October 2012

John Vincent Bellezza

This month’s Flight of the Khyung takes in a wonderful range of antiquities documented in 2000 and also in 2011. It relays the challenges of being on expedition at the turn of the millennium, a journey that helped recast the archaeology of Upper Tibet. Additionally, there are pieces on the people and religious lore of western Tibet. Hope you enjoy it all!

If you have any suggestions about subjects you would like to see covered in future issues, please contact me at jbellezza@hotmail.com.

More felines of ancient Tibet

To complement the August newsletter on tigers, two more ancient felines are presented for your inspection, one from the rock art record and one from a collection of amulets for sale in Lhasa.

Fig. 1. Feline pouncing upon a stag, northwestern Tibet, probably protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE). Documented in 2011.

The long curled tail overarching the back of this sleek animal quite securely identifies it as feline in character. As we saw last month, many such cats can be identified as tigers. Perhaps lions are also represented in the prehistoric rock art of Upper Tibet but this remains to be confirmed (the lion is found in historic era engravings of western Tibet). The other great cat of the region is the snow leopard. Lesser cats such as the Eurasian lynx are not powerful enough to take down a fully grown stag (not to mention that they have a stubby tail). While the feline lunges at its prey, the stag (identified through its branched horns) appears to be rearing up in fright.

Fig. 2. Felines with a similar style tail rising over the body and thickly curled at the end are known from thokcha (thog-lcags) resources. The pictured amulet also has a body shaped like the rock art example. This copper alloy object dates either to a latter phase of the protohistoric period or to the early historic period (650–1000 CE).

In the absence of archaeologically dated specimens it is hard to be more specific about the age of this thokcha. As with comparisons drawn in previous newsletters, we can readily see how the esthetic development of rock art and artifacts ran in parallel, these disparate media informing the conceptual basis of one another. This artistic cross-fertilization is liable to have been active for many centuries terminating in the early historic period, which coincided with a steep decline (quantitatively and qualitatively) in rock art production. As most thokchas are devoid of a secure geographic context, rock art constitutes one of the best means we have for ascribing them with a Tibetan provenance. Other artistic media such as sculptures and paintings also help confer a Tibetan identity on thokchas.

Archaic residential sites surveyed in 2000

In 2000, I embarked on the Upper Tibetan Antiquities Expedition (UTAE) with the aim of documenting more pre-Buddhist archaeological sites on the Changthang and in the valley systems of far western Tibet. In this issue we examine a few of the residential sites discovered on that expedition. These sites have been published (with black and white photographs) in my book Antiquities of Upper Tibet (Adroit Publishers: Delhi: 2002), but it is only by highlighting them on the internet that they reach a wider audience. The photos shown here were all taken on the UTRAE. Other images of these places have not yet been digitized. A project to do so is of course welcome.

Fig. 3. A partial view of Sharo Mondur. The ruins are spread across the middle of the photograph.

Sharo Mondur (Sha-ro mon-dur, Rotten Flesh Mon Tombs?) sits atop a small plateau located above the rich pasturelands of Pangngar Zhung (Spang-ngar gzhung), in the western Changthang. This sprawling complex is thought to have been built and inhabited by an ancient people known as Mon. Supporting its archaic cultural status is the fact that there are is Buddhists art or emblems at this location as well as its altitudinous aspect (situated at 4700 m or 300 m above the river valley). Traces of large structures at Sharo Mondur demonstrate that it was an important ancient center. Nowadays the site is completely abandoned. It is possible that rather than a residential site Sharo Mondur represents a large necropolis. In any case, the lack of revetments, ramparts, curtain-walls and other defensive features illustrates that it was not designed as a fortress.

The fairly dense agglomeration of ruined structures at Sharo Mondur covers an area measuring 135 m (north to south) by a maximum of 70 m (east to west). There are also some outlying ruins. The structures are comprised of substantial limestone foundations and scattered wall segments up to 1.5 m in height and 1 m in thickness. Inside some of the structures there is evidence of significant excavation, which seems to have occurred well in the past. This may hint at the widespread looting of the site.

As the remains of Sharo Mondur are in an advanced state of disintegration, little can be said about the ground plan and character of what was obviously a large monumental presence. Most of the structures are quadrangular in shape and appear to be the footings of buildings. Some of the ruins seem circular and resemble ‘Mon’ tomb typologies. Now that I have more experience and information, it would be good to revisit Sharo Mondur and survey this intriguing site in greater detail.

Fig. 4. Upper tier rooms of Structure VI, Dzong Karpo, the western Changthang.

Dzong Karpo (Rdzong dkar-po, White Fortress) is situated at the head of a long valley in the western Changthang. Once a significant residential installation, this 5100 m high site has been utterly abandoned. A gigantic red and white limestone outcrop shelters seven or eight ruined edifices. These all-stone corbelled structures were built into cliffs and outcrops. It is believed by local sources that the remains of Dzong Karpo remains represent a religious center constructed by the ancient Mon, a tribe or people of enigmatic origins. The architectonic character of the ruins and their identification with the Mon indicates that this is an archaic cultural facility. However, the presence of a clockwise swastika sculpted on a hearth in one of the upper rooms of Structure VI demonstrates that the complex was utilized subsequently by Buddhist practitioners.

Most of the structures at Dzong Karpo were multi-roomed affairs, indicating that this site may have once accommodated dozens of individuals. The single largest edifice is Structure VI, which stands at the base of a huge limestone cliff. This two-tiered edifice has a maximum length of 16 m. The upper and lower levels of this building are separated by 2 m high walls built against the escarpment. One room (2 m x 1.8 m) in the west section of the lower tier Structure VI has its stone roof partially intact. Bridging stones bearing down on corbels span the outer masonry wall and the cliff face. The stone sheathing laid on top of these stone members is partially in situ.

There were probably a total of six rooms in the upper tier of Structure VI. Two commodious upper tier rear rooms, with their fairly elaborate stone appointments, relatively high entranceways and ceilings, and location at the uppermost part of the site, appear to have had special importance, perhaps as the ritual or temporal center of Dzong Karpo. In one of these rooms, the jambs, lintel and threshold stone of the doorway (1.3 m x .5 m) are still preserved. Inside this room there is a stone and adobe hearth decorated with a parget clockwise spiral design known as yungdrung kyilkhor (g.yung-drung dkyi- ’khor) and a conjoined sun and moon (nyi-zla). Other interior features include stone shelving, two niches in the rear wall, and a floor-to-ceiling rounded alcove 65 cm in width. The other largely intact rear room (3.3 m x 4 m) has an independent entrance. Inside there is a stone table supported on stone legs standing in front of a recess in the cliff. Much of the roof has survived in this room: long bridging stones stretch between the cliff and outer wall and support stone sheathing.

Fig. 5. The upper and middle levels of Tsaktik, western Changthang.

The history and folklore surrounding the residential structure of Tsaktik (Btsag-tig) seems to have been lost by regional elders. The structure was built into a rocky bluff overlooking a small river. Tsaktik is far removed from contemporary permanent settlement. No Buddhist symbols are found at the site and it appears to have an archaic cultural status.

The single building at Tsaktik is 14 m long and consisted of at least seven small rooms split between three levels. The trunks of tamarisk (’om-bu) used in the construction of its lintels and roof are larger in girth than those still growing in nearby relict groves of the species. These wooden appurtenances could potentially be radiocarbon dated. Constructed of limestone, the walls of the two lower rooms and the walls of the two outer rooms of the middle level are highly fragmentary. The two inner rooms of the middle level however are in significantly better condition. The most intact room has much of its gravel, clay and tamarisk roof intact, and mud plaster still clings to the walls. In this room (2.5 m x 3 m) beams of tamarisk span the cliff and outer masonry wall. Inside there is a stone platform and a niche with a tamarisk lintel. Although the walls and ceiling are fire-blackened, nothing endures of the hearth. An interconnected (by way of a small portal), similarly sized room has a tamarisk lintel over an opening in the outer wall. The exterior wall is also bonded with tamarisk. There are the remains of a stone platform in this room as well. The upper level of Tsaktik consists of a ruined room on the rim of the bluff and the remains of a parapet wall that enclosed the facility.

Fig. 6. The largest ancient structure at Gurgyam

The ancient site of Gurgyam (Gur-gyam, sometimes also called Gu-ru gyam) is situated on the esplanade above an eponymous escarpment, in the upper Sutlej (Glan-chen) River valley. This well known site has more than two dozen caves, most of which are no longer inhabited. A nunnery founded by the renowned Bonpo lama Khyungtrul Rinpoche approximately 75 years ago, in the east part of the escarpment, still lies in ruins. The main hermitage is called Yungdrung Rinchen Barwai Druphuk (G.yung-drung rin-chen ’bar-ba’i sgrub-phug (Meditation Cave of the Blazing Jewel Swastika). According to the monks of Gurgyam, this cliff shelter enshrines the cave that was used by the renowned Zhang Zhung saint Drenpa Namkha (Dran-pa Nam-mkha’); however, no structural features from this early period are extant.

According to the Bonpo monks, the ancient residential ruins on the esplanade probably date to the time of the Zhang Zhung kingdom, but this could not be independently confirmed. The largest structure measures 11.5 m (east to west) by 16 m (north to south), and is partitioned into as many as ten rooms. The walls of the hulk have been reduced to 1.7 m in height. The exterior of the structure is elevated about 3 m above the surrounding ground level by a massive but crumbling revetment. There are also two smaller and even more poorly preserved structures in the vicinity.

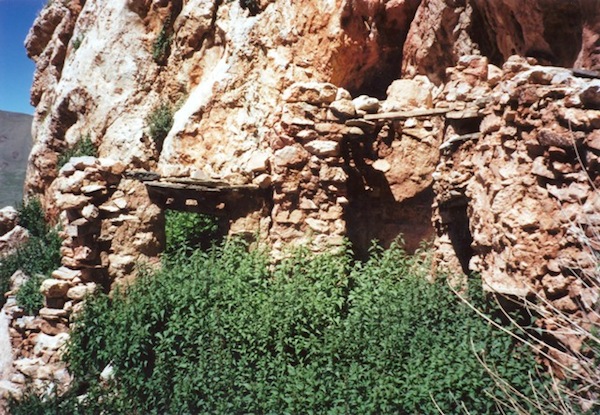

Fig. 7. The largest building ensconced in a deep overhang at Sheldra.

Sheldra (Shel-’dra, Crystal Likeness) is one of the best known hermitages at Kang Rinpoche (Gangs rin-po-che). It is located up valley from Selung monastery at 5300 m elevation. Sheldra has been used by Buddhists meditators for centuries and was partially restored in the aftermath of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. However, it is no longer occupied on a regular basis. No local information on the history of the site was forthcoming. Given the wealth of archaic sites built in the same style and occupying the same general setting in the area, it seems likely that Sheldra originated during the archaic cultural horizon.

Spanning 14 m of the cliff face, the modern construction has incorporated structures of an ancient pedigree. These older habitations include two rooms built into an overhang in the cliff on the south side of the historic era hermitage. On the north side of the retreat there are three small rooms, two of which still have fully intact all-stone corbelled roofs. Also clinging to the cliff, southwest of the modern hermitage, are the remains of five small cells stretching for 12 m. Each of these cells could only have accommodated one inmate.

A little further west is another complex built into a deep overhang in the Sheldra escarpment, effectively protecting the site from rock falls. It consists of two smaller structures, as well as a larger, relatively well preserved example. The larger building (4.5 m x 9 m) contains five rooms. The two central rooms still have intact all-stone corbelled roofs and the north room an incomplete stone roof. The roof over these rooms was built in the manner typical of ancient Upper Tibet: stone slabs were laid on top of bridging stones that bear down upon corbels. The three better preserved rooms form a wing with a separate exterior entrance and considerably smaller internal entrances between rooms. Inside the largest room (2.6 m x 2 m) there are the remains of a fireplace as well as stone niches and shelving. In the outer wall of the largest room there are two small openings to admit light.

Fig. 8. The three-story façade and cave of Drak Khorgang.

Drak Khorgang (Brag ’khor-sgang, Circle Hill-Spur Rock) is an ancient cave shelter of which little or nothing appears to be known. It is located in the western Changthang. Evidence for an early foundation date includes:

- Unusual three-tiered aspect of the façade

- Apparently no Buddhist historical associations or symbolism connected to the site

- Herringbone courses of masonry in the façade, not unlike those found in the mortuary temples accompanying arrays of pillars

The façade of the cave is more than 10 m tall, creating three levels. The walls of this well-built, west-facing structure have undergone much deterioration. It appears that steps led up to the entrance and from there higher up to a landing. The second level of the cave is the largest (4.5 m x 3.5 m) and is covered in thick deposits of bird droppings. Surrounding the upper level of the cave is elaborate stonework that is now highly fractional.

Selected journal excerpts from the Upper Tibetan Antiquities Expedition

September 7, 2000: elders of Mount Kailash

I had quite an extraordinary day, thank you. On my way past Darchen Gonpa (Dar-chen dgon-pa), which is in a much neglected state these days [now it its completely ruined], I met one of its local associates, Tshering Dorje of the Chakpa (Phyag-pa) clan. He was born in the Year of the Pig, 1923 [Tshering Dorje passed away a few years ago]. For a price, this gentleman agreed to guide me to a couple of ancient ‘Bon’ ruins in the area. The old codger plied me for as much as could he get, but I could not really begrudge him. The older generation of Tibetans possesses a dignity and strength not often found in the younger generation, which has grown up in a much different world. Anyhow, I was impressed by Tshering Dorje’s vitality. He moved like a man many decades younger in age. Tshering Dorje made over 100 rounds of Mount Tise in various years of the snake, in addition to dozens of circuits (skor-ba) in alternate years. Even this year, aged 77, he is going around Mount Kailash; 50 km in one day! No doubt, the blessings accrued from having made so many circumambulations accounts in part for his tremendous stamina. He has also made numerous rounds of Tsho Mapham. Two more prodigious walkers around the sacred mountain and lake are Konchok (aged 78), the lama of Choku Gonpa (Chos-sku dgon-pa) and his wife (aged 71). Like Tshering Dorje, they too are Kangriwa (Gangs-ri-ba) or natives of Mount Kailash.

September 2, 2000: a religious ghost

Approximately 1 km north of the Gunsa (Dgun-sa) township headquarters is a large ochre tinted boulder called Takribuk (Stag-ri sbug, Tiger Mountain Nook), a shrine for the well-known protector of Gar (Sgar), Taklhamembar (Stag-lha me-’bar). In the center of the site there used to be a small Lamaist retreat but it did not survive the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Every month on the third lunar day the Ngari viceroy (Mnga’-ris sgar-dpon) or his representatives would come to Takribuk to hold a lhasol (lha-gsol; ritual of propitiation) in honor of the deity. Military functionaries known as the twenty-five Sokmak (Sog-dmag; originally a group of military leaders under the 17th century general, Dga’-ldan tshe-dbang) also participated in the appeasement of Taklhamembar. On the third day of the twelfth month they were joined by one member of each household residing in Gar. The Dzamling Chisang (’Dzam-gling spyi-bsangs) festival was also celebrated locally at Takribuk.

Taklhamembar (also spelled Stag-la me-’bar) is the name of a Bon protective deity thought to have originated in Zhang Zhung as well as the name of a Zhang Zhung period adept. The Ngari viceroy, however, worshipped a bastardized form of the deity with a spurious theogony. Why did Tibetans resort to worshipping ghosts when they had such a noble and hoary lineage of bona fide protective spirits? [It appears that the Bon deity was transmogrified into a vengeful ghost, as per Tibetan Buddhist practice, but this is a subject requiring further research].

The following tale is told [by local elders] about the creation of Taklhamembar, an example of ‘a man dies, a tsen is born’ (mi-shis btsan-skyes) phenomenon common in the Dewa Zhung (Bde-ba gzhung) period (circa 1670–1959). Two or more centuries ago, Khampa bandits roamed around Ngari causing significant loss of life and property. A particularly powerful gang of bandits was led by a Khampa called Taklha. Eventually he was apprehended and executed under the direction of a Ngari viceroy. Upon his death Taklha was transformed into a vengeful tsen spirit who would appear in wrathful form as a fiery blaze. It is believed that Taklha caused many problems and sickness in Ngari. Servants of the viceroy died and the viceroy himself became ill. On one occasion Taklha appeared before the viceroy and boasted to the leader that he would not be able to pass beyond Khampa La (in western Tsang?). Afterwards, on his way to Lhasa on official business, the viceroy died before reaching Khampa La. Officials in Ngari informed the government in Lhasa about what had happened; that the viceroy had been murdered by Taklha. By carrying out a divination officials in Lhasa were able to confirm that Taklha had indeed caused the death of the viceroy. Taklha was identified as a powerful tsen spirit and the Lhasa government ordered that he be made into a religious protector (chos-skyong) of Ngari and that a lhasol ritual be carried out in his honor. When the viceroys came to Takribuk they would bring along a spear that had been owned by Ganden Tshewang. It is said that when the Fifth Dalai Lama conducted a divination in order to select a general to subdue the western regions this spear fell at the feet of Ganden Tshewang.

August 17, 18, 2000: in the wilds of northwestern Tibet

We continued over the Dingleb La (Sdings-leb la; elevation 5100 m) without incident, having our lunch along the way. However, after traversing the pass (forms the boundary between Ruthok and Gegye counties) trouble set in. First, making a wrong turn, the truck and then the Landcruiser whilst trying to rescue it, became mired in mud. It took a couple hours of work in order to liberate them. We were not long on our way again when some mud on the road caused the drivers to quake in their seats. Ill-advisedly they tried to make a detour causing the truck to again get stuck in soft ground. By the time the truck was freed from its trap, it was time to make camp no closer to getting over a rough but well traveled piece of ground. I warned against the detour but my drivers do not have the experience or savvy to always make the right moves. More importantly, however, they take me where I need to go. That is most crucial. After the crew made some road improvements by lining the muddy track with stones our vehicles passed without further incident. This however was not the end of our route difficulties. Only a couple kilometers down valley the Landcrusier driver entered a bad section of the road too slowly and without the 4-wheel drive engaged, the result being that he again sunk into the mud. The truck also became stuck when it tried to pull the Landcruiser out of the quagmire. Many hours of difficult manual labor followed, as each wheel of the Landcruiser had to be jacked up inch by inch and stones placed under them, in order to raise the general level of the vehicle. This work is dirty and very slow going. Also, to improve traction, stones were dumped in the truck. This operation cost us the better part of the day and it was not until well after lunch that we were free to resume our travels.

Delays today and yesterday cost us 24 hours, a very significant period of time when you consider that there is less than one month left in the expedition including transit days back to Lhasa. It is frustrating loosing time to avoidable delays but once back on the road one is soon looking forward. There is still much to discover and little time to dwell on past failures. To keep morale good, I try not to criticize the drivers and so far my strategy has worked. The crew will only be fully paid when they return to Lhasa so they have every incentive to successfully complete the trip.