July 2013

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another breathtaking Flight of the Khyung, a source for all that is noble and ancient in Tibet! As promised, this month’s focus is on the lovely polychrome rock art of highland Tibet. We will also probe the Neolithic in Upper Tibet, pointing towards substantial discoveries that could be just around the corner.

Adding a little color to things: The polychrome rock art of Upper Tibet

For ages, artists have known that colors touch the soul, invoking moods ranging from the somber to the ecstatic. In the historic era, Tibetan artists have enthusiastically applied a multitude of colors to their religious paintings, interior decorations, textiles, furniture, and a host of other objects. A multicolored palette was also taken up by the makers of rock art in Upper Tibet. Although uncommon, pictographs painted in two or more colors are indeed known in the region.

In the eastern and central Changthang, a handful of pictographs painted in three or four colors have come to light. This polychrome art was made using different mineral pigments including red ochre, yellow ochre, and white (lime?) and blue-grey colorants. These pigments were applied to limestone cliffs and caves. While monochrome pictographs abound in the Changthang, makers of rock art used two or more colors sparingly. This may have been a matter of painters not often having various pigments at their disposal, or they may simply have been disinclined to invest so much effort in their art. Be that as it may, the sourcing of more than one pigment would have added to the time demands of crafting rock art.

Polychromy in Upper Tibetan rock art is not a particularly ancient tradition. No pictographs of more than two colors dating before early historic period (650–1000 CE) have been positively identified. Moreover, there is no zoomorphic or anthropomorphic rock art painted in more than two colors in the region. The polychromic rock art of Upper Tibet is religious in nature, depicting holy monuments, symbols, and ritual implements.

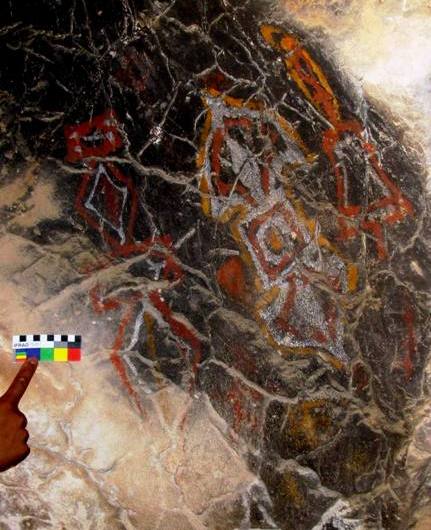

Both darker and lighter shades of red ochre, as well as white and yellow pigments, were used to produce this pictograph. It appears to date to the early historic period (650–1000 CE) and to portray a chorten (mchod-rten), a type of religious monument still popular in the Tibetan world today. If this polychrome painting was of the protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE), it would be better identified as a sekhar (gsas-khar), tenkhar (rten-khar), or some other kind of pre-Buddhist monument. I must emphasize that the age of rock art will only be established with certainty when scientific analysis becomes more feasible. The pointed tip of the shrine and the animal-like red ochre motifs in close proximity suggest a non-Buddhist religious orientation. The fluidly drawn ochre motifs appear to have been laid down in the same timeframe as the shrine, as they exhibit the same wear characteristics and light colored pigment. These pictographs were published as a b&w line drawing in my book Divine Dyads (1997: 262), and as a photograph in Zhang Zhung (2008: 160). See ‘Books’ on this website for bibliographic information.

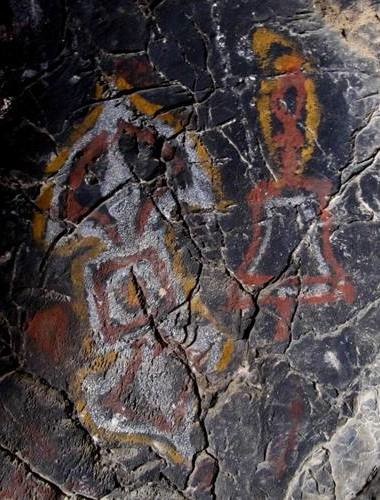

Fig. 2. Another polychrome depiction of a shrine (lower figure) and a bichrome anthropomorphic subject (upper figure) found at the same site as fig. 1.

The upper portion of the shrine has worn away under a haze of diffused white pigment. This pictograph was at least 20 cm in height. The five or six multicolored graduated tiers securely identify it as an image of an early religious monument. The human-like figure (nearly 30 cm in length) was painted using white and red ochre pigments. The three lower extensions give it an ithyphallic or three-legged appearance. With what appear to be outstretched arms and an almost horizontal stance, this figure seems to portray the extraordinary. These two pictographs can be assigned to either the protohistoric period or early historic period. At this same rock art site there is also a red and white geometric motif.

Fig. 3. This symmetrical figure was painted in close proximity to the shrine in fig. 1. It adds black (manganese oxide?) to the repertoire of pigments known in the region. This highly worn figure may be anthropomorphic in character. It has a talismanic or iconic aura about it. Protohistoric period?

Fig. 4. This polychrome chorten is of a general design painted and carved throughout Upper Tibet. Note the long red-colored banners extending from the spire.

The chorten (aprox. 35 cm in height) is found in a small cave with three mouths and minor structural remains, in the central Changthang. At one time this cave must have been used for religious functions. The counterclockwise swastika drawn in the same red ochre and exhibiting similar erosional traits lend a non-Buddhist identity to the shrine. We might therefore refer to the painter(s) as belonging to a bon cult. There are four other red and yellow ochre counterclockwise swastikas in this cave. The finial of the chorten resembles the ‘bird horn, bird sword’ (bya-ru bya-gri) used by Bonpo over the last millennium to crown religious monuments. The short football-shaped spire is divided into three segments. The lowermost tier of the pictograph was painted in yellow, orange and red ochre. With the white pigment of the other tiers, this makes a total of four distinctive colors. The shrine and companion swastika are likely to date to the early historic period.

Fig. 5. This polychrome panel at the base of a cliff was created by a practitioner(s) of localized bon cults, which existed in the eastern Changthang until circa 1200 CE.

These cults were tantamount to or otherwise related to the Bon religion that arose in the late 10th century CE. The pictographs are assignable to the 900 to 1200 CE time period. Four different colored pigments were used: white, yellow, red, and blue-grey. The panel is comprised of three counterclockwise swastikas, flaming jewels motif (nor-bu me-’bar) and the Tibetan letter A painted on a yellow and blue-grey ground. This rock art suggests that residential ruins in close proximity also belonged to bon adherents. If they had been built by Buddhists, they would have carved or painted some sign of their presence on the nearby cliff.

This is an early version of the motif made in a style also represented in copper alloy talismans called thokchas (thog-lcags). The three jewels and five tongues of fire are in red and white while the ground is blue-grey. A considerable amount of time and effort went into making this and other pictographs of the panel. Given that inhabitants in this area were familiar with at least four different mineral pigments, we might expect that the walls of their residences were also colored in a similar manner, the painting of external walls of buildings in these colors being a well established tradition in Tibet.

Fig. 7. From left to right: a Buddhist ritual dagger (phur-pa), thunderbolt (rdo-rje) and bell (dril-bu) painted inside a cave. The color calibration card in the photograph is 10 cm in length.

I have not found art historical evidence to indicate that the type of bell depicted here was manufactured in Tibet before 1000 CE. On this basis, the rock art can be attributed to the vestigial period (1000–1300 CE), if not to an even later period. The lack of heavy wear and discoloration is physical evidence supporting such a late date. A yellow (orpiment?), a red, and a white pigment were used to adeptly render these essential Buddhist ritual tools. The pigments have a finer consistency, smoother texture and different color quality than those typically used in Upper Tibetan rock art. This seems to suggest that the artist used pigments designed for the painting of scrolls (thang-ka).

The cave (22 m x 5 m) in which the pictographs occur overlooks a broad plain beyond which is the holy mountain Mayo Kawa (Ma-g.yo ka-ba). On the more than 3 m high ceiling of the cave there are two red ochre counterclockwise swastikas, said in local folklore to have been made by the lhadre (lha-’dre) spirits. There are also three or four red ochre counterclockwise swastikas on the right wall, and a large and a small one on the rear wall, as well as a swastika oriented in the same direction on the left wall of the cave. The juxtaposition of non-Buddhist and Buddhist motifs in the same cave may indicate historical interplay between these groups. Buddhist and bon rivalries are reflected in rock art erasures and palimpsests at various sites in Upper Tibet (see November 2012 Flight of the Khyung), and conflict may possibly also be signaled in the rock art of this cave. Any such contention might explain why so much effort was expended to fashion Buddhist ritual symbols in the cave. They could have functioned as symbolic means for bringing the site into the Buddhist remit. A photograph of the bell and thunderbolt was first published in Zhang Zhung (p. 163). In this photograph a yellow clockwise swastika connected to the same group of pictographs is also visible.

Fig. 8. A close-up of the bell and thunderbolt, symbols of wisdom and compassion in Buddhist practice. The drafting skill of the artist(s) is self-evident.

Fig. 9. A close-up of the red and white dagger. This implement is used in the exorcism of demons and in other types of wrathful ritual practices.

Fig. 10. A bichrome wild yak (’brong), which has been hit by the arrow of a standing archer (legs of hunter visible on top left side of image).

The inner body (representing the life-force?) of the wild yak is outlined in red ochre while the outer body and belly fringe was drawn in brownish yellow ochre. This pictograph belongs to a very early and important phase of rock art in Upper Tibet. This rock art, characterized by angular lines, minimal elaboration, and a bold execution, may date to the Iron Age (700–100 BCE), but a slightly earlier or somewhat later date cannot be entirely ruled out.

Fig. 11. Another wild yak from the same cave as the specimen in figure 10. This wild yak also has a red ochre inner body (incomplete) and a brownish yellow ochre outer body. This pictograph was made in the same timeframe as fig. 10.

Fig. 12. A unique motif consisting of a face-like core ringed by two circles and circumjacent petals (aprox. 70 cm in diameter).

This pictograph is situated 3 m above ground level over the right side of the entrance to a large cave. I learned about this striking painting some years ago from a Tibetan friend who lives in the area, but it was only in 2012 that I could locate it. Painted in red ochre and a white pigment, the identity of this painting is unclear. Although a flower and mandala immediately come to mind, elements of which may be incorporated into it, this pictograph seems to be neither. The periodization of this isolated rock art subject is uncertain, but a date subsequent to the early historic period does not seem indicated.

The Neolithic in Upper Tibet: Prospects for further research and exploration

Introduction

May’s newsletter touched upon the New Stone Age on the Tibetan Plateau, but with scant mention of Upper Tibetan sites from that period. In fact, little is known about the Neolithic antecedents of archaeological sites surveyed thus far in Upper Tibet. Calibrated radiocarbon values and informed archaeological data indicate that most of the documented monumental sites date to the Iron Age (700–100 BCE), protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE), and early historic period (650–1000 CE). Based on cross-cultural comparisons, certain rock art may be older and date to the Late Bronze Age (1500–700 BCE). Nevertheless, the prospect of some rock art belonging to the Neolithic cannot be categorically dismissed.

Neolithic cultural antecedents of surveyed monumental sites postdating circa 700 BCE in Upper Tibet are likely to involve the first and possibly the second of the following scenarios:

- They were exploited by Neolithic hunting and foraging peoples who left behind no permanent dwellings or other fixed structures.

- They were used by Neolithic settlers who may have practiced agriculture in some areas, leaving behind still not well catalogued rudimentary structures such as cairns, terracing, burials, and erected stones.

As to the cultural and ethnical relationship between these nebulous Neolithic inhabitants of Upper Tibet and the builders of the Iron Age residential and ceremonial monuments, potentially, both native and foreign origins can be proposed. Firstly, the Bronze Age/Iron Age culture of Upper Tibet may have primarily developed endogenously from an in situ Neolithic agrarian and/or pastoral society. This view is supported by genomic research indicating that there was no fundamental demographic break in the Tibetan genome between the Neolithic and subsequent periods (for more details, see May Flight of the Khyung). If archaeological research confirms this scenario, it must be predicated on native hunters, foragers and/or agriculturalists borrowing bronze and iron technologies from an extraneous cultural source(s), followed by indigenous development. This would have coincided with innovations leading to more socially and economically complex societies. Yet, it is also possible that a foreign group through invasion, migration or other forms of large-scale intrusion acted as the impetus for the establishment of Iron Age civilization in Upper Tibet. Any such interactions may have involved the introduction of new haplotypes into the Upper Tibetan gene pool. The welter of clans and tribes, some of foreign origins, said in Tibetan literature to have settled in Upper Tibet does suggest a process of demic augmentation in the region. The timescale of this human enrichment however is unclear in the literature. Only further scientific inquiry can flesh out these propositions, delivering us from the realm of inference and speculation to that of demonstrable facts.

The carvings of Horse Mountain Cave

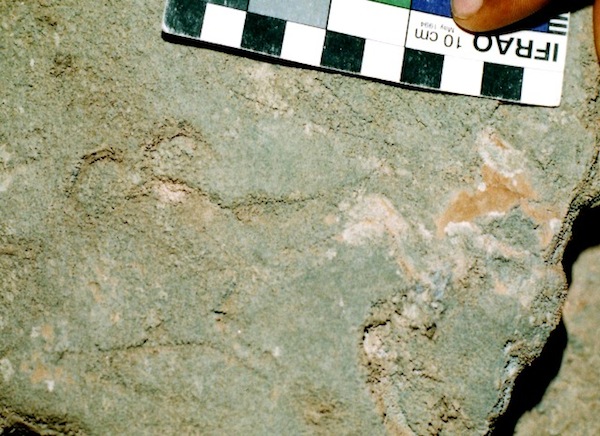

A unique rock art site called Horse Mountain Cave (Tari Drakphuk, Rta-ri brag-phug) is located in a remote corner of the northern Changthang. Together with Dondup Lhagyal of the Tibetan Academy of Social Sciences, I documented this site on the Autumn phase of the High Tibet Circle Expedition, in 2002. The petroglyphs in this cave were cut into a soft gray to red colored deposition that unevenly covers the limestone walls. The incised lines of these petroglyphs are very fine, which led me to believe that they were probably carved using a metal implement. Now I am not so sure and consider the possibility that a sharp non-metallic tool may instead have been used to create them.

The antiquity of the Horse Mountain Cave petroglyphs is open to question. The limited repertoire of animals and the style of the art indicates that they were made before the dawn of the historic era (pre-650 CE). A Neolithic date for their creation cannot be discarded, but any assignment to deep antiquity is highly conjectural. Nevertheless, given the unique carving medium, primitive style (simple but forceful), and extreme wear, these rock carvings may possibly be among the oldest in Upper Tibet. I present them here for inspection by readers who may have insights that have so far escaped me.

Fig. 14. Petroglyphs of Horse Mountain Cave. In the lower right half of the photograph is a deer-like carving. Harder to recognize zoomorphic petroglyphs cover the surface seen in the image.

Horse Mountain Cave (21 m x 15 m) with its high ceiling faces east in a limestone outcrop. There is also a long rear passage leading outside from the cave. The lack of substantial manmade structures and soot deposits on the ceiling suggest that the cave was not the site of intensive human habitation. This is also supported by the high elevation of the site (5100 m), its exposure, and the lack of a perennial water supply for several kilometers around. Rather, this cave may have been used as a shelter for roving bands of hunters from where they could easily surveil their environs.

On the left wall of Horse Mountain Cave, near the rear of the chamber, is a panel measuring less than 1 m². This panel extends to the cave floor. It boasts around 30 animals carved in outline that form a compact mass of figures. The petroglyphs have worn down significantly and have assumed the color of the surface of the soft veneer in which they were incised. The carvings are extremely delicate as the deposition hosting them seems to be steadily deteriorating. Most of the animal carvings are so disintegrated that determining their genera or species is not possible. The best preserved petroglyphs are near the top of the panel. Near the bottom of the panel are two separate figures that might possibly depict horsemen but this is far from certain. Of course the presence of equestrians would illustrate that the carvings did not date before the early Iron Age. Variations in execution suggest that different hands went into making the carvings. However, no physical clues indicative of older and more recent compositions are readily discernable. There appears to be a smaller panel of carvings that is even more degraded, located about 2 m closer to the mouth of the cave. This panel seems to have had around 12 animal figures. There is also a red ochre clockwise swastika in the cave, evidence for a later visitation.

Fig. 15. A wild yak. The vertical barbed lines represent the hairy belly fringe of a bull yak. A smaller animal carving is recognizable immediately to the left of these barbed lines. A drawing of the yak petroglyph was published in my book Zhang Zhung (p. 167). So far, other than this newsletter, this is the only reference to Horse Mountain Cave in my writings.

Fig. 17. A carving resembling a gazelle or antelope, Horse Mountain Cave. Unfortunately, this photograph is out of focus.

Fig. 18. Another blue sheep-like figure, Horse Mountain Cave. This photograph is also out of focus for which I apologize.

Neolithic sites, tools, and agriculture

I have discovered caches of core-and-blade stone tools in northwestern Tibet, which I leave in situ. The age of implements of these types has not been determined with any assurance. Radiometric sampling of materials from excavations carried out by Chinese archaeologists on the eastern fringe of Upper Tibet indicate that microliths found in the same stratigraphic context were produced as late as 1000 BCE (Zhang Zhung: 115). Microliths in close proximity to rock art sites in northwestern Tibet may also be of a relatively late date. These tools could have been used to fashion some of the petroglyphs at these sites, but careful study of tool edge wear and the carvings themselves is required to test this hypothesis. Nevertheless, on typological and technological grounds, certain microliths discovered in Upper Tibet are substantially older than 1000 BCE.

Known Neolithic sites in Tibet are concentrated on the central and eastern portions of the Tibetan plateau. These sites also exist in Upper Tibet but in what numbers is still unknown. In has been two decades since the discovery of a Neolithic site in Ruthok was first announced by Chinese archaeologists. Said to date to 3000 or 4000 years ago, finely polished stone implements and fragments of painted ceramics were found there (Li 1995; Hu Xue Tru 1993). However, no scientific excavations of potential Neolithic sites have been conducted in Upper Tibet, thus the extent and nature of this period in the region remains extremely sketchy.

It is not known whether agriculture in Upper Tibet has a Neolithic origin or belongs to a later period. My personal view is that the cultivation of barley in lower elevation parts of Upper Tibet probably began in the Neolithic when the climate was more amenable to growing food crops than in any major period since then. Agriculture can be traced to the Neolithic in the central and eastern areas of the Tibetan plateau, and I find no cogent reason why this should not likewise be the case in Upper Tibet and Ladakh. These speculations are all well and good but scientific evidence is needed to confirm or reject them.

The origins of animal domestication and stock rearing in Upper Tibet is also an unknown quantity. The opinions of archaeologists vary wildly in this regard and range anywhere between 8000 BCE and 1000 BCE. I am inclined to see a later date as more plausible, for Upper Tibet was a plentiful source of big game animals, which may have acted to retard the technological and economic transformation to a pastoral and agrarian way of life. Other researchers have their own valid reasons for the positions they take on when animal domestication began in Tibet. The hard archaeozoological evidence is still lacking though. As it now stands, archaeobotanical data from Tibet is also woefully inadequate. More fieldwork and analysis is demanded to fill this void with the requisite morphological, isotopic and molecular evidence.

The Stone Age in Ladakh

May’s newsletter analyzed evidence of Neolithic cultural and demographic forces from East Asia buffeting the Tibetan plateau. To round out this discussion a little bit better, let us turn to Ladakh. The Indian archaeologist S. B. Ota (1993) reports that in 1985, his peers, C. Tripati and associates, discovered scrapers, cores, and choppers (both unifacial and bifacial) in a stratified context from terraces along the Indus river, near the Ladakhi villages of Nurla, Khalsi, Pashkyum, and in the Kargil area. Using typological and technological criteria, these stones implements were dated in three phases to the Lower and Middle Paleolithic. The first phase is reported to resemble the Early Soan culture of the Siwaliks. Ota writes that these finds were also dated by Tripati et al. through the stratigraphic correlation of glacial deposits. Comparable choppers and scrapers have been discovered on the Changthang by Chinese archaeologists and dated to the Upper Paleolithic (for more information, see Frenzel). This discrepancy measured in the tens of thousands of years reveals that the actual age of these lithic finds remains to be conclusively determined. Other assessments suggest that such assemblages of stone tools may be much later than originally thought, and of Epipaleolithic or even Neolithic origins. Ota also discovered choppers and axes of the same type on a terrace near the bank of the Indus opposite the village of Alchi (A-lci). Wisely, he notes that any assignment of these artifacts to the Lower Paleolithic is premature.

Ota (ibid.) also reports that K. K. Sharma et al. discovered a fire pit near the Ladakhi village of Gaik, in the late 1980s. A piece of charcoal from this fire pit was radiocarbon dated to the Neolithic, circa 6700 BCE. This date arrived at for human activity reflected in the existence of a single hearth at Gaik must be viewed with a good deal of caution. It is not clear how the sample was collected nor what precisely was its stratigraphic context. Moreover, the calibration of the radiocarbon age may have been compromised by out-of-date chronometric protocols.

Three samples of charcoal extracted from hearths excavated from a terrace along the Indus near Kiari, 10 kms from Gaik, have yielded calibrated radiocarbon dates of circa 900 BCE (Ota, ibid.). A saddle quern, pestle, burnt clay ball, and burnisher were recovered from among these fire pits. A few pot-shards were also found. This handmade pottery is described as redware with a light brown slip and a medium thickness fabric. According to Ota, these ceramics most closely resemble those found at Burzahom in Kashmir. Among the faunal remains collected at Gaik by Ota was a significant quantity of domestic cattle, sheep and goat bones, many of which were charred and with cut marks. This led Ota to consider that the inhabitants of Kiari had a pastoral economy but one supplemented by some hunting and gathering. Reportedly, a quantity of goral bones were also unearthed at Kiari. Ota maintains that the bones of the domestic animals at Kiari are larger and somewhat differently formed than those of the Indian plains. If Ota’s preliminary osteological observations hold true, it is a very important strand of evidence, demonstrating that pastoralism in Ladakh had assumed a specific highland form of biological adaptation by circa 900 BCE. Ota is also of the opinion that the hearths were used on a temporary basis at seasonal camps. He detected no evidence of permanent structures at Kiari.

The most fundamental question concerning the Kiari finds is: what stage of technological development is represented here? Was this a Neolithic site or a late Bronze Age site where metal tools and objects merely eluded detection or happened to be absent? The affinities of the Kiari ceramics with those of Burzahom suggests a Neolithic identity but confirmation through the discovery of more intact ceramics in Ladakh would be useful. While I have suggested that the Neolithic in Upper Tibet may have persisted until circa 1000 BCE because of a generous supply of wild herbivores to hunt, this is harder to hypothesize for the bank of the Indus river in Lower Ladakh. This is a region not likely to have been as well endowed with large game animals as the high plateau. Moreover, this is a territory with much arable land, water for irrigation and wood for construction. Perhaps therefore two cultures or social groups occupied the same region: hunters and pastoralists in the Indus valley bottom and farmers among the alluvial fans. I am persuaded to believe that circa 900 BCE, the sites along the Indus river terraces were used for specialized economic activities at the same time farming was being carried out in suitable locales. The fundamental complementarity that exists between pastoral and agricultural activities in many regions may bear this out. Thus the fire pits found at Kiari and Gaik did not necessarily belong to people that were exclusively nomadic or semi-nomadic. More questions I am afraid for which there are still no answers.

Unfortunately, not much progress has been made since the 1980s in understanding the Neolithic in Ladakh. Ota, in a recent paper (2012), poses his own grand question: “…whether the ‘Neolithic package’ came to China through the Hexi Corridor (Flad et al., 2007) or along the Upper Indus and Yarlung Zhangbo (Miehe et al., 2009).” This question seems to overreach the mark a bit, as the bulk of the Tibetan plateau lies between Ladakh and China. What of the so-called Neolithic package (sedentary settlement, cultivation of food crops, animal husbandry, followed by ceramics production) in Tibet? Moreover, as the May newsletter conveys, the transfer of technological and economic strategies from one biogeographical region to another is not effected without some modification. These material and subsistence strategies have to be tailored to the environmental and cultural exigencies of the region to which they have been transported. Finally, the potential for independent innovation must be taken into consideration.

The borrowing of elements of the Neolithic package over a wide swathe of Central and East Asia, therefore, is more likely a matter of picking and choosing what was appropriate rather than strict adherence to the economic and technological regimes of other peoples.

Like their Chinese counterparts, Indian archaeologists have been rather lax, squandering much time and many opportunities to advance the study of the Neolithic on the Tibetan plateau. On an optimistic note, this discovery is still a wide open race. Any runners out there?

Bibliography

Flad, R. K., Yuan, J., Li, S.C., 2007. “Zooarchaeological evidence for animal domestication in northwest China” in Developments in Quaternary Sciences, vol. 9, pp. 167–204.

Frenzel, B., Huang Weiwen and Liu Shijian. “Stone artefacts from south-central Tibet, China”

http://www.quartaer.eu/pdfs/2001/2001_02_frenzel.pdf

Hu Xu Tru. 1993. Xizang Kao Ku Da Gao. Lhasa: Xizang Jenmae Tru Ban Zhu.

Li Yongxian. 1995. “New Discoveries in Tibet” in China’s Tibet, no. 6. pp. 22–23. Lhasa.

Miehe, G., Miehe, S., Kaiser, K., Reudenbach, C., Behrendes, L., Duo, L., Schlütz, F. 2009. “How old is pastoralism in Tibet? An ecological approach to the making of a Tibetan landscape” in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, vol. 276, pp. 130–147.

Ota, S. B. 2012. “Mountain environment and the early human adaptation in NW Himalaya, India: A case study of Siwalik Hill Range and Leh valley” in Quaternary International, vol. 29, pp. 31–37.

_____1993. “Evidences of Transhumance from Ladakh Himalayas, Jammu and Kashmir” in Current Advances in Indian Archaeology, vol. 1 (eds. R. K. Ganjoo and S. B. Ota), pp. 91–110. Nagpur: Dattsons.

Next month: A unique collection of rock art tabernacles and the old turquoise of Tibet!