December 2015

John Vincent Bellezza

Flight of the Khyung welcomes you to the ancient strongholds of Spiti! Before we head to the summits though, my felicitations. A number of auspicious observances are held around the winter solstice worldwide. So, with that in mind, I wish all readers a great holiday season whatever your faith or understanding!

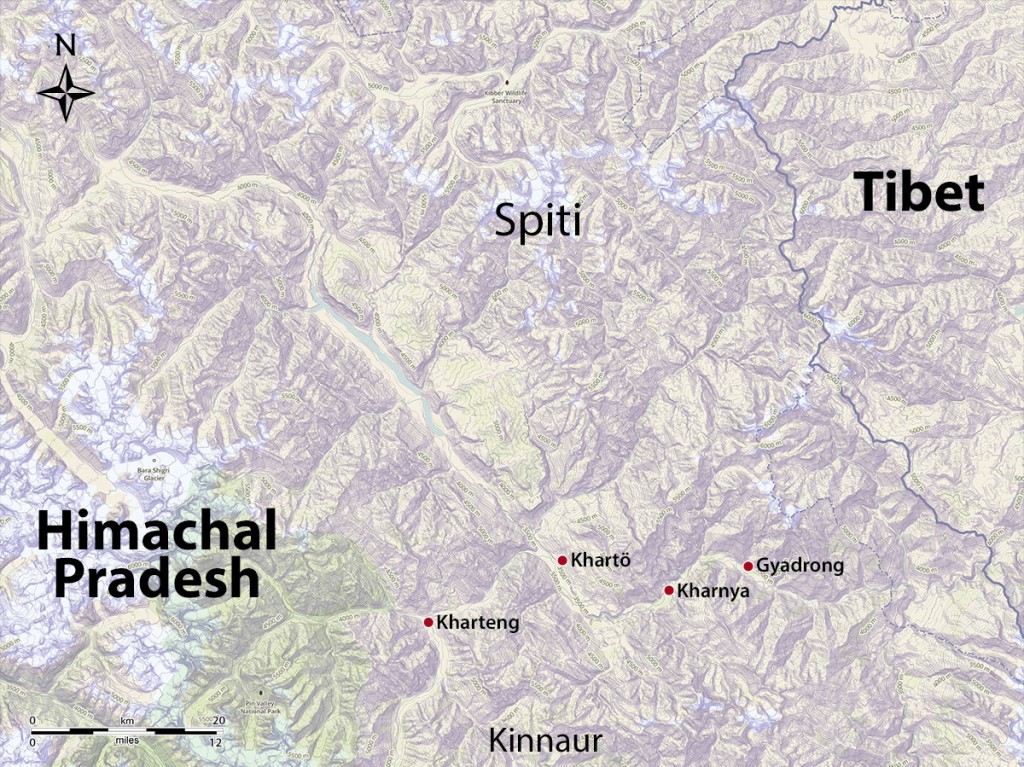

On this month’s odyssey we survey the three castles of old Spiti and see what they can tell us about cultural links between this fringe region and the rest of the western Tibetan plateau. This article is the penultimate in a series on the cultural history and archaeology of pre-Buddhist Spiti. I hope you are enjoying exploring this fascinating land.

I would like to draw your attention to a recent publication of mine freely available online:

“The ancient corbelled buildings of Upper Tibet: Architectural attributes, environmental factors and religious meaning in a unique type of archaeological monument”, in “Architecture and Conservation: Tibet”, November 2015 (ed. Hubert Feigelsdorfer), pp. 4–19. Journal of Comparative Cultural Studies in Architecture. This special issue of the JCCSA is from the proceedings of the International Association of Tibetan Studies XIII, Ulan Bator. http://www.jccs-a.at/issues

The Ancient Castles of Spiti: The indigenous socioeconomic and cultural order and trans-regional communications in the era before the spread of Buddhism

Introduction to the ancient residential monuments of Spiti

This article describes the architecture and historical significance of ancient residential monuments in Spiti. There are just three ancient castles in all of Spiti and two of them clearly belong to the Tibetan Buddhist era (post-10th century CE), at least in their present configuration. Only one castle in the region possibly exhibits architectonic traits that signal an archaic cultural horizon (pre-10th century CE). No traces of pre-Buddhist temples or other major residential monuments were detected during the Spiti Antiquities Expedition (May-June 2015). I made extensive inquiries in an attempt to locate such sites but they do not seem to exist.

The lack of solid evidence for large residential structures in Spiti predating the 10th century CE is intriguing. In Ladakh but particularly in Upper Tibet, there are numerous castles, fortresses and temples belonging to the archaic era, which is comprised of the Iron Age (600–100 BCE), Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 600 CE) and Early Historic period (600–1000 CE).* On the average, in far western Tibet, a site consisting of elite residential monuments attributable to the archaic era occurs on the average every 500 km² or so. In Spiti, an area of approximately 7000 km², there is only one at most.

The most salient of architectural forms belonging to the archaic era in greater western Tibet is the all-stone corbelled edifice in various designs and aspects. For information, see my “The ancient corbelled buildings of Upper Tibet: Architectural attributes, environmental factors and religious meaning in a unique type of archaeological monument”, in Journal of Comparative Cultural Studies in Architecture (http://www.jccs-a.at/issues). For those wanting to know still more about archaic residential monuments in Upper Tibet and Ladakh, consult my various print publications (for bibliography, go to “Books” and “Articles” links on this website), as well as past issues of Flight of the Khyung.

In Upper Tibet an extensive network of strongholds and religious centers characterizes the archaic era. From these ancient installations it can be inferred that society was stratified with significant differences in wealth prestige and power distinguishing it. Some degree of occupational and possibly craft specialization is also indicated. Large permanent structures in Upper Tibet allude to the existence of a ruling and sacerdotal elite. The network of strongholds in Upper Tibet is in keeping with a political structure in which kings and/or chieftains with a considerable territorial remit grasped the levers of temporal power. Similarly, ancient religious centers indicate that a priestly class wielded considerable influence as well. Moreover, considerable human and material resources were required to undertake large construction projects, which points to a vibrant economic regime. Archaeological evidence from Upper Tibet shows that inter-regional trade supplemented subsistence activities such as stock rearing, farming and hunting.

The lack of archaic strongholds and temples on redoubtable terrain in Spiti strongly suggests that prior to the late 10th century CE this region was not as developed in a socioeconomic and political sense as its highland neighbors, Upper Tibet and Ladakh. Perhaps Spiti retained a tribal organization in which communal or republican structures dominated, rather than giving way to chieftains or kings with centralized control over large territories, economic resources and objects of social prestige.

What appears to be a society dominated by subsistence activities is reflected in the rock art record of Spiti. This rock art is characterized by indigenous styles of composition in which hunting and hunting-related activities are predominant. The relatively narrow purview of this art contrasts with Upper Tibet and especially Ladakh. The rock art records of these bigger neighbors convey contacts with foreign peoples, especially those of Central Asian origins. Communications with other Eurasian lands that had well-developed Bronze Age and Iron Age legacies facilitated the establishment of relatively advanced socioeconomic and technological regimes in Ladakh and in Upper Tibet.

While large monuments appear all but unknown in archaic era Spiti, more modest residential structures may well have been part of the architectural picture. Clearly, agriculture was established in Spiti prior the 10th century CE. It was a prerequisite for the founding of Buddhist monasteries in the region (such as La-ri and Ta-po), circa 1000 CE. These were built amid settled areas forming the nuclei of a new socioeconomic order. Thus, it appears that the residential infrastructure of early Spiti consisted of agricultural villages with households as the basic unit of habitation. Findings from western Tibet demonstrate that agriculture was well developed in the Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 600 CE), but its origins probably predate that time (precisely when remains to be determined; on this subject, see February 2015 Flight of the Khyung).

Given the great utility of agriculture, the cultural and geographic proximity of Spiti to Upper Tibet and Ladakh, and the region’s ample arable lands, farming may have been practiced in Spiti even before to the Early Historic period (perhaps as early as the Iron Age). The most persuasive piece of evidence supporting this perspective is that most ancient tombs in Spiti are situated on the old peripheries of villages. Now, with rapid expansion due to modern economic and political forces, villages are increasingly encroaching upon pre-Buddhist cemeteries. The fact that burials are consistently found at the traditional delimits of villages suggests that these loci of settlements were already established, the cemeteries accommodating pre-existing patterns of habitation (more on this subject in next month’s Flight of the Khyung).

The probable existence of archaic era settlements in the same locations as contemporary villages in Spiti is not surprising. There is considerable archaeological and historical evidence to show that certain villages in agrarian Ladakh, Upper Tibet and Central Tibet have deep historical legacies. The continual redevelopment of habitations over long periods of time frequently occurs at prime places (sites with water, arable land, arterial routes, defensive endowments, etc.).

An agrarian way of life requires fixed facilities for the housing of grain and other produce, agricultural implements, and stock used in plowing, transport and threshing. This sheltering function is often fulfilled by the creation of permanent or semi-permanent domiciles. These can range from rudimentary huts of hide, brush and thatch to substantial multi-storied masonry buildings (like those prevailing in Spiti over the last millennium). As archaeological excavations have not been conducted in Spiti, it is not yet known what archaic abodes in the region may have looked like.

Gyadrong

One of the only ancient residential sites still visible in Spiti is called Gyadrong (brGya-grong; Village of a Hundred Houses; 3260 m el.). Gyadrong is located on the edge of a bluff overlooking a stream issuing from a gorge, just west of the village of Lari (La-ri). According to local elders, Gyadrong was the original settlement in Lari, which was destroyed long before living memory. It was replaced by another village to the northeast, which itself was abandoned about 70 years ago. It is reported that an avalanche threatened this second village of Lari, forcing the inhabitants to relocate. The contemporary village is more sprawling than the village in which the oldest residents of Lari were born.

As the name suggests, it is believed that Gyadrong once had a hundred houses. It has been reduced to a dense dispersion of stones covering an area of at least 7000 m². The structures that once existed at this site are now completely disintegrated, precluding an appraisal of its architectural character from a visual survey alone.

Fig. 1. The bluff upon which Gyadrong sits.

Fig. 2. A view of Gyadrong and the bluff from the north.

Fig. 3. The Gyadrong dispersion.

Fig. 4. The ruins of Gyadrong, which are so degraded that individual structures can not be differentiated from one another. This site may hold great promise for further archaeological investigation.

What must be a reference to Gyadrong but under an alternative name was made by A. H. Francke a little more than a century ago.* Francke called this ruined settlement Serlang and described it as an “ancient castle”, the former abode of the inhabitants of Lari. According to Francke, Serlang, an extensive settlement, was located above Lari on the side next to a brook. This rather ambiguous description of the location misled the Indian studies specialist H. Taucher to conclude that no traces of it have survived,† when in fact there are still large in situ ruins. Tauscher’s belief that Lari may have once been the most important settlement in lower Spiti is given some credence by the presence of these ruins. A Buddhist temple is recorded in the old biography of Lotswa Rinchen Sangpo (composed by his disciple Ye-shes dpal) as having been established in Lari circa 1000 CE. Its whereabouts are still not clear, suggesting perhaps that it was wiped out in a landslide.

See Francke, A. H. 1914: Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Part 1, Personal Narrative, p. 35. Reprint, Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, New Imperial Series, vol. 38., S. Chand, 1994.

See p. 228, Tauscher, H. 1999: “Here in La Ri, In the Valley Where the Ten Virtues Convene… A Poem Dedication in the “Tabo Kanjur””, in Tabo Studies II. Manuscripts, Texts, Inscriptions, and the Arts (eds. C. A. Scherrer-Schaub and E. Steinkellner), pp. 227–241. Serie Orientale Roma LXXXVII. IsMEO: Rome.

Dankhar

The best known of Spiti’s so-called castles is Dankhar (Brang-mkhar; 3930 m el.), once the headquarters of the Nono or native rulers of the region. Dankhar is situated on a rocky spur some 400 m above the Spiti valley. It overlooks the eponymous village, the spur forming one half of an amphitheater in which much of the current village of Dankhar is located. The east half of the same line of crags is the site of Dankhar monastery. In the west half of these crags is the Nono’s old residence, an amalgamation of structures built at different times. This site is known as Khartö (mKhar-stod). Although there are well preserved buildings from the 19th and early 20th centuries incorporated into the residential complex of the Nono (ruler of Spiti), there is limited evidence for a fortified installation at Khartö.

Fig. 5. Dankhar. The monastery is in the crags on the left and the old residential complex of the Nono is higher up in the crags to the right.

Fig. 6. Khartö, the residential complex of the Nono at Dankhar. The most recent residence of the Nono is in the right half of the image. The new road in the foreground links Dankhar with the village of Lhalung.

In a trip to Spiti taken in 1863, Philip Henry Egerton, the Deputy Commissioner of Kangra, describes the Nono’s residence (he calls it “Dhunkur”) as only “an ordinary house of rather larger dimensions than usual”.* This general impression of the modest nature of the site is echoed by A. F. P. Harcourt, Assistant Commissioner for the Punjab, writing in the 1870s.† He described the Dankhar castle as a collection of houses joined together on a promontory. Harcourt adds that he detected no signs of a fortress or defensive structures.

See Egerton, P. H. 1864. Journal of a Tour Through Spiti to the Frontier of Chinese Thibet, p. 44. Reprint, Bath: Pagoda Tree Press, 2011. For a photograph of Dankhar taken at that time, see ibid., p. 53 (pl. 23). For excellent reproductions of photographs of Dankhar taken in the 1870s for the Firth Catalogue, see Rayner, H. A. 2013: Firth’s ‘Universal’ India Series. Views in Kulu and Spiti, pp. 36–40. Bath: Pagoda Tree Press.

See Harcourt, A. F. P. 1871. The Himalayan Districts of Kooloo, Lahoul and Spiti, pp. 102, 103. Reprint, Delhi: Vivek Publishing House, 1972.

The young British explorer George Trebeck visited Dankhar in 1821. He describes the fort as an irregular narrow figure of the same essential form and strength as a common house. Trebeck adds that it included a small enclosure with loopholes.* In the edition I have of his book (coauthored with William Moorcraft) there is a print of Dankhar on the frontispiece, although there is no caption accompanying this black and white line drawing. When it is compared to photographs of Dankhar shot in the 1860s and 1870s, it can be seen that the castle had become reduced in size. The invasion of the Sikhs and Dogras in the 1830s and 1840s may possibly account for its structural diminution.

Moorcraft, W. and Trebeck, G. 1841. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Panjab; in Ladakh and Kashmir; Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara, p. 59. Reprint, New Dehli: Asian Educational Services.

In the oldest standing part of the Nono’s residence there is a lhatho (lha-tho), a shrine primarily used in the worship of territorial and ancestral deities. It is comprised of stone, mud brick and rammed earth walls and appears to predate the 19th century. East of the Nono’s residential complex is an older portion of Kharthö. The structures there exhibit the same three basic types of wall fabrics as the more recent residences at Khartö. Some of these east sector remains appear to be centuries old. Near the older ruins is an intact structure, a former domicile now used for storage. One of its entranceways is only 1.2 m in height, a traditional architectural feature that persisted through the 19th century in Spiti (see June 2015 Flight of the Khyung).

Fig. 7. Structures around the lhatho shrine (the base of which is visible). This appears to be the oldest standing part of the old royal residence at Dankhar. It is likely to predate the 19th century complex to which it is appended.

Fig. 8. What appears to be the most modern structure (right side of image) of the royal residential complex at Dankhar, probably dating to the early 20th century.

Fig. 9. A former residence of stone and mud brick at Khartö now used for storage. Note the tiny entranceway. This is one of the oldest intact houses left in Spiti. It should be earmarked for preservation.

Fig. 10. A stone foundation of unknown age and function at Khartö.

Fig. 11. Walls (rammed earth, mud brick and stone types) embedded in the formation at Khartö. These appear to be among the earliest structural remains at the site. The massiveness of the walls and their integration into the crags suggests that they were part of a stronghold.

According to Thukral (2006), Dankhar once housed the royal family, the courts, community grain stores and a dungeon.* Thukral suggests that the Nono relocated to the village of Kyuling (Kyu-gling) on the Spiti valley floor as early as 200 or 300 year ago. This may have been the case, but residential facilities were maintained at the ancestral headquarters of Dankhar into the 20th century. The death of the Nono in 1864 and the British stripping his successor of many of his traditional powers† may have contributed to the decline of Dankhar as a royal seat of power.

See Thukral, K. 2006: Spiti: Through Lore and Legend , p. 22. New Delhi: Mosaic Books.

On this historical episode, see Kapadia, H. 1999: Spiti: Adventures in the trans-Himalaya, pp. 35–40. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company.

It is not known when Dankhar was founded but it may have been in the same period as the foundation of the eponymous monastery (cf. Thukral: 25). This scenario is strengthened by an account in the Tibetan historical text mNga’ ris rgyal rabs, which suggests that the site (called Seng-brag (sic) brang-mkhar) was occupied by Guge royalty at the end of the 11th century CE.* Laurent (2011: 125, 126) believes that the monastery is the vestiges of a royal residence. I am not so sure though because what he calls “large defensive stone walls at ground level” seem to be revetments commonly used in Tibetan monastic constructions emplaced on difficult terrain. I think it is more likely that the ancient royal residence and monastery were always separate complexes, the former being the Khartö site, which is clearly an elite residential installation.† Any elite residences at the monastic complex are more likely to have been abbatial in nature.

See Vitali, R. 1996: The Kingdoms of Gu.ge Pu.hrang. According to mNga’.ris rgyal.rabs by Gu.ge mkhan.chen Ngag.dbang grags.pa, pp. 125, 344. Dharamsala: Tho.ling gtsug.lag.khang lo.gcig.stong ’khor.ba’i rjes.dran.mdzad sgo’i go.sgrig tshogs.chung. Also see Laurent, L. N. 2010. “The fortress-monastery of Brag mkhar: An anamnesis” in The Ancient Monastery Complex at Dangkhar. Research and Restoration Project – Annual Report 2010, pp. 7–14. Graz: Graz University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture, Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies. This work reviews the historical, cultural and religious background of Dankhar.

http://savedangkhar.tugraz.at/pdfs/2010/the%20fortress-monastery%20of%20brag%20mkhar.pdf

In his pioneering work at Dankhar, Laurent (2011: 125) translates mkhar-stod as “upper part of the fortress” but this is not the ideal gloss for the term. It is much better rendered as ‘the elevated castle’ or ‘the exalted castle’, denoting its uppermost geographic position but also with connotations of ‘superior’ and ‘foremost’. This definition is corroborated by folksongs of Spiti and by customary usage of the term in Tibetan toponymy. See Laurent, L. N. 2011” “More Historical Research on Brag Mkhar”, in The Ancient Monastery Complex at Dangkhar. Research and Restoration Project – Annual Report 2011, pp. 124–136. Graz: Graz University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture, Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies.

http://www.savedangkhar.tugraz.at/pdfs/2011/07_more%20historical%20research_hp.pdf

Kharteng

The ruined stronghold of Kharteng (mKhar-steng; 3700 m el.) or ‘The Castle Above’ is situated on a hilltop that rises above the village of the same name. In the middle of this site is a lhatho shrine and small chapel dedicated to the local territorial deity (yul-lha) Tsebla (rTse-bla), the most important indigenous spirit of the Pin (sPin/sPrin) valley.*

For more on this deity and the castle, see June 2015 Flight of the Khyung, figs. 2, 3.

Unfortunately, most of the history of Khar has been lost to be replaced by legend, as is the case with so many ancient sites the world over. It is thought that fifty primary households (khang-chen) founded Khar, but it was later neglected after the population grew large and dispersed to found other settlements in the Pin valley. It is said that a series of smoke signals on high ground would alert the defenders of Khar to the advance of invaders from Kinnaur and other parts of Spiti. At those times the entire local population is supposed to have sought refuge in the castle. The age of Kharteng is not known except to state that it belongs to the historical epoch. Local luminaries opine that it may be 600 or 700 years old (it is believed to predate the Buddhist monastery in nearby dGung-ri), but this is still to be confirmed.

Fig. 12. The northeast side of the hill at Kharteng. Note the lhatho shrine and chapel on the summit and the rubble strewn slopes below.

Fig. 13. The traces of structures on the summit of Kharteng looking north. The sheer drop on the southwest side of the hill is seen on the left side of the photograph.

Fig. 14. The summit of Kharteng (looking south). Note the retaining wall on the southwest (right) side of the hill. In the background is the lhatho shrine and chapel.

The shark’s tooth-like hill on which Kharteng was established is inherently defensible, suggesting that it did indeed function as a redoubt. There are no intact superstructures at Kharteng, making it very difficult to appraise its architectonic qualities. Wall footings of buildings exist in a few places but they are obscured by rubble. The southwest side of the hill is natural limestone precipice. There are bits of revetment along the rim on this side that may have been connected to a parapet wall. Much rubble pours down the sloping northeast flank of the hill. The length of the dispersion at Kharteng, paralleling the axis of the hill (northwest-southeast), is 83 m. The hilltop is only 8.5 m wide on its south side and 17 m wide on its north side.

Fig. 15. The lhatho shrine and rammed earth wall fragment forming the southeast extremity of Kharteng.

Kharteng was built of limestone blocks, most of which were unhewn and rammed earth walls. A rammed earth wall fragment bounding the southeast side of the installation is a maximum of 4.2 m in height. The rammed earth wall extends all the way down to ground level in places, while in other sections it rests upon a stone base up to 1.5 m in height.

Fig. 16. A view of the tunnel on the northeast slopes of Kharteng.

The most intriguing structural feature of Kharteng is located on the northeast slopes of the hill. Here there are traces of a tunnel that the zigzags up the hill for approximately 35 m before disappearing underground. This tunnel has stone walls and a roof composed of heavy stone members laid directly on top of the walls. The tunnel appears to around 85 cm wide and at least 1.1 m tall but much of it is now in-filled with earth and rubble. According to the local oral tradition, this tunnel originally extended from the base of the hill to the summit and was used to access a water supply during times of a siege. This account, however, must be questioned because the tunnel seems to open up onto a wide expanse that would have been very difficult to defend or keep secret.

Kharnya

What appears to be the largest and oldest fortress in Spiti is called Kharnya (mKhar-gnya’; Neck Castle; 3520 m el.), so named for its position on the ‘neck’ of a mountain. It is also called Kharnyak (mKhar-nyag; spelling and meaning uncertain). Ironically, Kharnya is the least known of the three ancient strongholds in Spiti. Few natives outside the immediate area are even aware its existence. A number of luminaries I spoke with were surprised to learn about Kharnya. This lapse in the cultural consciousness of Spiti is reflected in the site itself, which hosts a very minimal array of Buddhist monuments, in contrast to Dankhar and Kharteng with their conspicuous signs of this religious tradition.

Fig. 17. The ruins of Kharnya can be seen on the summit of the hill in the middle of the photograph. The village of Nakthang is in the foreground.

Kharnya is poised on the top of a conical hill that commands excellent views of the Spiti valley from Poh (sPo) upstream to Kyur (sp.?) downstream. The castle rises 140 m above the village of Nakthang (Nags-thang; Forest Plain). The village is so named because it is thought to have been surrounded by a juniper forest, but almost all traces of it have been extirpated. The village is also called Nethang (gNas-thang; Sacred Place Plain), but this seems to be a more recent appellation reflecting Buddhist values.

According to the traditional doctor (E-mchi) of nearby Poh (sPo) village, the leader of Kharnya was a woman named Jomo Chokpa Kyi (Jo-mo lcog-pa skyid). Alternatively, two elderly women of Nakthang told me that Kharnya was built long ago by three rich men from the village.

A folktale preserved by the village priest (jo-wa) of Nakthang, Lobsang Phuntshok (Blo-bzang phun-tshogs), and other local elders, tells of a king who ruled from Kharnya. This proud and impetuous monarch was displeased because he thought that his castle did not receive enough sunlight. He ordered his subjects to cut down the tall mountain to the east of the castle in order to admit more light, but this proved an impossible task. After undergoing many hardships trying to do the bidding of their king, the subjects had had enough but they were not sure what to do. Many deliberations ensued but nothing could be decided until a young woman with a baby on her back got up before the assembly of villagers and began to sing and dance. She sang that it was better to cut the king than cut the mountain. The implications of her words had a powerful effect on the assembly, leading to the assassination of the king of Kharnya.*

A very similar tale is told about a fortress in Guge called Thönlo Khar (mThon-lo mkhar). See my 2014: Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: A Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites on the Tibetan Upland, Residential Monuments, vol. 1, p. 63. Miscellaneous Series – 28. Sarnath: Central University of Tibetan Studies. Online version: Tibetan & Himalayan Library (THlib.org): http://www.thlib.org/bellezza, 2011. The folktales around Kharnya and Thönlo Khar are essentially a metaphor, with the effect of reducing the historical significance of these sites. The factors behind this denigration are unclear.

Fig. 18. The outer north wall of the Kharnya installation. This wall stretches for almost 44 m.

Fig. 19. A close-up of the outer north wall, Kharnya.

Fig. 20. The outer south and west walls of Kharnya.

Fig. 21. A highly eroded rammed earth fragment in the outer north wall, Kharnya.

The lofty aspect and steep surrounding terrain of Kharnya confers a defensible mantle upon the site. However, there are no signs of ramparts or other defensive structures around the complex. The ruins of Kharnya form a compact mass measuring 43.5 m (east-west) by 10. 2 m (east side) to 21.5 m (west side). This complex housed 25 different rooms, the partitions of which are still partially intact. The uniformity of the constructions and ground plan of Kharnya indicate that it was built as an integral installation. There is no obvious evidence for reconstruction or subsequent modification of the site.

The walls of Kharnya are primarily composed of a random-rubble fabric, 40–50 cm in thickness, except the rear (south) outer wall of the castle, which is around 60 cm thick. Stones of variable length (10 cm to 1 m) were used in construction. There is also a tiny rammed earth wall fragment (80 cm x 60 cm x 20 cm) sitting on top of the outer north wall of the installation. This rammed earth wall is highly eroded. All walls of Kharnya have been reduced to 3 m or less in height. The wall construction and ground plan of the facility indicate that the structures had roofs supported by timbers. There are no niches in any of the walls.

The ground plan of Kharnya consists of two parallel rows of rooms on the north (lower) and south (upper) sides of the complex. There are 11 rooms in each of the two rows, which are set at a distance of 4 m from each other. There is a 5 m difference in elevation between the north and south rows of rooms. Each of the rooms measures between 2.3–3.6 m and 3.4–4.5 m. The north row is divided into two separate parts by the main entrance to the castle situated in the outer north wall. This entrance is 2.6 m wide and an inlet formed from parallel walls running perpendicular to it is 3.6 m long. There appears to be a gap in the upper row of rooms, suggesting that it was comprised of two different buildings as well. In addition to the axial arrangement of the 22 rooms, there are three more rooms on the west side of the complex. At the southwest corner of the complex is a small prayer flag mast (dar-lcog) and lhatho cairn.

Fig. 22. A view from the east of the lower row of rooms at Kharnya . Various room partitions are visible in the photo.

Fig. 23. The lower row of rooms as seen from the west, Kharnya.

Fig. 24. A view of some of the lower (north) and upper (south) structures at Kharnya.

Fig. 25. A view of the upper row of rooms, Kharnya.

Fig. 26. The outer south wall and upper portion of Kharnya.

Fig. 27. The grand entranceway, Kharnya.

Fig. 28. The modest lhatho and prayer flag mast near the southwest corner of the Kharnya complex.

The size and configuration of structures at the other two castles of Spiti, Dankhar and Kharteng, were more constrained by the local topographic conditions than was Kharnya. Kharnya is also the only one of the three strongholds to be built near the Spiti river. The other two sites are much further removed from this major artery of communications, as if they were established in a different social and strategic environment than Kharnya. The history of Kharnya is a mystery. Who built is and when are questions for which there are still no answers. There is no mention of Kharnya by that name in the old biography of Lotswa Rinchen Sangpo, but perhaps it is noted somewhere else in the vast literature of Tibet.

The size of the Kharnya complex, its adeptly built stone walls, commodious rooms, wide entranceway, and geographical aspect are construction and design traits indicative of an elite monument. Significant levels of economic resources and social organization were required in order to create such a castle. The exclusive nature of the site is heightened by its uniqueness in Spiti. It can be inferred from the ground plan of Kharnya and its multiple rooms that it was designed to accommodate significant numbers of people. Division into many rooms suggests that the occupants of the facility formed various subgroups. These subgroups could have been distinguished from one another by occupational specialization, genealogical affiliation or perhaps in other ways too. There is no particularly large or elaborate structure at Kharnya that could be identified as being associated with its head. Nonetheless, the relative social status of residents may have been determined by the number of rooms they occupied.

The absence of dedicated defensive features at Kharnya suggest that it functioned as a palace and/or administrative center rather than a fortress per se. Kharnya, the only hilltop installation in lower Spiti, would have controlled access along the Spiti river, regulating traffic between the major villages of Poh and Tabo. The hazy collective memory around Kharnya and its marginal role in the ceremonial life of Spitians suggests that it may not have a Buddhist identity. This impression is strengthened by the architecture of the site: there is no structural evidence for a Buddhist temple or any other centralized space at Kharnya. The axiality of the installation is strictly adhered to with the exception of the addition of three rooms in a west wing.

The size, style and location of Kharnya, as well as social neglect and the peculiar folktales surrounding it of a female ruler and an evil king, seem to point to a cultural context at variance with the Tibetan Buddhist era of the last millennium. Structural affinities with ancient strongholds in Upper Tibet reinforce this assessment of the site.* Provisionally, therefore, I will put forward that Kharnya might have been founded prior to 1000 CE. If this appraisal is proven valid, the site is attributable to the archaic era in Spiti’s cultural development; that is, one that belonged to a pre-Buddhist regime.

The geographic aspect and axial plan of Kharnya are reminiscent of Mani Thangkhar (Ma-ṇi thang-mkhar), a castle in the Guge village of Nu (sNu; see Bellezza 2014, pp. 218–221). In local folklore, Mani Thangkhar is associated with an ancient tribe known as the Mon.

Next Month: Documenting the opening of ancient tombs in Spiti and the search for the missing artifacts!