December 2014

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome aboard as Flight of the Khyung takes you to new heights in winter-solstice Tibet! This month the reader is treated to the special beauty of a rare assortment of Tibetan artifacts. The first article features an extraordinary golden burial mask that recently came to my attention, adding a new dimension to the study of Inner Asian funerary art.

The second article in this issue highlights several copper alloy artifacts in the Eurasian animal style. These objects complement the rock carvings from northwestern Tibet presented in the October and November newsletters, demonstrating that animal style art disseminated more widely on the Tibetan plateau in antiquity.

A Scintillating Visage: Another golden burial mask comes to light

Fig. 1. A prehistoric repoussé golden death mask, perhaps of western Tibet provenance (15 cm x 12 cm), pre-200 CE. Private collection.

Thanks to the efforts of the owner, another repoussé golden burial mask has recently come to my attention.* According to information received by the owner, this death mask was discovered in western Tibet. It is thought that the mask is made of solid gold. Whatever its precise metallurgical composition, this funerary mask is of exceptional value as an art and cultural-historical object.

For images and discussions pertaining to the golden burial masks of Upper Tibet, the high Himalaya and other Inner Asian regions, see October and November 2011 and November and December 2013 issues of Flight of the Khyung.The golden burial mask pictured here has been slightly crumpled, mildly distorting the facial features. Otherwise, this object is in fine condition. For lack of a better name, I will refer to this object as the “Volutes” mask, inspired by one of its prominent stylistic features.

Fortunately, the Volutes golden death mask can be compared to Inner Asian examples that I have previously studied. While a western Tibetan origin is plausible, we cannot discount the possibility that the Volutes mask came from an adjoining Himalayan region, somewhere in Xinjiang, or even further afield in Inner Asia. The six masks I have studied earlier (Chuthak, Gurgyam, Malari, Mustang, Shamsi, Boma) all have the benefit of an archaeological provenance and were recovered through scientific channels. The Volutes mask has no such provenance, detracting, at least for the time being, from its scientific value.

Fabrication from precious metal and their relative rarity indicate that the golden burial masks of Inner Asia are likely to have been used by highly accomplished warriors, chieftains or others of high social rank. This is the general pattern of usage wherever golden masks have been discovered worldwide. However, no detailed information regarding socioeconomic conditions reflected in the tombs that housed the four golden burial masks of Upper Tibet and the high Himalaya has been forthcoming.

It remains to be determined how often and it what ways ancient Upper Tibetans employed golden burial masks in their funerary rites. Golden masks or their facsimiles were of sufficient cultural prominence to be recorded in circa 11th century funerary literature of the Bonpo, where they are known as the ‘golden visage’ (sershe; gser-zhal). According to these sources, the golden visage is of ancient origins. It functioned to contain the soul of the deceased during the rite of evocation and the subsequent expelling of evil forces.

In many regions of Eurasia, from the Altai to Hungry, burial masks were alternatively made of silver, iron, clay, cloth and other materials. Perhaps there was a wider assortment of burial masks in the Tibetan-Himalayan region as well, but this remains to be ascertained.

By assessing their facial features and modes of fabrication, the six Inner Asian examples I have studied previously can be divided into three broad groupings: 1) Shamsi and Boma (circa 400–600 CE), 2) Mustang and Gurgyam (circa 300–500 CE), 3) Chuthak and Malari (circa 100 BCE to 200 CE). To this we can add another group consisting at the moment of just the Volutes specimen.

With its well developed, high relief facial features, the product of much skill in working sheets of gold; the treatment of the locks of hair and earlobes as volutes; and its zoomorphic undertones, I am inclined to attribute the Volutes golden death mask to an early period in Inner Asian metal mask production. As readers of the October and November newsletters will know (also see article, infra), a major animal style element in prehistoric Tibetan art is volute body ornamentation, which appeared no later than the developed Iron Age (circa 600–100 BCE). Like the earlier phase of animal style rock art in Upper Tibet, the Volutes mask appears to represent an original expression or adaptation of Inner Asian art, characterized by curvilinear forms of ornamentation. If indeed Upper Tibet and adjoining Himalayan regions, like Southeastern Europe and Luristan, used gold burial masks in the Iron Age, the Volutes specimen must be considered a potential candidate for such antiquity. In any case, this mask is best dated to the pre-200 CE period.

Wherever it was precisely made and deposited, the Volutes mask presents a number of unusual and unique features, making it especially intriguing. The same can be said for the other six Inner Asian masks: each one is absolutely unique. We might expect that all golden burial masks produced were envisioned as being as unique as the individuals who were fitted with them after death.

Let us compare the features of the six golden burial masks of Inner Asia that were the object of my earlier studies with the Volutes mask, in an attempt to better place the latter in a geographic scheme. Fashioned from a single sheet of metal of considerable thickness, the Volutes mask is punctuated with round eyes; the other six I have studied have oval or almond-shaped eyes. Round eyes are very unusual in Eurasian and Egyptian golden death masks (but more common in Pre-Columbian variants).

The Volutes mask and the Shamsi (Kyrgyzstan) and Boma (Xinjiang) specimens have pupils rendered by cutting holes in the metal. In the Shamsi mask, each pupil was filled with a piece of garnet. Likewise, precious stones or other substances may have once filled the pupils of the Boma mask and the larger openings of the Volutes one as well.

The slicing of the metal sheet to form eyes and brows is encountered in the Kalmakareh golden death masks of Luristan, dated to the first half of the first millennium BCE, but these are very different in appearance to the Volutes specimen. The golden death masks of the Late Bronze Age Jinsha and Sanxingdui cultures of the Sichuan basin also have eyes represented by open spaces in the sheet of metal. Nevertheless, the Chinese golden masks strongly contrast in form, style and function to the Volutes mask. The Sanxingdui and Jinsha masks were fitted onto bronze effigies.

Six of the seven Inner Asian masks treated in this article are marked with arched eyebrows (this painted anatomical feature has been effaced on the Mustang specimen). All of the golden burial masks under examination, except the Malari example (it has flaring nostrils), have long, thin noses. This shape of nose is suggestive of a Caucasoid physiognomy.

The Volutes mask is depicted with a wide open mouth fashioned from a large aperture in the sheet of gold. An upper set of teeth was also cut into the metal (the Gurgyam mask has a full set of painted teeth). The cutting of the sheet of metal to form a mouth is rare in Eurasian and Egyptian golden death masks, but is found in a Javan example from the pre-6th century CE and in Pre-Columbian specimens.

It is sometimes claimed that the creation of the Sanxingdui and Jinsha golden burial masks was inspired by those of ancient Egypt and Mycenae. It is difficult to posit such a source for the genesis of Tibetan-Himalayan masks, however, as none of the extant examples can be shown to be of Bronze Age antiquity. It is also held by some scholars that Central Asian burial masks of the first millennium CE came about through Hellenistic influences moving eastward via Parthia and Bactria.*However, this spatio-temporal pathway cannot directly account for the earliest groups of Tibetan-Himalayan death masks. If these masks were the result of Hellenistic cultural influences, they belong to an antecedent period of propagation. Yet, such a historical scenario throws up a formidable problem: Hellenistic funerary materials perforce would have entered north Inner Asia or the northern Indian Subcontinent before transferring to the more remote Tibetan plateau, but golden burial masks of requisite antiquity do not appear to be known in areas immediately north and west of Upper Tibet. Wherever the ultimate source of cultural inspiration for the Tibetan-Himalayan golden death mask lies, it is clear by their styles that they are largely the product of indigenous artistic and artisanal traditions.

For this theory, see M. Benkő, 1992,1993: “Burial masks of Eurasian mounted nomad peoples in the migration period.(1st millennium A. D.)” in Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, vol. 46, (2– 3), pp. 113–131. This paper examines the spread of burial masks, face-covers and eye-covers over a wide cross-section of Eurasia in the first millennium CE, and through the ethnographic record, it reviews survivals of these funerary customs into the 20th century.The Volutes golden burial mask appears to be the only one of the Inner Asian examples I have studied in which ears are distinctly fashioned. Iron Age Etruscan and Thracian masks and the older Mycenae golden death masks often have ears depicted. The earlobes of the Volutes specimen are simulated by volutes, recalling a prime motif of Inner Asian animal style art (see October and November 2014 Flight of the Khyung).

The Volutes golden death mask is the only specimen to have an inwardly projecting jaw among the seven Inner Asian examples discussed here (the other ones have a rounded jawline). Moreover, the Volutes mask is the only Inner Asian example with hair depicted (hair is commonly portrayed in Thracian masks). The two locks of hair on the Volutes mask form simple volutes. The almost pentagonal facial outline of the Volutes specimen is seemingly unique among golden burial masks (the other six Inner Asian specimens discussed in this article have more or less oval faces).

All four Tibetan-Himalayan masks enumerated in this article have a series of small perforations along the edges, which functioned to attach a textile face-cover or shroud (as seen in the Chuthak example). Like the depiction of ears and cut out mouth, the absence of attachment holes, sets the Volutes mask apart from those of confirmed Upper Tibetan or Himalayan origins.

Taken in total, the facial features of the Volutes golden death mask convincingly point to an Inner Asian provenance; either south Inner Asian (Tibet, Himalayan rim-land) or north Inner Asian (Xinjiang, Kyrgyzstan, etc.). The volute designs of the hair and earlobes and the shape of the nose are key esthetic traits in making this determination.

Furthermore, some of the physiognomy of the Volutes golden death mask resembles certain kirtimukha (‘glorious face’), a therio-anthropomorphic creature commonly found on Tibetan objects from no later than the imperial period (circa 650–850 CE). This encourages a more refined attribution of the Volutes mask to the Tibetan plateau or adjoining Himalayan tracts, supporting the report received by the owner concerning its provenance.

Fig. 3. A Tibetan thokcha with a kirtimukha surmounted by the smaller head of another creature. Circa 400–900 CE: late portion of the Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 600 CE) or imperial phase of the Early Historic period (600–1000 CE). Private collection.

Fig. 3 depicts a copper alloy object with a kirtimukha in the middle, possessing traits paralleling those of the Volutes golden burial mask. The lion-like countenance of the thokcha has a five-sided outline with an inwardly projecting jawline, just like the mask. The mask and thokcha also share in common round eyes, curved eyebrows, rather long noses, and an upper row of teeth (barely visible on the thokcha). Instead of volutes of the earlier period, the top of the head of the kirtimukha is ornamented with wavy lines. The upper head of the thokcha is feline or apelike in character. In early zoomorphic thokcha heads of this kind are quite common, often as a crowning or central element of the object. These heads must represent protective deities of some stripe. The object pictured in fig. 3 may possibly be an ornamental component of horse tack. For other examples of this class of objects, see fig. 9 below; and August 2014 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 5.

Comparative features of the Volutes mask and kirtimukha suggest that prototypes of this creature existed in Tibet centuries before the imperial period. As with the lion, we might therefore conclude that the introduction of the kirtimukha in Tibet constituted the blending of a well-rooted artistic tradition with ones issuing from Iran or India during the Tibetan empire period. Similarly, the horned eagle (khyung) of Lamaism represents a mingling of indigenous and Indic artistic and cultural traditions.

Although, attribution of the Volutes golden death mask to western Tibet is plausible, positive confirmation of its geographic origin will only come about with the acquisition of additional archaeological and art historical data.

Serpentine Signs: Tibetan copper alloy artifacts with animal style motifs

If the Upper Tibetan (and Ladakh) petroglyphs examined in the previous two issues of Flight of the Khyung were the only archaeological material available for the study of this branch of Eurasian animal style art, we might conclude that it did not penetrate beyond the western fringe of the plateau. However, animal style rock art has also been recorded in northeastern Tibet, in what is now the provinces of Qinghai and Gansu.

The animal style rock art of northeastern Tibet is closer in tone and form to north Inner Asian variants than are the petroglyphs of Upper Tibet, suggesting that cultural and demographic influences of the steppes were felt more strongly in northeastern Tibet. Northeastern Tibet has long been a conduit between greater Mongolia and the more central regions of Tibet. For more background on the animal style in northeastern Tibet, see L. Bruneau and J. V. Bellezza, 2013: “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’” in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28, pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS: http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf

Another source for animal style art in Tibet are the copper alloy objects known as thokcha (thog-lcags), a heterogeneous class of talismanic, ritual, decorative and utilitarian objects. I have spent many years photographing thokcha, visiting collectors in various parts of the world to augment my photo archive. Four of the images shown below are from such labors (all with scale in centimeters). To my knowledge, two or three of the thokcha examined below comprise the only examples of prehistoric Tibetan animal style objects published to date.

While there are many different kinds of early zoomorphic thokcha, animal style examples appear to be rare. This indicates that while the animal style spread beyond the northwestern and northeastern corners of Tibet, it remained a relatively minor genre of art on the plateau. From this, we can conclude that Tibetans of the Iron Age (600–100 BCE) and Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 600 CE) generally preferred native styles of rock art and copper alloy objects to more cosmopolitan strains. Like the rock art of Ruthok, copper alloy objects in the animal style are distinguished by three types of curvilinear body ornamentation: single volutes (front and rear), double volute or scroll and the S-shaped motif.

Fig. 4. A circular fibula decorated with a band of S-shaped designs. The rim of the object is knobbed and has four pointed extensions. Inside the inner ring is a small slot (at the top), which presumably accommodated a pin used to attach the fibula to an item of clothing. Protohistoric period. Private collection.

We can be confident that such fibulae, which come in many styles and sizes, were produced on the western part of the Tibetan plateau (including Ladakh). This is borne out by their consistent discovery in that region, where they are kept as heirlooms and where they are excavated from time to time. A number of fibulae have been published, but none with the S of the animal style.* Fibulae were manufactured on the western Tibetan plateau in the Protohistoric period and in the Early Historic period (boasting motifs such as the dorje or thunderbolt of Vajrayana Buddhism). Given that animal style rock art and the fibula under discussion come from the western Tibetan plateau, we can hypothesize that the S motif was communicated between various media, as a symbol, emblem or decoration of considerable cultural currency. The Volutes golden burial mask discussed above may well add even more weight to curvilinear ornamentation in prehistoric Tibet.

For fibulae, see:Bellezza, J. V. 1998. “Thogchags: Talismans of Tibet” in Arts of Asia, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 44-64. Hong Kong.John, G. 2006. Tibetische Amulette aus Himmels-Eisen. Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf.

Tucci, G. 1973. Transhimalaya (trans. J. Hogarth). Reprint, Delhi: Vikas Edition.

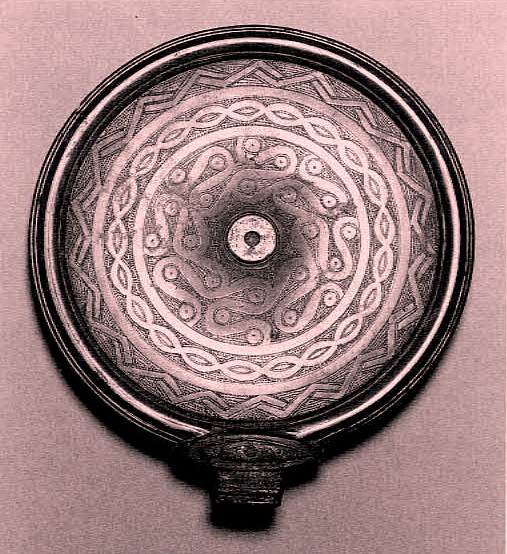

Fig. 5. An engraved copper alloy mirror of Tibetan manufacture with a complex volute pattern in the center. Iron Age or early Protohistoric period. Former collection of the late Namgyal G. Ronge. Digital image after Ronge 1990 (see below for bibliographic details).

Fig. 6. A Tibetan engraved copper alloy mirror with volutes of the Ruthok animal style in the outer ring. Iron Age or early Protohistoric period. Former collection of the late Namgyal G. Ronge. Digital image after Ronge 1998 (see below for bibliographic details).

The prevalence of curvilinear designs in ancient Tibet is strengthened yet further by the two rare copper alloy mirrors pictured above.* They each boast engraved volutes. These objects were part of the late Namgyal G. Ronge collection of thokcha (many of which appear in John 2006; see bibliographic details above). The mirror in fig. 5 sports an intricate pattern of interconnected volutes and interspersed ‘eyes’ (mig) engraved in the inner circle. The central circle of this mirror is circumscribed with a chain of ovals, each with an ocular design in the middle. The outer circle consists of a ring of overlapping triangles. The copper alloy mirror in fig. 6 is of the same type. The outer circle is engraved with volutes of the form encountered in Upper Tibetan animal style rock art. The central circle consists of a band of diamonds and the inner circle is embellished with six separate concentric rings. Ronge notes that this mirror was allegedly found in the western Tsangpo valley.

For these mirrors, see:N. G. Ronge, 1988: “Thog-lčags of Tibet” in Proceedings of the 4th Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies. Schloss Hohenkammer – Munich 1985 (eds. H. Uebach and J. L. Panglung), pp. 405-412. Munich: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften.N. G. Ronge and H.-G. Hüttel, 1990: “Ein eisenzeitlicher Spiegel aus Tibet”, in Beiträge zur allgemeinen und vergleichenden Archäologie, vol. 9-10, pp. 225–241. Mainz.

Also, see A. Heller, 1998: “Two Inscribed Fabrics and their Historical Context: Some Observations on Esthetics and Silk Trade in Tibet, 7th to 9th Century.”, in Entlang der Seidenstraße: Frühmittelalterliche Kunst zwischen Persien und China in der Abegg-Stiftung. Riggisberger Berichte 6 (ed. Karel Otavsky), pp. 95–118. Riggisberg: Abegg-Stiftung.

Both of the engraved mirrors are dated by Ronge to 800–300 BCE. Heller instead dates the first specimen discussed, supra, to 200 BCE to 200 CE. While I believe an Early Iron Age date for these objects is probably too early, an assignment between 500 BCE and 200 CE (Iron Age or early Protohistoric period) seems warranted.

As for their place of manufacture, it is plausible that they were made somewhere in Upper Tibet or Ladakh (despite the first one discussed above turning up in Kongpo, in the 1980s). I base this attribution on the recent appearance of a third engraved mirror of the same type in Lhasa (albeit less well preserved), which is said by the owner to have been discovered in northern Ruthok. That two of the three mirrors are associated with Upper Tibet seems significant in itself. Moreover, interlinked volutes are a central motif in the animal style rock art of Ruthok. Placement of the engraved mirrors in Upper Tibet is reinforced by the fibula from the western Tibetan plateau with embossed S-shaped designs examined above. Verification of the geographic origins of the engraved mirrors, however, will only be gained through further archaeological and art historical study.

Fig. 7. A copper alloy mirror (melong) embossed with three concentric bands of animals. The mirror is 13 cm in diameter. Iron Age or early Protohistoric period. Private collection.

This important figured mirror boasts four types of animals: 20 hares and a frog-like creature (outer circle), six wild yaks (middle circle) and three unidentified animals (elephant?) (inner circle). The two inner circles have a combined diameter of 6.5 cm. According to the owner, this mirror was discovered in Nagchu prefecture (much of which falls in the Changthang). The legs, body shape and front and rear volutes of the embossed yaks bear a strong similarity to a wild yak petroglyph from Lushan, Qinghai.* The Lushan yak, however, has a raised and more rounded tail and more curved horns. Like the yaks, the outer band of hares also have front and rear volutes. Hares are a common subject in Ordos bronzes but are uncommon in Tibetan thokcha.

See Tang Huisheng and Zhang Wenhua, 2001: Qinghai Yanhua: shiqian yishu zhong eryuan duili siwei ji qi linian de yanjiu (Qinghai petroglyphs: opposition and unity: a study of Shamanistic dualism in prehistoric art -a decipher of the petroglyphs). Beijing: Science Press. Color plate 14, at rear of book.The volutes adorning the animals and the hares betoken esthetic and cultural influences emanating from north Inner Asia, which may have entered the plateau via its northeastern flank. The stylistic traits of the embossed animals and the putative discovery of the mirror in Nagchu suggest that it was made somewhere in Nagchu or perhaps in Amdo, as an example of Tibetan animal style art. A Tibetan origin for this object is buttressed by other features including two rings of nubs flanking the band of hares, a form of ornamentation seen on other early figured mirrors and fibulae of Tibetan origins. The style of the three attachment rings at the top of the mirror also has a Tibetan look about it. This type of appurtenance is not encountered in mirrors of Scythian or Chinese or manufacture.

Fig. 8. A copper alloy plaque, badge or equestrian ornament with horse (identified by its long neck, full tail and the general form of the body). Iron Age or early Protohistoric period. This object was purchased in Shigatse in the early 1990s and formed part of a now disbanded collection (see Arts of Asia, May-June 1998).

This object is most likely to have been made in Upper Tibet or Central Tibet. The horse, head regardant, sports two wheels or circles on its flanks. Each wheel is designed with two or three concentric circles situated inside an outer ring with gear-like protrusions. These discs may possibly represent the sun and moon. We can view them as an esthetic extension or alternative to volute ornamentation. Another animal style feature is the raising of the lead leg. The stolid but bold aspect of the horse is characteristic of early Tibetan art. The horse is bordered by a rectangular frame decorated with nubs and parallel lines. Geometric designs are often seen on thokcha produced prior to 1000 CE.

Fig. 9. A copper alloy object featuring a lion, which may be a kind of ornamental horse tack. Late Protohistoric period or Early historic period. Private collection, UK.

The lion in the center of the object displays the double volute motif (part of the rear portion has worn away). Mouth open, as if roaring, a portion of the tail and mane are also visible. The two front legs and one of the rear legs can be seen as well. Between the lion and outer ring are three kidney-shaped open areas in which cords may have once passed. The outer ring is marked in three places with foliate flourishes. This probable white bronze (li-dkar) object may have possibly adorned a horse harness. For another example of the same class of objects, see fig. 3 above, and August 2014 Flight of the Khyung.

If this object is indeed from the Early Historic period, it shows that the double volute motif persisted as a relict artistic trait during Tibet’s imperial rise. However, most curvilinear body adornment of this period evolved into alternative forms.* Vestigial curvilinear body designs and heads of animals turned back to face the body are found in thokcha and other objects and pictorial art fabricated even in the second millennium CE. The most recent echoes of the animal style are seen in the work of contemporary blacksmiths in eastern Tibet.

For example, there are silver saddle ornaments in the form of horses and ibexes of the imperial period, in which the volute is both elaborated (horses) to the extent that it resembles a floral pattern and attenuated to the point of becoming parallel wavy lines on the belly of the animal (ibex). These saddle ornaments and others from the same equestrian ensemble (Pritzker collection) reveal a cosmopolitan style of art favored in Tibet of the empire period, one with Sogdian, Turkic, Tang, Sassanian, Sogdian and Newar influences. For this saddle and harness, see A. Heller, 2003: “Archaeological Artefacts from the Tibetan Empire in Central Asia.”, in Orientations, vol. 34 (4), pp. 55–64 (go to pp. 57–59). Heller proposes that the saddle and harness belonged to a Tibetan general or statesman and can be dated to the second half of the 8th or 9th century CE. The saddle and harness, grave objects, were probably part of valedictory funerary rites.It can be observed that while tigers regularly occur in the rock art of Upper Tibet, lions portrayals are rare. On the other hand, lions are a popular subject in thokcha. Tiger thokcha, however, are not very common. Why lions were popular to wear and display and tigers to carve is not entirely clear. However, chronology plays a part. Most tiger petroglyphs belong to the prehistoric epoch (pre-7th century CE), while most leonine art dates to the historic epoch (post-6th century CE). Although Protohistoric period lion thokcha are known, they become much more common in the Early Historic period, probably as part of imperial conquest and the reopening up of the Tibet to the wider Eurasian world (lions do not appear to be indigenous to the ancient plateau). In many ancient cultures of the continent, lions were a symbol of regal power and military strength. Tiger rock art is also a marker of cosmopolitan activity, but of an older variety. In the Iron Age, tiger art spread across Inner Asia.

A Further Note on the Tibetan Animal Style

This note reviews a work by George N. Roerich, 1930: The Animal Style: Among the Nomad Tribes of Northern Tibet (24 pp.). Prague: Seminarium Kondakovianum. This innovative study still has much value and relevance to our own inquiries in the 21st century. For a digital copy of this work, see the website of the Nicholas Roerich Estate Museum, Isvara:

http://www.roerich-izvara.ru/eng/roerich/george-roerich-animal-style.htm

During the Central Asiatic Expedition (1925–1928), which was led by his father, the famous painter and spiritualist, Nicholas Roerich, George Roerich found traces of animal style art among nomadic communities in northern Tibet. He believed that tribes from the Koko-Nor (Tsho-sngon) region of Amdo traveled south until they confronted the Transhimalayan ranges, which deflected their migrations westward through Nagchu, Namru and beyond to Mount Tise, in southwestern Tibet. Roerich maintains that it was these peoples who brought the “highly conventionalized” animal style art of Central Asia to regions of Upper Tibet.

In his article, Roerich further propounds that after the Yüeh-chih were expelled [from the eastern Tarim Basin] by the Xiongnu in the 2nd century BCE, a splinter group that became known as the ‘Little Yüeh-chih’ found refuge in the Nan Shan (Qilian Mountains), where they mixed with autochthonous Tibetan tribes. According to Roerich, it was the resultant amalgamation of peoples that was responsible for the spread of the animal style in Tibet. Roerich identifies zoomorphic ornamentation found on flint pouches, belts, plaques, scabbards, charm boxes and other things as being derived from Scytho-Siberian art. Roerich adds that well-known Tibetan animal style subjects include deer, antelopes, birds and fantastic creatures.

As I have shown, in the October and November 2014 newsletters, animal style art in western Tibet reveals cultural affinities with Ladakh and Xinjiang. Therefore, postulating a single geographic wellspring for the animal style in northeastern Tibet is not substantiated. Had this been the case, we should be able to find animal style rock art in Upper Tibetan regions other than the far west alone. Roerich’s pioneering study does not include ancient animal style objects or rock art, which limited his ability to document the spread of the animal style in Tibet over the last 2500 years.

A thokcha featuring a double-headed eagle obtained by the Roerichs west of Nagchu is compared to finds from the Kuban barrows of the northern Caucasus and traced even further back in time to the Hittites. Although the copper alloy double-headed eagle inside a ring obtained by Roerich is crudely depicted, well modeled (and probably older) double-headed eagles are indeed found among the thokcha of Tibet. While the specific vectors of geographic diffusion and spheres of stylistic transformation are still obscure, as Roerich suggests, such thokcha do point to interactions with the wider Eurasian world.

Contemporary ‘animal style’ art in Tibet intimates a long process of change and adaptation within Tibet. This is clearly demonstrated by a historical survey of Tibetan zoomorphic art. Thus, the contemporary animal style does not merely represent the survival of a Scytho-Siberian art form unchanged since the first millennium BCE.

At this juncture in our inquiries, there is no one tribe or event of prehistoric north Inner Asian origin that can be held solely responsible for the propagation of the animal style in Tibet. In fact, a cosmopolitan genre of art introduced in the Tibetan imperial period (circa 650–850 CE) referred to above is likely to have as much or more to do with the development of the contemporary animal style in Tibet than the Scythians* themselves. The resemblance of contemporary Tibetan zoomorphic motifs to Scytho-Siberian ones was probably largely mediated through Sogdian, Turk and/or Sassanian artistic influences that permeated Tibet. These foreign traditions of zoomorphic figuration of course borrowed from preexisting north Inner Asian esthetic traditions, which were then passed along to Tibet, beginning in the 7th century CE.

Properly applied, ‘Scythian’ is a generic term for various Iron Age peoples who adopted analogous technological and artistic traits, and who spread widely in Eurasia. In George Roerich’s time, the term ‘Scythian’ often denoted a super tribe with a relatively homogenous ethnic and cultural makeup. More recent research demonstrates that no such singular group can account for the great variability that exists in the archaeological record of the Eurasian steppes and surrounding deserts and mountain ranges.Hence, Tibet and Inner Asian / Central Asian cultures of the imperial period appear to be heirs to styles of art separately and vis-à-vis one another that are ultimately attributable to the Scythians, a source of esthetic inspiration that mingled and remingled over the centuries in objects produced in the middle of Eurasia.

Special Note for Readers

Over the last thirty years, a large amount of pre-Buddhist art and artifacts has been removed from Tibet, but most of it has disappeared, never to see the light of day again. Where is it all? Stored away in draws and closets and in attics and cellars or hung on walls are objects of exceptional importance to the study of Tibetan archaeology and cultural history.

If you the reader know of any pre-Buddhist Tibetan artifacts or art held by dealers, museums or private collectors, or that was casually or inadvertently obtained, please consider letting me know. I am very interested in receiving photographs and any information that one may like to share about ancient Tibetan objects that are not Buddhist. If owners would like to feature such things here in Flight of the Khyung, that should be possible. I very much look forward to hearing from you.

Next Month: The Sad Tale of the Destruction of Priceless Buddhist Frescoes in Guge and more!