August 2016

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to the tenth anniversary edition of Flight of the Khyung, your portal to the ancient wonders of Tibet! This is the 121st monthly newsletter, bringing you all things Tibetan since August 2006.

I began Flight of the Khyung a decade ago with generally short newsletters more in the style of a blog. In the early issues I informed readers about my scholarship, shared views on sundry matters (Tibetological and otherwise), posted excerpts from personal journals, and retold my adventures in Tibet and the Himalaya. As the years passed, Flight of the Khyung became more scholarly and formal in style. Along the way I realized that if I was to write up all my findings from Tibet this newsletter would have to become a scholarly forum. Although I have of course continued to publish books and articles, these digital pages have emerged as an essential supplement to my scholarship.

This 10th anniversary issue of Flight of the Khyung presents the second part of an article on wild yak hunting in the rock art of Upper Tibet. In this issue there is a gallery of stunning images of ancient hunters contending with one of the largest and fiercest land mammals on earth. Whether as prey or as a symbol of the supernatural, Upper Tibetans sought to record in stone their exploits with the wild yak. There is hardly a more stable and endurable medium than carvings and paintings on stone, a portal to the amazing world of prehistoric Tibet.

Bravery, Propitiation and Accomplishment:

Wild yak hunting in the rock art of Upper Tibet – Part 2

Note: For the initial sections of this article and the bibliography, see last month’s newsletter.

Part 2 of this article is divided in the following subsections:

- Solitary horsemen directly confronting wild yaks

- Solitary horsemen chasing wild yaks from the rear

- Solitary horsemen in association with wild yaks and other animals

Chronological terminology used in this work:

Late Bronze Age: ca. 1500–700 BCE (differentiation between late Bronze Age and early Iron Age omitted due to lack of data)

Iron Age: ca. 700–100 BCE

Protohistoric period: ca. 100 CE to 650 CE

Early Historic period: ca. 650–1000 CE

Solitary horsemen directly confronting wild yaks

We begin this part of the picture gallery with rock art (petroglyphs and pictographs) depicting the hunting of wild yaks by solitary hunters (figs. 11–49). The first five compositions illustrated feature mounted archers confronting wild yaks head on. This Upper Tibetan rock art can be attributed to the Iron Age. The rarity of this kind of scene is probably explainable by the great risk a hunter would incur by coming face to face with a wild yak.

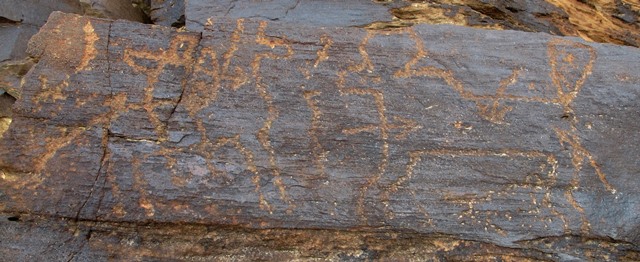

Fig. 11. An archer on horseback pointing his bow and arrow at a charging wild yak, western Changthang. Iron Age.

In this composition the horseman is silhouetted and the wild yak outlined.* Both of these modes of carving are well represented in the hunting rock art of Upper Tibet. The hunter aims his bow directly over the head of his horse in a frontal assault. The arrow point is disproportionately large, accentuating its killing power. Lines carved on the anterior portion of the wild yak’s body may depict arrow strikes, implying that the doomed animal is experiencing its last gasp of life. The legs of the hunter hang below the body of the horse. What could possibly be baggage is shown behind the hunter. Hunters would have needed basic supplies to sustain them during yak hunting expeditions. The wild yak at twice the length of the horse is shown larger than life size, enhancing the personal and social achievement encapsulated in the hunt (see last month’s newsletter for a discussion).

For this composition, also see Bellezza 2001a, pp. 133, 208 (fig. XI-4c); 2008, p. 176 (fig. 312).

Fig. 12. Horseman confronting a wild yak, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

It is not clear if the head of the horse or an arrowhead or both are depicted in this highly re-patinated composition. One of the arms of the figure is drawn back, a typical mode of portrayal in wild yak hunting scenes, suggesting that he is an archer. Above the wild yak is what might be a hunting dog, a fairly common accompaniment to such scenes. It is also possible though that this long-bodied figure with pointed ears is a prototypic zoomorphic functionary in the form of a wild carnivore, shown as a symbolic or mystic part of hunting activities. Other interpretations may also be entertained. Without further evidence, it is prudent to not identify this subject too narrowly.

Fig. 13. Deeply carved horseman facing a wild yak, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

Details are lacking in this composition, but given its general aspect, it can be assumed that the horseman is armed with a bow and about to dispatch the wild yak. The square extension on the back of the wild yak appears to be its hump.

Fig. 14. Face to face encounter between mounted archer and wild yak, central Changthang. Iron Age.

In this composition we once again see a mounted archer attacking a wild yak head on. As in many wild yak hunting scenes in Upper Tibet, the bow and arrow are rudimentary in form. The horse and rider are portrayed relatively large, perhaps in a demonstration of mastery over the prey. The less re-patinated wild yak in the bottom right corner of the image is not part of the same composition.

Fig. 15. An archer on horseback attacking a wild yak from up front, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

In this scene the rider shoots directly at the wild yak from around the horse’s neck. The quarry is already shown impaled by two arrows (one in the chest and one in the back). There can be no question that this composition portrays the hunter coming in for the final kill. The horse has a long tail and wedge-shaped object on its rear that may be part of the horse tack (cantle?). The tail of the wild yak forms an inverted triangle, one raised in great fear.

It is very unlikely that horseman could have chased wild yaks at this location in far western Tibet. This rock art is situated on a steep, boulder-strewn slope unfit for horse riding. Such geographic conditions exist at certain other sites with wild yak hunting rock art in far western Tibet. These scenes therefore appear to chronicle hunting expeditions in other places in Upper Tibet. Much rock art in far western Tibet was made near winter campsites and more permanent settlements, affording hunters adequate time for creating petroglyphs.

Solitary horsemen chasing wild yaks from the rear

In the wild yak hunting rock art of Upper Tibet, it is most common for mounted archers to be depicted approaching their prey from behind. In all parts of Upper Tibet and in all phases of wild yak hunting rock art production, this type of theme constitutes a conventional arrangement, a pictorial trope embracing the social, personal and political elements discussed in Part 1 of this work.

Coming at wild yaks from the rear would expose hunters to less risk than pursuing them head-on. Although all the scenes illustrated below depict only one hunter, they are likely to express the culminating part of the wild yak hunting experience. Save for a wild yak being so spooked that it did not attempt to hold its ground from a lone hunter and horse, it is implicit in these scenes that other personnel participated in the hunt. In order to create the opportunity for a single hunter to close ranks on wild yak from the rear, other horsemen would in all likelihood be required to drive and harry the animal from various positions (this is amply demonstrated in the group hunting rock art featured in Part 3 of this article). A wild yak could be overwhelmed in this manner, permitting one of the hunters to approach it from behind. As already discussed, the depiction of a single hunter making the kill served as a medium for highlighting the virtues and prowess of a specific individual.

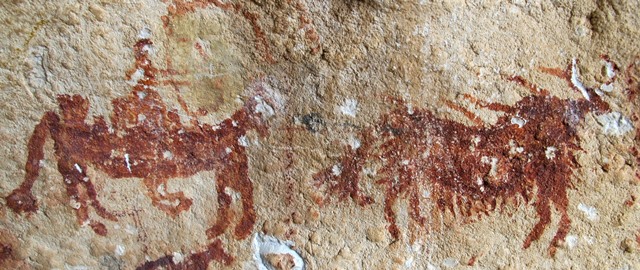

Fig. 16. Mounted bowman killing wild yak from behind with an unfinished and a larger wild yak below, eastern Changthang. Iron Age.

This rock art with its bold lines and sharp angles belongs to an early phase in the making of pictographs.* It was painted using an ochre with a magenta hue. The upper wild yak has already been hit with an arrow in the front haunches, confirmation that the hunter is successful. The different colored tail of the horse may have been painted subsequently. The larger upper and lower wild yaks have arched lines designating the front and rear haunches of the animals. The lower specimen is unmolested by the hunter’s arrows. Perhaps it was created as a symbol of or tribute to the great stock of wild yaks in the region. The middle wild yak appears to belong to the same composition but was never finished. The small cave in which this rock art is found pullulates with pictographs, so it is not always possible to determine the scope of integral compositions. The birdlike lighter red-colored subject in the middle of the composition was added later.

For this composition, also see Suolang Wangdui 1994, p. 140 (fig. 172); Bellezza 2002b, p. 365 (fig. 9).

Fig. 17. Mounted archer chasing wild yak with another animal below, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

There are a number of carvings on this flat-topped boulder, but this scene forms a semiautonomous vignette among them.* The unfinished bow of the hunter is raised above the head of his mount. The other animal in the composition may be a hunting hound or possibly another wild yak.

For the rock carvings on this boulder, see Part 3 of this article, fig. 54; Bellezza 2001a, pp. 141, 237 (fig. XI-5f).

Fig. 18. An archer on his horse chasing a wild yak from behind, eastern Changthang. Iron Age.

The wild yak has already been struck by one or more arrows from the hunter’s bow. The two figures of this composition were painted as a series of slashes to create the hair, mane, horns, ears, tail, and fur pattern of the animals, and hunter. The horseman is drawing his bow, his legs dangling below the belly of the horse. He may possibly be depicted with a quiver at his side.*

For this figure, also see Bellezza 2002b, p. 364 (fig. 6).

Fig. 19. Horseman pursuing wild yak, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

Although the bow of the hunter is not fully manifest, there can be little doubt that he is deploying this weapon against the wild yak. The bent legs of the horse and wild yak divulge that they are running. The wild yak has unusually long horns and is mainly identified by the shape of its tail.

Fig. 20. Mounted archer and hound chasing a wild yak. Another wild yak in the same basic style is situated to the right, western Changthang. Iron Age.

Both wild yaks have a wedge-shaped tail, triangular legs, barbed belly, and silhouetted hump, etc. In this composition we have a good indication that dogs were used in coursing wild yaks. Perhaps another canine is intended by the small carving between the two wild yaks.*

For this composition, also see Bellezza 2001a, pp. 133, 208 (fig. XI-1c).

Fig. 21. Bowman on horseback closing in on a relatively small wild yak, western Changthang. Iron Age.

This scene is now familiar to us, only the style varies. Each artist created a unique record of his own exploits or possibly those of others according to his artistic skill and inclination. In this example, the carver devoted much care to the creation of the horse and rider. The hunter appears to be wearing a robe gathered at the waist and hitched up above the knee. The arched line below the rider’s feet may possibly represent a rope stirrup. The two lines protruding from the neck of the horse may be arrows at the ready. The archer is aiming directly at his prey. The protrusion on the back of the wild yak may represent an embedded projectile.

Fig. 22. Mounted archer shown in the perspective of shooting his arrow at a wild yak from the side. To the right of the quarry is possibly another mounted hunter, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

The pyramidal shape of the torso of the rider suggests that he is attired in a long robe. The highly unusual feature of this composition is that the archer appears to be riding a yak (one larger than the quarry itself). The horns, hump and belly fringe of his mount are recognizable. This raises questions as to the nature of the scene. Possibly it represents a divine hunter mounted on a spirit animal. Or perhaps yaks were once used for hunting wild yaks. If so, this would be a heretofore unknown function connected to the domestication of the bovid in Upper Tibet. There are several other figures mounted on wild yaks in the rock the of Upper Tibet but they are not associated directly with the slaying of animals. These scenes seem to portray numinous figures (see July 2012 Flight of the Khyung; also Part 3 of this article, fig. 111).

Fig. 23. Mounted archer attacking wild yak, western Changthang. Iron Age.

Carved in a rudimentary but effective style, this pair of figures is located on a boulder with many other wild yak hunters and is part of one or more composite hunting scenes. That individual hunters approaching wild yaks from the rear were part of a larger hunting strategy involving a group of participants is confirmed by this complex rock art.

Fig. 24. Mounted archer and wild yak, central Changthang. Iron Age.

The bowman has been reduced to a cruciform figure with the arch of the bow also signified. The mount and the wild yak were realistically portrayed.* This is yet another scene of hunter and hunted, a deadly symphony of activity played out again and again in the ancient rock art of Upper Tibet.

For this composition, also see Suolang Wangdui 1994, p. 125 (n. 141).

Fig. 25. Wild yak and what appears to be a horseman in pursuit, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

Part of the head of this boldly carved wild yak was lost when the rock panel was broken. The mounted archer (if that is what it is) has been stylized to take on bird-like qualities. There are no signs of weapons in this petroglyph, so attribution as a hunting scene is provisional.

Fig. 26. Horseman with bow slaying wild yak from the front, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

This composition is the only one that can be attributed to the Protohistoric period which shows a frontal assault on a wild yak. There are around ten other carvings of animals and other figures on the same rock panel but apparently no other hunters. Some of these figures were probably carved by the same artist as the hunting composition. The wild yak has already been struck in the chest by an arrow. Perhaps the small carving between the horseman and wild yak depicts an arrow in flight. The hunter is aiming yet another arrow at his prey.

Fig. 27. Mounted archer dispatching a wild yak, eastern Changthang. Protohistoric period.

In this adeptly executed red ochre composition the wild yak has been struck in the back by two or three arrows. The horse is depicted galloping as its rider finishes off the wild yak with another arrow. The saddle has a high cantle and pommel. Possibly, stirrups are also depicted, but the identity of the wedge-shaped object on the back of the horse is unclear. As in figs. 21 and 23, the horse has a ball of fur at the end of its tail.*

On this rock art and many adjacent pictographs, see Suolang Wangdui 1994, p. 139 (fig. 169); also see Bellezza 2002b, p. 366 (fig. 10).

Fig. 28. Mounted bowman shooting at wild yak from the rear, eastern Changthang. Protohistoric period.

The bow and arrow of the hunter are clearly represented. The saddle of the rider may also be depicted. The wild yak is somewhat obscured by wear and the running of other pigment applications. This composition is tightly packed among other pictographs in the same cave as fig. 16.

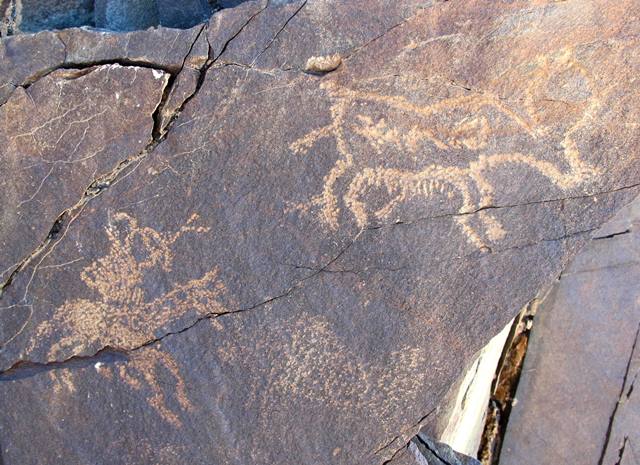

Fig. 29. Mounted archer shooting at wild yak, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

The hunter’s arrow appears to be forked, perhaps a depiction with symbolic undertones. The body of the wild yak is ornamented with a double volute, a defining trait of Eurasian animal art in Upper Tibet. The relative re-patination of the figures illustrated suggests that the wild yak immediately to the right of the horseman was engraved at a later date.

Fig. 30. Mounted archer and carnivore attacking a wild yak, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

These deeply carved figures are amid others situated on the same rock art panel of an outcrop marking a constriction in a valley. The theme is now very familiar to us: an archer shooting his bow as he approaches a wild yak from the rear. The exaggeratedly large arrowhead of the hunter conveys the effectiveness of the weapon. The S-shaped tail of the accompanying carnivore is more feline than canine. If a wild animal is intended here, rather than a hunting dog, this figure may possibly be a spirit helper or prototypic symbol of the hunter.

Fig. 31. Mounted archer aiming at wild yak, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

As in some other places in far western Tibet with such scenes, wild yak hunting on horseback was not practicable at this site due to the difficult terrain. The bowstring of this composition is bent in a peculiar way. A smaller third animal was engraved just above the wild yak. In this composition, the hunter is almost upon the wild yak in a demonstration of talent and courage.

Fig. 32. Horseman chasing wild yak, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

Although the bow and arrow of the hunter are not clearly visible, it can be inferred that this is a typical Upper Tibetan wild yak hunting scene. The horse is nearly in contact with the wild yak in a customary display of hunting skill. Like other conventional depictions, this one maximizes the qualities of the hunter thought most attractive.

Fig. 33. Mounted archer shooting at wild yak, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

This composition is situated at the same site as fig. 32, on the eastern fringe of the Karakorum. It possesses all the basic features of wild yak hunting in which a rider approaches the beast from behind. The hunter is bearing down on the wild yak in an expression of aptitude and bravery.

Fig. 34. Mounted bowman coming in for the final kill, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

In this variation of the conventional theme, the advancing hunter is still some distance from the wild yak. Nevertheless, this is a viable deployment, given the range of the bow and arrow and the dangers posed by the animal. There is another mounted hunter lightly engraved directly below the wild yak. The wild yak has an exaggeratedly large bushy tail.

Fig. 35. Hunter approaching wild yak from the side while firing an arrow, western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

The wild yak has already been impaled in the neck by a long arrow, depicting the demise of the beast and the triumph of the hunter. It is unusual in the rock art of Upper Tibet for a solitary hunter to be portrayed shooting his prey from the flank. This portrayal might be uncommon because a wild yak is inherently less vulnerable when approached from the side, as it could spin around and charge a hunter more easily than if he came at it from the rear.

Fig. 36. Mounted archer killing a wild yak from the rear, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

In this standard depiction the wild yak is shown with a male sexual organ. While this is not a common motif, it appears that many (if not all) wild yaks in hunting scenes are male. The large bulk, long belly fringe and large humps of the animals suggest this gender identification, as does the heroic spectacle of wild yak hunting itself. The need to vaunt personal and social achievement in this genre of rock art favors bull hunting over the slaying of wild yak females (despite their meat being better).

Fig 37. Horseman chasing a wild yak, eastern Changthang. Probably Early Historic period.

The bow of the pursuing hunter is just recognizable. This hunting scene occurs among many other pictographs but it appears to be an integral composition. The wild yak is attempting to flee but it may have been already hit by arrows in this painting, in a stereotypic display of death and the victory of the hunter.*

For this composition, also see Suolang Wangdui 1994, p. 145 (fig. 183); Bellezza 2002b, p. 362 (fig. 4).

Solitary horseman in association with wild yaks and other animals

In this subsection a variety of rock art compositions featuring horseman and wild yaks are illustrated. The common thematic denominator is that the animals are not depicted being graphically killed, suggesting that another set of motivations and functions may be behind the creation of this art. Some riders in these compositions are equipped with the bow and arrow while others are not.

Fig. 38. A mounted archer and two wild yaks, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

While there is some question whether one or both wild yaks belong to this composition, it has little effect on the import of the scene. The horseman is in front of the wild yaks and not shooting directly at them. Armed with a bow and arrow, however, it is clear that he is a hunter. In this type of composition, the wild yak is depicted in all its glory very much alive and unmolested. Perhaps this genre of art is celebratory in nature, not only of the hunt itself, but of the wild yak as an animal with myriad desirable qualities and functions.

Fig. 39. Mounted archer and giant wild yak, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

What appears to be the bow of the horseman is visible, but it is not clear if he is shooting at the wild yak. This composition may be another example of a hunter portrayed with his prey that also serves as a paean to the living animal. Below the wild yak are indistinguishable minor carvings.*

For this composition, also see Bellezza 2001, pp. 221, 363 (fig. 10.88).

Fig. 40. Horseman, sun, triangular subject, and wild yak, western Changthang. Iron Age.

The horseman does not seem to wield a bow and arrow. The sun is of course the source of warmth and life more universally. The carved example in this composition has nine rays, a number that has acquired much mythic, religious and cosmological significance in Tibet. The triangular form has not been identified. The wild yak seems to go about its business undisturbed. The horseman may or may not be a hunter, but this is not a hunting scene per se. Although graphic hunting scenes are commonplace at the site, this composition seems to extol the environment and way of life of the wild yak hunters who frequented it.

Fig. 41. Mounted archer, sun, wild yak, and two other animals, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

In this rock art the archer appears to be aiming directly at the wild yak. It looks as though one arrow is also flying through the sky and one or two others have already hit the animal. There is a sun, wild caprid and another animal in the composition as well. Again the sun has nine rays, suggesting that the sacred aura surrounding this number in Tibet has very long antecedents. While hunter and prey make up a large part of the composition, other narrative or ritual aspects of life in Upper Tibet are also invoked.

Fig. 42. Mounted archer pursuing wild yak with wild caprid, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

This is a typical Upper Tibetan wild yak hunting composition with the addition of what appears to be a wild caprid to the scene. It is fairly uncommon to find other species of wild herbivores in wild yak hunting rock scenes.

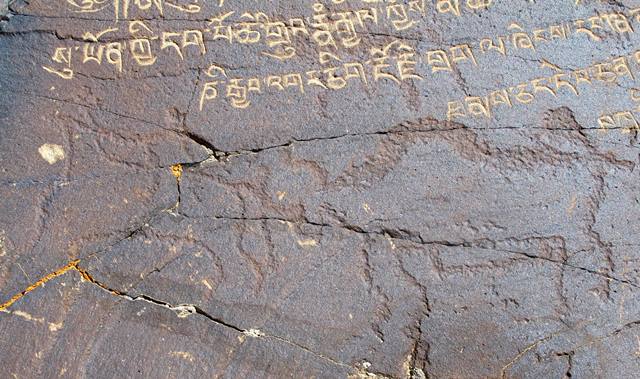

Fig. 43. Mounted archer and wild yak facing in opposite directions, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

In this composition the hunter is clearly not in the act of slaying the wild yak. Both appear to be co-existing in their respective realms. One might read this as expressing great respect for the wild yak, the most important quarry of hunters, but also an animal with many other purposes in the culture of Upper Tibet (see Part 1). The belly of the wild yak has two volutes and a line bisects its body. The wild yak’s back, tail and head are silhouetted. This animal is depicted in an Upper Tibetan version of the Eurasian animal style. Most Eurasian animal style art in the region, however, only portrays animals. The head of the hunter’s mount forms a circle.*

For this composition, also see Bellezza 2001, pp. 221, 363 (fig. 10.89).

Fig. 44. Horseman in front of wild yak, far western Tibet. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

It is not clear if the rider is holding the reins of his mount or is armed with a bow. The two figures are nearly making contact in a symbiotic relationship of some kind. The horseman may be leading the wild yak or in concert with it in some other fashion. If indeed the horseman actually leads the wild yak, this could be a scene of taming or early domestication. Nevertheless, as there is only a single yak represented, other more symbolic shades of meaning may have been intended. This kind of theme is not commonly represented in the rock art of Upper Tibet, which also suggests that it does not portray the pedestrian activities of herdsmen.

Fig. 45. Wild yak, another wild ungulate and horseman, Western Changthang. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Here again we see a wild yak and horseman in what appears to be nonthreatening interaction. The horseman does not seem to be brandishing weapons.

Fig. 46. Probable wild yak, smaller animal and mounted archer, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

The erect wedge-shaped tail identifies the upper animal as a wild yak. Although the archer is wielding a bow, he faces away from the two animals. These animals are obvious prey for hunters but in this composition they are left unharried.

Fig. 47. Horse rider, unidentified animal, two wild yaks, two circles, and other minor carvings, Central Changthang. Iron Age.

The theme of this fairly complex composition is unclear. The horseman points ahead as if leading the other animals. Possibly it depicts the taming or domestication process, the habituation of wild animals with human beings. If that is the case, perhaps the circles represent pens. Yet, it is also possible that this is a mythic or narrative scene with an entirely different import. It is unlikely, however, that the composition depicts stock rearing or other animal husbandry functions associated with pastoralism. The theme of pastoralism is virtually unknown in the early rock art of the Tibetan Plateau.*

However, Suolang Wangdui (1994: 125 [fig. 142]) interprets this composition as depicting a herdsman leading a yak and other animals.

Fig. 48. Horseman followed by two wild yaks, far western Tibet. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

This composition portrays a horseman with two wild yaks behind him. Possible interpretations for the scene are the same as suggested for fig. 47. The horseman appears to hold the reins of his mount.

Fig. 49. Horseman between wild yak and stag, far western Tibet. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

It is not clear if the rider is a hunter or not. There are historical indications that deer were once tamed in Upper Tibet, but it is not known if this cultural intelligence has any bearing on the theme of this rock art. Narrative sequences related to the mythic or legendary could possibly be at play here.

Next Month: The group hunting of wild yaks!