March 2011

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to the new tibetarchaeology.com website! It has been expertly designed and created by my friend Sally Walkerman. I think you will find it a significant improvement over the old website. Now you can now actually sign up to have this newsletter delivered to your inbox monthly.

This Flight of the Khyung delivers more of the archaeological gems of Tibet right to your doorstep. From pillars to paintings to sculptures, come away with the horned eagle to a world far removed from the modern.

Let me also take this opportunity to wish readers, each and every one of you, a very pleasing Year of the Iron Rabbit!

Walled-in pillars of the heights

Last month, Flight of the Khyung looked at the impressive concourses of pillars appended to temple-tombs of upland Tibet. This month’s issue features another type of pillar monument that sharply defines the ancient Upper Tibetan cultural sphere. This is the single pillar or line of pillars enclosed by four low-lying walls. As with the fields of pillars, these standing stones are funerary in nature. Ritual in function, they mark sites where burial rites and perhaps commemorative observances were held. The pillars and walls are often found amid burial grounds of various kinds, ranging from small tombs with hardly any protrusion above the surface to large mounds ostensibly used for the internment of high status individuals.

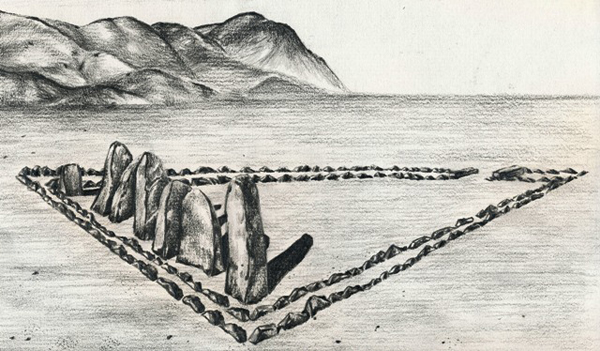

Fig. 1. A reconstruction of the basic features of walled-in pillars, an artist’s conception

Standing stones were firmly planted in stone pens in a wide range of Upper Tibetan localities. This was standard monumental currency in pre-Buddhist Upper Tibet, but not in other regions of the Plateau. Given their geographic distribution, the walled-in pillars can be spatially correlated to Zhang Zhung, the ancient kingdom of Tibetan literary sources. The use of such vertical stones brought highland western and northern Tibet into cultural correspondence with north Inner Asian regions, where menhirs were being erected from the Bronze Age until the 7th century CE, and even later in Kirghiz cemeteries.

The Upper Tibetan pillars, menhirs or stelae (Tibetan: doring / tho) rise 15 cm to 2.4 m above the ground surface, with as much as 2/3 of their length concealed underground. The pillars are a study in form; some were neatly hewn while others are raw chunks of rock. The type of rock used depends on what was available locally and varies greatly, with many different colors and textures embellishing ancient cemeteries. These pillars have square, rectangular, triangular and irregular cross-sections, a who’s who of verticality. Some enclosures have just one pillar while others host 20 or more standing stones.

The stone pens in which the pillars are housed were built on level ground and range greatly in size. The largest enclosures are 15 m or more in length. The four walls of an enclosure are made of parallel courses of stones embedded securely in the ground. These walls are either flush with the surface or extend above it in several layers of stones. The enclosures are usually aligned in or close to the cardinal directions. Pillars almost always stand near the inner west wall of an enclosure.

Astrological and astronomical calculations are implicit in the alignments of the walls and pillars, but what exactly ancient Tibetans had in mind cannot be determined with any assurance. It may be that alignments marked the season in which outlying burials were made. That burial was to take place at prescribed times is noted in Old Tibetan funerary documents. Alternatively, orientation in the compass points may have been seen as crucial in rites designed to free the dead from a demon-ridden postmortem morass. Old Tibetan funerary texts speak of the physical nature of passage to the celestial afterlife and the need of funerary priests to actually chart a course for the deceased to follow through an imagined landscape.

Traditionally, the walled-in pillars were usually avoided by local residents out of respect for the spirits that might be dwelling there. They were also given a wide berth because they are sometimes seen as the funerary sites of that elusive non-Buddhist ancient tribe known as Mon. Nowadays, however, with all the house building, sociopolitical change and erosion of traditional values underway, these enchanted archaeological sites are increasingly threatened. The lack of a coherent conservation strategy is only exacerbating the problem. Fortunately, the looting of tombs, a growing problem in Upper Tibet, does not much affect the penned pillars as they do not appear to be sepulchral. Enclosures excavated by herders in the 1980s turned up sheep horns, the bones of herbivores and little else.

According to the pastoralist communities of upland Tibet, the pillars erected within quadrate enclosures emerged at the very beginning of the universe. While this may be quite an exaggeration, the oral tradition does signal great age. Timbers removed from inside a wall of a mausoleum built with an analogous enclosure have been dated to circa the 5th century CE, furnishing us with a scientific perspective on which to build. Some walled-in pillars are liable to extend much further back in time perhaps to the first half of the first millennium BCE (on cross-cultural comparative grounds). On the other end of the chronological spectrum, certain examples may have been maintained or even built in early historic times (650–1000 CE). Until these monuments can be properly excavated by archaeologists, this is the 1500-year wide bracket of time on which the walled-in pillars must be hung.

All the photographs of walled-in pillars shown below were taken on my 1999 and 2000 expeditions. For more recent discoveries including some of the most impressive examples, please see the Antiquities of Zhang Zhung website www.thlib.org/bellezza (still not finished but getting close).

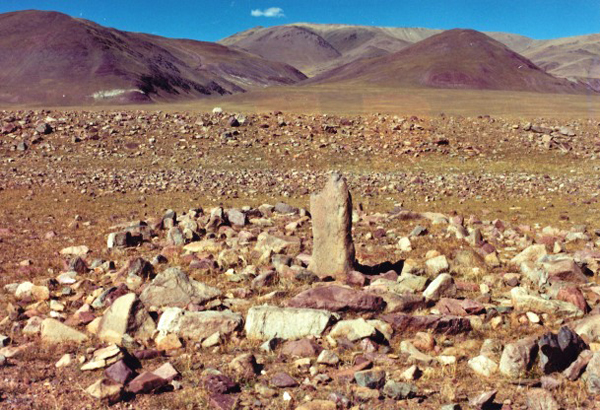

Fig. 2. Two pillars sit at the west end of a disintegrated enclosure. This site in the central Changthang is unusual in that it was built relatively close to a watercourse, albeit on well-drained ground

Fig. 3. Another example of walled-in pillars in which only fragments of the enclosure remain

Fig. 4. A fairly small enclosure (7 m x 4 m) with a solitary stele that was broken long ago. Now standing 1 m in height, the break has eroded smooth. The pen was robustly and carefully constructed with large stones

Fig. 5. Walled-in pillars found with the assistance of a local drokpa family. They were keen to show me this magical place but not too keen on photography

Fig. 6. Light and dark-colored pillars inside an enclosure overlooking a salt lake in the central Changthang

Fig. 7. This site is known as Loro Doring. This pillar monument is situated at the edge of the new highway that extends from central to western Tibet. In the last couple of years this site has been heavily impacted by road construction crews. Although the highway bypasses it, the enclosure was excavated and for no apparent reason

Fig. 8. At this site in the western Changthang only large pillars remain, the area having been disturbed by the construction of a herder’s hamlet

Fig. 9. These wall-in pillars happened to be found where a Kagyu monastery was built in the early 20th century. The monks regard the site as having special properties and instruct Tibetans not to litter or do anything else that could have a negative impact on it

Fig. 10. These walled-in pillars in western Tibet were erected near other types of funerary structures, including a mausoleum that once had a concourse of pillars appended to it (situated directly behind the walled-in pillars). This important archaeological site in the upper Indus valley was converted into a pastoral camp in pre-modern times

Fig. 11. Here is a row of ancient standing stones that can hold its own with modern sculpture

Fig. 12. Two fairly large and well-formed menhirs (1.5 m and 1.3 m in height) erected inside a spacious enclosure (11 m x 19 m)

Fig. 13. At 2.4 m, this is the tallest pillar of its kind discovered in Upper Tibet. Reportedly, the enclosure and several other large well-hewn pillars were destroyed in the Chinese Cultural Revolution during a failed agricultural project.

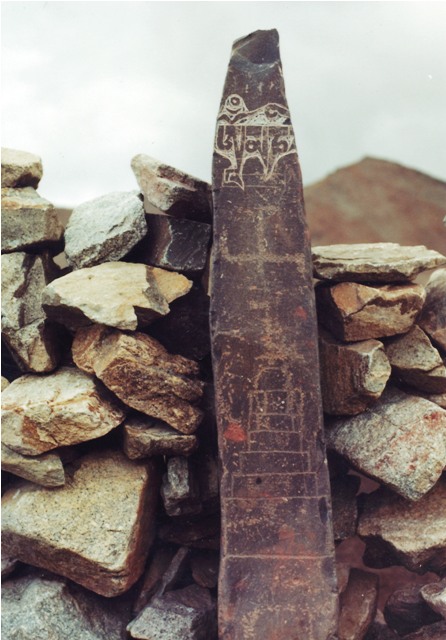

Fig. 14. One of a number of pillars in northwestern Tibet integrated into a corral. Presumably there was once an enclosure as well. This particular specimen was engraved with a swastika and two primitive shrines at different times long ago. In contrast, the letters Om’ ma ni at the top of the stele were carved at a much later date, as indicated by the relative level of erosion exhibited by the various carvings

Fig. 15. One of the only surviving pillars of a site known as Shang Doring, in the western Changthang. By all accounts, this was an exceptional site that boasted several enclosures and many large pillars. Shang Doring was dismantled in the Chinese Cultural Revolution to build administrative facilities

Fig. 16. This trio of pillars in the eastern Changthang is known as the ‘Three Brothers’. In this region of Upper Tibet there are no walled-in pillars but rather a few sites with isolated pillars. The geographic demarcation of the walled-in pillars and less common isolated pillars seems to coincide with the dividing line between the pre-7th century CE proto-nations of Zhang Zhung and Sumpa, as identified in Tibetan literature

The biggest pictograph in Upper Tibet

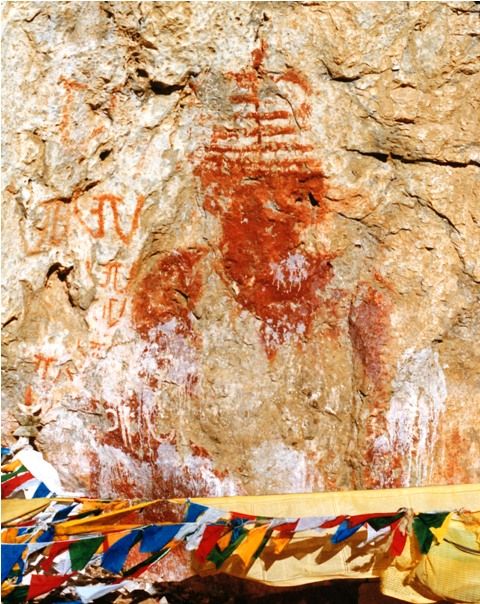

Red ochre pictographs come in a great profusion of styles and subject matter in Upper Tibet. They also vary significantly in size. The largest example documented to date consists of an early style chorten shrine that measures approximately 5 m in height and 2 m in width!

Fig. 17. Much of this giant red ochre chorten has disappeared over time. It appears that it was also literally whitewashed in order to remove its presence. The squat pyramidal spire and broad midsection and base are design traits of archaic shrines. This is corroborated by the inscription to the left of the chorten in which the Tibetan letter A has been written vertically several times. These large letters were inscribed in the same ochre hue and exhibit similar wear characteristics as the chorten, suggesting that they date from the same timeframe. The style of calligraphy is archaic and could well date to the early historic period. The chorten may possibly be ascribed to the early historic period but, in any case, it was painted before circa 1250 CE and the definitive Buddhist conquest of the region. This shrine and inscription were almost certainly made by those belonging to a non-Buddhist or bon cult

Lion fixed, lion movable: ancient Tibetan feline sculpture

The lion was one of the most popular and revered of ancient Tibetan emblems and motifs. Here we will briefly survey just two examples.

Fig. 18. This is the famous stone lion of the Chonggye (’Phyong-rgyas) royal burial grounds in southern Tibet. It is approximately 1.5 m in height and found near the burial mound of King Dusong Mangpoje (’Dus-srong mang-po rje), who lived between circa 676 and 704 CE. This lion sculpture must have been installed at the tomb as a guardian and royal status symbol. Protective gods of the dead in the shape of lions are noted in archaic funerary rituals of the Bon religion.

The squatting lion of Chonggye in form and aspect strongly resonates with lion sculptures of the Tang dynasty. Analogous esthetic traits may indicate that leonine art in Tang China and in imperial Tibet were informed by one another. Given the historical anchorage of the lion in Tibetan culture, I see no reason to postulate Tang China as the sole artistic source for the Chonggye lion, as is supposed by some Chinese scholars. In fact, the sinuous flow of the mane and shape of the head of the Chonggye specimen appear to derive from Persian art. Tibet is geographically proximate to the cultures of southern, western and central Asia, lands where lions once lived. In prehistoric times, lions may even have ranged in the valley systems of far western Tibet. It is commonly held by Western art historians that the lion motif first arrived in Tibet with Buddhism but this is certainly not the case. While Buddhist art was clearly an enriching factor in terms of depiction and application, the lion enjoyed a seminal position in the older clan and religious lore of Tibet. The culturally ingrained nature of this noble beast in Tibet is reflected in the wide variety of ancient feline forms found in rock art and among small copper alloy objects known as thokchas. The origins and development of lion art in Tibet is a subject that deserves closer attention than can be given here. I shall return to it at a later date. For more information on the extremely precious Chonggye lion, see the relevant article by the late H. E. Richardson in his collected works, High Peaks, Pure Earth.

A comment on a recent archaeological find in Nepal

The discovery of human remains in a cliff in Mustang (near the Upper Tibetan border) has just been splashed across the media. It is part of a publicity drive, orchestrated by savvy marketing men. As the flesh was ritually stripped from the bones, those involved in the Mustang find cite Zoroastrianism as a possible source for this mortuary custom. However, I see no cause to go so far afield, in trying to understand the cultural affinities of the Mustang burial. In fact, in an Old Tibetan funerary document, the custom of removing the flesh and organs of corpses is documented (see Zhang Zhung, pp. 501, 502). There is also considerable archaeological evidence for the practice of excarnation in Upper Tibet. This involves the ritual preparation of bare bones for deposition in ossuaries (see Antiquities of Zhang Zhung). On the other hand, solid evidence for Avestan or other forms of ancient Persian culture are not discernable in the monumental record of Upper Tibet.