunhuang, it is in another Old Tibetan text. This text, Rnel dri ’dul ba’i thabs sogs, belongs to the Gathang Bumpa collection of documents recently discovered in southern Tibet, and is best dated to circa 850–1000 CE (Bellezza 2010; 2013). Rnel dri ’dul ba’i thabs sogs boasts a number or origins myths set in the distant past. In one of these tales, Zhang Zhung is explicitly tied to Tsho Muleö (Mtsho mu-le Ōd), which, as we know from Bonpo sources, denotes Lake La Ngak (or possibly Lake Mapang) in southwestern Tibet (Bellezza 2013: 173, 174). This is the oldest known textual reference to Zhang Zhung as a designation for areas of prehistoric Upper Tibet. This document, written roughly 1100 years ago, set the historical precedent for Zhang Zhung being conferred with expansive chronological semantics by the Bon religion beginning around 1000 CE.

As we now know, depending on the Tibetan literary genre, the term Zhang Zhung has various components of chronological and geographic signification. In Old Tibetan historical literature, Zhang Zhung denotes places in western Tibet from circa the 610s CE through much of the imperial period, while in Bon literature it is tantamount to a much larger territory envisioned as having existed for millennia. Again, the historical bridge between these disparate notions is a text from Gathang Bumpa. This variability in the meaning of the term Zhang Zhung appears to be a major factor in explaining why considerable confusion over its application has arisen in Tibetology.

Zhang Zhung, Upper Tibet and Ladakh of the archaeological and anthropological records

Now let us turn to the archaeological evidence to gain a fuller understanding of the import and use of the term Zhang Zhung. There are three types of highly distinctive funerary monuments in Upper Tibet: walled-in pillars, arrays of pillars appended to temple-tombs, and mountaintop cubic tombs (Bellezza 2008; 2011; 2011a). Chronometric and other archaeological evidence acquired thus far suggests that the pillar monuments may have originated in the first third of the first millennium BCE and continued to be built until the advent of the imperial period in the mid-7th century CE. These monuments circumscribe the geographic bounds of a unique paleoculture (stress on its antiquity) or archaeological culture (stress on its material form).

From many years of survey work, I know that the geographic distribution of the groups of pillars and cubic tombs demarcates a specific area in Upper Tibet. The range of the walled-in and appended pillar monuments extends from Khyunglung and Ruthok in the west to Namru (Gnam-ru) in the east, a distance of 900 kms as the crow flies. The mountaintop cubic tombs are distributed in western Tibet and the western Changthang only. Elaborate funerary monuments are a integral and significant part of any culture that built them. Thus, the hallmark pillars and tombs are ideal markers for defining the size of the largest archaeological culture in Upper Tibet. In order to augment our analysis, this core or principal paleocultural entity of Upper Tibet can be correlated to the variable Tibetan literary record pertaining to Zhang Zhung.

A wide spectrum of Tibetan literary sources, including the Old Tibetan historical documents mentioned above, not only places Guge in Zhang Zhung, but even as its central region in certain instances. While, sui generis pillars and tombs are not found in most of Guge, cultural links between it and the core Upper Tibetan paleocultural region are indicated all the same. It is the badlands portion of Guge that is without these pillars and cubic tombs, and their absence may be due to topographic and geological considerations. Moreover, the ancient capital of political Zhang Zhung, Khyunglung Ngulkhar, in as much as it can be identified with the site of Khardong, straddled the physiographic divide between the badlands and high plateau. Guge possessed a tradition of rock art very similar to other parts of Upper Tibet, as well as all-stone corbelled buildings and lone stelae. These archaeological monuments and art indicate that Guge was closely related to the core paleocultural region of Upper Tibet. In his religious history (bstan-’byung), the renowned Bon scholar Lopon Tenzin Namdak observes that Guge was somehow partitioned from the rest of the prehistoric kingdom in a rather minor way. For his appraisal, Lopon Tenzin Namdak relies upon Khro bo dbang chen ngo mtshar, a volume written by Kyabkyi Tonpa Rinchen (Skyabs kyi ston-pa rin-chen ’od zer, born in 1353 CE). Here we have excellent correspondence between the archaeological and the textual data (Bellezza 2011a: 61, 62, 68).

We might therefore call Guge a collateral zone of the Upper Tibetan paleocultural region. Changthang regions east of the 88th meridian can also be characterized as a collateral zone of the main Upper Tibetan archaeological culture. This tract between western Namru and Lake Nam Tsho (Gnam-mtsho) and Nakchu (Nag-chu) has isolated pillars. Its rock art exhibits many similarities with the rock art of the core region but with the admixture of unique genres of depiction. This eastern region however does not have the same types of all-stone corbelled buildings. Thus from an archaeological perspective, it appears to have been more culturally removed from the core paleocultural entity than Guge.

Like the overall size of Zhang Zhung, the extent of its eastern borders are not spelled out in Old Tibetan literature. Analyzing textual materials, I attribute the eastern collateral zone to another proto-tribal region of Upper Tibet, Sumpa (see 2002: 10; 2011a: passim). According to Bon texts, Zhang Zhung and Sumpa shared many political and cultural elements in common.

For the purposes of archaeological study, can we call the principal paleocultural entity of Upper Tibet as well as its collateral areas Zhang Zhung? I think we can, for as we know, this label has been affixed to prehistoric Upper Tibetan regions for around 1100 years. That is an ancient tradition by any standard and one that archaeologists and others can borrow upon without reservation. Nevertheless, as this article shows, when fastening the Zhang Zhung label to archaeological materials it is important to articulate what criteria are being used. It must be disclosed whether this term has a textual, archaeological, anthropological or linguistic basis, as well as the specific region to which it is affixed.

The question now remains: Was Ladakh part of Zhang Zhung in an archaeological sense? Upper Ladakh, as we know, had corbelled architecture, some of which may predate the 7th century CE. However, this region is devoid of funerary pillars and mountaintop cubic tombs, essential evidence in determining the composition of its ancient culture. This evidence indicates that in the sphere of funerary traditions there was considerable variation between Upper Tibet and Upper Ladakh. Nevertheless, Upper Ladakh does share rock art in common with Upper Tibet. In a study of rock art links between Upper Ladakh and Upper Tibet, we call this shared artistic heritage the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau’ Style (see Bruneau and Bellezza forthcoming). This body of analogous rock art spans the late Bronze Age to the imperial period, indicating that cultural ties between Ladakh and Upper Tibet were extremely well grounded. Nevertheless, the WTPS makes up less than 20% of the total rock tableaux of Upper Ladakh and Upper Tibet (in Zanskar less than 10% of rock art is in the WTPS). The remainder of this art is in alternative styles, reflecting differing cultural sources and lines of historical development.

Perhaps even more crucial than cognate rock art, are the ceramic assemblages recovered from tombs in western Tibet and Upper Ladakh bearing vivid technical and stylistic similarities. These links appear to be more vigorous between Upper Tibet and Ladakh, than between the former and adjoining non-plateau regions. The common ceramics include large amphorae with round bottoms and tapering sides, each with a pair of lug handles. There are also vessels with wider bulbous bottoms and lug handles. The ceramic vessels in both regions are predominantly unglazed redware.* For this assessment of Ladakh ceramics, I have relied on a b&w photograph published in A. H. Francke’s Antiquities of Indian Tibet, vol. 1 (pl. XXVIIIa). According to Francke (ibid., pp. 64, 65), the ceramic vessels in this photograph come from Dard graves in the village of Gya, which are called Mon gyi rom-khang. Found inside these large earthen chambers were pinewood boards upon which skulls were placed. Francke (ibid.) notes that similar tombs were surveyed in the Leh region, some of which have ceramic vessels full of bones. He dates these tombs to the ‘Empire of Eastern Women’, an ambiguous attribution based on Chinese literary sources (Dongnüguo). What the historical relationship between the Dards and the Empire of Eastern Women was, if any, is still unclear. Moreover, the tombs Francke claims are Dardic carry the name of the Mon, another nebulous early cultural-ethnic group of Ladakh. Prehistoric tombs, stelae and corbelled buildings in Upper Tibet are often attributed to the Mon. In the common parlance of Upper Tibet, the ethnonym Mon comprises the prehistoric native population augmented by settlers (a ruling elite?) coming from the north and west. For example, Mar lung pa rnam thar records that after being pushed out of northern regions by the Hor (probably a Turco-Mongolian group), the Mon settled in the southwestern portion of Tibet (Bellezza 2011). The cultural/ethnic groups reviewed in the context of this paragraph, however, are all vague and remain unconfirmed archaeologically speaking.

* Color of pottery uncertain in photograph. For the ceramics of western Tibet, see Chinese Institute of Tibetology 2001; Yao Jun 2004; Flight of the Khyung, October 2010 and April 2012. Organic materials recovered from the same tombs as the ceramic finds have yielded calibrated dates of circa 500 BCE–300 CE (ibid.). It is this timeframe in which the tombs of Mon gyi rom-khang are likely to belong. A detailed typological and comparative study of ceramics in Ladakh and Upper Tibet is certainly the order of the day, if we are to better comprehend the cultural interactions between the two regions. Petech (1977: 5) refutes the idea that a Mon population predated the Dardic one in Ladakh, but this may not be correct. That cis-Himalayan peoples (generically called Mon) may have crossed into Ladakh in prehistoric times remains a distinct possibility. The Mon and particularly the Kelmon (Bskal-mon), of Upper Tibetan folklore, are attributed to sites that date back as far as the first millennium BCE. Also, Petech’s notion (ibid.) that the toponym Mar comes from the smar of Zhang Zhung smar of Bon tradition, as well as Smra Zhang Zhung of Tibetan documents, is rather confused. In the Zhang Zhung language, mar means gold, while smar is glossed ‘goodness’ or ‘auspiciousness’. In the Bon tradition, Zhang Zhung smar is an epithet referring to the salutary nature of Zhang Zhung, as the source of most Bon scriptures and traditions. Smar is also the name given to the Zhang Zhung language and its putative script by the Bonpo. As already explained, Smra is the tribal appellation of Zhang Zhung. That mar, smar and Smra are terms with different ranges of signification and should not be confounded is also understood by Uray (1990: 217, 218). This does not discount Denwood’s position (2005: 37) that all three words are etymologically interrelated. This remains a distinct possibility, but it is a matter best taken up by historical linguists.