April 2017

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung as we journey to uncover the secrets of ancient Tibet! Many of the places and things highlighted in these newsletters have been forgotten for 1000 years or more, this month’s issue being no exception. Regular readers will remember the series on wild yak hunting that appeared last year. This month and in the next two newsletters just wild yaks in the rock art of ancient Upper Tibet are featured, complementing the earlier work on wild yak hunting.

Cutting Horns and Thundering Hooves: Wild yak portrayals in the rock art of Upper Tibet – Part 1

Introductory essay

Overview of wild yak rock art

This article (in three monthly parts) examines a wide variety of wild yaks in the rock art of Upper Tibet.* It features pictographs (rock paintings) and petroglyphs (rock carvings) portraying wild yaks in isolation. The vast upland plains and valleys of Upper Tibet hold the greatest concentration of wild yak rock art on the Tibetan Plateau. Although the extreme western fringe of the Tibetan Plateau (Baltistan, Ladakh and Spiti) boasts large quantities of rock art, wild yaks make up a much smaller percentage of the total number of rock carvings and paintings in that geographic zone.

Upper Tibet consists of the overlapping Far Western (Stod) and Changthang (Byang-thang) regions.

Rock art consisting of solitary wild yaks in what appear to be naturalistic settings comprise the bulk of this work. Other rock art compositions illustrated depict two or more wild yaks or wild yaks in conjunction with other species of wild herbivores. More than 230 photographs are presented, a broad cross-section, stylistically, technically and chronologically, of the approximately 1500 wild yak sans anthropomorphic figures found in the rock art of Upper Tibet.*

I estimate that there are no less than 10,000 individual pictographs and petroglyphs in the rock art of Upper Tibet. Roughly 75% of this rock art is made up of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures. An accurate tally has not yet been compiled but there are more than 6000 pictographs and petroglyphs representing animals. Of this zoomorphic rock art, approximately 70% is composed of wild yaks, making up perhaps 40% of the total number of rock carvings and paintings in Upper Tibet. Possibly two-thirds of all wild yaks occur in hunting compositions and the remaining third in non-hunting compositions. It is difficult to discern the precise number of hunting and non-hunting compositions because of uncertainties in the identification of some human figures. Wild yaks are found at approximately 80% of the more than eighty rock art sites documented in Upper Tibet (seventy-five of which I have personally surveyed).

This article complements an earlier one in Flight of the Khyung entitled “Bravery, Propitiation and Accomplishment: Wild yak hunting in the rock art of Upper Tibet” (July, August and September 2016). That work furnishes a comprehensive cultural and historical review of the wild yak (’brong), focusing on the relationship between wild yaks and hunters, mythic personalities, ritualists, and other anthropomorphic figures, including the depiction of cultural, economic and technological elements in rock art compositions. Readers are encouraged to consult the earlier article for information and lore about the wild yak, the largest native mammal of the Tibetan Plateau.

Esthetic and technical features of wild yak rock art

The tradition of producing facsimiles or simulacra of wild animals developed early in the rock art-making era of Upper Tibet and prevailed until early historic times. The high frequency of wild yaks in the rock art of the region (there are roughly 4000) and the long period of production (at least 2000 years) contributed to significant variability in conception, form, execution, and pictorial context. The repertoire of individual motifs, their relationship to one another to create styles and the arrangement of individual subjects to comprise scenes are major elements contributing to the aesthetic constitution of wild yak rock art. The personal inclinations of makers, the cultural and social conditions influencing artists, techniques of production, and artistic proficiency also shaped the tradition of wild yak depiction. The pre-Buddhist canon of wild yak figuration not only encompasses rock art but also copper alloy amulets known as thokcha (thog-lcags) and early stone and metal sculptures. Traces of this artistic canon are still discernable in Buddhist and Bon paintings and sculptures and in contemporary artisanal productions. These longstanding continuities in wild yak portrayal have significantly enriched Tibetan art over the course of civilization on the Plateau.

In Upper Tibet, wild yaks were either painted or carved on stone surfaces as outlined (open) or silhouetted (solid) figures. This art appears in a welter of styles and kinds of compositions relying on multiple techniques of production. The degree of realism or abstraction varies significantly, as does the parts of the animal emphasized, given over to special treatment or neglected. Figures range from crude and cursory to adroit and highly detailed, revealing the level of care and skill that went into creating wild yak rock art.

Pictographs were made using red and yellow ochres (oxides of iron) of various hues and black pigments (oxides of manganese or charcoal) lightly or more copiously applied with the fingers or with tools such as bones, antlers, quills, brushes, etc. (identification of these tools is still hypothetical). Pigments were administered on stone surfaces by dabbing, scoring and slathering, etc., producing different tones and effects. Almost without exception, pictographs of wild yaks occur in parietal structures (caves, fissures and under ledges). In contrast, petroglyphs of wild yaks are usually encountered on exposed boulders and open rock faces, receiving the brunt of the elements. Petroglyphs were made by etching, pecking, gouging, and chiseling stone surfaces, wielding a variety of sharp implements that may have included sharp stones (burins, celts, etc.) and edged bronze and iron articles (chisels, knives, etc.). The manner of removal of bits of stone surfaces and the tools used to accomplish this had much impact on the tones and effects of rock carvings. The appearance of wild yak rock art was also affected by the physical qualities of the stone worked, with finer textured varieties and more uniform surfaces apt to yield petroglyphs with more salient forms.

Despite many technical and aesthetic variations in presentation, wild yak rock art in Upper Tibet is identifiable through well-defined anatomical traits rendered by carvers and painters. Artists often strove to create accurate likenesses of wild yaks, faithfully reproducing their most recognizable physical features such as curved horns, massive bodies and bushy tails. The most prominent anatomical motifs of wild yak rock art include triangular, rectangular and rounded heads, large circular or semi-circular horns, oblong or rectangular bodies, conspicuous rounded humps and S-shaped backs, ball-shaped or wedge-shaped tails, a fringe of belly hair, and either two or four legs. These anatomical motifs occur in any manner of forms and combinations, depending on the creative output of individual artists. In some examples, the size of tails, horns, humps, and belly fringes is exaggerated, calling attention to these outstanding traits of wild yaks. There are however exceptions to the tradition of conventionalized wild yak depiction in Upper Tibet, obscuring the identification of some specimens. Non-canonical examples are ambiguous in nature, calling into question whether a subject is a wild yak, another species of wild herbivore, or something entirely different.

The existence of a canon or system of wild yak rock figuration in Upper Tibet reflects natural constraints in the manner of the depiction of the species. Replication of the same motifs, styles and scenes for upwards of two millennia, however, also reflects a significant degree of cultural continuity in the region. This art historical evidence when considered with other types of archaeological evidence,* strongly suggests that Upper Tibet enjoyed an unbroken chain of ideological and symbolic transmission from the Late Bronze Age until the Historic Epoch, informing the culture and religion of the region more broadly. Longstanding continuities in the population make-up of the region are also suggested by the art historical and archaeological evidence.

For example, on continuities in bronze metallurgy, see article in March 2016 Flight of the Khyung; on archaeological and genetic continuities more generally, see book review in March 2017 Flight of the Khyung. Also, see final article in next month’s (May 2017) Flight of the Khyung.

Functions and meaning of wild yak rock art

Wild yaks make up a majority of zoomorphic art in ancient Upper Tibet, reflecting the cultural and economic importance of this animal to the Tibetan Plateau. Wild yak rock art in its sundry forms is an archaeological resource of considerable value for understanding the cultural complexion of the region in ancient times.* The wide distribution, high incidence and compositional versatility of wild yak petroglyphs and pictographs contributed much to the cultural output of Upper Tibet in the pre-Buddhist or prehistoric epoch.

Together with ancient monuments (residential, burial and ceremonial) and artifacts (metallic, stone, ceramic, etc.) discovered in Upper Tibet, rock art serves as a primary instrument for evaluating the way of life followed in the region in the prehistoric epoch. The material assemblage of rock art, monuments, artifacts, and natural products, as the expression or materialization of the people who created and used them, constitutes what is known as an ‘archaeological culture’. Especially when viewed in its entirety, this physical evidence reveals intellectual, artistic, technological, economic, and social patterns of its producers and users. Nevertheless, there are many cultural realities related to everyday affairs and the inner or conceptual life not readily discernable in the material record. Moreover, tangible evidence may say little about ethnic and linguistic affiliations, for physical forms can be transferred or recreated beyond such bounds. Thus, an archaeological culture cannot necessarily be equated with an actual culture, a self-identifying group of people sharing a language, genetic wellspring, customs, traditions, beliefs, social structures, and subsistence strategies, etc. The material assemblage of Upper Tibet is distinctive and in some respects unique, indicating that it corresponds to an actual culture, which differed in varying degrees from cultural formations in adjoining regions.

Although wild yak rock art confirms the importance of this herbivore to the people of ancient Upper Tibet, the study of its cultural value is not a fixed feature, as methodological and theoretical approaches to examination and analysis change over time. Intellectual movements, political developments and technical innovations notwithstanding, this provisionality stems from the great time gap separating makers of wild yak rock art from those observing it today. This distance complicates not only an investigation into the purpose and meaning of rock art but other areas of archaeological inquiry as well. Much has been written on this topic, but it will suffice here to say that the theories and methodologies put forth to explain what rock art compositions might have signified to their makers and users have not been widely agreed upon. In my opinion, the matter of why a piece of rock art might have been made is best approached in an inclusive fashion, marshaling findings that are interdisciplinary in scope and producing assessments that are not overly prescriptive but also not too broad as to be effectively meaningless. Striking a balance between these two extremes is not an easy prospect, as the means for scientific verification of most interpretations remains elusive.

We cannot be certain which more recent Tibetan religious and cultural concepts and practices are reflected in prehistoric wild yak rock art, for there are no written records or other indisputable indications divulging this information. As I have noted in earlier works, the portrayal of solitary wild yaks or wild yaks in pairs and groups may possibly have fulfilled a variety of functions and could have been perceived of in different ways by makers and users. The rock art-making tradition in Upper Tibet endured for around 2000 years, spanning both the prehistoric and historic epochs. This long stretch of time is characterized by fundamental technological, cultural, economic, political, and environmental changes. Therefore, there is no reason to assume that the wild yak, a ubiquitous presence in the lives of Tibetans, past and present, always meant the same thing to all those who carved or painted its likeness on stone. Even today, the wild yak has a multifaceted character, serving as a religious icon, local and national identity marker, hunter’s trophy, and social status symbol, as well as being an economically useful animal producing meat, hides, horns and other key commodities.

Seen as shifting cultural representations over time, the depiction of a lone wild yak or group of wild yaks in Upper Tibetan rock art assumes a multivalent identity. It is not just one thing or the other, but many potential significates. Although these cannot be determined with any surety, I will enumerate a few area areas of potential meaning and function for wild yak rock art. This serves to underline the importance of this art to its makers and users, and provides a point of departure for future inquiry.

Although there are perhaps 4000 wild yak subjects in Upper Tibetan rock art, this is a relatively small number given the size of the region and the amount of time involved. Clearly, carving or painting wild yaks was not the province of everyone. It was an activity in which a small segment of the population over a long period participated directly. The special or specialized nature of rock art making is also implied by the dignity and stature with which wild yak rock art is imbued. This art is frequently comprised of carefully rendered figures appearing in diverse compositional genres.

At its most simple, portrayals of wild yaks in Upper Tibetan rock art may have been made as an indulgence, a recreational pursuit to entertain and pass time. However, this rather inconsequential motivation cannot account for all or even most of the several thousand wild yak carvings and paintings in the region. Many of these are too elaborate, conventionalized and strategically placed in compositions to have been created merely as a diversion. Rather, regular modes of conception and activity of some consequence are involved. Wild yak rock art, when accompanied by hunters, demonstrates that the killing of this animal was a key social custom and prime economic activity and probably an object of ceremonialism and focus of ritual practice. Wild yak rock art, even when hunters are absent, may have acted as a magic instrument to ensure the success of hunters, to attract game, to convey thanksgiving, or to augment the fecundity of the stock of animals. Whether wild yaks were carved and painted before or after the hunt, the propitiation and veneration of ancestral, territorial and protective deities could well have played a part.

Wild yak rock art featuring chariots, mascoids (emblematic anthropomorphic figures), mythic figures, other iconic animals, etc. augments the social, cultural and religious significance of this bovid. Some such scenes include anthropomorphic figures in extraordinary garb and aspect and sacred symbols (e.g., crescent moon, swastika, sun). Surely, packages of beliefs, customs and traditions associated with the cultural, economic and political environment of ancient Upper Tibet are reflected in complex wild yak rock art. The contemporary cultural scene is also illustrative: Upper Tibetans live in a highly marginal physical environment and are deeply steeped in religion and myth in which wild yaks still play a part.

Many of the compositions in this article feature lone wild yaks, also enhancing the stature of this bovid in ancient Upper Tibet. This rock art shows that the wild yak was worthy of depiction for its own sake, in scenes potentially with both a prosaic and an extraordinary purview. The heavy bodies, prominent humps, big, bushy tails and hairy belly fringes of most rock art examples strongly suggest that these are renditions of bull yaks. A wild yak bull is the lynchpin of the herd, a largely self-contained and proud beast with awe-inspiring physical and behavioral qualities. This usually solitary creature keeps its distance from other wild yaks except during the mating season. It is the strongest, biggest and most fearless of Tibetan animals. A wild yak bull is large and powerful enough to defend itself against wolves and other predators. Their horns are deadly weapons that can cut a foe in two or fling a horse in the air, and they can easily trample enemies to death. As a paragon of bravery and prowess, wild yak bulls possess qualities esteemed by the warrior, the weapon-wielding figures of Upper Tibet rock art and the Tibetan literary and folk traditions. We can conclude, therefore, that some portraits of solitary wild yak bulls, if not explicitly made in celebration of martial qualities, were produced in tacit recognition of them.

Wild yak portrayals in the rock art of Upper Tibet probably conveyed a semantic vocabulary extending beyond the immediate concerns of hunters and warriors. Some may have been conceived of as numinous forms of the animal, which functioned as protective, ancestral or territorial spirits for individuals, clans and tribes. Wild yak deities with genealogical and apotropaic functions still exist in the culture of Upper Tibet. Others may have been primarily fertility or cosmogonic manifestations, as reflected in the later tradition of the ‘divine white yak of existence’ (srid-pa’i lha-g.yag dkar-po). It is also possible that certain wild yak paintings and carvings were produced in conjunction with funerary observances, acting perhaps as psychopomps. These kinds of funerary functions for yaks are attested in Tibetan ritual literature.

Classification of wild yak rock art

Each wild yak carved or painted in Upper Tibet is essentially a unique expression, no two being identical in every detail. The thousands of individualized subjects can potentially be categorized according to their characteristic esthetic traits or style. The precise number of styles of wild yaks in rock art, however, is ambiguous, as an assessment of common artistic and technical elements is open to interpretation. Moreover, a mixing and matching of many major motifs across the artistic and chronological range of wild yak rock art complicates the neat categorization in this style or that. Thus, images of wild yaks in this work are largely grouped as per one or two shared motifs acting as defining criteria, not by an assessment of all motifs in concert or by a single style per se.

In this study, the main signature used to categorize wild yak rock art pertains to the shape of the tail (i.e., ball-shaped, wedge-shaped, barbed, linear). Another distinctive feature, the shape of the horns (i.e., inward curving, circular, double curved, straight), was not in itself used to classify rock art because it does not correlate well with the shape of tails. Other defining motifs include body shape, body ornamentation, belly hair or lack thereof, and the number and type of legs depicted.

In the gallery of images presented below wild yak rock art is divided by prominent motifs into 16 different groups. These groups are not highly discrete categorizations: there are many motifs that occupy an intermediary position to those set out as criteria. Thus, the terminology used to describe motifs is inexact and somewhat arbitrary. For instance, there are tails, painted and carved, whose shape is between that of a ball and a wedge.* Furthermore, some examples of wild yak rock art are obscured and not easily placed in one category or the other. The 16 motif-based groups of wild yak rock art are as follows:

- Ball-shaped tail pointing downward

- Ball-shaped tail raised upward

- Ball-shaped tail and belly fringe

- Wedge-shaped tail pointing downward

- Wedge-shaped tail raised upward

- Wedge-shaped tail pointing downward and belly fringe

- Wedge-shaped tail raised upward and belly fringe

- Barbed tail and belly fringe

- S-shaped or volute body ornamentation

- Segmented body ornamentation

- Linear tail pointing downward

- Linear tail raised upward

- No discernable tail

- Stick figure bodies and appendages

- Idiosyncratic combinations of motifs

- Bi-triangular bodies

Another ambiguity concerns the number of legs depicted in some wild yaks. When two parallel lines are used to render legs in either the front or rear position, it can be difficult to ascertain whether an artist intended this perspective to simulate one leg or a pair of legs. In such cases, the number of legs designated in descriptions of wild yaks below should be regarded as provisional.

Additionally, there are four other groupings in the gallery of images. These include pairs of wild yaks each exhibiting various defining motifs, multiple wild yaks exhibiting various defining motifs, mating wild yaks, and drawings of wild yaks made with a piece of red ochre used like a crayon.

Each of the twenty categories of wild yaks are further classified along chronological lines. The chronological attributions suggested herein are estimates based on a variety of benchmarks relying on informed means of analysis. These chronological attributions have not undergone chronometric verification. Thus, they should be viewed as plausible indicators of age, based on a subjective assessment of the empirical evidence and inferences drawn from a wide range of collateral materials. The criteria used to assess the age of rock art include stylistic and thematic categorization, survey of general characteristics of site contents, historical and ethnographic analysis, cross-cultural comparison, application of associative archaeological data, gauging environmental cues, examination of techniques of production, determination of the sequence of superimpositions, and inspection of the erosion and re-patination of petroglyphs and the browning and ablation of pictographs.

The chronological terms used in this work are as follows:

Prehistoric epoch

Late Bronze Age: circa 1200–700 BCE (differential dating of Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age omitted due to lack of data)

Iron Age: ca. 700–100 BCE

Protohistoric period: ca. 100 BCE to 650 CE

Historic epoch

Early Historic period: ca. 650–1000 CE

Vestigial period: ca. 1000–1300 CE

Later Historic period: ca. 1300–1950 CE

Even when analyzed as stipulated above, wild yak rock art resists easy chronological categorization. The system of classification devised is most useful when applied on a site by site basis or to larger assemblages of compositions sharing sundry traits in common. By comparing the esthetic and physical features of many interrelated compositions in tandem, their respective chronological values stand out more clearly. On the other hand, individual compositions viewed in isolation are more difficult to contextualize and date. This is particularly true of wild yak rock art, as many fundamental motifs and styles appear to have been retained for long periods of time. Examination of the techniques of production and deteriorative qualities of wild yak rock art aid in chronologizing it but only to some extent.

Although only a few examples of wild yak rock art in this article are assigned to the Late Bronze Age, some of those attributed to the Iron Age may actually belong to this more remote period. That is because the criteria required to make the distinction between these two periods have not yet been fully formulated. Likewise, distinguishing wild yak rock art of the Iron Age from that of the Protohistoric period is fraught with ambiguity. For the same reasons, the wild yak rock art of the Protohistoric period and Early Historic period are also not so easily differentiated.

Gallery of wild yak rock art images

Group 1: Wild yaks with ball-shaped tail pointing downward

This group of wild yak rock art is characterized by subjects that have ball-shaped or slightly fanning tails that point downward. There is one pictograph among the various carvings in this group. The wild yaks of this category exhibit a diverse range of other motifs, styles, techniques of production, and chronologies.

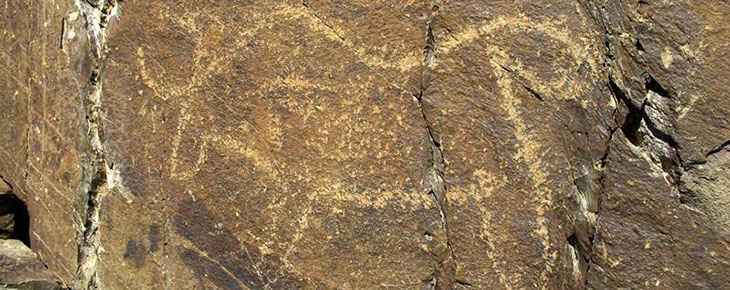

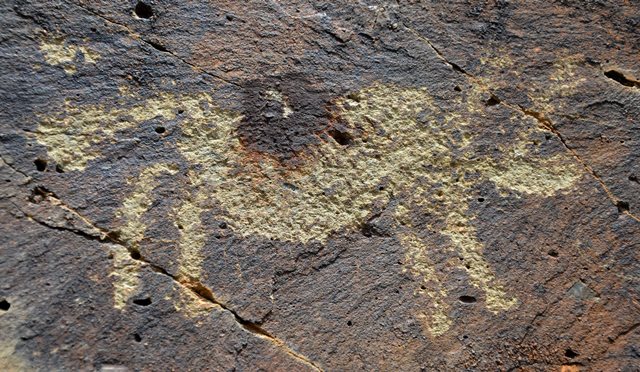

Fig. 1. Lone wild yak

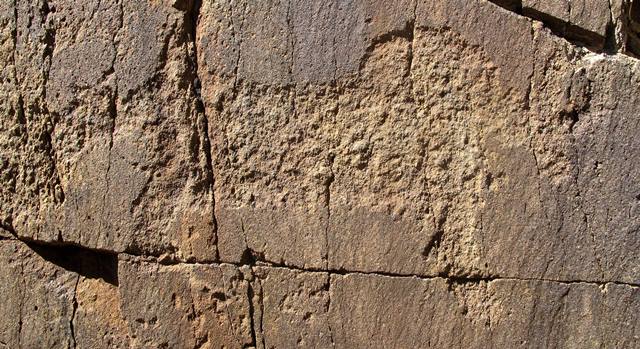

Prominent motifs: short tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; thick, circular horns; elongated rounded snout; S-shaped back; arched belly; two thick, unflexed legs with long rear foot

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated age: Iron Age

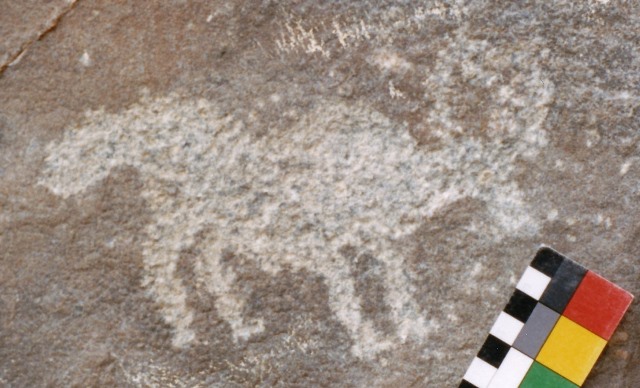

Fig. 2. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with ball-shaped tuft; inward curving thin horns with right angle; rectangular snout; S-shaped back; rounded belly; two flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

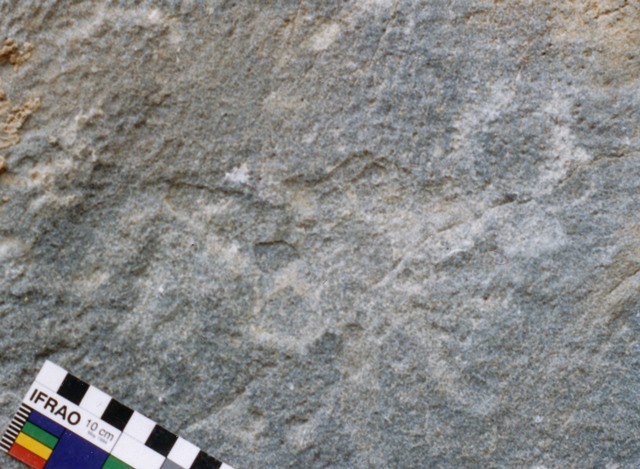

Fig. 3. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with ball-shaped tuft; inward curving thin horns with sharp angle; triangular snout; anterior hump; rounded belly; V-shaped front leg, no rear legs

Body outlined; anterior portion bisected

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age

Fig. 4. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with ball-shaped tuft; thick, circular horns; blunt snout; anterior hump; flat belly; two unflexed rear legs, one flexed front leg with foot, one unflexed front leg.

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age

Fig. 5. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; inward curving horns; triangular snout; S-shaped back; rounded belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 6. Five wild yaks carved in comparable style at various times

Prominent motifs: long tail with ball/slightly splayed tail tuft; inward curving horns; long triangular/rounded snout; S-shaped back; rounded belly; four flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 7. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; inward curving thin horns; rounded snout; anterior hump; flat belly; four long, unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 8. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with ball-shaped tuft; inward curving horns; rectangular snout, gaping mouth; anterior hump; arched belly; four flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, black pigment

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated age: Protohistoric period or Early Historic period

Group 2: Wild yaks with Ball-shaped tail raised upward

This group of wild yak rock art is characterized by subjects with ball-shaped or slightly fanning tails that point upward or are positioned above the back of the animal. This group of wild yaks exhibits a diverse range of motifs, styles, techniques of production, and chronologies.

Fig. 9. Lone wild yak with part of head missing

Prominent motifs: long tail with large ball-shaped tuft; long, slightly curving horns; S-shaped back; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Fig. 10. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with large ball-shaped tuft; converging horns with flared ends; downward pointing snout; small hump; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Fig. 11. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with large slightly oblong ball-shaped tail; thick, inward curving horns; blunt snout; arched back; arched belly; two long, thick, legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age

Fig. 12. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; straight horns with hooked ends; large head; S-shaped back; flat belly; two front legs, V-shaped rear leg

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age

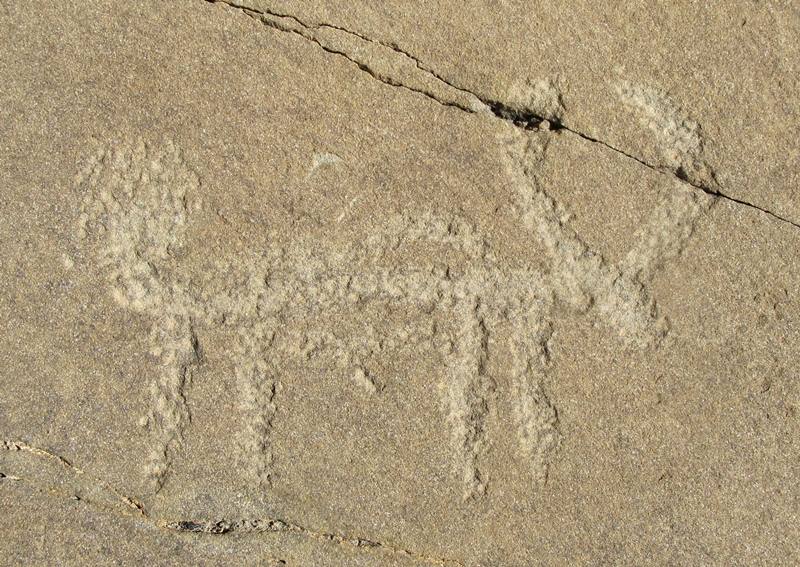

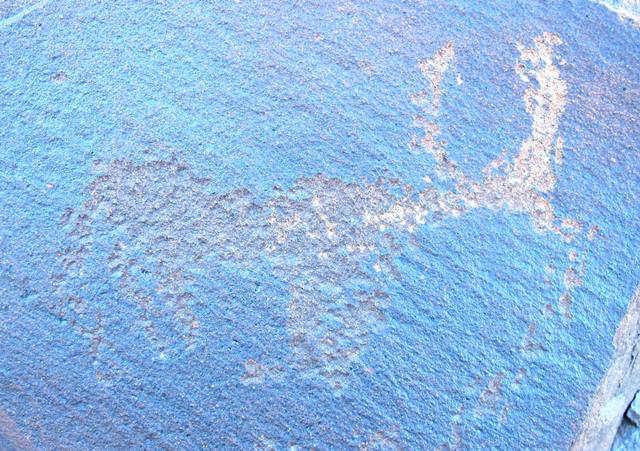

Fig. 13. Two wild yaks

Prominent motifs: short/long tail with large, slightly oblong ball-shaped tuft; V-shaped/inward curving horns; triangular snout; anterior hump; rounded/flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs/two flexed rear legs, two unflexed front legs

Body: silhouetted/partially silhouetted

Technique: deeply/moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age

Fig. 14. Lone wild yak; anterior-most portion of which is missing

Prominent motifs: long tail terminating in large ball-shaped tuft; short, thick, horn; downward pointing head; anterior hump; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age

Fig. 15. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with ball-shaped tuft; thick, circular horns; blunt snout; anterior hump, long neck; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age

Fig. 16. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with ball-shaped tuft; thick, circular horns; rounded snout; anterior hump; rounded belly; two very thick, flexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age

Fig. 17. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with ball-shaped tuft; circular horns; square snout; anterior hump; rounded belly; two thick, flexed legs with foot on rear leg

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 18. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with elongated ball-shaped tuft; large circular horns; rounded snout; small anterior hump; rounded belly; thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 19. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with ball-shaped tuft; inward curving horns; square snout, top of head open; S-shaped back; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 20. Two confronted wild yaks that appear to form a single composition

Prominent motifs: ball tails; circular horns; broad snout; S-shaped back; rounded belly; two thick, flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Changthang

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 21. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; thick, inward curving horns; wedge-shaped snout; S-shaped back; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 22. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with teardrop-shaped tuft; inward curving horns with right angle; square snout; S-shaped back; rounded belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved; tail deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 23. Lone wild yak, part of one horn missing

Prominent motifs: long tail with ball-shaped tuft; inward curving horns; triangular snout; anterior hump; rounded belly; two unflexed rear legs, one thick, unflexed front leg

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

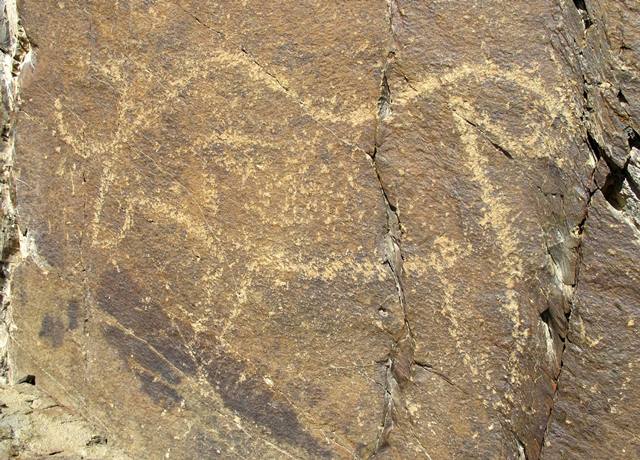

Fig. 24. Two wild yaks that appear to form integral composition

Prominent motifs: long tail with large ball-shaped tuft; double curved horns; rounded/pointed snout; anterior hump; flat belly; four unflexed legs, some with feet

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 25. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with ball-shaped tuft; inward curving horns; rectangular snout; anterior hump; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 26. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; one inward curving horn, one double curved horn; rectangular snout; anterior hump, long neck; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs with long feet

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 27. Wild yak and possible other wild yak (lower specimen) that appear to form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: tail with ball-shaped tuft; thick, inward curving/circular horns; triangular/rectangular snout; S-shaped back/posterior hump; straight/arched belly; two thick, two flexed/unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 28. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; straight horns; rounded snout; anterior hump; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 29. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with large ball-shaped tuft; thick, inward curving horns; no snout, top of head open; anterior hump; rounded belly; two unflexed rear legs, V-shaped front leg

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 30. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with large ball-shaped tuft; circular horns; triangular snout; small anterior hump, long neck; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 31. A pair of wild yaks that appears to form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: long tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; inward curving/circular horns; triangular snout; anterior hump; rounded belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 32. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with ball-shaped tuft; V-shaped horns; triangular snout; anterior hump; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 33. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with ball-shaped tuft; inward curving horns; triangular snout; anterior hump, long neck; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 34. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with large ball-shaped tuft; inward curving horns; rectangular snout; anterior hump; rounded belly; four long, unflexed front legs

Body: outlined with medial partition

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 35. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; forked horns; blunt snout; anterior hump, long neck; flat belly; two V-shaped unflexed legs

Body: outlined, bisected by vertical line

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 36. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with large ball-shaped tuft; V-shaped horns; triangular snout; no hump; arched belly; two long, thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 37. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with ball-shaped tuft; inward curved horns; rectangular snout; small anterior hump, long neck; rounded belly; four long, flexed legs with feet

Body: outlined

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated age: Early Historic period or vestigial period

Group 3: Wild yaks with ball-shaped tail and belly fringe

This group is distinguished by ball tails mostly pointing upward but also oriented in other directions and belly fringes. Specimens in this group mostly date to the Iron Age. However, in terms of motifs, styles and techniques of production, it is quite diverse and is distributed across much of Upper Tibet.

Fig. 38. Lone wild yak, with wild ungulate above and small quadruped to the right that may be part of same composition

Prominent motifs: long tail with large ball-shaped tuft; double curved horns; blunt snout; anterior hump; flat belly with hairy fringe; four unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Late Bronze Age or Iron Age

Fig. 39. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; double curved horns; square snout; anterior hump; flat belly with long hairy fringe; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 40. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with large ball-shaped tuft; circular horns; triangular snout; anterior hump; rounded belly with hairy fringe; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 41. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; inward curving horns; rounded snout; anterior hump; flat belly with hairy fringe; four long, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 42. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; inward curving horns; rounded snout; anterior hump; flat belly with long hairy fringe; four long, flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 43. Lone wild yak with Tibetan A-shaped motif above that may form integral composition

Prominent motifs: long tail with large ball-shaped tuft; double curved horns; rectangular snout; S-shaped back; flat belly with long hairy fringe; four long, flexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 44. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with slightly oblong ball-shaped tuft; thick, inward curving horns; blunt snout; anterior hump; flat belly with hairy fringe; no legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 45. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: short tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; thick, inward curving horns; rectangular snout; anterior hump; flat belly with hairy fringe; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply carved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 46. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with slightly splayed ball-shaped tuft; slightly curving horns; blunt snout; anterior hump; flat belly with hairy fringe; two unflexed rear legs, one V-shaped front leg

Body: outlined

Technique: painted, yellow ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 47. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: long tail with ball-shaped tuft; inward curving, joined horns; square snout; anterior hump; rounded belly with hairy fringe; four long, flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: lightly engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Group 4: Wild yaks with Wedge-shaped tail pointing downward

This group is characterized by wedge-shaped tails that point straight downward or are somewhat raised but still positioned below the level of the back. It is otherwise a diverse group exhibiting a wide range of motifs, styles, techniques of production, and is distributed across Upper Tibet. This group is also fairly diverse chronologically speaking.

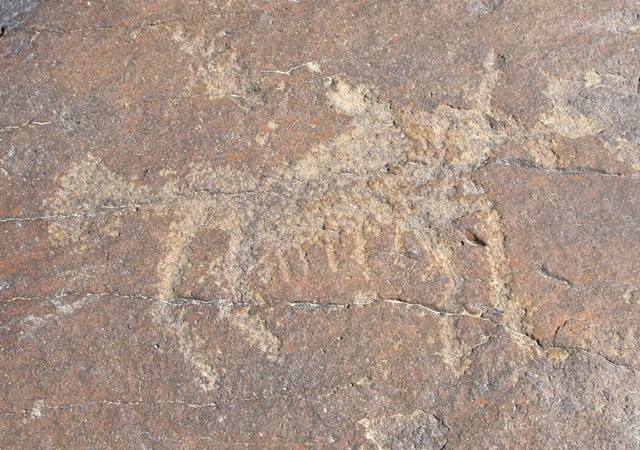

Fig. 48. Lone wild yak with part of tail missing and small quadruped below that may form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; three double-curved horns; rounded snout; S-shaped back; flat belly; three unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 49. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; thick, inward curving horns; square snout; S-shaped back; rounded belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Western Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 50. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; triangular snout; anterior hump; arched belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 51. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; circular horns, top of head open; rounded snout; S-shaped back; rounded belly; two V-shaped legs

Body: outlined

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 52. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; short, thick, horns; triangular snout; S-shaped back; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs with front foot

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 53. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; thick, inward curving horns; triangular snout; S-shaped back; flat belly; two thick, flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 54. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; long, inward curving horns; long snout; S-shaped back; rounded belly; two thick, unflexed/flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 55. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; long, inward curving horns; rounded snout; anterior hump; arched belly; four thick, unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 56. Lone wild yak, head and tail partly missing

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; long, V-shaped horns with flared ends; anterior hump; rounded belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 57. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; long, inward curving horns; blunt snout; S-shaped back; arched belly; four flexed/unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 58. Lone wild yak, anterior portion partially retouched

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; triangular snout; S-shaped back, long neck; arched belly; two thick, flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

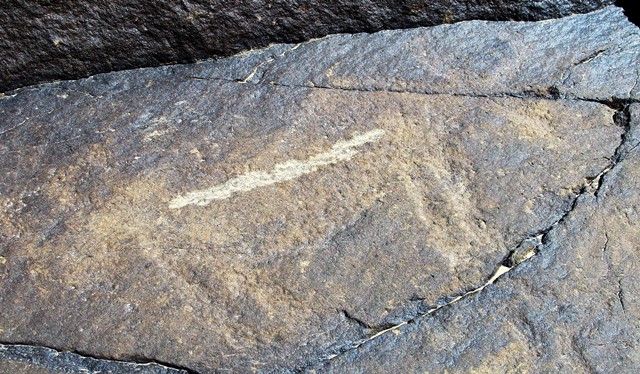

Fig. 59. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; triangular snout; S-shaped back; flat belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 60. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; circular horns; anterior hump; blunt snout; flat belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 61. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; circular horns; S-shaped back; rounded snout; rounded belly; unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age

Fig. 62. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; rectangular snout; rounded belly; two unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 63. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; square snout; rounded belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 64. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; long, inward curving horns; S-shaped back; triangular snout; rounded belly; two long, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: very deeply engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 65. Lone wild yak with Eurasian animal style wild ungulate below that may form an integral composition

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; elongated snout; rounded belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 66. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back, long neck; triangular snout; arched belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 67. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; short, thick, forked horns; S-shaped back; blunt snout; rounded belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 68. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; rectangular snout; rounded belly; two V-shaped legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Iron Age or Protohistoric period

Fig. 69. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; double curved horns; anterior hump; triangular snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: outlined

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 70. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; short, straight horns; anterior hump; long snout; rounded belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 71. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; double curved horns, top of head open; anterior hump; rounded snout; arched belly; two V-shaped legs

Body: outlined, curved line on front part of body

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 72. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; rectangular snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: partially silhouetted, bisected by horizontal line

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 73. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; long, inward curving horns; anterior hump; triangular snout; flat belly; no legs

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Central Changthang

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 74. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; circular horns; anterior hump; rectangular snout; rounded belly; four long, flexed legs with feet

Body: partially silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 75. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; rectangular snout; rounded belly; four flexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: moderately engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 76. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; square snout; rounded belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: lightly engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 77. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; square snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs with feet

Body: outlined

Technique: lightly engraved

Region: Far Western Tibet

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period

Fig. 78. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; anterior hump; rounded snout; arched belly; two thick, unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period or Early Historic period

Fig. 79. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; thick, inward curving horns; anterior hump; elongated snout; flat belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre, black pigment on horns and head

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Protohistoric period or Early Historic period

Fig. 80. Lone wild yak

Prominent motifs: wedge-shaped tail; inward curving horns; S-shaped back; square snout; rounded belly; four unflexed legs

Body: silhouetted

Technique: painted, red ochre

Region: Eastern Changthang

Estimated Age: Early Historic period or Vestigial period

Next Month: More wild yak rock art and other surprises!