April 2016

John Vincent Bellezza

This month’s Flight of the Khyung is ready for takeoff! The destination is ancient western Tibet. From tea drinking to stone houses to primitive art, we shall take in a veritable medley of sights, ideas and information. Let us begin our flight with a review of a scientific paper that received considerable media coverage in January of this year. In the second and final article of this issue, the horned eagle explores an ancient settlement adorned with rock art.

A Review of a Recent Scientific Article: “Earliest tea as evidence for one branch of the Silk Road across the Tibetan Plateau”

This is a review of an article that appeared in the January 7, 2016 issue of Nature Scientific Reports, an open access journal published by nature.com. I shall briefly describe the findings of this landmark study, and furnish complementary archaeological data as well as an analysis of its historical and cultural significance. The work concerned is:

Houyuan Lu, Jianping Zhang, Yimin Yang, Xiaoyan Yang, Baiqing Xu, Wuzhan Yang, Tao Tong, Shubo Jin, Caiming Shen, Huiyun Rao, Xingguo Li, Hongliang Lu, Dorian Q. Fuller, Luo Wang, Can Wang, Deke Xu and Naiqin Wu. 2016. “Earliest tea as evidence for one branch of the Silk Road across the Tibetan Plateau”, in Nature Scientific Reports. For access:

http://www.nature.com/articles/srep18955

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4704058/

The discovery by Chinese archaeologists of a biomolecular signature (comprised of traces of caffeine, theanine and calcium phytoliths) for tea in a tomb at Gurgyam, confirms the existence of a physical exchange between southwestern China and western Tibet around 1800 years ago. Until this find, the earliest recorded importation of tea to Tibet coincided with the Tang dynasty and Tibet’s Imperial period. Findings of the Houyuan Lu et al. article suggest that a branch of the pre-classical Silk Road penetrated western Tibet, connecting this rugged mountainous region to the wider cosmopolitan world of Central Asian and East Asian cultures and civilizations.

The Houyuan Lu et al. study also notes the discovery of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) residue in the Han Yangling Mausoleum near Xi’an, dated to circa 200 BCE. This is among the earliest physical evidence in the world for tea as a culturally useful material. Xi’an once formed the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, a broad and shifting network of trade routes and artistic and intellectual interchange linking China, Central Asia and Europe in antiquity and premodern times.

Both imported materials and the rich ensemble of indigenous objects discovered in the tombs of Gurgyam confirm that western Tibet possessed a sophisticated material culture long before its conversion to Buddhism 1000 years ago. According to Houyuan Lu et al., tea in the Gurgyam burial was accompanied by vegetal traces (lemma phytoliths) of barley (Hordeum vulgare). This seems to document the presence of what is called pak (spag), a staple food in historical-era Tibet, consisting of tea and parched barley meal kneaded together into a paste. It is likely that this edible mixture was deposited in the tomb as provisions for the dead in the afterlife, as part of an elaborate series of funerary rites. The use of barleycorn and barley cakes in funerary rites is attested in Old Tibetan literature.

Artifacts made from cane and birch bark recovered from the burials of Gurgyam and other cemeteries in Guge (western Tibet) indicate that trade in common materials crossed over the Himalaya Range from northern India. Similarly, the diverse assortment of stone beads discovered at Gurgyam and the nearby Khardong (mKhar-gdong) citadel point to India and other territories. Thus an extensive exchange network encompassed western Tibet some 1800 years ago, extending from China to north Inner Asia (Xinjiang, Mongolia, southern Siberia, and the Pamirs) and the Indian Subcontinent. As part of an economic regime of comparative advantage, western Tibetans are likely to have introduced their own raw materials into this vast network. These may have included gold, musk, wool, borax, salt, medicinal and other economic plants, and other sought-after commodities.

According to Houyuan Lu et al., the presence of tea indicates that a Silk Road trade artery ran across the Tibetan Plateau from southwest China all the way to Ngari (mNga’-ris) in western Tibet. The authors of the work consider this route a precursor to the “Tea Horse Road”, which passed through Yunnan, beginning as early as the seventh century CE. There is mounting evidence to indicate that it was used to trade tea, horses, furs and medicinal plants between eastern Tibet and western China.

A so-called Tea Horse Road as a major conduit conveying trade goods far onto the Tibetan Plateau during the Tibet Imperial period (circa 650–850 CE) can be readily seen in the context of interactions between the two important regional empires of that time, Chinese (Tang) and Tibetan (sPu-rgyal). Nevertheless, further archaeological and textual study is required to properly gauge the geographic extent and economic impact of such trade links.

Virtually nothing is yet known about the potential existence of an analogous trade network traversing the Tibetan Plateau in the Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE). This is due to a lack of archaeological investigation and focused textual analysis. For the Protohistoric period, no epigraphic or archaeological evidence for appreciable Chinese cultural inputs has been detected in either central or western Tibet, the Tibetan cultural heartland. As my long-term research demonstrates, there is significant evidence, however, for north Inner Asian technological and cultural influences having had a profound effect on the Tibetan heartland.

That tea was discovered near Xi’an, the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, suggests that any movement of this product further west occurred via the geographically crucial Hexi Corridor and onward along well-established migratory routes to Xinjiang (Eastern Turkestan). Xinjiang was a key center on the Silk Road of pre-classical and classical times, linking Central Asia and China. The discovery of silks in Gurgyam tombs from the same time period as tea supports the existence of such an avenue of exchange (for more information on these silks, see October 2010 and April 2012 Flight of the Khyung). Silk as trading or diplomatic articles of Inner Asian or Chinese manufacture must have come to western Tibet via northern intermediaries, for similar silks have been discovered at Niya, Loulan, Shampula and other sites in Xinjiang.

Bronze metallurgy on the Western Tibetan Plateau (western Tibet, Ladakh, Spiti, etc.) in the Iron Age (700–100 BCE) also exhibits pronounced northern technological and cultural influences, with Xinjiang probably playing a significant role in its transmission southward (see March 2016 Flight of the Khyung). The use of golden burial masks in both Xinjiang and western Tibet during the Protohistoric period, also indicates that fundamental cultural themes diffused between these two regions (on these masks, see November 2011 and November 2013 Flight of the Khyung).

Trade and commerce as factors in the initiation and maintenance of ideological and technological exchanges encourages us to see the movement of goods and ideas as closely allied phenomena. Although vectors of ideological and technological transference do not per force parallel lines of trade, they do document the directionality of people to people contacts. In any case, interregional relationships are underpinned by at least some economic activity. At minimum, an effective system of transport and other logistical support is needed to sustain contacts between disparate peoples over large territories.

In light of the archaeological findings and economic considerations reviewed above, we must consider the prospect that the tea recovered in Gurgyam reached there from Xinjiang. This entry point seems to correlate better with the evidence gathered thus far, rather than postulating a system of circulation spanning the Tibetan Plateau.

A northern exchange nexus does not negate the likelihood that in early times the Western Tibetan Plateau was integrated into an exchange system embracing other parts of the Tibetan Plateau as well. However, the prevalence of subsistence tribal economies and difficult terrain in southeastern Tibet may have restricted the conveyance of tea from southwestern China directly across the Plateau. If a trade conduit traversing the Tibetan Plateau was responsible for the transport of tea to Gurgyam, it is more liable to have passed through Qinghai (Amdo) and the Changthang (Byang-thang), a geographically and ethnically interconnected expanse of lofty plains.

Moreover, there is no proof yet that tea was a widely traded beverage in western Tibet 1800 years ago. The trace amounts recovered in a single burial could signal that it functioned as a prestige good for special ritual purposes only. If tea was indeed reserved for the funerals of the social elite of the region, alternative forms of exchange (religious, diplomatic, benedictory, tributary, etc.), instead of economically driven models, may be responsible for its appearance in Gurgyam.

A definitive judgment on precisely how tea reached western Tibet 1800 years ago will only come about through dedicated study of ancient economic and social activities in Tibet. Essential elements of a study on patterns of exchange include GIS analysis, field surveys and remote sensing to ascertain agents of transmission on a regional scale, as well as the development of a sound theoretical framework. On a broader level, the challenge before us is to more accurately chart the formation and development of the ancient web of trade and exchange undergirding Inner Asia, one that does not neglect the Tibetan Plateau.

Art and Shelter: An ancient settlement in far western Tibet

I have documented dozens of pre-Buddhist settlements in western Tibet over the last two decades. However, there is still one special residential site to be catalogued. It is located in Guge, just below the large esplanade that runs along the foot of the Ayila Range. These Transhimalayan mountains form part of the northern and eastern borders of Guge. For the purposes of this article, we shall call the settlement featured in this article “Rock Art Village”.

Fig. 1. The site of Rock Art Village in Guge, western Tibet. Most of the walls visible in the image were reconstructed for use as a livestock corrals. The rim of the esplanade is just behind the ridges enclosing the site.

As the name indicates, Rock Art Village is full of rock carvings (petroglyphs). They date to the Early Historic period (650–1000 CE) and possibly the Vestigial period (1000–1250 CE). Here, on rocky shelves interspersed between steep slopes, are the faint remains of three interconnected levels of buildings. These structures were constructed with all-stone corbelled roofs. Approximately 250 m below the ancient settlement is a small river winding through a canyon. This canyon is one of the scores that make up the rugged badlands of Guge.

Fig. 2. Rock Art Village with the badlands of Guge in the background. The level area in the foreground was once part of an upper tier residence now levelled to the ground. On the large boulders surrounding the flat patch are various petroglyphs. In the middle of the photo are stone roof members resting on structures belonging to the middle and upper tiers of the site.

Very little of Rock Art Village remains intact. At some point in time, the ancient complex of residences was dismantled in order to build livestock corrals. Nevertheless, sufficient vestiges in the form of heavy footings, wall fragments, corbels, bridging stones, and niches have survived, identifying the site as an erstwhile permanent settlement. It is one of several in Guge boasting all-stone corbelled roofs, a style of construction once used in Upper Tibet as far east as Namru (gNam-ru).* This type of architecture ranges in size from tiny huts to massive castles 150 m and more in length. All-stone corbelled structures characteristically have meandering ground plans, tiny doorways, buttresses subdividing rooms, and windowless walls, a tradition of construction and domestic ecology that fell out of favor with the rise of Buddhism in Tibet.

For studies of this type of architecture, see my:

2015. “The Ancient Corbelled Buildings of Upper Tibet: Architectural attributes, environmental factors and religious meaning in an unique type of archaeological monument” in “Architecture and Conservation: Tibet”, November 2015 (ed. Hubert Feigelsdorfer) pp. 4–19. Journal of Comparative Cultural Studies in Architecture. Special issue from proceedings of the International Association of Tibetan Studies XIII, Ulan Bator.

http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/pdf/Bellezza_JCCSA.pdf

2014. Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: A Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites on the Tibetan Upland, Residential Monuments, vol. 1. Miscellaneous Series – 28. Sarnath: Central University of Tibetan Studies. Online version, 2011: Tibetan & Himalayan Library (THlib.org). http://www.thlib.org/bellezza

2008. Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet. A Historical and Ethnoarchaeological Study of the Monuments, Rock Art, Texts and Oral Tradition of the Ancient Tibetan Upland. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse Denkschriften, vol. 368. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

2002. Antiquities of Upper Tibet: An Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Archaeological Sites on the High Plateau. Delhi: Adroit.

2001. Antiquities of Northern Tibet: Archaeological Discoveries on the High Plateau. Delhi: Adroit.

All-stone corbelled architecture in Upper Tibet has been dated to the Iron Age (700–100 BCE) and Protohistoric (100 BCE to 650 CE). Transitional forms influenced by Buddhist building traditions continued to be raised in the Early Historic period (650–1000 CE). Transitional forms of corbelled architecture have taller entranceways, larger rooms and a few windows. Some functioned as Buddhist temples.

Rock Art Village appears to have consisted of a conterminous group of buildings and rooms but too little structural evidence persists to know for certain. The original size of the complex is unclear. It may once have been home to dozens of people. The ruins can be divided into three zones: lower tier, middle tier and upper tier.

Fig. 3. A view of the middle tier of Rock Art Village. The still used corral in the foreground was constructed from stones extracted from the ancient settlement. Rock art covers the larger boulders.

Given the relative exclusiveness of all-stone corbelled edifices in Upper Tibet, it can be inferred that Rock Art Village was occupied by an elite sector of society. Its out-of-the-way location suggests that it was built to avoid detection. Many corbelled complexes in Upper Tibet have hidden or hard-to-reach locations as if defense was a major preoccupation.

From my reconnaissance of the ruins very little can be said about the household makeup Rock Art Village. It is not known whether it housed biological families, a local ruling clique or a religious fraternity. A more in-depth archaeological study is required to determine household composition and other vital matters related to all-stone corbelled buildings in Tibet.

Fig. 4. Fragmentary walls of the middle tier of Rock Art Village. The lintel over the entranceway of a partially intact rear chamber is visible in the middle of the photo.

Fig. 5. The east section of the middle tier rear wall with the remains of two niches, a telltale architectonic feature of corbelled buildings in Upper Tibet.

Fig. 6. The partially intact chamber in the middle tier of Rock Art Village. Note the random-rubble wall fabric and lack of mortar. This may originally have been a dry-wall structure but it is too degraded to know for certain. This tiny room constituted a small part of the middle tier structures, the forward portions of which are entirely obliterated.

The middle tier of Rock Art Village appears to have been the most extensive and has the larger of two corrals established on the site. This corral is used on a seasonal basis. Only parts of the rear wall of the ancient buildings endure. This now fragmentary wall was at least 14 m in length and was heavily constructed with stones up to 1.2 m long. Robust wall construction was needed to support the very heavy stone roofs. On its west end, the rear wall is around 2 m in height and built against a rock face. Along this portion of the wall there is a chamber that is too small to have been used as a living space. It may have had storage or ritual functions. This chamber has an intact lintel spanning the entranceway (1.2 m x 60 cm). On its east end, the rear wall is set 2 m below the slope. This indicates that the building it was once a part of had a semi-subterranean aspect, as is common in all-stone corbelled architecture. The east portion of the rear wall contains two partially intact niches, another architectonic trait defining corbelled structures in Upper Tibet.

Fig. 7. A view of the one partially intact upper tier room in Rock Art Village. Note the in situ roof slab (foreground) and bridging stone (right side). These lithic members originally rested on corbels, most of which are now missing. It can also be seen how deeply set into the ground the room is. This would have made it easy to heat and enhanced its structural integrity and durability.

Fig. 8. The bridging stone still in place on the roof of the upper tier chamber.

Fig. 9. The four niches in the rear wall of the upper tier room.

Elevated 70 cm above the rear chamber of the middle tier is the one partially intact room (3.3 m x 3.3 m) of the upper tier. It was built against a rock outcrop, as such structures often are. Its rear wall is set 1.9 m below ground level and has four small niches in it. It is not clear how these niches were used. Perhaps lamps for illumination were placed in them. On the upper portion of the rear wall are soot deposits from ancient fires. There is a bridging stone (1.4 m long) still clinging to the roof and a corbel protruding 15 cm from the forward wall of this crumbling room.

Fig. 10. Site of the lower tier of Rock Art Village.

Fig. 11. An intact wall fragment of the lower tier. The careful double-course construction of this wall shows that it once belonged to a building.

The lower tier of Rock Art Village is situated directly below its middle tier. A 5 m-long portion of the robust outer south wall has endured. It is around 80 cm thick and rises 1 m on its exterior side and 50 cm on the interior.

Fig. 12. An ancient naturally-occurring foundation stone pullulating with carvings. In the background are structures of the middle and upper tiers of Rock Art Village. On the boulder are wild yaks and other wild herbivores. There is an anthropomorphic figure visible in the middle of the rock face. Also, note the square with an X in it on the lower right side of the boulder.

Fig. 13. Vertically oriented panel of a boulder with carvings of wild yaks and other animals. Early Historic period.

Fig. 14. Close-up of what appears to be two wild yaks in fig. 13. They were rendered using different shallow carving techniques.

A very unusual feature of Rock Art Village is the petroglyphs added to boulders that once formed part of the foundations of the buildings. These boulders now demarcate the corrals of the site. This rock art exhibits typical Upper Tibetan styles and themes and is mostly composed of zoomorphic subjects. Among more than two hundred rock carvings at the site, wild yaks and sheep and other wild herbivores predominate.

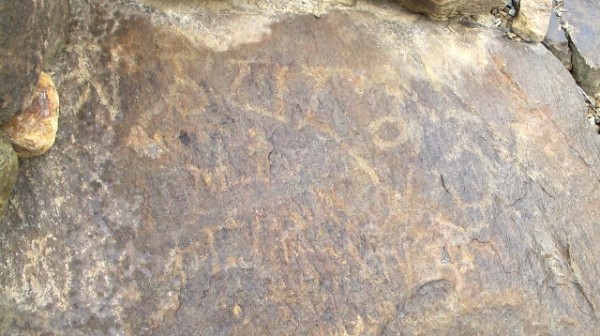

Fig. 15. Incomplete mani mantra inscribed on the face of a boulder. The paleographic traits of this inscription indicate that it dates to the Early Historic period or perhaps somewhat later (Vestigial period).

The rock art of Rock Art Village is by and large stiff in form and roughly cut. It was made by a superficial bruising or scratching of the stone surface. This art lacks the vitality and boldness of earlier rock carvings in the region. More ancient rock art of Upper Tibet is often adroitly carved and of masterful execution. The stylistic and technical qualities of petroglyphs from Rock Art Village indicate that they can be attributed to the Early Historic period and as late as the Vestigial period. This chronological attribution is corroborated by inscriptions of the six-syllable mani mantra and Om syllable found at the site.

Fig. 16. Wild sheep and other wild ungulates, Early Historic period.

Fig. 17. Wild yak and another animal that appear to form an integral composition, Early Historic period.

Fig. 18. An older carving of a wild yak found in close proximity to Rock Art Village. This petroglyph appears to date to the Iron Age. Note the barbed belly fringe, a characteristic motif of wild yak rock art in Upper Tibet. This yak was more adeptly carved than later examples of rock art at Rock Art Village. It also has a more developed patina, an indication in this case of advanced age.

Rock art dating to the Early Historic period in Upper Tibet belongs to a decadent phase in its production. This was a time when the dexterous modeling of figures gave way to cursory approaches to depiction. Older rock art exhibits a much broader range of manufacture techniques including deep engraving, controlled chiseling and fine pecking. These techniques were not used in rock art of the Early Historic period. Moreover, rock art of the Early Historic period has a restricted selection of subjects and themes. For example, big game hunting scenes, which dominate much prehistoric rock art in Upper Tibet, is mostly absent in the repertoire of the historic era. In fact, there does not seem to be a single hunting portrayal at Rock Art Village.

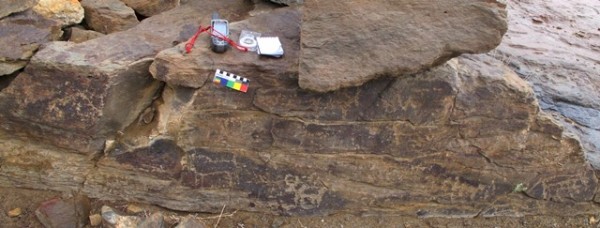

Fig. 19. Vertical face of boulder with many carvings on it, most of which are indistinct and crudely made. Below the color calibration card is a horseman. Note the sacred syllable Om roughly inscribed on the bottom left side of the image.

Fig. 20. Close-up of horse rider in fig. 19.

Fig. 21. The syllable Om on another boulder. This figure exhibits archaic paleographic characteristics such as the pronged style of the front portion of the letter A (for other examples, see January 2011 Flight of the Khyung, figs. 12, 13). This inscription could have been made by either Buddhists or followers of what is generically called bon. Nonetheless, it more likely that it was made by non-Buddhists.

Fig. 22. A counterclockwise swastika. This symbol was probably carved by a non-Buddhist.

The petroglyphs of Rock Art Village contain subjects encountered in more ancient rock art of Upper Tibet, indicating a significant degree of cultural continuity. The depictions of wild ungulates, horseman, anthropomorphic figure with outstretched arms and legs, swastika, and square with an X at Rock Art Village are represented in carvings and pictographs of antecedent periods. We can see such reoccurring figures as iconic representations epitomizing the cultural complexion of Upper Tibet.

The presence of rock art at the site of all-stone corbelled buildings may furnish some indication of when the settlement fell into decline. It appears that the carving of foundation stones occurred after the residential structures were abandoned because a profusion of rock art is not associated with other such sites in Upper Tibet. Where rock art does occur, it appears as an afterthought, added to archaic residential centers after their dereliction as a kind of graffiti. In the case of Rock Art Village, petroglyphs may have been made with the conversion of the site to other economic functions. This may possibly have to do with pastoralism. Pastoralism as a theme rarely appears in the rock art of Upper Tibet, so no such signal would be obvious.

Next Month: The Magnificent Swastika in All its Permutations in the Rock Art of Upper Tibet!