July 2012

John Vincent Bellezza

Flight of the Khyung

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung, the highest flying of all creatures and contraptions with wings! This month we will be examining some of Tibet’s most ancient deities, a real treat for your eyes. We will also take another look at the spectacular golden death mask recently discovered by Chinese archaeologists in Guge. First of all though, I would like to call your attention to a supplement that has been added to the bottom of the April 2012 newsletter. It features an extensive review of papers recently published in the Emerging Bon volume, which pertain to the archaeology of Khardong, Zhang Zhung’s putative capital. You can find it at:

http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/april-2012/

It may or may not be god

Tibetan religious art is world famous. Its colorful Buddhist and Bon wall murals, intricate paintings on cloth (thang-ka) and dazzling sculptures hardly need any introduction. Much of this religious art embodies the divine form, an amazingly rich spectrum of gods and goddesses and attending figures. As most readers know, there is a substantial body of Tibetan sculptural art in stone, wood and metal dating to the early historic period (650–1000 CE). Much has been written about the iconography, history and religious functions of this first Lamaist art.

Far less acknowledged, however, is the divine form prior to the early historic period. This is largely because relatively few artistic resources belonging to this period have been discovered and published.

When dealing with the interpretation of archaeological materials much hinges upon the definition. How does one go about deciding whether, say, a protohistoric copper alloy ibex sculpture depicts the biological form of the animal or a zoomorphic deity? Take rock art as well: it may not be evident which yak is the portrayal of flesh-and-blood quarry and which one may have been a magical emanation fit for oblations. There are many anthropomorphic figures in rock art compositions that appear to have had narrative or mytho-ritualistic significance. Nevertheless, there is no clear-cut method for discerning the portrayal of a god from a priest, or an ancestral hero from a latter-day warrior. The interpretative framework at our disposal is compromised by the potential for the human figure to have had composite identities, combining the mundane with the supernatural or the mythic past with the present day.

Without a historical record to rely on, it is very hard if not impossible to pronounce the original identity and function of archaic art in any verifiable and reproducible manner. This of course has not stopped students of rock art from weaving elaborate tales around subjects, often couching them in pseudoscientific language or embellishing their flights of fancy with complex methodology. Fortunately, this tendency in rock art studies towards tendentiousness has been steadily diminishing in recent years, at least among trained archaeologists. I hasten to add that in the scientific literature there are many fine interpretations about what rock art might have meant to its makers and how it may have been placed within the culture of users. The watchwords here are ‘might’ and ‘may’, auxiliary verbs that serve as the mortar holding together the conceptual blocks of any working hypothesis. The well-trained rock art researcher operates from a position of hesitancy and self-imposed limitation, while exploring every promising lead in order to tender avenues of meaning and relevance for carvings and paintings that cannot otherwise speak for themselves.

Divine riders of the unfettered

This newsletter is devoted to a genre of rock art in Upper Tibet that has one of the strongest claims for being representative of archaic divine figures (see the December 2011 newsletter too). The art in question is that in which anthropomorphic figures sit astride or stand on the backs of wild ungulates. I base my identification on the assumption that wild bull yaks and caprids are not likely to have ever been ridden by human beings. Moreover, none of these riders are associated with mundane activities such as hunting or combat. Tibetan literary and oral traditions are replete with art, rituals and myths in which deities are mounted on wild animals. This tradition carries on to the present day. A good many protective gods of Buddhism and Bon (chos-skyong, bon-skyong) sit on wild animals or have them within their retinues. Among these mounts and minions are bears, tigers, wolves, leopards, wild yaks, eagles, and hawks, etc.

Formal Lamaist divinities notwithstanding, many Tibetan folk deities use wild creatures as their conveyances. Among the popular deities commonly mounted on wild animals are protective spirits of males and females (pho-lha and mo-lha), warrior gods (dgra-lha, wer-ma, cang-shes), territorial deities (yul-lha, gzhi-bdag, sa-bdag), household, clan and genealogical deities (phugs-lha, rus-lha, mtshun), and the helping spirits of Tibetan mediums.

The use of wild animals as mounts and messengers can be traced back to Old Tibetan language literature written in the early historic period. These references to animals appear in non-Buddhist ritual texts and occur as part of either an individual tradition or complex of traditions, which is sometimes referred to as bon (not to be confused with its successor, the institutionalized Bon religion established in the late 10th century CE). In Old Tibetan funerary ritual literature, the three most common bearers of the deceased to the otherworld are equids, deer and vultures. Ibex, grouses and other birds and animals are also mentioned in texts that explicate eschatological concepts and mortuary practices (for more detailed information, see my forthcoming book, Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet).

Wild animals as something ridden in special circumstances in Tibet’s oldest body of literature may point the way to understanding analogous depictions in rock art. Yet, there are serious methodological challenges. For one thing, the functions of wild animal mounts in the prehistoric epoch and early historic period may have differed considerably. Cultures and religions change and evolve over time, and what looks superficially the same may in fact vary significantly in terms of underlying meaning and usage. The semantics and cultural applications of a single object or motif are potentially manifold.

There is another major hurdle as well. Even if the values and functions assigned wild animal mounts did not vary substantially between the literary and rock art records, how to correlate the two with any fidelity? One could be left comparing the proverbial apples and oranges. Yes, you do have a deceased woman’s soul mounted on a female yak in the Dunhuang manuscript Pt 1068 and yak riders in rock art in seemingly extraordinary conditions, but their signification potentially encompasses disparate aspects of the cultural spectrum. We simply cannot say for certain.

Upon outlining these admonitions, it is still the case that early historic period textual evidence is one of the best tools available for analytical purposes. It comprises the oldest unambiguous cultural record available, includes what appear to be similar cultural themes, and in some instances it is also set in the Upper Tibet. Thus, it is an ideal departure point for comprehending rock art even if the results are tentative and unverifiable. Another powerful analytical tool at our disposal is the Tibetan oral tradition but the methodological obstacles to harnessing it to ancient rock art interpretation are even greater. The biggest question surrounding any oral tradition is, ‘how old really is it’? All the same, let’s have some fun by pondering the intriguing possibilities!

Please note: dates assigned to rock art below are suggestive and not prescriptive. The direct dating rock art has yet to be carried out in Tibet. Many technical challenges to direct dating remain. See my print publications for more details.

Fig. 1. A rock art composition comprising yaks, swastikas, sun, and crescent, western Changthang, probably Iron Age (700–100 BCE).

This panel of equally re-patinated and styled carvings with its sacred symbolism appears to have had mytho-ritualistic significance. It is assuredly not a hunting scene, as is commonly found in Upper Tibet. There are simply no hunters among the subjects or in close proximity. The yaks shown are almost certainly the wild variety. In the rock art of the region there are very few domestic yaks or pastoral scenes, and which ones do exist date to the historic epoch. The two yaks are most probably bulls of the type known as sham-po (characterized by a long belly fringe and upright bushy tail). The upper yak is most curious, as it accommodates a rider. Yaks are indeed ridden in some parts of Tibet but usually this is the hornless variety. In Upper Tibet, however, yaks are not customarily ridden, at least in recent times. The symbols included in the composition are of the kinds that have cosmogonic, cosmological and mystic significance in Tibetan literature. This symbolism adds to the numinous overtones of the yak rider.

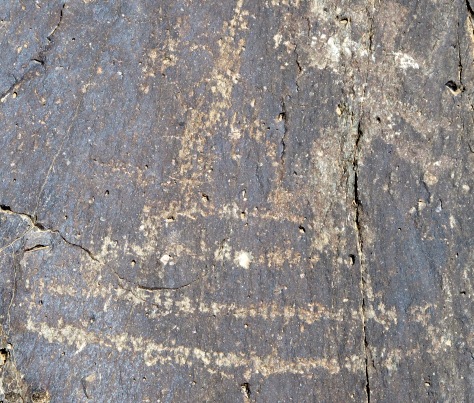

Fig. 2. A close-up of the yak rider. The long body, arm and round head of this figure are easily recognizable.

Suolang Wangdui writing about this petroglyph in Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings (p. 99), states, “On the back of the yak there is a man who seems to be a herdsman.” For reasons I have explained, this suggested identity by my esteemed elder colleague is unlikely. Rather, the yak rider appears to confirm the observation made by the Tibetologist Réne de Nebesky-Wojkowitz a half century ago: “A typical Tibetan animal frequently used as a mount by deities of truly Tibetan origin is the yak.” (p. 14, Oracles and Demons of Tibet).

Fig. 3. Another rider mounted on a bull yak, western Changthang, probably Iron Age. This anthropomorphic figure is styled quite differently from the previous one, but their identity seems closely aligned. They appear to be divine and/or heroic in nature. Suolang Wangdui published this composition and surrounding figures in Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings (p. 104).

These figures by virtue of being fully carved are silhouetted. The lower rider is highly stylized, arms outstretched, while the upper rider is more nebulous in appearance. Again, these ‘divinities’ are astride bull yaks. The yaks have horns with a double curve, barbed hair fringe and wedge-shaped tails, motifs that point to considerable antiquity.

The rider of the upper yak has an almost acrobatic aspect, as if he or she and the animal are flying. Perhaps the anthropomorphic figure is guiding the smaller yaks below as their divine escort. Until recently, hunters in the Changthang had special tutelary deities that were propitiated before and after a yak hunt. If parallels can be drawn, the anthropoid and its vehicle may have been carved and supplicated in order to ensure successful hunting operations.

The anthropomorphic figure in this composition is dressed in a long gown and stands on the back of a yak with outstretched arms. Unless there was some kind of contest in which men or women stood on the back of wild bull yaks, and this is highly implausible, this remarkable figure can only possess a supranatural identity. This rock art is somewhat comparable to an early historic period (?) thokcha (thog-lcags) depicting a figure standing on the back of an animal (see the cover of Arts of Asia, May-June 1998).

Fig. 7. A red ochre pictograph portraying a yak rider, eastern Changthang, protohistoric period or early historic period. The rider has a wedge-shaped head that appears to be surmounted by a pair of horns. This composition is examined in “Bon Rock Paintings at gNam mtsho: Glimpses of the Ancient Religion of Northern Tibet”, Rock Art Research, vol. 17 (1), pp. 35–55. Melbourne, 2000.

Fig. 8. Two anthropoids mounted on wild caprids, western Changthang, protohistoric period. This composition has been published in Suolang Wangdui’s (Bsod-nams dbang-’dus) Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings (p. 106), introduction by Li Yongxian and Huo Wei. Chengdu: Sichuan People’s Publishing House, 1994. Suolang Wangdui identifies the mounts as a goat and deer, but this is uncertain.

These extraordinary riders also convey a divine status. They could be the protectors of wild herds, the allies of hunters, clan deities, psychopomps, or other types of divinities associated with the Tibetan literary tradition that ride on the backs of wild animals. It is also possible that they represent an entirely different cultural theme, one that was lost to time. I am inclined, however, to see this last scenario as less plausible. That is because Tibetan culture exhibits a great deal of historical continuity as regards its basic themes and forms. What do you think? I am always eager to have the well-deliberated comments of readers.

Fig. 9. Red ochre anthropoid standing on the back of a wild ungulate or horse, eastern Changthang, early historic or vestigial period (1000–1250 CE).

This acrobatic rider is attired in a knee-length robe, and appears to be holding the reins while about to blow into a horn (?). Such a figure almost certainly was invested with a divine and/or heroic identity. This pictograph was published in Suolang Wangdui’s Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings (p. 148) and in my Divine Dyads: Ancient Civilization in Tibet (p. 197), Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 1997. It is also the subject of a fine painting created by the well-known Tibetan artist Losang Gyatso, who now resides in Colorado.

This unique figure has great poetic power. It holds an upright object in one hand, has a long tail, and perhaps horns or a hat on its head. I dare not speculate on its identity except to say that Tibetan rituals and narratives contain various accounts of theriomorphic deities, as well tales of adepts who turned themselves into animals to carry out special religious assignments.

Before there was the Buddhist stupa in Tibet

Fig. 11. The upper gilt or solid golden plate from the burial mask recently discovered in Guge by Chinese archaeologist Li Linhui. Photograph courtesy of Li Linhui.

For more information on this mask, see the October and November 2011 issues of this newsletter. In the current issue, I wish to highlight the three tired structures embossed on the mask. These appear to be facsimiles of the receptacles for the consciousness of the deceased used during the evocation rite (for more information, see my forthcoming book, Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet). This same type of tiered structure is also found in the rock art of western Tibet.

Fig. 12. In this example, a tiered shrine was carved over a chariot (for more on these chariots see the August 2010 and November 2011 newsletters). While the chariot carving probably dates to the late Bronze Age or Iron Age, the tiered shrine may be of the protohistoric period (like the embossed variety on the golden burial mask?).

Fig. 13. Another tired shrine in the rock art of Upper Tibet, protohistoric period. These likenesses of tiered shrines are also found in the monumental and artifactual records of the region. They are liable to have fulfilled a variety of functions, just like their more modern counterpart, the chorten. Which, if any, of the rock art representations served a funerary ritual function is unknown.

Next Month: The archaeology and cultural history of man-eaters, so watch it!