January 2014

John Vincent Bellezza

Happy New Year! May 2014 bring you peace and happiness, whatever your political, religious, or cultural affiliations might be. This month we complete our study of Thakhampa Ri, one of Tibet’s most important rock-art sites. As you shall see there are more extraordinary images to enjoy in this issue of the newsletter. The final feature concerns evidence for the existence of tigers in ancient western Tibet. Intriguing material, if I may say so.

Hunters, Warriors, Shamans, and Lovers: Chronicles of ancient life at Thakhampa Ri—Part II

In addition to the main panel of Thakhampa Ri examined last month, there are nine smaller rock panels at the site and a few desultory petroglyphs here and there. The most important of these other panels is the lower one of the central outcrop (for location, see Fig. 2 in December 2013 newsletter). A wealth of petroglyphs are found on it including kinds of compositions not represented on the main panel. There are nevertheless may parallels in form and function between these two panels, the handiwork of a people who shared the same cultural idiom.

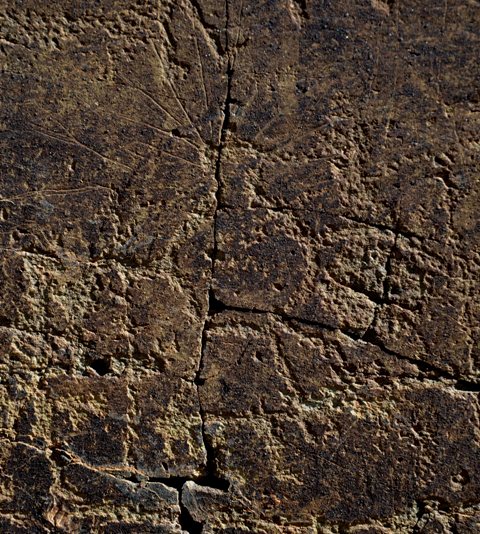

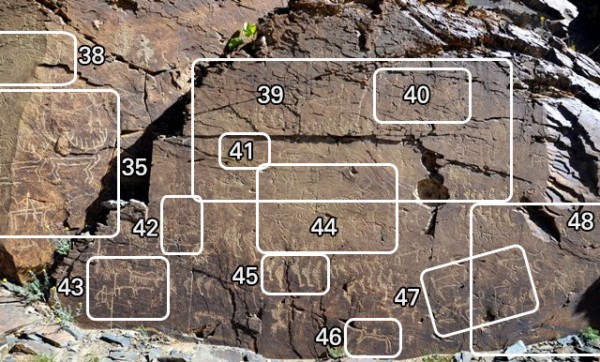

Fig. 34. The lower panel of rock at Thakhampa Ri (approximately 3 m x 1.5 m). This panel is naturally divided into west and east halves by the strike of the rock stratum. The locations of rock art selected for individual depiction are designated.

Like the main panel, the lower panel of the central outcrop is crisscrossed with horizontal lines of ‘backpackers’. There are at least seven of these lines of varying length. There is much individuality expressed in the forms of these figures, as if each one depicts a different personality. Perhaps shown walking across the very landscape of Thakhampa Ri, a panoply of activities takes place around them. While many hands were probably involved in the creation of this chronicle of ancient life, the petroglyphs exhibit a similar range of carving techniques, styles of execution, and physical wear characteristics, indicating that they were created in the same timeframe. As explained in last month’s newsletter, these petroglyphs can be provisionally dated to the protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE).

Fig. 35. The west side of the lower panel depicting a variety of related anthropomorphic and zoomorphic compositions.

At the bottom of the image a mounted archer (with recurve bow) wields a circular object in the other hand. It is as if the archer is about to lasso the yak behind him, but this would only be possible if this animal was of the domestic variety. However, as the archer is depicted about to shoot an arrow, it is unlikely that he is dealing with livestock. Therefore, although the yak and horse rider appear to form an integral composition, they may possibly have been created to portray separate ideas and activities. Above the yak and archer is a line of four stags, each with a large set of antlers. These deer have bodies rendered in the same style comprised of long, straight, angular lines. The two stags on the right turn their heads back to look upon the other two. A religious shrine known as a chorten was carved over parts of three stags.

The chorten has a square base that rests on a two-tiered plinth (50 cm in height). There are four stages above the base and a round and square midsection. The spire of the chorten is squat and is surmounted by a triangular finial. This chorten can be assigned to the early historic period (650–1000 CE). Its identity (Bon or Buddhist) cannot be determined. To the left of the chorten is a geometric design consisting of a square with an X in it. Above the design two figures appear to be fighting (see Fig. 37). On the right side of the chorten two anthropomorphs (humanoids) face each other with long objects, They appear to be locked in battle or a martial contest using long pikes or poles. The same type of composition is located underneath the square midsection and spire of the chorten. The figure on the right of this struggle scene is still visible while his opponent has been mostly obscured by the chorten. There are two other such compositions on the lower panel (see Figs. 39, 40). The chorten may possibly have been carved to ritually or symbolically suppress or neutralize these patently aggressive scenes, an act of piety from the Lamaist era.

The carved lines of the chorten are considerably wider and more roughly textured than those used to make the deer. The chorten also exhibits considerably less re-patination (not very noticeable in this shaded image), suggesting that it was made in a significantly later period. This is the only true palimpsest at Thakhampa Ri. The stags may possess naturalistic, ritualistic, mythic, or narrative significance.

Fig. 37. A close-up of the two opposing anthromporphs in Fig. 35 (height of each figure around 10 cm).

These appear to be men sparring or involved in some other martial display. In any case, the position of the bodies and arms resembles a classic depiction of pugilism. The two broad-shouldered figures don long, pointed hats or helmets, and they appear to be attired in one piece outfits. Their legs are unclad below the knees. As noted in last month’s article, the temporal status of such compositions cannot be determined. They may have been intended as portraits of contemporaneous life or as mythic or historical depictions. Also, discerning human figures from legendary or supernatural ones is beyond our capacity.

Fig. 38. An exciting composition situated directly above those examined supra. It shows an encounter between an anthropomorph and zoomorph (total length 27 cm).

The anthropomorphic figure, legs bent, holds a round object (drum?) in one hand and possibly a club-like object in its other hand. The much larger zoomorphic figure has the gaping mouth and curling tail characteristic of carnivore rock art in Upper Tibet. This animal appears to be rearing up at the anthropomorph. The four vertical lines in its body seem to simulate the stripes of a tiger (the looped tail is also felid-like). There are a number of striped carnivores in the rock art of Upper Tibet that can probably be identified as tigers (see August 2012 Flight of the Khyung and article below). The identity of the horizontal line beginning at the mouth and extending back to the rear of the body is unclear. Perhaps it represents the animal’s life-force or source of magical power. The tail of the creature appears to be comprised of three volutes, a motif seen in the horns of stags and as body ornamentation in Ruthok rock art. This kind of art is connected to the Eurasian ‘animal style’.* The signification of this composition cannot be known with any assuredness, for the creator and his or her cultural milieu have long since passed away. As a point of discussion, I shall conjecture that it depicts a priest or spirit-medium trying to appease or exploit a tiger spirit, in either a contemporaneous or historical context. To this day, Upper Tibetan spirit-mediums rely on remedial spirits in the form of tigers for curative and apotropaic purposes.**

For more information, see Bruneau and Bellezza: 2013. “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’ in Revue d’etudes tibétaines vol. 28, pp. 5–162. See Bellezza: 2005. Calling Down the Gods: Spirit-Mediums, Sacred Mountains and Related Bon Textual Traditions in Upper Tibet, Tibetan Studies Library, vol. 8, Leiden: Brill.At the top of the panel two pairs of fighting or contesting figures with long objects are depicted. Below them is a line of around 18 backpackers. There is another line of backpackers at the bottom right hand corner of the photograph. Above this lower line of walkers there is just one figure of the type depicted in the dueling pairs. On the left side of the panel is a sun (see Fig. 41). To the right of the sun is a yak and an ungulate below it, and below that another yak (only partly visible in the image, for full view see Fig. 44).

Fig. 40. A close-up of one of the pairs of dueling figures on top of the panel (total length 40 cm).

The two heavy set figures seem to have sashes and largely uncovered legs. This depiction resembles a jousting tournament except that the combatants are not on horseback. It is possible, however, that some entirely other (ritualized?) activity is being portrayed in this scene. We simply have no way of being certain, at least with the body of archaeological evidence now available.

The sun is liable to have both literal and symbolic connotations in Upper Tibetan rock art. Sometimes it rises above animals and hunters as if the real heavenly body is being depicted. In other instances it is carved or painted in conjunction with a crescent moon and swastika, which is more reminiscent of a sign with abstract meaning. As in most cultures, the sun has life-giving connotations in Tibet.

This figure appears to wear a robe with a sash tied around the waist. This garment comes down to about knee level. Fine lines that resemble rays radiate from the head. These lines appear to have been added later, because they were cut with a sharp-edged implement, while the main composition was more roughly etched into the rock. They also have different patination qualities. I dare not speculate on what this anthropomorph might represent. Abraded areas flanking the figure have not been identified (the one on the left resembles an anthropomorph). They may also possibly be objects held or arrayed around it.

The anthropomorphic figure appears to be running and carrying a long stick-like object in its right hand. Closest to this figure are two stick animals made using the same technique of etching and exhibiting similar wear qualities. The yak above them appears to belong to the same composition as well. This yak, with its long belly fringe of barbed lines, elongated rectilinear body, and big humped withers, is typical of Upper Tibetan rock art. The tail and bottom half of this yak have been lightly retouched. The manner in which its tail is raised straight up signals alarm or anger. This may be a hunting scene, the two stick animals the hounds of the hunter (these animals have the pointed ears and tails of carnivores). Above the yak, there is a crudely carved ungulate (not visible in the image), but it may not be part of the same composition. The various petroglyphs on this part of the panel were made in a similar manner and display similar wear and re-patination.

Across the bottom of the image there is a line of nine backpackers, most of which have walking sticks. These sticks are inclined at various angles mimicking different stages of the gait of hikers. Their necks and heads are somewhat bent over as if carrying heavy loads. There are several other figures in this line, but they are not shown in the photograph. There is another long line of backpackers below them (see Fig. 45). To the right of the visible line of walkers, a sun with at least 16 rays was carved (not shown). Above the walkers, two wild yaks appear to be running (each around 23 cm in length). They have wedge shaped tails and big rounded horns, common features in Upper Tibetan rock art depictions of wild yaks. The yak on the right has scroll-like body ornamentation (also partly visible in Fig. 39). Above the yak on the left is an anthropomorph that may be brandishing a bow with its left hand. This simply executed figure has a pointed head, square body, and stick legs. To the right is an ungulate that resembles a wild sheep (also seen in Fig. 39). In between them is a petroglyph of indeterminate identity. Perhaps these three figures are part of an integral composition, but it is hard to know, because many carvings in the proximity share similar stylistic and physical traits. This suggests more widely that the creation of the petroglyphs was part of the same ambitious project to embellish the lower panel (and perhaps others) at Thakhampa Ri.

There are five more walkers to the right and five to the left of those shown in this photograph. This row of backpackers was more crudely executed than that in Fig. 44. These two lines of figures were almost certainly made by different artists.

This quadraped has something on its back but it is not clear if it is a rider or some kind of object. There are a few other animal carvings in the proximity, but it has not been determined if this figure comprises a composition on its own or if it was depicted in concert with others. Note the slight retracing of the belly of the animal.

This yak and the herbivore above it were carved with strong, deft lines. At the bottom right is the beginning of a line of backpackers. For a full image of the wild yak in the upper right corner see Fig. 48.

Animals of Fig. 47 are seen on left side of this image. The uppermost yak among them is 24 cm in length. Above these animals, on the left side of the image, is an anthropomorph of the same form as the duelers we have examined, save that it is a lone figure. It is not clear if this figure is part of the animal scene below, possibly as a hunter, or if it was carved to stand alone. Be that as it may, animals depicted in isolation are very common in Upper Tibet. An arc of backpackers runs across the bottom of the photograph. This composition is unique at Thakhampa Ri, in that two lines of walkers come from opposite directions. They meet in the middle on what might have been envisaged as the top of a hill.

This hunting composition is located on the lower middle panel of the central outcrop of Thakhampa Ri. According to Sonam Wangdu (1994: 87), the dimensions of this panel are 80 cm x 30 cm. The two hunters are shown ready to shoot their bows at the wild yaks, which are moving away from them. The heads of the hunters seem to have a zoomorphic quality, or they wear tall headgear. The anthropomorph on the right may have a gaping mouth just like the carnivores of Upper Tibetan rock art. These hunters have triangular bodies not unlike some other figures at Thakhampa Ri. The figure on the left is clearly armed with a recurve bow, and his reproductive organ appears to be exposed.

Fig. 50. Two anthropomorphs actively engaged with one another, as portrayed by two long lines that connect them. Below this pair is a similarly styled figure holding a long object upright. The color calibration card in the image is 10 cm in length.

The nature of interaction between the pair of joined figures is not apparent. With their arms sharply bent at the elbow, they seem to be vigorously acting upon the two long objects they are holding or repulsing. These may be duelers fighting with long poles, but any number of other interpretations are also permissible. The two are attired in knee-length robes. The wedge-shaped heads and hourglass bodies of the figures is part of a style of art found at other rock art sites in Ruthok as well. This style is representative of the protohistoric period. This composition is found on a panel immediately west of the lower panel of the central outcrop, at the same elevation. According to Sonam Wangdu (1994: 82),* its dimensions are 90 cm x 90 cm.

See last month’s newsletter for bibliographic details.

Fig. 51. Close-up of the lower anthropomorph in Fig. 50. In addition to the long object in its right hand, the left arm is held akimbo. It is as if this figure is mediating in the encounter above.

In the center of the panel is a design consisting of a square with an X, as found on the lower panel of the central outcrop (see Fig. 35). This carving measures 8 cm x 10 cm; its identity unknown (symbolic or representational?). There are copper alloy talismans (thog-lcags) of significant age having this same form. Arching over the square with an X motif are five animals. The closest figure to the left of the design is unidentified: it could either be an anthropomorph or zoomorph. The animals (from left to right) are: wild yak, deer, wild sheep (?), indeterminate, and antelope (?). The stag and ostensible antelope are ornamented with double volutes, a hallmark of wild ungulate rock art in Ruthok. Below the animals, to the right of the square with an X motif, an equestrian leads a horse. This horse carries something on its back, but some retouching of the carving has obscured its identity. The body of the horse is also ornamented with modified volutes. The figure leading it has something in its right hand and something (a sword?) tucked into its sash. Below the square with an X, an animal and anthropomorph are faintly visible. The more advanced re-patination of the petroglyphs of this panel and the style of art suggests that they predate other carvings at the Thakhampa Ri site. This panel of figures may be attributable to the Iron Age (700–100 BCE).

The equestrian or groom is clearly leading the horse. This figure seems to wear something on its head. This composition may depict a ceremonial or ritual activity. The wild ungulate above them has also been subjected to subsequent manipulation. Both figures have undergone some retouching, visible as light-colored fine lines. The sinuous horns of the wild ungulate probably identify it as an antelope, a common species in Upper Tibet. The animal to the left of the ostensible antelope appears to have a tail held over the body and pointed ears. These features may possibly identify it as a carnivore. The caprid above it has also been lightly retouched.

The general form (widely branching antlers with prominent hooked points, and double-volute or scroll-body ornamentation) of this deer are stylistic features typical of Iron Age art. This genre of art constitutes the Upper Tibetan version of the Eurasian ‘animal style’, which is mostly of the Iron Age. The Tibetan variant generally has a more naive look and solid form. While volutes are common embellishments in the animal style, the scroll of the type depicted here is a trait of Upper Tibetan and Ladakh rock art.

The figure has a knee-length robe, outstretched arms, and spread legs (12 cm tall). It may be depicted as wearing a tall hat. Having the aspect of some kind of display or performance, this anthropomorph seems to grasp an object in its right hand. Like other petroglyphs on the panel, this quite heavily re-patinated figure appears to predate other carvings at Thakhampa Ri. Sonam Wangdu (1994: 92) states that this figure may be dancing (and mistakenly gives its height as 18 cm).

A football-shaped object (shield?) at shoulder height is interposed between the pair of figures (each is around 10 cm tall). They wear knee-length robes and have fairly well defined waists. Each one holds a linear object in one hand. Both figures also seem to have a linear object tied to their waists or tucked into their sashes. The figure on the right has a squarish head. This may possibly be a fighting scene.

Fig. 57. Three carnivores on the same panel as Fig. 56 (each up to 13 cm in length). These roving animals are either wolves or felines. No quarry is depicted with them.

Fig. 58. Two animals on another panel of Thakhampa Ri. This composition appears to depict a carnivore pouncing on a wild ungulate (wild sheep?). The carnivore is either a feline or wolf (33 cm in length). We can of course infer that the creators of this composition were keen hunters and observers of the natural world.

Fig. 59. Two pairs of anthropomorphs on another panel of Thakhampa Ri. According to Sonam Wangdu (1994: 88), the dimensions of this panel are 70 cm x 80 cm.

The figure on the left in the upper pair extends one arm to touch a lead-like object attached to the smaller anthropomorph. In the other hand the figure on the left holds a long pole-like object pointing in the direction of its counterpart. The larger figure appears to wear something on its head, and a male sex organ may be depicted. The smaller figure seems to hold its right arm akimbo, and its left arm is raised as if gesturing. Its legs also convey a sense of movement. The larger figure of the lower pair also appears to grasp a lead connected to its partner. The left arm of the larger anthropomorph is held akimbo. Between its legs is a male sex organ. The smaller figure has outstretched arms. Between its legs a dot was carved, which may represent the female sex organ. By their physical appearance, it is not clear that these four figures were carved at the same time. The coupling of figures may possibly have been a later addition. This might explain why the upper left figure seems to be armed.

According to Sonam Wangdu (1994: 88), these compositions portray two couples dancing. This might be the case; however, I know of no traditional dance still performed in Tibet where something is tied to the female. Perhaps, then, this is just a metaphorical link between the figures in each pair. That a male seems to be coupled with a female in each example supports the notion that they are dancing, but their portrayal may also be a more symbolic demonstration of conjugality. Furthermore, it is not at all evident if this is a depiction of a contemporaneous social reality or something from a historic or mythic setting.

Phallic depictions appear to be particularly numerous at Thakhampa Ri. Many of the activities depicted such as combat, martial contests, and hunting were probably largely the preserve of males, as they were in more recent times. However, the gender of the numerous backpackers (around 180 in total) is indistinguishable.

The horse rider armed with a recurve bow is preparing to shoot an arrow at the wild yak. One arrow has already struck the prey in the neck. This typical Upper Tibetan hunting scene seems to have been designed to demonstrate a positive outcome, possibly as an intention or aspiration before the actual event, or perhaps after the fact as a recording of the activity or as a means of thanksgiving. The prowess of hunters is plainly demonstrated in such compositions. A potent social dimension is surely present in this kind of composition with prestige, status, and skill probably involved.

Sonam Wangdu (1994: 87) reports that the dimensions of this panel are 90 cm x 70 cm. It is situated 2 m above the upper middle panel, which we studied in last month’s newsletter. At the very top of the panel is a solitary stag (30 cm long). This deer appears to be shown with a male sex organ. Below the stag two carnivores chase a wild ungulate (wild sheep or antelope). A third carnivore off on the right may be part of the same scene. As elsewhere in Upper Tibet, hunting by humans and animals is a very important artistic theme at Thakhampa Ri.

Fig. 62. Two raptors soaring head to head, a rock art composition found at another site in the vicinity of Thakhampa Ri.

These birds have wide tails and simple stick wings (total length 40 cm). This attractive composition is likely to be infused with considerable meaning and significance. Perhaps the birds depict a male-female dyad, which could have been construed as anything from simply naturalistic to redolent with cosmological, genealogical, or divine significance. An analogous carving is found at Thakhampa Ri (see Sonam Wangdu 1994: 93). In the Thakhampa Ri depiction the feathered and pointed wings of the two graceful birds touch. These two pairs of birds in symmetrical formation may date to the Iron Age.

This concludes our examination of Thakhampa Ri. There will be more site reports as well as thematic coverage of Upper Tibetan rock art in the months and years to come. I have documented a very large body of ancient art of various kinds Flight of the Khyung would like to share with you.

Tigers is ancient western Tibet: More evidence

Long live the tiger!

As regular readers will remember, in the August 2012 Flight of the Khyung, I present textual and rock art evidence suggesting that the Caspian subspecies (or an extinct Tibetan subspecies) once lived in the valleys systems of ancient western Tibet. There are numerous examples of petroglyphs of striped carnivores in this region. The most compelling rock art evidence shows striped carnivores hunting down wild ungulates. These kinds of prey-predator scenes seem to record facts of the natural history of Upper Tibet.

Here I furnish more such evidence that makes us stop and ponder the possibility that tigers once roamed in lands known as Zhang Zhung. First, though, I sound a note of caution: to confirm that the habitat of the tiger once extended into western Tibet requires paleozoological and genetic evidence. And we must wait first for experts in these areas of study to gather the requisite empirical proof from the field.

Fig. A. Two carnivores with anatomical features reminiscent of tigers attacking wild yaks, Late Bronze Age or Iron Age. Above these petroglyphs, a more clearly rendered striped carnivore also attacks a wild yak (see August 2012 newsletter for image). The mani mantra scrawled across the lower portion of the rock was engraved at a much later time (early historical period or possibly somewhat later). This mantra may have been carved to express compassion for the slaughter of animals.

Fig. B. A striped carnivore attacking a wild ungulate with curled horns, Late Bronze Age or Iron Age. This scene appears to depict a tiger and an argali sheep but it is too eroded and damaged to be certain. If this identification is correct, it suggests along with analogous scenes that any tigers in western Tibet hunted a variety of wild ungulates, as would be expected of this large species. Wild sheep are must vulnerable to predation by wolves (and tigers) in the winter when they come down into the valleys and basins to graze.

There is yet another piece of evidence that suggests tigers may have been native to western Tibet. This evidence is textual in nature. In the Old Tibetan funerary ritual text known as Sha ru shul ston rabs, there is an origins myth that describes an impending epic struggle as follows: “It would be an example of the grinding of the teeth [and horns] of the tiger and [wild] yak joined in combat” (So ’dar (C.T. = brdar) ba ’ǐ dpe ni / stag dang g.yag la blangs so //). While this account may be metaphorical in nature rather than an expression of an ancient ecological reality, companion origins myths in the text are localized in far western Tibet. The narratives they contain are explicitly set in the headwaters region of the Sutlej, Karnali, Brahmaputra, and Indus rivers (Chu-bo bzhi), as is the ‘tiger’ rock art shown above.

The cosmogonic myth noting the battle between the tiger and wild yak is extremely noteworthy, because it provides the oldest known Tibetan account of the origins of existence. The Sha ru shul ston rabs was probably written circa 900 CE (there are older origins myths among the Dunhuang manuscripts, but these pertain to specific ritual traditions). In this general myth of creation it is the sky and ocean who give rise to existence (srid-pa). For your reference, here is a paraphrased version of this action-packed origins story:

Once upon a time, the mighty rearing-up blue sky and the majestic shimmering-expanse ocean, these two, could not agree on who was greater. This was the time of their fight. It was midnight. At that time, these two pounded a stake into the ground [to demarcate the fighting ring]. They were to draw the bow of the sharp [arrow]. They donned impervious armor. They went to the site of their combat. They would fight in the manner of two wild yaks of the north who grind their horns against each other. The small rocks would be kicked about like hail falling from the sky. They would snort at each other like the roar of the dragon of the sky. The swooshing of their tails would be like the covering of darkness. It would be an example of the grinding of the teeth of the tiger [and horns] of the [wild] yak joined in combat. However, the fight between these two wild yaks did not take place. They pacified (disengaged) their locked, yes, horns. Their tails, yes, came down. Although agitated, the two separated. They each went their own way. Then the mighty blue sky and the magnificent ocean, these two, spoke. These two said to each other that a fight between them was inappropriate. They both agreed. They said, ‘You and I, both of us, shall found existence.’

For a more detailed and technical account of this etiologic myth, see Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet, pp. 210, 211. Bibliographic information at: http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/books/

Next Month: Thousand-year-old homes recently abandoned in Upper Tibet and more!