August 2012

John Vincent Bellezza

This month’s newsletter is dedicated to tigers, that fearsome carnivore of eastern Eurasia. These creatures are part of the cultural and artistic heritage of many peoples in the region. Similarly, there is much fascination with tigers in Tibet, a symbol of divine power, martial prowess and magical ability. We shall examine the tiger of Tibet through Tibetan texts, the natural sciences and Upper Tibetan rock art.

Long live the tiger!

A brief introduction to the tiger in Tibetan culture

For a very long time tigers have been the stuff of legends in Tibet. To this day robes trimmed in the skins of the tiger and leopard are considered a desirable embellishment and status symbol. It is written in Bon and Buddhist historical texts that an ancient insignia of superior distinction (rtsigs) was a robe (thul-pa or slag-pa) trimmed in the fur of a tiger (alternatively leopard or clouded leopard skin). Such robes were awarded to valiant warriors and saints alike. According to Bon historical texts such as G.yung drung bon gyi rgyud bum, this tradition endured until the reign of King Trisong Deutsen (Khri-srong lde’u-btsan, 755–797 CE). This text also notes that circa the 5th century CE, Tritsennam (Khri-btsan-nam, Tibet’s 25th king,) and Thothori Nyentsen (Tho-tho-ri gnyan-btsan, the 27th king) presented bon and gshen priests with tiger skin trim and headgear as a badge of courage (che-rtags) for their aid in defeating foreign enemies.

Anyone familiar with the Ling Gesar epic or the cult of mountain deities would have heard of the tiger-skin quiver and leopard-skin bow case. These are stock-in-trade accoutrements of the ancient warrior in Tibet. These men-at-arms carried the appellation ‘tiger-dress hero’ (dpa’-bo stag-chas), and their costumes and weapons were referred to as the ‘equipment of the tiger’ (stag-chas). The greatest exploits of the warrior were epitomized in the phrase: ‘conquering male tigers in their prime’ (skyes-pa stag-’gugs). Like the tiger itself, these military heroes of yore, were given the epithet ‘wild one’ or ‘brave one’ (rgod-po). The proud and imperious swagger of the warrior known as the ‘tiger’s gait’ (stag-’gros) was adopted in wrathful ritual procedures. Tiger Gait is also said to be the secret name of the Bon tutelary deity connected to an ancient sage known as Shebu Rakhuk (Shad-bu ra-khug) and his consort Odenma (’Od-ldan-ma). This couple is recorded as residing in Yakpa (G.yag-pa), a region in the eastern Changthang.

Given this costumery tradition, it is not surprising that a wide spectrum of indigenous Tibetan deities is clad in tiger skins. Mountain gods, sprites of the earth, personal protective divinities, spirit allies in battle, and many other classes of deities are dressed, in whole or in part, in tiger fur. The use of tiger skins as vestments and other attributes extends to Buddhist deities as well, especially the protectors known generically as chos-skyong. Some of these Buddhist protectors have tigers and other wild felines in their entourages. Certain Tibetan deities are mounted on tigers such as the god of blacksmiths, Damchen Garwa Nakpo (Dam-can mgar-ba nag-po). As in Tibet, in ancient India, the tiger was held in high esteem and crept into many myths, legends and customs.

In the realm of healing there are helping spirits of Upper Tibetan mediums in the form of the tiger (and other wild animals). While possessed the spirits mediums behave like tigers growling and leaping around. It is believed that divine creatures like the tiger assist in healing a wide range of maladies afflicting humans and livestock. The divine tiger is also called upon by mediums to attract good luck to people who have suffered much misfortune.

Tiger skin is used in a variety of Tibetan rituals. For example, in a ceremony to summon good fortune (g.yang-’gugs), tiger and leopard skins are used to ornament the backs of specially selected sheep. In a bon funerary rite in which horses are used to transport the soul of the deceased to the other world, a yak, tiger and lion are drawn on the back of the saddle. According to the celebrated 11th century CE historical text Bka’ chems ka khol ma, when Tibet’s first king Nyatri Tsenpo (Gnya’-khri btsan-po) came down to Yarlung, his palace was made of tiger, leopard, wild yak, and deer skins. Whether it is dogs and horses with variegated coloring described as having the ‘stripes of the tiger’ or gods who act as a ‘leaping tiger’, this big cat is deeply imbedded in the art and literature of Tibet.

Much is said in Yungdrung Bon texts about the tiger in the religious and political craft of prehistoric and early historic Tibet. These texts were mostly composed between the 11th and 15th century CE.* By virtue of being written many centuries after the fact, these references to the cultural value of tigers assumed a legendary coloring and were infiltrated with concepts of Buddhist inspiration. That said, the quasi-historical literature of Yungdrung Bon has indeed preserved ancient Tibet customs and traditions, even if some of the personalities mentioned are composite creations or token in character.

Famous Upper Tibetan bon saints such as Drenpa Namkha (Dran-pa nam-mkha’, 8th century CE) and Shebu Rakhug (protohistoric period) are claimed to have been able to manifest as tigers and other wild animals, in order to carry out ritual work and esoteric practices. The early bon saints are also supposed to have kept ferocious wild animals like tigers in the same way ordinary people herd goats and sheep. Wild ungulates and carnivores are said to have circumambulated these adepts, a sign of their tremendous sanctity and ability. The cosmogonic text Dbu nag mi’u ’dra chags, composed in its present form in the 13th century CE but containing older lore, details how a divine couple manifested as tigers and other animals, so as to beget the kings of India, Tajik, Khotan, Nepal, and a Central Asian country called Throm (Phrom). The warrior spirits known as dgra-lha, which served as clan totems, often appear in the guise of tigers. There are also various clan emblems with the attributes of the tiger. Although these traditions are largely mythic in nature, they do help to illustrate how well ingrained the tiger is in Tibetan culture.

In Upper Tibet, there are many place names that carry the appellation ‘tiger’. One of the most famous is Tiger God Fortress (Stag-lha mkhar). Located in Purang in southwestern Tibet, this fortress supposedly dates to the time of the Zhang Zhung kingdom. The hill on which it stands is thought to resemble a sleeping tiger. Another famous location in uppermost Tibet is Takrong (Stag-rong), a gorge with geysers that is still closely associated with ancient bon. There are also a number of places in the region that are called Tiger Valley (Stag-lung). As many readers may already know, a Tiger Valley in Central Tibet has lent its name to a subsect of Buddhism (Stag-lung bka’-brgyud).

* There are however even older sources. Among the oldest Tibetan texts that mention tiger-skin dress and ritual instruments made from tiger hide are those from the recently discovered Gathang Bumpa collection. These texts date to circa 850–1000 CE. For references, see:

2010. “gShen-rab Myi-bo: His life and times according to Tibet’s earliest literary sources” in Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, no. 19, pp. 31–118. Paris: CNRS.

http://www.himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_19_03.pdf.

Forthcoming. Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet: Archaic Concepts and Practices in a Thousand-Year-Old Illuminated Funerary Manuscript and Old Tibetan Funerary Documents of Gathang Bumpa and Dunhuang. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Note: For an elaboration of the tiger in the culture of Tibet, see my other books and papers too.

Ancient tigers in Upper Tibet

In light of the evidence, I shall argue for tigers as having been indigenous to Upper Tibet. I must stress, however, that I am an archaeologist and cultural historian, not a wildlife specialist or paleozoologist. The subject of the territorial range of the tiger in antiquity as possibly extending into Upper Tibet requires study by experts who can furnish us with scientific confirmation. Of critical importance is a field mission to the region to locate the skeletal remains of long-dead tigers. The evidence presented here for your consideration, while not conclusive, is certainly convincing enough to warrant further inquiry into the subject.

The tiger that still survives in southeastern Tibet is the Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris). On biogeographical grounds, I shall put forward that any tigers once found in western Tibet were the Caspian variety (Panthera tigris virgata), a subspecies very closely related to the Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris altaica). Both of these subspecies are believed to be descended from the same ancestor, as recent genomic research has shown. The Caspian tiger had golden or reddish pelage with stripes, ranging from light brown to dark brown. It was once found south of the Caspian Sea and to the east across Central Asia, all the way to the Tarim Basin and Lop Nur. Thus, the Caspian tiger roamed in areas adjacent to the Tibetan Plateau.

It is not agreed upon by wildlife experts when the last Caspian tigers died out in the wild (unfortunately, there are none left in zoos either), but it may have been as late as the mid-20th century. Even today there are occasional sightings of tigers reported in remote parts of eastern Turkey but none of these have been confirmed. The habitat of the Caspian tigers was steppe forests and riparian corridors, places where there was sufficient vegetative cover for the animals to hide as well as containing ample supplies of prey such as deer, gazelles and wild pigs. Their habitat being somewhat restricted made the Caspian tiger particularly vulnerable to hunting and human encroachment.

If the Caspian tiger was once native to Upper Tibet, its habitat was probably restricted to the valley systems of western Tibet. In Gar, Purang, Guge, and Ruthok there are extensive valley networks between 3200 m and 4500 m elevation, which still support stands of tamarisk, dwarf willow, buckthorn and other scrub species. Before the full extent of late Holocene environmental degradation, these valleys must have been lusher and more ecologically diverse. Wild asses, gazelles (at higher elevations) and hares still thrive in these riverine biomes. Deer may also have been plentiful at one time, as indicated by the oral and literary traditions, chance excavation of deer skeletons in the region, old deer horns kept as prized heirlooms, and the rock art record. Furthermore, wild yaks once thrived in western Tibet. They are now almost completely restricted to the northern Changthang.

Tigers have been spotted in the Indian Himalaya in rocky locations at elevations up to 3500 m, especially when the species was more plentiful in British Raj times. Recently, the Bhutan Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, in collaboration with a foreigner team, observed tigers living at up to 4100 m (see “Lost tiger population discovered in Bhutan mountains” in BBC Earth News, September 20, 2010: http://news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_8998000/8998042.stm). That the male was scent-marking is thought to indicate that he and his mate are actually living at that altitude. The exploitation of high-elevation habitats by tigers demonstrates that it would have been physiologically possible for tigers to have once thrived in rarefied western Tibet (and Ladakh).

Cultural data supports the view that the tiger was once native to Upper Tibet. The textual traditions that speak of tiger skin costumes and ritual objects are found in tandem with those fabricated from other animals indigenous to Upper Tibet (e.g., vulture, brown bear, wolf, lynx, wild yak, etc.). There is no indication in these sources that the tiger was singled out as an exotic species. The tiger is an integral part of formative iconographic, martial, ritual, and social traditions, which are presented as being of Tibetan origins. The endemic cultural mantle enjoyed by the tiger in Tibetan literature supports the possible former existence of tigers in western Tibet.

As we shall see in the next section, tiger rock art in western Tibet depicts the species in naturalistic contexts as a hunter of wild ungulates. This art seems to chronicle a natural phenomenon that inhabitants knew firsthand. That almost none of the tiger rock art is located in the Changthang, adds to this sense of the carvings being inspired by a geographic association with the species. This is surely the case with ibex rock art, which while very plentiful in Ladakh, is not found in western Tibet, reflecting the natural distribution of this wild ungulate.

As a point for further deliberation, I shall suggest that if tigers were indeed found in western Tibet, they may have gone extinct by the end of the Iron Age or not much later than that. Sedentary settlement appears to have widely expanded in the Iron Age with the development of citadel agricultural centers. With the establishment of this type of human occupation the competition for natural resources intensified, leading possibly to the extirpation of the tiger in western Tibet. This at least is my current theory. Now I leave it up to those better qualified in the science of the tiger to assess it.

Tigers in the rock art of Upper Tibet

All dates given below are estimates based on a stylistic analysis, an examination of the physical traits of carvings and paintings, the nature of rock art in general at each site, and cross-cultural comparisons. These dates should be taken as suggestive and not prescriptive.

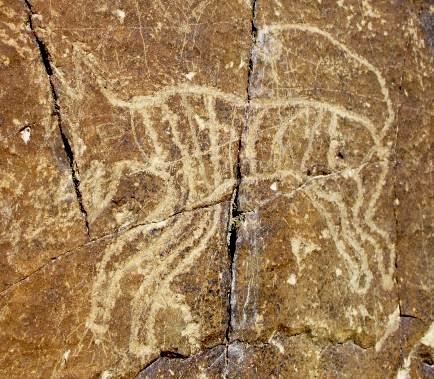

Fig. 1. With its pointed ears, stripes and long curling tail, the identification of this animal as a tiger seems unmistakable, Iron Age (700–100 BCE) or protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE).

This rock art tiger is located on a cliff overlooking a relatively lush valley with plenty of water. This is one of two tigers on a rock panel first published in Suolang Wangdui’s Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings, 1994 (p. 71, fig. 38). On this panel, a deer and stick animal are also depicted between the two striped carnivores. In Suolang Wangdui’s book, two tigers among yaks and deer (p. 53, fig. 11), a tiger amid many other animals and two shaman-like figures with ray-like protuberances on their heads (p. 54, fig. 12), and a single tiger with gaping mouth (p. 56, fig. 17), all from the Lu-ring sna-kha site, are illustrated. This highly valuable rock art chronicles the natural and cultural history of the tiger. Sadly, all of these tiger petroglyphs were recently destroyed by a road crew (see January 2012 newsletter for more details).

Fig. 2. The other tiger carving on the same panel as figure 1, protohistoric period. Its pointed ears, long, curling tail, gaping jaws, stripes and long tail need no comment. The two tigers of the panel are gracile in form. Perhaps the tigers of western Tibet were considerably smaller than average-sized Caspian tigers, which lived in more conducive physical environments. It is worth proposing that these ‘Tibetan’ tigers may have belonged to a genetically distinctive subspecies, but this is pure speculation.

Fig. 3. Tiger (upper left hand corner) chasing wild ungulate, protohistoric period.

This action-packed composition was defaced by the carving of a mani mantra over it by a zealous Buddhist. The rock art record of Upper Tibet is full of this type of activity, which amounts to graphic suppression of the earlier cultural history of the region carried out for religious or ideological reasons. This tiger and its prey were engraved in a style close to that of the steppes and the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Common stylistic motifs include standing on the tips of the feet, legs with sharp, angular flexes, a few stripes, and wide, gaping jaws. The tail curled over the back of the feline terminating in a tight spiral, however, is an Upper Tibetan trait. In a forthcoming paper, a colleague and I explore these steppic connections in some detail.

Thousands of petroglyphs have been documented In the Helan Mountains on the border of Inner Mongolia. In an online article on the Bradshaw Foundation website entitled “The Tiger in Chinese Rock Art” (http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/china_tiger/index.php), twelve tigers from the Helan mountains are shown. Unfortunately, this article insinuates that it was the ancient Han who carved these tigers, when this is certainly not the case. The tiger rock art of the Helan Mountains is in fact highly diverse, reflecting the changing ethnic composition of the region for around two millennia (roughly 1500 BCE to 700 CE). Much of the stylistic inspiration for this rock art came from the steppes. While no specific ethnic group can be connected to it beyond a shadow of a doubt, first Proto-Mongolic peoples followed by the Hsiung-nu and Hsien-pei may well have been some of those involved in its creation. The great bend in the Yellow River in the Ordos is located in the vicinity. Some of the tigers of the Helan Mountains, with their volutes and stripes and general forms, are comparable to the so-called Ordos bronze plaques. Fainter artistic influences can be traced to the Scytho-Siberian tribes.

Fig. 4. A tiger chasing what appears to be a deer with forked antlers, Iron Age or early protohistoric period. The deer is looking behind it as the tiger is about to pounce. Again, we see the tiger as part of the region’s predator-prey cycle, seemingly strong evidence for its existence in western Tibet. For this image, also see my book ‘Zhang Zhung’ (p. 169, fig. 296).

Fig. 5. A tiger (Iron Age) with tail curved over its body bordering a chorten petroglyph. Note the different degree of re-patination in the two carvings. There are also two ancient wild ungulates in close proximity. For these animals, see my book Antiquities of Northern Tibet (p. 350, fig. 10.62)

Fig. 6. A tiger, which is part of a complex mytho-ritual scene published previously; see Zhang Zhung (p. 175, fig. 310) and “Images of Lost Civilization: The Ancient Rock Art of Upper Tibet” in Asian Art Online Journal. http://www.asianart.com/articles/rockart/index.html. This composition appears to date to the protohistoric period. It is gracefully rendered, complete with all the prominent features of Upper Tibetan tiger rock art. Next to the tiger in the composition is a wild yak rendered in the same style. Both of these animals may signify divine protectors.

Fig. 7. A tiger amid many other animal carvings, late Bronze Age or Iron Age. In addition to other typical anatomical features, the claws of the tiger are discernible.

Fig. 8. A tiger attacking wild yaks, late Bronze Age or Iron Age. Interestingly, this tiger has a checkered design, as does the specimen in figure 7. They are both situated on the same boulder. This yak hunting scene signals paleoecological conditions that existed in western Tibet. Wild yaks once grazed throughout the region. The swastika may possibly indicate that this panel had a mytho-ritualistic function; perhaps something related to the celebration of martial or venatic aspects of the makers’ culture.

Fig. 9. Two tigers attacking wild yaks, late Bronze Age or Iron Age. This is the first time that such compositions have been published. They seem to show that wild yaks were a primary food source for the highland tiger.

Fig. 10. A red ochre pictograph, eastern Changthang, early historic period or vestigial period (1000–1250 CE). This is the only ostensibly historic era tiger to have been documented in Tibetan rock art and the only one found on the Changthang. Given the epigraphy and other rock art at this locale, this pictograph is likely to have had religious value for non-Buddhist cults we can loosely refer to as bonpo. In style, this red ochre tiger is not unlike some tiger copper alloy talismans (thog-lcags).

Fig. 11. A copper alloy tiger talisman designed to be hung from the body, early historic period or vestigial period. Tiger thokchas are not particularly common. This specimen has a rather cartoonish character. Private collection, photograph by author.

Hopefully, these images will stimulate further debate as to the true geographical extent of Caspian tigers in ancient times.

A final word in this newsletter on the cultural orientation of tiger rock art in Upper Tibet: Although these carvings and paintings are chronologically and stylistically diverse, they belong to a genre of rock art that is uniquely Upper Tibetan. While there are certain stylistic affinities with the rock art of northeastern Tibet, Ladakh and the steppes, the Upper Tibetan variants were probably created exclusively by people residing in that region. The earliest tier of tiger art appears to have been produced in a period when Upper Tibet had manifold cultural and possibly ethnical links with surrounding Eurasian peoples, however, it developed in ways that are truly indigenous. Tibetans can be proud of the beauty and vitality of this art, and what it says about their past long before the rise of Lamaist religion.