February 2012

John Vincent Bellezza

All aboard another Flight of the Khyung! Ancient art is our theme again this month, spurred on by the successes of recent expeditions. In the last two years, I have taken thousands of pictures of art from the cliffs and boulders of Upper Tibet. This rock art, located in what were once the Sumpa and Zhang Zhung kingdoms, conceals many mysteries and is a wonder to behold. I am hoping to begin compiling a comprehensive inventory of Upper Tibetan rock art this year. In the meantime, Flight of the Khyung will continue to bring you some of the most intriguing pictographs and petroglyphs of the Tibetan upland.

On January 8, I delivered a lecture to a full house at the Explorers Club headquarters in New York City. I am pleased to report that the talk appears to have been very well received. Being held in the Explorers Club, the lecture focused on the themes of exploration and adventure, which were woven into an overview of my research work.

Figures from foreign lands?

In the rock art record of Upper Tibet there are a number of compositions that stand out from the rest. This art is strange in form and execution – nothing like what the ancient Tibetans were usually painting and carving. These images contrast with the typical figurative and iconic representations, and with the religious, economic, social and political themes usually presented in Tibetan highland rock art. Exotic influences appear to be at play here. These atypical subjects may possibly be the handiwork of visitors to the uplands or they may have been created by indigenous artists documenting foreign peoples and customs. In this newsletter we’ll look at a few examples of pictographs that seem to intrude upon the artistic landscape.

Fig. 1. A trio of human figures attired in ankle length robes or caftans gathered at the waist and with relatively short sleeves. These figures and two nearby ones are unlike the depiction of any other anthropomorphic rock art in Upper Tibet. The red ochre figures have undergone considerable wear and ablation of the pigment (each figure is in the vicinity of 10 cm in height). Moreover, the composition is partially obscured by subsequent pigment applications and the running of pigment from adjacent pictographs. As for the age, I shall tentatively attribute it to the imperial period (circa 630–850 CE). Note the line drawing of a yak (horns visible on bottom left corner) superimposed on the composition at a later date.

The three figures are located in an eastern Changthang cave with other eccentric images that appear to have been inspired from afar. In one scene an individual leads two Bactrian camels, clearly documenting a Central Asian form of transportation (more on camels next month). Non-Tibetan ciphers or pictograms cover another rock panel in the same cave. Although it is only a hunch, I am persuaded to see our trio as of foreign origin as well. My two main reasons for this hypothesis are as follows:

1) The shorter sleeves of the garments and that they appear to have been made from a textile (note the stripes on the robe on the right). Tibetans certainly have cloth garments in this general style but their depiction in the Changthang seems idiosyncratic.

2) The manner in which the middle figure appears to sport either hair coiffed in one high bunch or a tall narrow headdress positioned on the rear of the head (yes, I think these are probably representations of male figures).

To initiate a debate, I shall put forward that this composition may depict Sogdian traders, who visited the locale (an important pilgrimage site) en route to or from Lhasa. In any case, they belong to a privileged social class or so I would think. From what is visible in the pictograph, I know this attribution is a big stretch but one must begin somewhere. If you the readers have any ideas as to the identity of these figures or comments on any other rock art featured in the newsletters, please do not hesitate to let me know. I shall highly value any reasoned input.

Fig. 2. A close-up view of the figure on the right. He wears a striped robe, perhaps depicting a silk textile, and what appears to be a big turban or hat on the head (which may be depicted in profile). Although now highly obscured, it appears that this figure was painted with relatively detailed facial features.

Fig. 3. The middle figure with what appears to be a coiffure possibly of Central Asian persuasion. Sogdian and Manichaean art immediately comes to mind here, but there is nothing I can directly point to that says, ‘eureka’! This figure may be depicted with its head in profile.

Fig. 4. One of two atypical figures located near the trio of figures discussed above. This individual dons what appears to be a tall turban. His facial features are still visible but they are not sufficiently detailed to make any pronouncement about their ethnic or racial nature. Next to this figure is a more ambiguously painted one holding a sword upright. Beside it is another sword.

Pillars marking the ages

In 1999, I documented a row of eight pillars in northwestern Tibet. Six of these standing stones are integrated into a corral (still used on a seasonal basis). These pillars have proven convenient structural supports for the west wall of this corral. During the first visit, I could only shoot a few pictures, as film in the field was at a real premium. In 2011, however, I could take digital photos to my satisfaction.

Fig. 5. Like the other four specimens at the site, these four pillars or stelae were hewn from igneous rocks. The two pillars on the right side of the photo are made from white granite and are 1.4 m and 1.6 m in height (not including the portions firmly anchored in the ground). I am not certain how far away the quarry for these pillars was located – that’s something for further research. The third pillar from the right was engraved with several mani mantras and traces of other short inscriptions and designs that are now almost effaced.

Fig. 6. What I did not appreciate in 1999 is that inside the corral there are slabs of stone embedded in the ground, which run parallel to the line of pillars. These stones may have formed the west wall of an enclosure in which the pillars were erected. If this assessment is correct, this site is one of the most common types of funerary ritual monuments in Upper Tibet: walled-in pillars. The wide spacing of the pillars may suggest that originally there was more than one enclosure. In any event, it is not unusual to see stones from ancient monuments recycled for use in pastoral structures.

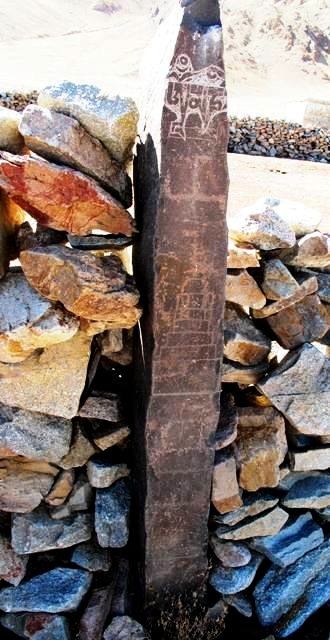

Fig. 7. On the top of the east face of this pillar (1.5 m in height) are the first three letters of the mani mantra below which a primitive or folk-style swastika (arms are much shorter than the central cross) was carved. In a more inferior position are two engraved chortens. The incomplete mani inscription was chiseled using an entirely different technique and exhibits much less wear and re-patination than the other carvings on the pillar. This physical evidence clearly indicates that the inscription was made more recently. Lone chortens and swastikas are found on walled-in pillars from other sites in the region as well. Nevertheless, the carving of such stelae was not common (for other examples, see Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: www.thlib.org/bellezza).

Fig. 8. A close-up of the upper chorten on the pillar reveals more complexity. It is now composed of five sharply incised graduated tiers, which sit on a tall plinth and are topped by a small semi-circular bumpa. The bumpa appears to be surmounted by a segmented spire, which is more heavily patinated and carved in a different manner (using a pecking technique). In fact, this spire, and the bumpa and two of the tiers below it appear to constitute an older and cruder petroglyph. The remainder of the current one was almost certainly added on later using more sophisticated cutting tools. The relative degree of physical wear indicates that possibly centuries separate the creation and recreation of this petroglyph. On the basis of the style and carving technique, the earlier part of the upper chorten, lower chorten (with its three crude tiers and bumpa) and swastika can probably be attributed to the early historic period (650–1000 CE). The more recent portion of the upper chorten dates to the vestigial period (1000–1250 CE) or perhaps even later. The clockwise orientation of the swastika may possibly indicate a Buddhist identity for it and the other carvings as well.

Fig. 9. This pillar is situated south of the corral and is 1.5 meters in height. It was engraved with two chortens and a much more recent mani mantra inscription sandwiched between them. The difference in the wear and patination between the inscription and chortens is dramatic. The upper chorten lacks a clearly defined spire. The two chortens (the lower specimen is barely discernible) date either to the early historic period or vestigial period.

Fig. 10. The top of this pillar was broken off and it now stands only 60 cm in height. An archaic style chorten (25 cm high) was deeply cut into its surface using an old engraving technique. This style of chorten with its vertically segmented base, small round bumpa, very prominent harmika (T-shaped structure at top), and absence of a spire can almost certainly be attributed to the early historic period.

Fig. 11. This chorten carving with its long and narrow form, small round bumpa and horn-like finial can also be ascribed to the early historic period. This periodization is supported by the carving technique used as well. A small archaic chorten of three tiers with a rounded upper section was also carved near the top of the pillar. I failed to document these two rock art chortens during my 1999 survey of the site. Unlike other petroglyphs at this location, these examples were placed on the west side of a pillar.

My survey of many dozens of locations with pillars standing inside quadrate stone fences shows that they were erected unadorned. That the petroglyphs made on the funerary pillars we have examined are not original features, but rather later modifications, seems to furnish us with valuable clues as to when the original functions of the standing stones began to change. The same basic observation can be made for the few stelae at other walled-in pillar sites adventitiously carved with chortens and swastikas. From the stylistic indications we have examined above, this only began to occur in the early historic period.

That the pillars had a preexisting sacral or ritual status is strongly suggested by the motifs selected for carving: chortens and swastikas. This might be expected of monuments raised for the dead. The addition of this rock art seems to tell us that religious traditions were undergoing change in the early historic period, and that the funerary pillars needed to be brought into the new religious order. Buddhism began making a large impact in Tibet in the imperial period, the upper regions of the Plateau being no exception. Of course it was in that period that the Upper Tibetan kingdoms of Sumpa and Zhang Zhung were absorbed into the expanding Tibetan empire. The chortens carved on pillars appear to be emblematic of this changed political and religious landscape. Unadorned pillars of an earlier age being altered in such a way signal that a certain cultural obsolescence regarding them had set in as early as the 7th century CE. This seems to imply that the walled-in pillar monuments were no longer being built by that time.

In earlier publications, in the absence of any direct dating, I hold out the prospect that wall-in pillars may have been constructed as late as the 10th century CE, as an anachronistic funerary tradition. I now think that such a late date is unlikely. Given the rock art evidence, my current position is that the walled-in pillars were probably not raised after the close of the protohistoric period (100 BCE–650 CE). The same line of thinking can be extended to the concourses of pillars appended to temple-tombs: we can be fairly confident that they were not being built after the protohistoric period.

A new online archaeological inventory

It has only recently come to my attention that a broad inventory of archaeological monuments in the Mongolian Altai has been published online by the University of Oregon. This project to document archaeological sites on the surface was carried out by Esther Jacobson-Tepfer and her team. Those interested in Tibetan archaeology will find it rewarding to compare the ancient pillar monuments and other funerary structures of Upper Tibet with those of the Mongolian Altai. There are a number of general morphological correspondences that are worth further consideration. Professor Jacobson-Tepfer’s excellent work can be found at: http://oregondigital.org/digcol/maic/

Flying high: Horse racing in Upper Tibet

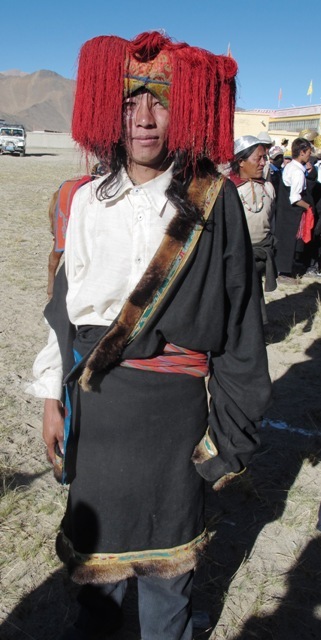

Just for fun let’s finish this issue with a few pictures of an autumn horse racing festival that took place in Ruthok, in 2011. I snapped these shots quickly between other assignments.

Fig. 12

Fig. 13

Fig. 14