January 2012

John Vincent Bellezza

Happy New Year! We shall usher in 2012 with one of the most important symbols of the Tibetan cultural world, the khyung or horned eagle. As you shall see, there is solid archaeological evidence supporting Bon textual accounts of the antiquity of this noble figure. This issue, as part of a series of newsletters devoted to the findings of the Upper Tibet Rock Art Expedition II (2011), will also look at rock art conservation issues. It is essential that more people are made aware of the dangers facing the cultural heritage of Upper Tibet. So, let’s get started!

The horned eagle: Tibet’s greatest ancestral and religious symbol across the ages

All those familiar with Tibetan culture will know the khyung, the mythical horned eagle of Tibet. These fabulous birds come in many forms, painted and sculptural. Horned raptors are also found in the rock art of Upper Tibet, forming a subset of birds of prey with outstretched wings (depicted flying). Carnivorous birds (khyung, eagles, hawks, vultures, falcons, and owls) are important elements in many Tibetan religious traditions, myths and customs. The khyung has pride of place in Tibetan religious art soaring above the thrones of deities. According to certain ritual texts, its horns possess demon destroying properties. There are also textual indications that these so-called horns may actually be feathers such as those that form the crests of some avian species.

As with many other ancient motifs in Tibet, the khyung has a dual historical lineage: indigenous and Indian. Its Indian ancestry is the garuda line, flying creatures with the wings and tail of a raptor combined with anthropomorphic qualities. Native to India and Nepal, the garuda spread to Southeast Asia with the maritime expansion of peninsular kingdoms more than a millennium ago. It is now of course the national symbol of Thailand and Indonesia. With the spread of Buddhism northwards, the garuda was also introduced to Tibet (and from there to greater Mongolia at a later date). Reaching Tibet in the early historic period (650–1000 CE), the garuda became assimilated to the khyung, as Buddhism displaced earlier religious traditions of the Plateau.

So thorough was the iconographic and ideological merging of the garuda and khyung, the former became known by the latter name. The only major iconographic distinction remaining is that the khyung is depicted with horns while the garuda is not, but this rule is not hard and fast. While the Hindu garuda is the mount of the god Vishnu, the khyung is a vehicle for a good number of Buddhist and Bon protective deities. No mere workhorse, the khyung has come to symbolize a broad range of Buddhist concepts and doctrines as well. It was elevated to the status of a tantric tutelary god in both Buddhism and Bon. Associated with the fire element and space, the khyung is commonly propitiated to counteract diseases attributed to water spirits (klu). It is also the prime zoomorphic emblem of the profound philosophical and mystic tradition known as the Great Perfection (Rdzogs-chen).

The Bon religion has retained numerous accounts of the khyung set in the period before Buddhism swept over Tibet. Often these narratives have a Buddhist ring to them such as those describing the transformation of adepts into khyungs, a sign of their ultimate liberation. Moreover, tantric forms of the khyung in Bon (Me-ri and Ge-khod cycles) are replete with Buddhist-inspired imagery. Even the pentad of khyung that reside at Mount Tise (Kailash) in the Bon Mother Tantra (Ma-rgyud) are overlaid by a thick Buddhist philosophical mantle. However, this khyung of Buddhist persuasion is only one side of the story.

The Bon religion (and Tibetan Buddhism to a lesser degree) has also preserved a native form of the horned eagle. This khyung is a genealogical deity and uranic protective spirit. The most celebrated ancestral khyung is said to have appeared in Zhang Zhung as the divine progenitor of the Khyungpo tribe. Early human representatives of the Khyungpo are credited with founding the first temples (gsas-mkhar) of Zhang Zhung. It is generally believed by Bonpo that the Khyungpo migrated east into Kham (where its various branches are now very common), but when this might have taken place is not clear. The best known defender khyungs are in the form of divine mountains (lha-ri) and warrior spirits (dgra-lha). This type of khyung is thought to have been the ally of ancient adepts and kings. To this day, Tibetan spirit-mediums are said to have khyungs that watch over and aid them during trance ceremonies. The ubiquitous reach of the khyung as an ancestral totem and spirit comrade deeply influenced the material culture of ancient Tibet. The horns of the khyung are recorded as being the paramount symbol of sovereignty for the kings of Zhang Zhung. Ancient Bon priests are reputed to have worn robes and hats of khyung feathers and to have had magical instruments and armaments made from the body parts of these great birds. The khyung also lent its name to numerous toponyms in the Tibetan world. Perhaps the most famous of these is Khyunglung Ngulkhar, Zhang Zhung’s capital. So vital was the khyung that one Bon tradition claims it gave its old name (zhung [-zhag]) to Zhang Zhung. Finally, in this brief survey, mention must be made of the khyung’s archaic funerary function as a pyschopomp. This theme is explored in my forthcoming book, “Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet”.

The rock art record of Upper Tibet confirms that horned and crested raptors did indeed play a cultural role in prehistory. While the specifics of individual narratives cannot be verified, this archaeological evidence independently corroborates the historicity of the Bon textual tradition. The existence of horned raptors (probably eagles) in rock art right across Upper Tibet in antiquity encourages us to take the functions and significance assigned them in Bon literature seriously. Deconstructing the indigenous and Buddhist-inspired narrative edifice of Bon is a tall order. Nevertheless, the rock art shown below furnishes us with a strong point of reference.

I have already published some of the eleven horned raptors presented below in various books and articles, but never as a group. This selection of images constitutes many of those documented in the rock art of Upper Tibet (all of which will be carefully catalogued in the large online rock art inventory I am planning). Several horned raptors have also been recorded in Ladakh by Laurianne Bruneau and Martin Vernier. Dr Bruneau and I will be exploring these regional links in a forthcoming paper. Although it cannot be said with absolute certainty that horned raptors were called khyungs or zhungs in the prehistoric period, I shall use the former term for the selection of birds found in this newsletter. It is attested in Tibetan texts going back to circa the 8th century CE. More crucially, some early historic authors place their narratives in primal or prehistoric times.

With one possible exception, all khyungs portrayed below can be attributed to no later than the early historic period. They are provisionally dated according to style, technique of execution, wear characteristics, and the nature of other art at the same site and panel / boulder locations.

Fig. 1. Far western Tibet. This style of khyung was retained well into the historic period as part of the class of copper alloy talismans known as thokchas (thog-lcags).

Rather than in profile, the head of this khyung may face forward (the protuberances on each side of it representing ears?), just like most khyung thokchas. The horns of this particular rock art specimen have a double curve to them, as is also found in some prehistoric wild yak petroglyphs. Also, note the diamond motif on the breast and segmented wings. This khyung is part of a composition that includes anthropomorphic figures with ornithic traits. As I have speculated, it may possibly depict the celestial decent of the Khyungpo lineage (see http://asianart.com/articles/vestiges/index.html). I have also written that this rock art may date as late as the vestigial period (1000–1300 CE). However, further inquiry has shown that this is not the case. This style of rock art and its physical characteristics (wear, carving technique and repatination) can probably be attributed to the protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE). Chronometric analysis is required to verify this supposition but until that is possible; this will remain our working hypothesis.

Fig. 2. Western Changthang. This lovely khyung is found at a site with much early rock art. It appears to date to Iron Age (700–100 CE). As in figure 1, the two horns of the bird are clearly represented. Of special note is the treatment of the wings, which gracefully but powerfully fold inwards.

Fig. 3. Far western Tibet. The beak of this bird is blunted but its horns are very clearly depicted. Its long pointed wings and triangular tail recall khyung thokchas. This specimen dates either to the Iron Age or protohistoric period.

Fig. 4. Central Changthang. This khyung is very similar in style to fig. 3, except that its beak is more pointed. It hovers above a wild ungulate. Perhaps these two animals are emblematic of the dichotomous universe, a key cosmological concept in Tibetan archaic traditions. This horned raptor is best dated to the protohistoric period.

Fig. 5. Far western Tibet. Here we have a khyung with prominent tail and wing feathers. This motif consists of a row of parallel lines, which is reminiscent of the depiction of the belly hair on wild yaks in Upper Tibetan rock art. Iron Age or protohistoric period.

Fig. 6. Far western Tibet. This unusually large khyung (50 cm in length) sports a rather small set of horns. It was first documented on the UTRAE II. Like many other rock art specimens, it has a long thin neck. The tail and wings are thokcha-like in form. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 7. Western Changthang. This khyung is found at the same site as the example in figure 2 and likewise appears to date to the Iron Age. It is found amid many other animals carved on a large boulder. Like the horned bird itself, most of these figures are obscured by extreme wear.

Fig. 8. Far western Tibet. This large khyung was produced employing bold but shallow carved lines. Its beak points upwards as if the bird is shown ascending. In the middle of its round body is a swastika-like design. The prominent tail and wing feathers are congruent with those of raptors. Below the raptor a long-tailed carnivore is depicted. This carving appears to date to the protohistoric period.

Fig.9. Eastern Changthang. Khyungs painted in red ochre are only found in the eastern portion of Upper Tibet. This specimen with its long body and wedge-shaped tail has undergone much wear and the browning of the pigment. It dates to the protohistoric period or early historic period.

Fig. 10. Eastern Changthang. This red ochre khyung was depicted with a massive body and wings. Its horns however were drawn as thin lines. This pictograph, given the character of others found in close proximity, can be dated either to the early historic period or vestigial period (1000–1300 CE).

Fig. 11. Rather than horns, this raptor sports what appears to be a crest. It is located at the same site as the khyungs in figures 2 and 7 and can also be provisionally dated to the Iron Age. There is no body depicted below the diamond-shaped wings. What appears to be the ear is shown as a triangle opposite the rounded beak of the bird.

Contemporary threats to rock art in Upper Tibet

As recent incidents have shown, rock art in Upper Tibet is being destroyed at an unprecedented rate by road construction and vandalism. To date, no effective program of conservation has been instituted by the Tibet Autonomous Region government. Yet, this is the order of the day if Upper Tibet’s ancient rock art is to be saved from the greedy and ignorant.

Fig. 12. Pictured here is the site of Luring Nakha (Lu-ring sna-kha), Ruthok.

Luring Nakha was seriously damaged four or five years ago by workers widening a nearby road. The large light colored rock patch in the center of the rock formation is where the bulk of the site’s petroglyphs were located. It held a dense concentration of prehistoric rock art. There was no need to smash to smithereens this panel of stone for the road is situated a safe distance away. There is plenty of uncarved rock in the vicinity, so any need for this material could have been met easily without destroying precious rock art. Other panels of rock art at Luring Nakha were also decimated. Some rock art however has survived. The vanished rock art is documented in the 1994 publication, “Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings”. Hopefully, the powers that be will see to it that what is left of Luring Nakha is adequately protected, but thus far their track record is not very good.

Fig. 13. This is a picture of the recently erected monument at the famous and important rock art site of Rimodong (Ris-mo gdong), Ru-thok.

This marker in the above photograph was raised by the county government at the foot of the main portion of the site. The Ruthok county government deserves credit for trying to protect Rimodong, but much more needs to be done if it is to be spared the fate of other rock art. Excavations for the new road have come dangerously close to the monument, necessitating the restoration of the site if it is to be defended from erosion and misuse. While a second main panel of rock art at Rimodong is still largely intact, other carvings were obliterated during the widening of the road three years ago. Unfortunately, much of this rock art was never properly inventoried.

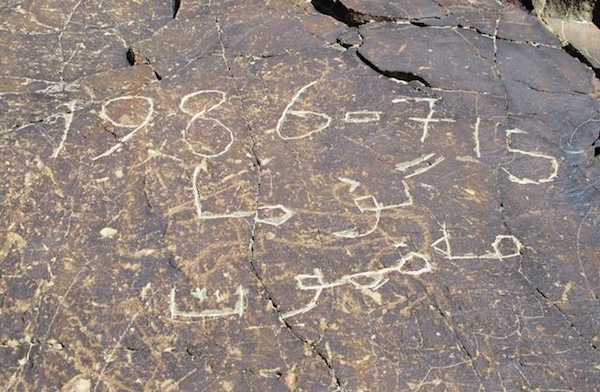

Fig. 14. Defaced rock art at Rimodong.

In the last five years, Rimodong has found its way into Chinese and foreign guidebooks and many more people are stopping along the roadside to visit it. Some of these visitors are poor sports and many petroglyphs have been defaced. In the above picture we see an early (1986) example of vandalism. This graffiti obscures ancient zoomorphic art.

It is essential that the rock art of Rimodong is given meaningful protection by the provincial and central governments, with clear recognition of its Tibetan cultural significance. For other sites it is too late. Not far from Rimodong there was a small but early rock art site called Driu Chuthang (Gri’u Chuthang), which I documented in 2000 (see “Antiquities of Upper Tibet”). It no longer exists; having been blown up by those assigned with the task of improving the main highway. With a little care, Driu Chuthang could have been saved; instead another piece of Tibet’s dwindling cultural heritage has been lost.